MacDonald Laurier Institute

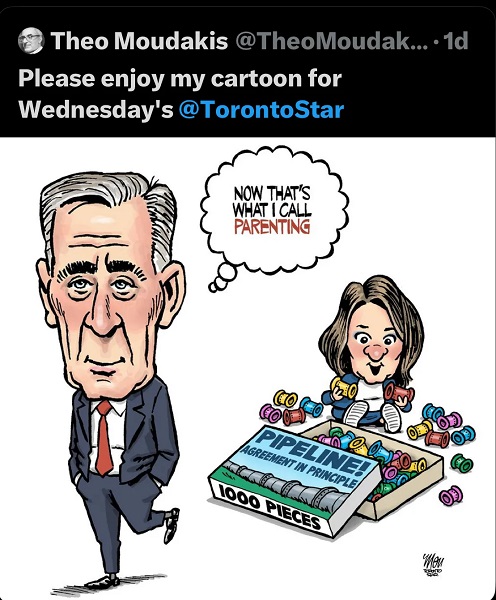

Trudeau is utterly determined to control the media: Peter Menzies

From the MacDonald Laurier Institute

By Peter Menzies

The government has broken new ground by involving itself in the business of judging the journalistic bona fides of news organizations.

The most progressive government in Canada’s history – the one under the towering command of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau – is fast building a reputation as the least liberal administration to have ruled the nation.

Just ask no less a personality than Piers Morgan.

“If you take Trudeau, for example, he banged on about Trump being a fascist, when he is the number one woke fascist in the world,” the English broadcaster and TV presenter recently told America’s Fox News. “The most woke human being alive.”

There’s little question Trudeau’s image as the world’s postmodern Prince Charming took a sharp turn for the worse two years ago with the unprecedented invocation of the Emergencies Act to suppress anti-government protests.

What’s more unsettling for civil libertarians is the thought that the Emergencies Act invocation wasn’t an aberration but part of a pattern of behaviour indicating that, while the ruling party may be Liberal, its instincts are anything but.

Its determination to control media – a hallmark of authoritarianism – has certainly raised eyebrows.

The Online Streaming Act, for instance, was only supposed to be about getting “money from web giants” such as Netflix and Disney+ to ensure government-preferred Canadian film and television content continued to be produced. But the act gave the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) sweeping powers over any audio or video content published on the internet, even including podcasts.

Fears were also raised that YouTube and TikTok would be forced by the CRTC to give preferential treatment to its approved content over that produced by those not subscribing to regulatory and Canada Media Fund expectations. The fact the CRTC is involved has further raised fears about the potential for a wave of censorship.

The regulator insists that it does not engage in censorship. But the fact it was doing exactly that – sanctioning Radio Canada for using the N-word and banning RT (Russian State television) while swearing that it wasn’t a censor – didn’t build public confidence in the credibility of its protestations.

When the CRTC accepted a complaint from Egale Canada (a 2SLGBTQI advocacy group) asking that it remove Fox News from its list of approved foreign broadcasters for “repeatedly and regularly” violating broadcasting standards, it was clear that the CRTC is open to making decisions on what Canadians may or may not watch. In other words: censorship. The Commission is composed of a chair, two vice chairs and six regional commissioners, each of whom is appointed by cabinet.

The government has also broken new ground by involving itself in the business of judging the journalistic bona fides of news organizations. Two programs initially announced as temporary – the Local Journalism Initiative and the Journalism Labour Tax Credit – have now doubled in size and appear to be permanent. A government-appointed panel decides which organizations are Qualified Canadian Journalism Organizations (and which aren’t). And while all involved insist the panel functions independently, it nevertheless reports to the Heritage Minister who reports to the Prime Minister’s Office which reports to a prime minister who appears obsessed with the need to control “misinformation” and “disinformation.”

That issue could very well be at the heart of what could become the Trudeau government’s most illiberal legislation yet – the Online Harms Act.

First promised in 2019 to ensure a suite of already-illegal behaviours including child porn and terrorism recruitment were suppressed, the Act’s core concept of giving a Digital Safety Commissioner power to order swift content removal has met with stiff resistance.

Pre-Elon Musk Twitter (X) put it this way:

“People around the world have been blocked from accessing Twitter and other services in a similar manner as the one proposed by Canada by multiple authoritarian governments (China, North Korea, and Iran for example) …”

Three Heritage Ministers have failed to find a way to legally reign in the internet in a fashion that satisfies the prime minister, so the matter has passed to the hands of Justice Minister Arif Virani.

