History

World War II amputee veteran reflects on D-Day 75th anniversary

On June 6, 1944, Toronto’s Allan Bacon was one of thousands of Canadians to arrive by boat on the shores of Juno Beach in Normandy, France. As this year marks the 75th anniversary of D-Day, 99-year-old Bacon is reflecting on that pivotal event.

Bacon enlisted with the Royal Regiment of Canada in 1940 and was later transferred to the Canadian Scottish Regiment. When his tour of duty took him to Normandy, his role was in the mortar platoon. “That was because I had difficulty opening one eye at a time, which was required to operate a rifle,” he recalls.

On June 17, 1944, Bacon was based in a barn, anticipating an attack that never came. He went into a nearby shed to disarm the grenades when one exploded, resulting in the loss of his right arm.

When Bacon realized he’d lost his arm, his first thought was, “This will break my mother’s heart.” Bacon recovered at a hospital in England where he learned to use his left arm through exercises like washing windows.

Second World War veteran Allan Bacon in 1941 (left), and today (right), pictured at the Sunnybrook Veterans Centre, in Toronto.

On returning to Canada, he became a member of The War Amps, an Association started by amputee veterans returning from the First World War to help each other adapt to their new reality. Today, Bacon continues to be active with The War Amps Toronto Branch

Bacon’s daughter, Deborah Sliwinski, says, “In our family, we see my father as a hero. He talks about how losing his arm was the best thing that ever happened to him because it gave him the courage to try new things.”

When asked what he thinks of being called a hero, Bacon says that he didn’t do anything out of the ordinary, adding that at the time, men and women enlisted with the goal of protecting the country and he wanted to do the same.

Through the years, he along with his fellow War Amps members, have made it a goal to remember and commemorate their fallen comrades, and to educate youth about the horrors of war. “In Normandy, many Canadians died or suffered wounds that they had to carry for the rest of their lives,” says Bacon. “On anniversaries like D-Day, it’s important that we never forget.”

Community

New Documentary “Cooking with Hot Stones” Explores History of Fort Assiniboine, Alberta

February 14, 2025 – Alberta, Canada – A compelling new documentary, Cooking with Hot Stones: 200th Anniversary of Fort Assiniboine, is set to air on Wild TV, RFD TV Canada, Cowboy Channel Canada, and you can click here to stream for FREE on Wild TV’s streaming service, Wild TV+. This engaging one-hour feature will take viewers on a journey through time, exploring Fort Assiniboine’s rich history from 1823 to 2023.

Fort Assiniboine is a significant landmark in Alberta, playing a crucial role in Indigenous history, the fur trade, and the western expansion of Canada. This documentary captures the spirit of the region, illustrating how it has evolved over two centuries and how it continues to shape the cultural fabric of the province today.

Wild TV will make the documentary free to stream on Wild TV+ on February 14th so that it can be easily accessed in classrooms and other educational settings throughout the region, ensuring the historical significance of Fort Assiniboine reaches a wider audience.

Produced by Western Directives Inc., Cooking with Hot Stones: 200th Anniversary of Fort Assiniboine brings historical moments to life with vivid storytelling, expert interviews, and breathtaking cinematography.

“We are very excited to partner with Wild TV as part of our one hour documentary production. Based in Alberta, we respect the hard work and quality programming that Wild TV brings to a national audience. With the broadcast opportunity, Wild TV gives our production the ability to entertain and educate Canadians across the country on multiple platforms,” said Tim McKort, Producer at Western Directives.

Scott Stirling, Vice President of Wild TV, also expressed enthusiasm for the project: “At Wild TV, we are passionate about telling Canadian stories that resonate with our audiences. This documentary not only highlights a crucial piece of our nation’s history but also celebrates the resilience and contributions of Indigenous peoples, traders, and settlers who shaped the land we call home today. We are proud to bring Cooking with Hot Stones: 200th Anniversary of Fort Assiniboine to our viewers across Canada.”

Airtimes for Wild TV can be found here.

For airtimes on RFD TV Canada, click here.

For airtimes on Cowboy Channel Canada, visit CCC’s schedule.

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Hungarian Revolution of 1956: A Valiant Effort to Overthrow Communist Rule

Civilians wave Hungary’s national flag from a captured Soviet tank in Budapest’s main square during the anti-communist uprising of October 1956. AP Photo

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Gerry Bowler

For a time, Moscow seemed willing to accept change in Hungary, but when Nagy announced that his country would leave the Warsaw Pact and become neutral in the Cold War, that was a bridge too far for Khrushchev.

After World War II ended in the summer of 1945, the Soviet Red Army found itself to be in possession of Eastern Europe. In the next few years, the USSR extinguished the young democracies in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, while imposing Stalinist governments on autocracies such as Bulgaria and Hungary. With Marxist regimes taking over in eastern Germany, and Albania and Yugoslavia as well, Winston Churchill spoke truly when he said that “from Stettin the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent.”

In many of these countries, there was considerable resentment over the Russian occupation. In the Baltic republics, Romania, Croatia, Belarus, Poland, and Ukraine, doomed anti-Soviet guerilla movements with names like the “Forest Brothers,” the “Cursed Soldiers,” or “Crusaders,” fought underground wars that\ lasted for years. In June 1953 in East Berlin, workers rose up in protests against their communist masters, sparking a short-lived rebellion that spread to hundreds of towns before being crushed by Russian tanks. The most serious of these insurrections was the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. By 1956, there were stirrings of discontent in the Hungarian People’s Republic. Under the state control of industry, forced agricultural collectivization, and the shipping of produce to the Soviet Union, the economy was in bad shape. The supply of consumer goods was low and standards of living were dropping. Secret police surveillance of the population was harsh, while many Hungarians resented the suppression of religion and the mandatory instruction of the Russian language in schools. As news leaked out about Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin in the so-called “Secret Speech,” hopes grew that reform of the communist system was possible.

