Bjorn Lomborg

World chaos looms thanks to elites’ policies

By Bjorn Lomborg InsideSources.com

The disconnect between the global elite and the real world is growing daily. Most people are worn down by the pandemic, food and energy price hikes and general inflation, and they worry about a recession. Yet, the chattering classes are jetting into conferences in Davos or Aspen to declare that our biggest, immediate threats are climate change, environmental disasters and biodiversity loss.

This ignores most of our urgent crises. Almost a billion people are at risk of starvation this year, exacerbated by climate-concerned opposition to fertilizers made with fossil fuels. More than a billion schoolchildren have missed an average of nine months of learning because of lockdowns, which will cost their generation $1.6 trillion every year by 2040. Millions in the rich world will unnecessarily die of undiagnosed cancer and heart disease ignored during COVID, while millions more in the poor world will die unnecessarily of malaria and tuberculosis, just like they always do.

If you’re a wealthy, climate-concerned jet setter with private health insurance and a safe job, you don’t need to worry about malaria, recession, waiting in line for cancer tests or your children falling behind when schools close again. Nor are these the issues that will get you attention or airtime.

Solving the real world’s big problems is messy, and progress is slow and unspectacular. It is far more exhilarating to make grand promises to save the entire world by going net-zero or abandoning synthetic fertilizers.

Climate change is a real, man-made problem that deserves attention. It is also wildly overblown in the media, with every weather “event” turned into a televisual catastrophe. Last year, newspapers overflowed with stories of devastating hurricanes. Yet, 2021 had the fewest hurricanes globally since satellites started consistently monitoring the world in 1980. Hundreds of deaths from heat waves top the news for days, as in Europe just now, even though the data show everywhere many more people — 4.5 million globally — die of cold temperatures, often because of a lack of heating exacerbated by high energy prices.

The costs of the climate and environmental policies pushed at establishment talkfests are quickly becoming unbearable. For decades, we have been told that ending fossil fuels is cost-free or even beneficial. Now, we are seeing the immense economic and security costs of such untethered promises. Early pushback came in France with the “yellow vest” protests.

The Netherlands has been roiled by protests since the government introduced policies that would decimate the agricultural industry in the name of the environment. The policies threaten the production of the world’s second-largest food exporter right when global hunger is rising, yet the government cannot change course because environmentalists have taken legal action to lock in the lopsided policies.

It is even worse in Sri Lanka. Egged on by elite campaigners and the World Economic Forum to go organic, the government banned synthetic fertilizers in April 2021. Predictably, food production collapsed, and the currency defaulted. Large-scale protests from hungry and dissatisfied citizens who overran the presidential palace have now forced the resignation of the government.

Solving many of these problems is not rocket science. The rich should stop making food more expensive by insisting on organics. They should stop making energy more expensive by dictating intermittent renewables. Instead, we should increase research and development into better seeds to deliver more food with a lower environmental footprint. We should drive green-energy breakthroughs that could make drastic carbon-dioxide reductions cheap and feasible. And we should include the many other urgent crises that have simple and effective solutions — for instance, for tuberculosis and for securing much better learning in schools across the world with computer-assisted teaching at the right level.

Unfortunately, the elite seems to double down on climate and environment, and the Netherlands and Sri Lanka are just warnings of what will come. Net-zero will be the costliest policy that the world has ever embarked upon. The price tag just for paying for renewable assets and infrastructure alone will be more than $5 trillion every year for the next three decades, according to McKinsey &Co., a global management consulting firm. This equates to more than one-third of the global tax intake. For the United States, one study shows that getting 80 percent of the way to President Joe Biden’s climate promises by midcentury would cost each American more than $5,000 every year. Going all the way would likely more than double that cost.

Every year the European Union has to pay $68.5 billion in subsidies to support its renewables. But if the bloc persists — or is forced by courts — with its even stauncher net-zero promises, this price tag could explode to more than $1 trillion annually.

As in the Netherlands, governments will find themselves caught between environmentalists who use legal action to hold them to virtue-signaling vows and working families who cannot cope with rising prices.

