Fraser Institute

Time to finally change the Canada Health Act for the sake of patients

From the Fraser Institute

Back in 1984, the Canada Health Act (CHA) received royal assent and has since reached near iconic status. At the same time, under its purview, the Canadian health-care system has become one of the least accessible—and most expensive—universal health-care systems in the developed world.

Clearly, policymakers should reform the CHA to reflect a more contemporary understanding of how to structure a truly world-class universal health-care system.

Consider for a moment the remarkably poor state of access to health care in Canada today. According to international comparisons of universal health-care systems, we endure some of the lowest access to physicians, medical technologies and hospital beds in the developed world. Wait times for health care in Canada also routinely rank among the longest in the developed world.

None of this is new. Canada’s poor ranking in the availability of services reaches back at least two decades. And wait times for health care have nearly tripled since the early 1990s. Back then, in 1993, Canadians could expect to wait 9.3 weeks for medical treatment after GP referral compared to 30 weeks in 2024.

This is all happening despite Canadians paying for one of the world’s most expensive universal-access health-care systems. And this brings us back to the CHA, which contains the federal government’s requirements for provincial policymaking. To receive their full federal cash transfers for health care from Ottawa, provinces must abide by CHA rules and regulations. And therein lies the rub.

We can find the solutions to our health-care woes in other countries such as Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Australia, which all provide more timely access to quality care. Every one of these countries requires patient cost-sharing for physician and hospital services, and private competition in the delivery of universally accessible services with money following patients to hospitals and surgical clinics. And all these countries allow private purchases of health care, as this reduces the burden on the publicly-funded system and creates a valuable pressure valve for it.

Unfortunately for Canadians, the CHA expressly disallows requiring patients to share the cost of treatment while the CHA’s often vaguely defined terms and conditions have been used by federal governments to discourage a larger role for the private sector in the delivery of health-care services. At the same time, every new federal commitment to fix health care means increased provincial reliance on Ottawa. In 2024-25, federal cash transfers for health care are expected to total $52 billion, which means there’s $52 billion on the line for perceived non-compliance with the CHA. In short, this is why the provinces beholden to a policy approach that’s clearly failing Canadians.

So, what to do?

For starters, Ottawa should learn from its own welfare reforms in the 1990s, which reduced federal transfers and allowed provinces more flexibility with policymaking. The resulting period of provincial policy innovation reduced welfare dependency and government spending on social assistance (i.e. savings for taxpayers). When Ottawa stepped back and allowed the provinces to vary policy to their unique circumstances, Canadians got improved outcomes for fewer dollars.

We need that same approach for health care today, and it begins with the federal government reforming the CHA to expressly allow provinces the ability to explore alternate policy approaches, while maintaining the foundational principles of universality.

Next, the federal government should either hold cash transfers for health care constant (in nominal terms), reduce them or eliminate them entirely with a concordant reduction in federal taxes. By reducing (or eliminating) the pool of cash tied to the strings of the CHA, provinces would have greater freedom to pursue reform policies they consider to be in the best interests of their residents without federal intervention.

After 40 years, it’s high time to remove ambiguity and minimize uncertainty—and the potential for politically motivated interpretations—of the CHA. If federal policymakers want Canadians to finally have access to world-class health care, they should allow the provinces to choose their own set of universal health-care policies. The first step is to fix the 40-year-old legislation that has held the provinces back.

Business

Dark clouds loom over Canada’s economy in 2026

From the Fraser Institute

The dawn of a new year is an opportune time to ponder the recent performance of Canada’s $3.4 trillion economy. And the overall picture is not exactly cheerful.

Since the start of 2025, our principal trading partner has been ruled by a president who seems determined to unravel the post-war global economic and security order that provided a stable and reassuring backdrop for smaller countries such as Canada. Whether the Canada-U.S.-Mexico trade agreement (that President Trump himself pushed for) will even survive is unclear, underscoring the uncertainty that continues to weigh on business investment in Canada.

At the same time, Europe—representing one-fifth of the global economy—remains sluggish, thanks to Russia’s relentless war of choice against Ukraine, high energy costs across much of the region, and the bloc’s waning competitiveness. The huge Chinese economy has also lost a step. None of this is good for Canada.

Yet despite a difficult external environment, Canada’s economy has been surprisingly resilient. Gross domestic product (GDP) is projected to grow by 1.7 per cent (after inflation) this year. The main reason is continued gains in consumer spending, which accounts for more than three-fifths of all economic activity. After stripping out inflation, money spent by Canadians on goods and services is set to climb by 2.2 per cent in 2025, matching last year’s pace. Solid consumer spending has helped offset the impact of dwindling exports, sluggish business investment and—since 2023—lacklustre housing markets.

Another reason why we have avoided a sharper economic downturn is that the Trump administration has, so far, exempted most of Canada’s southbound exports from the president’s tariff barrage. This has partially cushioned the decline in Canada’s exports—particularly outside of the steel, aluminum, lumber and auto sectors, where steep U.S. tariffs are in effect. While exports will be lower in 2025 than the year before, the fall is less dramatic than analysts expected 6 to 8 months ago.

Although Canada’s economy grew in 2025, the job market lost steam. Employment growth has softened and the unemployment rate has ticked higher—it’s on track to average almost 7 per cent this year, up from 5.4 per cent two years ago. Unemployment among young people has skyrocketed. With the economy showing little momentum, employment growth will remain muted next year.

Unfortunately, there’s nothing positive to report on the investment front. Adjusted for inflation, private-sector capital spending has been on a downward trajectory for the last decade—a long-term trend that can’t be explained by Trump’s tariffs. Canada has underperformed both the United States and several other advanced economies in the amount of investment per employee. The investment gap with the U.S. has widened steadily since 2014. This means Canadian workers have fewer and less up-to-date tools, equipment and technology to help them produce goods and services compared to their counterparts in the U.S. (and many other countries). As a result, productivity growth in Canada has been lackluster, narrowing the scope for wage increases.