Speculation in Ottawa is that Virani may be named as a Minister of State for Heritage, permitting him to try to come up with legislation that won’t – as did the Online Streaming Act and the Online News Act – trigger outrage when it’s introduced in the spring.

It remains to be seen if the Act will include extreme measures, like the policy resolution passed at last May’s Liberal convention to ban online media from using unnamed sources.

So, strap yourself in. The curtain may be about to rise on the most illiberal Liberal move yet.

International

Beijing’s blueprint for breaking Canada-U.S. unity

By Stephen Nagy for Inside Policy

For several decades, China has pursued a sophisticated campaign to fracture the world’s most integrated defense partnership—that between Canada and the United States.

Beijing’s strategy goes beyond typical diplomatic pressure: it systematically exploits every Canada-US disagreement, transforming routine alliance friction into seemingly irreconcilable divisions. This has become a degree of magnitude easier under US President Donald Trump, with his mercurial policy shifts towards Ottawa. The revelations about Chinese interference in Canadian elections from the Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections (SITE) Task Force – a body comprised of Canadian government and security officials which monitors elections threats – illuminate only one dimension of this comprehensive assault on North American solidarity.

Beijing’s strategic logic is to divide and conquer. By portraying Canada as sacrificing sovereignty for American interests while simultaneously painting legitimate Canadian security concerns as US-driven paranoia, Beijing paralyzes Ottawa’s decision-making and undermines continental defense cooperation.

The 2018 arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou crystallized China’s approach. When Canada honored its extradition treaty with the US by detaining Meng at the Vancouver airport, Beijing immediately framed this routine legal cooperation as evidence of Canadian subservience. Chinese state media didn’t simply criticize the arrest, they specifically portrayed Canada as “a pathetic clown” and “running dog of the US.”

Within nine days, China retaliated by detaining Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, holding them for 1,019 days. But Beijing’s messaging revealed its true objective. Chinese diplomats repeatedly demanded Canada “correct its mistake” by defying the U.S. extradition request. Ambassador Lu Shaye explicitly stated Canada could resolve the crisis by demonstrating “independence” from Washington.

The economic pressure followed the same pattern. China banned canola imports from two major Canadian companies in March 2019, citing “pests” but Chinese officials privately linked the ban to the Meng case. When targeting Canadian meat exports, Beijing’s timing again coincided with moments of US-Canada cooperation on Huawei restrictions.

China’s wedge strategy extends beyond retaliation to proactive exploitation of bilateral tensions. During the Keystone XL pipeline disputes, Chinese state media amplified Canadian grievances while offering Beijing as an “alternative partner” for energy exports. When the Biden administration cancelled the pipeline in 2021, Chinese diplomats and media immediately highlighted American “betrayal” of Canadian interests.

Similarly, during US-Canada disputes over softwood lumber tariffs and Buy American provisions, Chinese officials consistently present themselves as more reliable economic partners. The message is always the same: American protectionism harms Canadian workers, while China offers stable market access conveniently omitting Beijing’s own coercive trade practices.

On defense, China exploits Canadian concerns about Arctic sovereignty vis-à-vis the United States. When Washington challenges Canada’s claims over the Northwest Passage, Chinese media amplify these disagreements while positioning Beijing as respecting Canadian Arctic sovereignty – even as China declares itself a “near-Arctic state” and seeks military access to the region.

Recent intelligence revelations confirm China’s systematic attempts to influence Canadian politics specifically to create US-Canada friction. According to CSIS documents, Chinese intelligence assessed that a Liberal minority government would be less likely to follow Washington’s harder line on China. Beijing’s interference operations during the 2019 and 2021 elections specifically targeted Conservative candidates perceived as pro-American on China policy.

The Chinese United Front Work Department cultivates Canadian political and business figures through seemingly innocent organizations. A 2020 National Security and Intelligence Committee report found these groups specifically encouraged narratives about American “bullying” of Canada and promoted “made-in-Canada” foreign policies that coincidentally aligned with Chinese interests.

Chinese diplomats regularly exploit Canadian media to amplify anti-American sentiments. During USMCA negotiations, Chinese officials gave exclusive interviews to Canadian outlets sympathizing with “American strong-arm tactics.” When Canada considered banning Huawei from 5G networks, Chinese embassy officials published op-eds in Canadian newspapers warning against following “US tech hegemony.”