The wild increases in energy prices in Europe, although partly caused by poorly designed climate policies, are mostly because of Russia’s indefensible war with Ukraine. But the energy cost could increase more every year for everyone if politicians double down on net-zero.

Even under today’s policies, European Union vice president and longtime climate action advocate Frans Timmermans acknowledges that many millions of Europeans might be unable to heat their homes this winter. This, he concludes, could lead to “very, very strong conflict and strife.”

He’s right. When people are cold, hungry and broke, they rebel. If the elite continues pushing incredibly expensive policies that are disconnected from the urgent challenges facing most people, we need to brace for much more global chaos.

Bjorn Lomborg

Net zero’s cost-benefit ratio is CRAZY high

From the Fraser Institute

The best academic estimates show that over the century, policies to achieve net zero would cost every person on Earth the equivalent of more than CAD $4,000 every year. Of course, most people in poor countries cannot afford anywhere near this. If the cost falls solely on the rich world, the price-tag adds up to almost $30,000 (CAD) per person, per year, over the century.

Canada has made a legal commitment to achieve “net zero” carbon emissions by 2050. Back in 2015, then-Prime Minister Trudeau promised that climate action will “create jobs and economic growth” and the federal government insists it will create a “strong economy.” The truth is that the net zero policy generates vast costs and very little benefit—and Canada would be better off changing direction.

Achieving net zero carbon emissions is far more daunting than politicians have ever admitted. Canada is nowhere near on track. Annual Canadian CO₂ emissions have increased 20 per cent since 1990. In the time that Trudeau was prime minister, fossil fuel energy supply actually increased over 11 per cent. Similarly, the share of fossil fuels in Canada’s total energy supply (not just electricity) increased from 75 per cent in 2015 to 77 per cent in 2023.

Over the same period, the switch from coal to gas, and a tiny 0.4 percentage point increase in the energy from solar and wind, has reduced annual CO₂ emissions by less than three per cent. On that trend, getting to zero won’t take 25 years as the Liberal government promised, but more than 160 years. One study shows that the government’s current plan which won’t even reach net-zero will cost Canada a quarter of a million jobs, seven per cent lower GDP and wages on average $8,000 lower.

Globally, achieving net-zero will be even harder. Remember, Canada makes up about 1.5 per cent of global CO₂ emissions, and while Canada is already rich with plenty of energy, the world’s poor want much more energy.

In order to achieve global net-zero by 2050, by 2030 we would already need to achieve the equivalent of removing the combined emissions of China and the United States — every year. This is in the realm of science fiction.

The painful Covid lockdowns of 2020 only reduced global emissions by about six per cent. To achieve net zero, the UN points out that we would need to have doubled those reductions in 2021, tripled them in 2022, quadrupled them in 2023, and so on. This year they would need to be sextupled, and by 2030 increased 11-fold. So far, the world hasn’t even managed to start reducing global carbon emissions, which last year hit a new record.

Data from both the International Energy Agency and the US Energy Information Administration give added cause for skepticism. Both organizations foresee the world getting more energy from renewables: an increase from today’s 16 per cent to between one-quarter to one-third of all primary energy by 2050. But that is far from a transition. On an optimistically linear trend, this means we’re a century or two away from achieving 100 percent renewables.

Politicians like to blithely suggest the shift away from fossil fuels isn’t unprecedented, because in the past we transitioned from wood to coal, from coal to oil, and from oil to gas. The truth is, humanity hasn’t made a real energy transition even once. Coal didn’t replace wood but mostly added to global energy, just like oil and gas have added further additional energy. As in the past, solar and wind are now mostly adding to our global energy output, rather than replacing fossil fuels.

Indeed, it’s worth remembering that even after two centuries, humanity’s transition away from wood is not over. More than two billion mostly poor people still depend on wood for cooking and heating, and it still provides about 5 per cent of global energy.

