Brownstone Institute

The Selfish Collective

Originally published by the Brownstone Institute

BY

Much of the debate surrounding Covid — and increasingly now, other crises — has been framed in terms of individualism vs. collectivism. The idea is that individualists are motivated by self-interest, while collectivists put their community first.

This dichotomy paints the collective voice, or the community, as the prosocial option of two choices, where the threat lies with recalcitrant individuals holding everyone else back. The individual threatens the common good because they won’t go along with the program, the program everyone else has decided upon, which is what is best for everyone.

There are several immediate problems with this logic. It is a string of loaded assumptions and false equivalencies: first, it equates the philosophy of collectivism with the idea of prosocial motivation; secondly, it equates prosocial behavior with conformity to the collective voice.

Merriam-Webster defines collectivism as follows:

1 : a political or economic theory advocating collective control especially over production and distribution also : a system marked by such control

2 : emphasis on collective rather than individual action or identity

Note that there is no mention here of internal motivations — and rightly so. The philosophy of collectivism emphasizes collectively organized behavioral patterns over those of the individual. There is no prescription for these reasons. They could be prosocially motivated, or selfish.

After the past couple of years of analyzing collectivist behavior during the Covid crisis, I have come to the conclusion that it is just as likely as individualism to be motivated by self-interest. In fact, in many ways, I would say it is easier to attain one’s selfish interests by aligning oneself with a collective than to do so individually. If a collective composed primarily of self-interested individuals unites over a common goal, I call this phenomenon “the selfish collective.”

When “Common Good” is Not Collective Will

One of the most simple examples I can give of a selfish collective is that of a homeowner’s association (HOA). The HOA is a group of individuals who have unified into a collective in order to protect each of their own self-interests. Their members want to preserve their own property values, or certain aesthetic characteristics of their neighborhood environment. In order to achieve this they often feel comfortable dictating what their neighbors can and cannot do on their own property, or even in the privacy of their own homes.

They are widely despised for making homeowners’ lives miserable, and for good reason: if they claim the right to safeguard the value of their own investments, doesn’t it stand to reason that other homeowners, with perhaps different priorities, have a similar right to rule over the little corner of the world they paid hundreds of thousands of dollars for?

The selfish collective resembles the political concept of “tyranny of the majority,” of which Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America:

“So what is a majority taken as a whole, if not an individual who has opinions and, most often, interests contrary to another individual called the minority. Now, if you admit that an individual invested with omnipotence can abuse it against his adversaries, why would you not admit the same thing for the majority?”

Social groups are made up of individuals. And if individuals can be selfish, then collectives made up of individuals with common interests can be equally selfish, attempting to steamroll their visions over the rights of others.

However, the selfish collective is not necessarily comprised of a majority. It could just as easily be a loud minority. It is characterized not by its size, but by its inherent attitude of entitlement: its insistence that other people must sacrifice increasingly high-level priorities in order to accommodate increasingly trivial priorities of its own.

This inverse relationship of priority valuation is what belies the true nature of the selfish collective, and distinguishes its motives from the true “common good.” Someone motivated by genuine social concern asks the question: “What are the priorities and goals of all community members, and how can we try to satisfy these priorities in a way that everyone finds acceptable?”

Social concern involves negotiation, tolerance of value differences, and the ability to compromise or see nuance. It involves genuinely caring about what others want — even (and especially) when they have different priorities. When this concern extends only to those in one’s “in-group,” it may appear to be prosocial, but is actually an extension of self-interest known as collective narcissism.

Collective Narcissism and Conformity

From the perspective of the selfish individual, collectivism provides a host of opportunities for achieving one’s goals — perhaps better than one could on one’s own. For the manipulative and calculating, the collective is easier to hide behind, and the ideal of the “greater good” can be weaponized to win moral support. For cowards and bullies, the strength of numbers is emboldening, and can help them overpower weaker individuals or coalitions. For more conscientious individuals, it can be tempting to justify one’s natural selfish inclinations by convincing oneself the group holds the moral edge.

In social psychology, collective narcissism is the extension of one’s ego beyond oneself to a group or collective to which one belongs. While not all the individuals involved in such a collective are necessarily narcissists themselves, the emergent “personality” of the group mirrors the traits of narcissistic individuals.

According to Dr. Les Carter, a therapist and creator of the Surviving Narcissism YouTube channel, these traits include the following:

- A heavy emphasis on binary themes

- Discouraging free thinking

- Prioritizing conformity

- Imperative thinking

- Distrusting or dishonoring differences of opinion

- Pressure to display loyalty

- An idealized group self-image

- Anger is only one wrong opinion away

What all of these traits have in common is an emphasis on unity rather than harmony. Instead of seeking coexistence among people or factions with differing values (the “social good” that includes everyone), the in-group defines a set of priorities to which all others must adapt. There is one “correct way,” and anything outside it has no merit. There is no compromise of values. Collective narcissism is the psychology of the selfish collective.