China’s wedge strategy carries profound implications for NORAD and continental defense. By creating friction between Ottawa and Washington, Beijing undermines the trust essential for integrated aerospace warning and maritime domain awareness. Chinese military academics have explicitly written about exploiting contradictions in US-Canada defense relations to complicate American force projection.

The stakes are rising as Arctic ice melts. China’s 2018 Arctic strategy specifically mentions differences between Arctic states as creating opportunities for Chinese involvement. Every US-Canada disagreement over Arctic waters provides Beijing openings to position itself as a stakeholder in North American approaches.

Canada and the United States must recognize that their occasional disagreements, normal in any alliance, are systematically weaponized by Beijing. In light of this, at least four responses are essential.

First, Canada and the United States should establish a joint commission on foreign interference that specifically monitors and publicly exposes attempts to exploit bilateral tensions. When China amplifies US-Canada disagreements, coordinated responses can demonstrate alliance resilience rather than division.

Second, create alliance resilience mechanisms that automatically trigger consultations when third parties attempt to exploit bilateral disputes. The Two Michaels crisis revealed how Beijing uses hostage-taking to pressure alliance relationships. A joint response protocol could reduce such leverage.

Third, strengthen Track II dialogues between Canadian and American civil society, business, and academic communities. These networks can maintain relationship continuity even during governmental tensions, reducing Beijing’s ability to exploit temporary political friction.

Fourth, develop coordinated strategic communications that acknowledge legitimate bilateral differences while emphasizing shared values and interests. Honest discussion of disagreements, paired with clear statements about alliance solidarity, can inoculate against external manipulation.

Canada faces the delicate balance of maintaining sovereign decision-making while recognizing that Beijing systematically exploits any daylight between Ottawa and Washington. This isn’t about choosing between independence and alliance. It’s about understanding how Canada’s adversaries weaponize that false choice.

The empirical evidence is clear. From the Meng affair to election interference, from trade coercion to Arctic maneuvering, China consistently pursues the same objective: transforming America from Canada’s closest ally into a source of resentment and suspicion. Every success in this strategy weakens not just bilateral ties but the entire democratic alliance system.

As the Chinese saying goes, 笑里藏刀—a dagger hidden behind a smile. While professing respect for Canadian sovereignty and offering economic partnerships, Beijing wages sophisticated political warfare designed to isolate democratic allies from each other. Recognizing this strategy is the first step toward defeating it. The strength of North American democracy lies not in the absence of disagreements but in the ability to resolve them without external exploitation. In an era of systemic rivalry, the US-Canada partnership must evolve from unconscious integration to conscious solidarity – as different nations with sovereign interests, but united in defending democratic values against authoritarian manipulation.

Stephen Nagy is a professor of politics and international studies at the International Christian University in Tokyo, and a senior fellow at the Macdonald Laurier Institute. The tentative title for his forthcoming monograph is “Navigating U.S. China Strategic Competition: Japan as an International Adapter Middle Power.”

International

Canada’s lost decade in foreign policy

By Joe Varner for Inside Policy

Our allies no longer doubt our values – they doubt our value.

Ten years after promising a return to global relevance, Canada’s foreign policy is defined not by what we do – but by what we fail to do – or fail to show up for.

When Prime Minister Justin Trudeau declared in 2015 that “Canada is back,” he promised to restore the country’s global voice and moral leadership. Ten years later, Canada is indeed back – but not in the way he intended. We are back to irrelevance, back to strategic incoherence, and back to being ignored by allies and adversaries alike. Across a decade of shifting crises, Canadian foreign policy under Prime Ministers Trudeau and Carney have become a case study in good intentions, miserable excuses, poor execution, and chronic unseriousness.

Nowhere was this clearer than in the fight against the Islamic State (ISIS). In October 2014, Stephen Harper’s government committed six CF-18 Hornets, two CP-140 Auroras, and a CC-150 Polaris refueller to the US-led coalition against ISIS, forming the backbone of Canada’s Operation Impact. Canadian aircraft conducted 251 airstrikes in the first six months, striking ISIS positions in Iraq and later Syria. When Trudeau took office in November 2015, his first major foreign-policy act was to withdraw the CF-18s, formally announced on February 8, 2016. The air campaign ended within weeks, replaced by a “train-advise-assist” mission that expanded our trainers in northern Iraq but sharply reduced our combat capability and influence. The decision was framed as moral sophistication but in practice it was viewed as a marked retreat.