Like Canada, the world remains fossil fuel-based, as it delivers more than four-fifths of energy. Over the last half century, our dependence has declined only slightly from 87 per cent to 82 per cent, but in absolute terms we have increased our fossil fuel use by more than 150 per cent. On the trajectory since 1971, we will reach zero fossil fuel use some nine centuries from now, and even the fastest period of recent decline from 2014 would see us taking over three centuries.

Global warming will create more problems than benefits, so achieving net-zero would see real benefits. Over the century, the average person would experience benefits worth $700 (CAD) each year.

But net zero policies will be much more expensive. The best academic estimates show that over the century, policies to achieve net zero would cost every person on Earth the equivalent of more than CAD $4,000 every year. Of course, most people in poor countries cannot afford anywhere near this. If the cost falls solely on the rich world, the price-tag adds up to almost $30,000 (CAD) per person, per year, over the century.

Every year over the 21st century, costs would vastly outweigh benefits, and global costs would exceed benefits by over CAD 32 trillion each year.

We would see much higher transport costs, higher electricity costs, higher heating and cooling costs and — as businesses would also have to pay for all this — drastic increases in the price of food and all other necessities. Just one example: net-zero targets would likely increase gas costs some two-to-four times even by 2030, costing consumers up to $US52.6 trillion. All that makes it a policy that just doesn’t make sense—for Canada and for the world.

Bjorn Lomborg

Global Warming Policies Hurt the Poor

From the Fraser Institute

Had prices been kept at the same level, an average family of four would be spending £1,882 on electricity. Instead, that family now pays £5,425 per year. The average UK person now consumes just over 10 kWh per day—a low point in consumption not seen since the 1960s.

We are often told by climate campaigners that climate change is especially pernicious because its effects over coming decades will disproportionately affect the poorest people in Canada and the world. Unfortunately, they miss that climate policies are directly hurting the poor right now.

More energy leads to better, healthier, longer lives. Less energy means fewer opportunities. Climate policies demand we pay more for less reliable energy. The impact is greater if you’re poorer: the wealthy might grumble about higher costs but can generally absorb them; the poor are forced to cut back.

For evidence, look to the United Kingdom which has led the world on stiff climate policies and net zero promises for some two decades, sustained by successive governments: its inflation-adjusted electricity price, weighted across households and industry, has tripled from 2003 to 2023, mostly because of climate policies. The total, annual UK electricity bill is now $CAD160 billion, which is $CAD105 billion more than if prices in real terms had stayed unchanged since 2003. This unnecessary increase is so costly that it is twice the entire cost that the UK spends on elementary education. Had prices been kept at the same level, an average family of four would be spending £1,882 on electricity. Instead, that family now pays £5,425 per year.

Over that time, the richest one per cent absorbed the costs and even managed to increase their consumption. But the poorest fifth of UK households saw their electricity consumption decline by a massive one-third.

The effects of climate policies mean the UK can afford less power. The average UK person now consumes just over 10 kWh per day—a low point in consumption not seen since the 1960s. While global individual electricity consumption is steadily increasing, the energy available to an average Brit is sharply decreasing.

Climate policies hurt the poor even in energy-abundant countries like Canada and the United States. Universally, poor people in well-off countries use much more of their limited budgets paying for electricity and heating. US low-income consumers spend three-times more on electricity as a percentage of their total spending than high-income consumers. It’s easy to understand why the elites have no problem supporting electricity or gas price hikes—they can easily afford them.

As mentioned in the article on cold and heat deaths, high energy prices literally kill people—and this is especially true for the poor. Cold homes are one of the leading causes of deaths in winter through strokes, heart attacks, and respiratory diseases. Researchers looked at the natural experiment that happened in the United States around 2010, when fracking delivered a dramatic reduction in costs of natural gas. The massive increase in availability of natural gas drove down the price of heating. The scientists concluded that every single winter, lower energy prices from fracking save about 12,500 Americans from dying. To put this another way, all else being equal, a reversal and hike in energy prices would kill an additional 12,500 people each year.