Marxist intellectuals began to form study circles to discuss a new path for Hungarian socialism, but their cautious proposals were suddenly overtaken by demands for change by young people. On Oct. 22, 1956, students at the Technical University of Budapest drew up a list of demands for change known as the “Sixteen Points.” They included free elections, a withdrawal of Soviet troops, free speech, and an improvement in economic conditions.

On the afternoon of the next day, these points were read out to a crowd of 20,000 who had gathered at the statue of a leader of the Hungarian rebellion of 1848. By 6 p.m., when the students marched on the Parliament Building, the crowd had grown to around 200,000 people. This alarmed the government, and later that evening Communist Party leader Erno Gero took to the radio to condemn the Sixteen Points. In reaction, mobs tore down an enormous statue of Stalin.

People surround the decapitated head of a huge statue of Josef Stalin in Budapest during the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. Daniel Sego (second L), who cut off the head, is spitting on the statue. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

On the night of Oct. 23, crowds gathered outside the state broadcaster, Radio Budapest, to demand that the Sixteen Points be sent out over the air. The secret police fired on the protesters, killing a number of them. This enraged the demonstrators who set fire to police cars and seized arms from military depots. Army units ordered to support the secret police rebelled and joined the protest. The government floundered; on the one hand, they called Soviet tanks into Budapest; on the other hand, they appointed Imre Nagy, seen as a popular reformer, as prime minister.

As barricades were being erected by protesters and shots were being exchanged with secret police units, Nagy was negotiating with the Soviets who agreed that they would withdraw their tanks from the capital. Over the next few days, the rebellion spread; factories were seized, Communist Party newspapers and headquarters were attacked, and known communists and secret police agents were murdered. The new prime minister released political prisoners and promised the establishment of democracy, with freedom of speech and religion.

For a time, Moscow seemed willing to accept change in Hungary, but when Nagy announced that his country would leave the Warsaw Pact and become neutral in the Cold War, that was a bridge too far for Khrushchev. Fearing the collapse of the entire Soviet bloc, he made plans for an invasion of Hungary. By Nov. 3, the Red Army had surrounded Budapest, and the next day heavy fighting erupted as armoured columns entered the city. Some units of the Hungarian army fought back, joined by thousands of civilians, but the end was predictable. After a week of battles, with over 20,000 dead and wounded, resistance crumbled. A new Soviet-approved government under János Kádár purged the army and Communist Party, arrested thousands, and executed rebel leaders including Nagy.

Hundreds of thousands of refugees fled, many of them settling in Canada and the United States. World condemnation of the USSR was strong; critics of the Soviets included many communists in the West who resigned their party membership. Not until the collapse of the Soviet hold on Eastern Europe in 1989 did Hungarians get another taste of freedom.

Published in the Epoch Times.

Gerry Bowler, historian, is a Senior Fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

-

2025 Federal Election18 hours ago

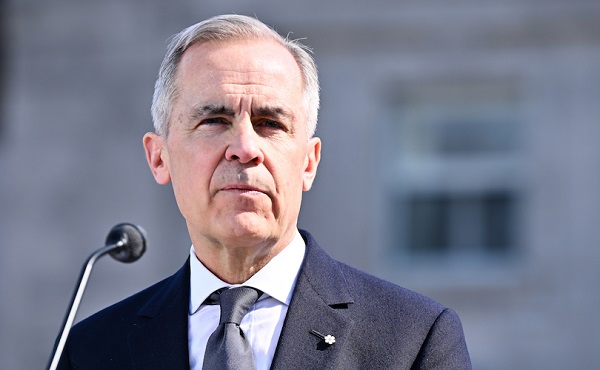

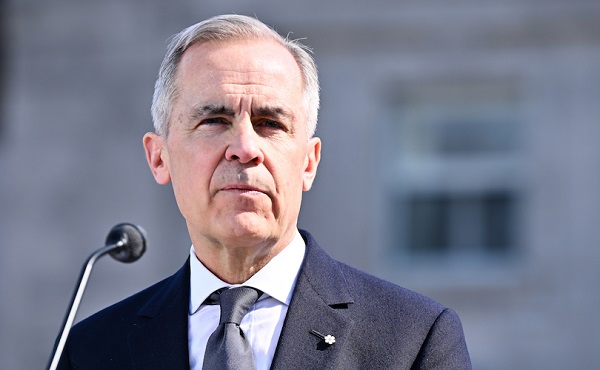

2025 Federal Election18 hours agoMark Carney refuses to clarify 2022 remarks accusing the Freedom Convoy of ‘sedition’

-

2025 Federal Election22 hours ago

2025 Federal Election22 hours agoPoilievre To Create ‘Canada First’ National Energy Corridor

-

Bruce Dowbiggin20 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin20 hours agoAre the Jays Signing Or Declining? Only Vladdy & Bo Know For Sure

-

2025 Federal Election21 hours ago

2025 Federal Election21 hours agoFixing Canada’s immigration system should be next government’s top priority

-

Daily Caller19 hours ago

Daily Caller19 hours agoBiden Administration Was Secretly More Involved In Ukraine Than It Let On, Investigation Reveals

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCanada Continues to Miss LNG Opportunities: Why the World Needs Our LNG – and We’re Not Ready

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoSelective reporting on measles outbreaks is a globalist smear campaign against Trump administration.

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoMark Carney is trying to market globalism as a ‘Canadian value.’ Will it work?