The Syrian refugee crisis that erupted in 2015 became the emotional centrepiece of the Trudeau Liberals’ election campaign and his government’s first term – a symbolic gesture of compassion that ignored operational realities. Within weeks of taking office, Ottawa pledged to bring 25,000 Syrian refugees by February 2016, compressing a process that normally took a year into just 100 days. The first flights landed in Toronto and Montreal on December 10, 2015, to global and domestic applause. Behind the scenes, the RCMP and CSIS officials warned that the accelerated timeline left gaps in security screening, and the provinces struggled to provide housing and integration services. It was in the end humanitarian theatre – an election promise kept at the expense of process, capacity, and Canadian national security.

The Syrian refugee crisis saw the Trudeau government jettison Canada’s immigration policy for domestic political purposes. A few years later, when Canadians who had joined ISIS – so-called “foreign fighters” – began to return home between 2017 and 2023, the same government that had championed compassion responded with confusion. Roughly 60 foreign fighters returned to Canada, yet very few were successfully prosecuted under federal anti-terrorism laws. Instead, Ottawa relied on peace bonds, deradicalization programs, and surveillance costing millions of dollars per case. The spectacle intensified in 2022 and 2023 with the repatriation, under court order, of dozens of ISIS brides and their children from Kurdish detention camps. Many arrivals required extensive monitoring and support while families of ISIS victims protested that justice had been denied. The government’s oft-repeated line that “a Canadian is a Canadian” sounded inclusive; it came to symbolize moral inconsistency and policy drift. Critics viewed the hospitality bill reported in the popular press for ISIS Brides and children as an irresponsible fiscal and moral outrage.

Afghanistan was the ultimate test of Canada’s so-called “feminist foreign policy,” and it failed dramatically. When Kabul fell on August 15, 2021, Ottawa was unprepared despite months of intelligence warnings about the Taliban’s advance, and a knowledge of the Biden administration’s draw down and withdrawal. Operation Aegis, Canada’s evacuation effort, began late and ended early. Between August 4 and 26, the Canadian Armed Forces managed three evacuation flights, moving about 3,700 people while allies such as the US and the UK moved tens of thousands. The final RCAF flight departed before the US withdrawal on August 30, leaving hundreds of locally employed interpreters, contractors, and NGO partners stranded. Subsequent reports confirmed that internal direction from the defence minister led officials to prioritize select religious minorities like Sikhs with political connections over interpreters and Afghan women who had worked with Canadian agencies. Veterans and civil-society groups accused Ottawa of politicizing rescue lists while publicly boasting of compassion. For all the talk of empowering women and girls, the people most at risk were left behind in favour of Canadian domestic political interests in the Liberals’ Sikh support base.

In the Middle East, the 2018 rupture with Saudi Arabia remains one of the costliest self-inflicted diplomatic crises in recent memory. A tweet from the Foreign Minister calling for the release of a dissident sparked sweeping retaliation from Riyadh: the expulsion of Canada’s ambassador, suspension of trade and investment, cancellation of flights, and the withdrawal of thousands of Saudi students from Canadian universities. The Gulf Cooperation Council sided with Riyadh, leaving Canada isolated. It took more than four years to rebuild relations, and during that period Ottawa was excluded from key regional energy and security discussions. The episode became a cautionary tale of social-media diplomacy without strategy.

Canada’s approach to Israel and Palestine mirrored the pattern of ambiguity that has defined our broader foreign policy under the Trudeau and Carney liberals. Beginning in 2019, Ottawa reversed a long-standing position by supporting a UN resolution condemning Israeli settlements and endorsing Palestinian statehood – Canada’s first such vote in 14 years. When Hamas launched its October 7, 2023, terrorist attacks against Israel that killed more than 1,200 people, Canada’s initial response was cautious and slow. Statements emphasized proportionality and restraint rather than moral clarity. Two years later, in April 2025, Ottawa recognized a Palestinian state while hostilities with Hamas and other Iranian-backed groups were ongoing. The move alienated allies in Washington and Jerusalem, who warned that premature recognition risked legitimizing a territory still controlled by organizations committed to Israel’s destruction. President Trump went as far as to suggest that Canada had rewarded Hamas for the October 7 terror attack on Israel.