As bleak as things are for the poor in rich countries, virtue-signaling climate policy has even farther-reaching impacts on the developing world, where people desperately need more access to the cheap and plentiful energy that previously allowed rich nations to develop. In the poor half of the world, more than two billion people have to cook and keep warm with polluting fuels such as dung and wood. This means their indoor air is so polluted it is equivalent to smoking two packs of cigarettes a day—causing millions of deaths each year.

In Africa, electricity is so scarce that the total electricity available per person is much less than what a single refrigerator in the rich world uses. This hampers industrialization, growth, and opportunity. Case in point: The rich world on average has 650 tractors per 50km2, while the impoverished parts of Africa have just one.

But rich countries like Canada—through restrictions on bilateral aid and contributions to global bodies like the World Bank—refuse to fund anything remotely fossil fuel-related. More and more development and aid money is being diverted to climate change, away from the world’s more pressing challenges.

Canada still gets more than three-quarters of its energy (not just electricity) from fossil fuels. Yet, it blocks poor countries from achieving more energy access, with the naïve suggestion that the poor “skip” to intermittent solar and wind with an unreliability that the rich world does not accept to fulfil its own, much bigger needs.

A large 2021 survey of leaders in low- and middle-income countries shows education, employment, peace and health are at the top of their development priorities, with climate coming 12th out of 16 issues. But wealthy countries refuse to pay attention to what poor countries need, in the name of climate change.

The blinkered pursuit of climate goals blinds politicians in rich countries like Canada to the impacts on the poor, both here and across the world in developing nations. Climate policies that cause higher energy costs and push people toward unreliable energy sources disproportionately burden those least able to bear them.

-

2025 Federal Election11 hours ago

2025 Federal Election11 hours agoThe Federal Brief That Should Sink Carney

-

2025 Federal Election13 hours ago

2025 Federal Election13 hours agoHow Canada’s Mainstream Media Lost the Public Trust

-

2025 Federal Election16 hours ago

2025 Federal Election16 hours agoOttawa Confirms China interfering with 2025 federal election: Beijing Seeks to Block Joe Tay’s Election

-

2025 Federal Election15 hours ago

2025 Federal Election15 hours agoReal Homes vs. Modular Shoeboxes: The Housing Battle Between Poilievre and Carney

-

John Stossel12 hours ago

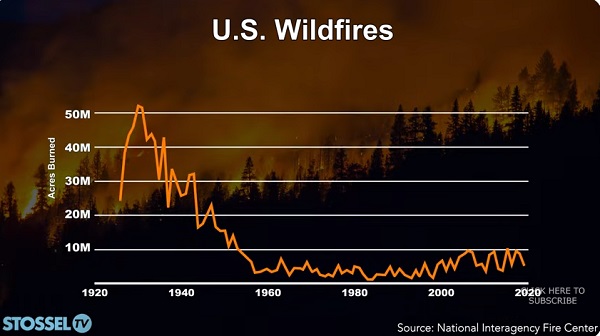

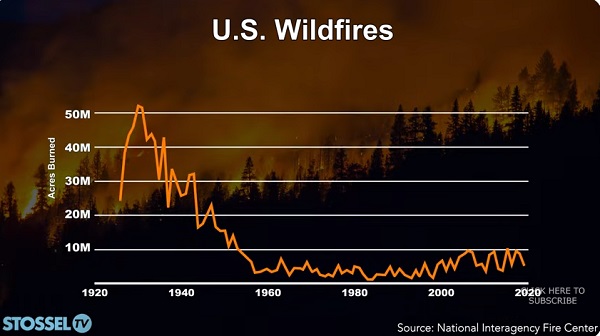

John Stossel12 hours agoClimate Change Myths Part 2: Wildfires, Drought, Rising Sea Level, and Coral Reefs

-

COVID-1914 hours ago

COVID-1914 hours agoNearly Half of “COVID-19 Deaths” Were Not Due to COVID-19 – Scientific Reports Journal

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoPoilievre Campaigning To Build A Canadian Economic Fortress

-

Entertainment2 days ago

Entertainment2 days agoPedro Pascal launches attack on J.K. Rowling over biological sex views