The announcement marks the first time SITE has publicly confirmed that China is directly seeking to block the election of a particular candidate during the 2025 federal election—an election already shadowed by growing concern over Chinese interference through cyber operations and diaspora political networks.

One week before Canadians head to the polls, Ottawa has confirmed an escalation in China’s election interference efforts, identifying Conservative candidate Joseph Tay as the target of a widespread and highly coordinated ongoing transnational repression campaign tied to the People’s Republic of China.

The SITE Task Force—Canada’s agency monitoring information threats during the election—formally disclosed today that Tay, the Conservative Party candidate for Don Valley North, is the victim of inauthentic online amplification, digital suppression, and reputational targeting orchestrated by networks aligned with Beijing’s foreign influence operations.

The announcement marks the first time SITE has publicly confirmed that China is directly seeking to block the election of a particular candidate during the 2025 federal election—an election already shadowed by growing concern over Chinese interference through cyber operations and diaspora political networks.

“This is not about a single post going viral,” SITE warned. “It is a series of deliberate and persistent activity across multiple platforms—a coordinated attempt to distort visibility, suppress legitimate discourse, and shape the information environment for Chinese-speaking voters in Canada.”

SITE said the most recent coordinated activity occurred in late March, when a Facebook post appeared denigrating Tay’s candidacy. “Posts like this one appeared en masse on March 24 and 25 and appear to be timed for the Conservative Party’s announcement that Tay would run in Don Valley North,” SITE stated in briefing materials.

One post, circulated widely in Chinese-language spaces, featured an image that read: “Wanted for national security reasons, Joe Tay looks to run for a seat in the Canadian Parliament; a successful bid would be a disaster. Is Canada about to become a fugitive’s paradise?”

Significantly, according to The Bureau’s analysis, the post’s message resembles earlier remarks made by then-Liberal MP Paul Chiang to a small group of Chinese journalists in Toronto in January—comments made shortly after Tay’s inclusion on a Hong Kong bounty list was first publicized.

Chiang reportedly told the journalists that Tay’s election would raise significant concern due to the bounty he faced, before suggesting that Tay could be turned over to the Chinese consulate in Toronto.

Tay, a Hong Kong-born human rights advocate, was named in December 2024 by Hong Kong authorities as one of six overseas dissidents subject to an international arrest warrant and monetary bounty. His photograph appeared on a wanted list offering cash rewards for information leading to his capture—an unprecedented move that Canadian officials condemned as a threat to national sovereignty.

“The decision by Hong Kong to issue international bounties and cancel the passports of democracy activists and former Hong Kong lawmakers is deplorable,” SITE stated today. “This attempt by Hong Kong authorities to conduct transnational repression abroad—including by issuing threats, intimidation or coercion against Canadians or those in Canada—will not be tolerated.”

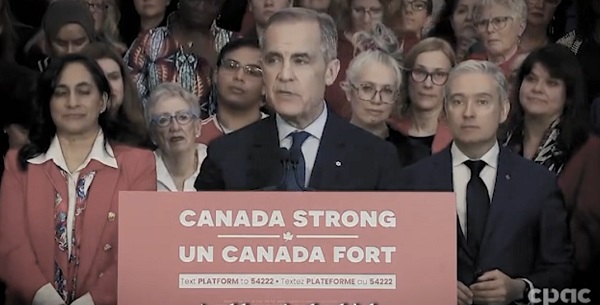

However, while facing an international wave of criticism, Prime Minister Mark Carney did tolerate his candidate’s alleged role in this activity. When asked earlier in the campaign whether he stood by Chiang, Carney said the Liberal MP retained his confidence. Chiang ultimately stepped down only after the RCMP confirmed it was reviewing the matter.

Chiang, who had been endorsed by Prime Minister Carney, was replaced as the Liberal candidate by Peter Yuen, the former Deputy Chief of the Toronto Police Service.

As The Bureau previously reported, Yuen traveled to Beijing in 2015 with a delegation of Ontario Chinese community leaders and politicians to attend a major military parade hosted by President Xi Jinping and the People’s Liberation Army—an event commemorating the Chinese Communist Party’s Second World War victory over Japan.

Yuen’s presence at that event—and his subsequent appearances at diaspora galas alongside leaders from the Confederation of Toronto Chinese Canadian Organizations (CTCCO), a group cited in national security reporting—has drawn media scrutiny.

Both Chiang and Yuen have stated that they strongly support Canada’s rule of law and deny any involvement in inappropriate activities.

According to SITE’s findings, Tay’s campaign has been the focus of two parallel strands of foreign influence since the beginning of the writ period. The first involves inauthentic and coordinated amplification of content related to Tay’s Hong Kong arrest warrant, including repeated efforts to cast doubt on his fitness for office. This activity has spanned multiple platforms commonly used by Chinese-speaking Canadians, including WeChat, Facebook, TikTok, RedNote, and Douyin.

The second strand is a deliberate suppression of Tay’s name in both simplified and traditional Chinese on platforms based in the People’s Republic of China. When users attempt to search for Tay, the platforms return only information related to the Hong Kong bounty—effectively erasing his campaign content and political biography from the digital public square.

While SITE noted that engagement levels with the disinformation remained limited, the timing, repetition, and cross-platform consistency led the Task Force to conclude this is a serious case of foreign interference.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

If you enjoy The Bureau, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe.

Invite Friends

Related