Preliminary data indicate that both overall non-residential investment and business capital spending on machinery, equipment and advanced technology products will be down again in 2025. Getting clarity on the future of the Canada-U.S. trade relationship will be key to improving the business environment for private-sector investment. Tax and regulatory policy changes that make Canada a more attractive choice for companies looking to invest and grow are also necessary. This is where government policymakers should direct their attention in 2026.

Alberta

Alberta Next Panel calls for less Ottawa—and it could pay off

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill

Last Friday, less than a week before Christmas, the Smith government quietly released the final report from its Alberta Next Panel, which assessed Alberta’s role in Canada. Among other things, the panel recommends that the federal government transfer some of its tax revenue to provincial governments so they can assume more control over the delivery of provincial services. Based on Canada’s experience in the 1990s, this plan could deliver real benefits for Albertans and all Canadians.

Federations such as Canada typically work best when governments stick to their constitutional lanes. Indeed, one of the benefits of being a federalist country is that different levels of government assume responsibility for programs they’re best suited to deliver. For example, it’s logical that the federal government handle national defence, while provincial governments are typically best positioned to understand and address the unique health-care and education needs of their citizens.

But there’s currently a mismatch between the share of taxes the provinces collect and the cost of delivering provincial responsibilities (e.g. health care, education, childcare, and social services). As such, Ottawa uses transfers—including the Canada Health Transfer (CHT)—to financially support the provinces in their areas of responsibility. But these funds come with conditions.

Consider health care. To receive CHT payments from Ottawa, provinces must abide by the Canada Health Act, which effectively prevents the provinces from experimenting with new ways of delivering and financing health care—including policies that are successful in other universal health-care countries. Given Canada’s health-care system is one of the developed world’s most expensive universal systems, yet Canadians face some of the longest wait times for physicians and worst access to medical technology (e.g. MRIs) and hospital beds, these restrictions limit badly needed innovation and hurt patients.

To give the provinces more flexibility, the Alberta Next Panel suggests the federal government shift tax points (and transfer GST) to the provinces to better align provincial revenues with provincial responsibilities while eliminating “strings” attached to such federal transfers. In other words, Ottawa would transfer a portion of its tax revenues from the federal income tax and federal sales tax to the provincial government so they have funds to experiment with what works best for their citizens, without conditions on how that money can be used.

According to the Alberta Next Panel poll, at least in Alberta, a majority of citizens support this type of provincial autonomy in delivering provincial programs—and again, it’s paid off before.

In the 1990s, amid a fiscal crisis (greater in scale, but not dissimilar to the one Ottawa faces today), the federal government reduced welfare and social assistance transfers to the provinces while simultaneously removing most of the “strings” attached to these dollars. These reforms allowed the provinces to introduce work incentives, for example, which would have previously triggered a reduction in federal transfers. The change to federal transfers sparked a wave of reforms as the provinces experimented with new ways to improve their welfare programs, and ultimately led to significant innovation that reduced welfare dependency from a high of 3.1 million in 1994 to a low of 1.6 million in 2008, while also reducing government spending on social assistance.

The Smith government’s Alberta Next Panel wants the federal government to transfer some of its tax revenues to the provinces and reduce restrictions on provincial program delivery. As Canada’s experience in the 1990s shows, this could spur real innovation that ultimately improves services for Albertans and all Canadians.

-

Business1 day ago

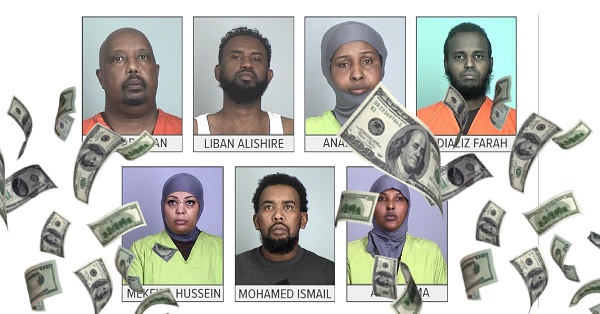

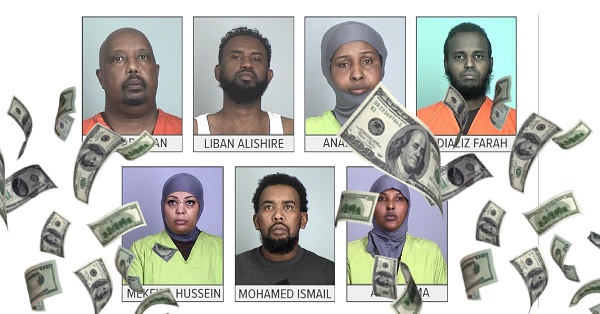

Business1 day agoICYMI: Largest fraud in US history? Independent Journalist visits numerous daycare centres with no children, revealing massive scam

-

Alberta18 hours ago

Alberta18 hours agoAlberta project would be “the biggest carbon capture and storage project in the world”

-

Energy15 hours ago

Energy15 hours agoCanada’s debate on energy levelled up in 2025

-

Business16 hours ago

Business16 hours agoSocialism vs. Capitalism

-

Energy17 hours ago

Energy17 hours agoNew Poll Shows Ontarians See Oil & Gas as Key to Jobs, Economy, and Trade

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoFeds pull the plug on small business grants to Minnesota after massive fraud reports

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoDOOR TO DOOR: Feds descend on Minneapolis day cares tied to massive fraud

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada needs serious tax cuts in 2026