On Iran, engagement drifted into accommodation. After years of delay, Ottawa finally listed Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a terrorist entity in 2025 – long after allies such as the United States had done so and only following sustained pressure from Parliament and the families of victims of Flight PS752, which the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) shot down in January 2020, killing 55 Canadian citizens and 30 Canadian permanent residents. The long-overdue designation was more symbolic than strategic. Canada has become, by default, a refuge for individuals linked to the Iranian regime, including relatives of senior officials who live and invest here with impunity. Members of the Iranian diaspora report regular intimidation, surveillance, and threats from Tehran’s proxies operating on Canadian soil – activities that persist despite repeated calls for stronger counterintelligence and enforcement. For all its rhetorical commitment to human rights, Ottawa has failed to translate outrage into action. What passes for engagement with Iran today is less diplomacy than moral fatigue disguised as principle.

Relations with the US fared little better. The renegotiation of NAFTA in 2017–18 produced the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) – a deal that preserved supply management but conceded ground on automotive exports and dispute-resolution mechanisms. Tariffs on steel and aluminum followed in 2025, and Canada’s retaliatory levies could not hide the reality of diminished leverage. Chronic under–investment in defence and intelligence further eroded trust. When the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia formed the AUKUS pact in 2021 to share advanced defence technology, Canada was not consulted. In 2022, after years of frustrating delays, NORAD modernization hedged forward but by 2025 Canada had yet committed the full $38 billion required to upgrade continental defences. Years of delay in replacing the CF-18 fighter fleet key to NORAD – starting during the 2015 election campaign by the Trudeau Liberals – only resolved when Ottawa reversed course and ordered the same F-35s in 2023, the same planes that Trudeau once derided. In 2025, Prime Minister Carney placed the F-35 purchase under an election campaign review – reinforcing the impression of drift. To allies, Canada increasingly appeared as a moral commentator rather than a security contributor.

The federal government’s misreading of China compounded the damage. While allies recalibrated against Beijing’s coercion, Ottawa continued to chase trade and investment under the illusion that China could be both partner and rival to play off against the US. That fiction collapsed in December 2018 when Beijing detained Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor in retaliation for Canada’s arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou. The two men spent 1,020 days in secret detention under harsh conditions before their release in September 2021 – the same day Meng returned to China. Ottawa’s response throughout was hesitant, relying on “quiet diplomacy.” Even as other democracies expelled Chinese diplomats and banned Huawei, Canada delayed until 2022, becoming the last member of the “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance to act. Beijing’s execution and death sentences for Canadian citizens in 2019 elicited only muted protest by the Trudeau government. Despite fresh warnings of political interference in domestic affairs and elections campaigns, progress toward a foreign-influence registry remains halting. The cumulative impression is of a government reluctant to confront reality even as its allies in North America, Europe, and Asia are hardening their stance against Beijing.

Europe tells a similar story. The war in Ukraine has exposed the gulf between Canada’s rhetoric and its resources. Although NATO adopted its two-per cent-of-GDP defence-spending target in 2014, successive Canadian governments have treated it more as aspiration than obligation. Publicly, the Trudeau government endorsed the goal; privately, Trudeau told NATO leaders in 2017 that Canada would “never” reach it, a remark later reported in the Washington Post and confirmed by alliance officials. Eight years on, the numbers bear him out. Canada’s defence spending has hovered near 1.4 per cent of GDP, third from the bottom in NATO, even as Poland and the Baltic states have surged past four per cent and re-armed against Russia.

Under Prime Minister Carney, Ottawa now insists that the target will finally be met – on paper at least. In June 2025, the Carney government pledged to reach the spending benchmark by March 31, 2026, under what officials describe as a “re-baselined” accounting framework. In practice, much of the projected increase relies on broad definitions of “defence-related” spending – everything from veterans’ benefits and pensions to Arctic infrastructure and cybersecurity initiatives – that many allies may not accept as true military expenditure. To use a polite phrase, there is considerable voodoo math involved.

Equally puzzling is Ottawa’s rhetorical commitment to a new NATO 5-per cent-of-GDP goal without any credible path or plan to achieve it. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022, Canada’s military aid to Ukraine has remained constant but promised weapons shipments have been delayed or cancelled and participation in major NATO exercises curtailed by personnel and equipment shortages. At home, procurement paralysis has left the Canadian Army, Royal Canadian Navy and Royal Canadian Air Force under-equipped and increasingly unready for its primary role of defending Canada. Meanwhile, Ottawa refused for years to leverage Canada’s vast natural-gas reserves to help Europe reduce dependence on Russian energy, insisting there was “no business case” for Atlantic Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) exports. Only after 2025, under Carney, did talk of trade and energy re-engagement resume – too late to shape outcomes. In Brussels, Canada is now viewed less as a dependable ally than as a rhetorical one: a country that still talks like a middle power but spends like a minor one.

The sum of these choices is a Canada that no longer matters as it once did. We are too hesitant to deter, too divided to lead, and too sanctimonious to partner effectively. The language of virtue has replaced the practice of real strategy. Foreign policy is not theatre; it is the disciplined pursuit of national interest, backed by capability and clarity. For ten years we have confused applause at home and sometimes abroad with achievement and hashtags with hard power. The result is a diminished country adrift in an age of international danger – irrelevant in Washington, distrusted in Jerusalem, ignored in Riyadh, dismissed in Beijing, and barely tolerated in Brussels. Our allies no longer doubt our values – they doubt our value.

So, how do we not lose the next decade too? If Canada is to regain its standing, it must first rediscover seriousness. That means returning to the fundamentals of statecraft: credible defence spending, strong military power, clear strategic priorities, and the courage to act rather than advertise. Meeting NATO’s two-per cent commitment must be a floor, not a mirage built on creative accounting. Canada must modernize its armed forces, rebuild its defence industrial base, and restore operational readiness in the Arctic and abroad.

Diplomatically, Ottawa must re-anchor itself within the democratic alliance system – treating Washington, London, and Brussels as indispensable partners rather than convenient props. Engagement with China should be rooted in deterrence and human-rights enforcement, not wishful economics. Canada needs to field a well-equipped brigade in Latvia and lead by example to deter Russia. In the Middle East, Canada must again stand firmly with Israel’s right to exist while pushing back on Iran and its regional proxies.

Canada must once again take a principled stance on human rights and targeted economic development compatible with our national interests and the strategic realities on the ground in regions like Africa.

At home, foreign policy should once again serve national interest rather than transactional domestic political theatre. Canada’s influence was never built on slogans but on capability, credibility, and sacrifice – from Vimy Ridge to Juno Beach and from Kapyong to Kandahar. Those qualities are not lost; they are merely dormant. The path back is not through hashtags or press conferences, but through purpose, power, and principle. Only when Canada stops pretending to lead and starts preparing to lead will the world take us seriously again. If “Canada is back” is ever to mean something again, it must be said not from a podium, but from a position of strength. Power respects power – and until Canada remembers that – no one will remember us.

Joe Varner is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and the Center for North American Prosperity and Security, and deputy director of the Conference of Defence Associations.

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoConservative MP Leslyn Lewis slams Liberal plan targeting religious exemption in hate speech bil

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada’s climate agenda hit business hard but barely cut emissions

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoNews RFK Jr.’s vaccine committee to vote on ending Hepatitis B shot recommendation for newborns

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoFBI may have finally nabbed the Jan. 6 pipe bomber

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoIntegration Or Indignation: Whose Strategy Worked Best Against Trump?

-

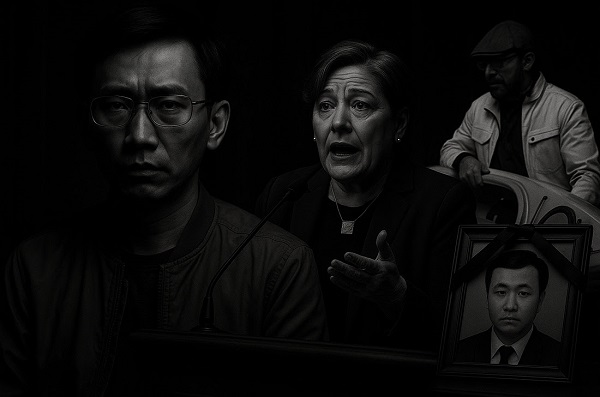

espionage1 day ago

espionage1 day agoDigital messages reportedly allege Chinese police targeted dissident who died suspiciously near Vancouver

-

MAiD1 day ago

MAiD1 day ago101-year-old woman chooses assisted suicide — press treats her death as a social good

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney’s Toronto cabinet meetings cost $530,000