The Hidden Logic of Lockdown

Proponents of Covid restrictions and mandates have typically claimed they were motivated by social concern, while painting their opponents as antisocial menaces. But does this bear out?

I have no doubt that a great many people, motivated by compassion and by civic duty, genuinely strove to serve the greater good through following these measures. But at its core, I argue that the pro-mandate case follows the logic of the selfish collective.

The logic goes something like this:

- SARS-CoV-2 is a dangerous virus.

- Restrictions and mandates will “stop the spread” of the virus, thereby saving lives and shielding people from the harm it causes.

- We have a moral duty as a society to shield people from harm wherever possible.

- Therefore, we have a moral duty to enact restrictions and mandates.

Never mind the veracity of any one of these claims, which has already been the subject of endless debate over the past two and a half years. Let’s instead focus on the logic. Let’s assume for a second that each of the three premises above were true:

How dangerous would the virus have to be in order for the restrictions and mandates to be justified? Is any level of “dangerousness” enough? Or is there a threshold? Can this threshold be quantified, and if so, at what point do we meet it?

Likewise, how many people would restrictions and mandates need to save or shield before they are considered to be worthwhile measures, and what level of collateral damage from the measures is considered acceptable? Can we quantify these thresholds either?

What other “socially beneficial outcomes” are desirable, and from whose perspective? What other social priorities exist for various factions within the collective? What logic do we use to weigh these priorities against each other? How can we respect priorities that may weigh a lot to their respective advocates, but which directly compete or clash with the “socially beneficial outcome” of eliminating the virus?

The answers to these questions would help us organize our priorities within a larger, more complex social landscape. No one social issue exists in a vacuum; “Responding to SARS-CoV-2” is one possible social priority out of millions. What gives this priority in particular precedence over any of the others? Why does it get to be the top and only priority?

To date I have never seen a satisfactory answer to any of the above questions from proponents of mandates. What I have seen are abundant logical fallacies used to justify their preferred course of action, attempts to exclude or minimize all other concerns, rejection of or silence regarding inconvenient data, dismissal of alternative opinions, and an insistence that there is one “correct” path forward to which all others must conform.

The reason for this, I would argue, is that the answers don’t matter. It doesn’t matter how dangerous the virus is, it doesn’t matter how much collateral damage is done, it doesn’t matter how many people might die or be saved, it doesn’t matterwhat other “socially beneficial outcomes” we might strive for, and it doesn’t matter what anybody else might prioritize or value.

In the logic of the selfish collective, the needs and desires of others are afterthoughts, to be attended if, and only if, there is something left over once they get their way.

This particular collective has made “responding to SARS-CoV-2” their top priority. And in pursuit of that priority, all others can be sacrificed. This one priority has been granted carte blanche to invade all other aspects of social life, simply because the selfish collective has decided it is important. And in pursuit of this goal, increasingly trivial sub-priorities that are deemed relevant can now take precedence over increasingly higher-level priorities of other social factions.

The end result of this is the absurd micromanagement of other people’s lives, and the simultaneous cruel dismissal of their deepest loves and needs. People were forbidden from saying goodbye to dying parents and relatives; romantic partners were separated from each other; and cancer patients died because they were denied access to treatment, just to name a few of these cruelties. Why were these people told their concerns didn’t matter? Why did they have to be the ones to sacrifice?

The argument of the selfish collective is that individual freedom must end as soon as it risks negatively impacting the group. But this is a smokescreen: there is no unified collective perceiving “negative impacts” in a homogeneous way. The “collective” is a group of individuals, each with different sets of priorities and value systems, only some of whom have coalesced around a specific issue.

At the root of this entire discussion lies the following question: How, on a macro scale, should society allocate importance to the diverse, competing priorities held by the individuals that make it up?

The selfish collective, which represents a particular faction, attempts to obscure the nuance of this question by trying to conflate themselves with the entire group. They try to make it seem as if their own priorities are the only factors under consideration, while dismissing other elements of the debate. It is a fallacy of composition mixed with a fallacy of suppressed evidence.

By magnifying their own concerns and generalizing them to the whole group, the selfish collective makes it seem as if their goals reflect “the good of everyone.” This has a reinforcing effect because the more they focus attention on their own priorities relative to others, the more others will come to believe those priorities are worthy of attention, adding to the impression that “everyone” supports them. Those with different value systems are gradually subsumed into a collective unity, or erased.

This does not strike me as prosocial behavior — it is deception, egotism, and tyranny.

A truly prosocial approach would not shut out all other goals and insist on one way forward. It would take into account the different priorities and viewpoints of various factions or individuals, approach them with respect, and ask how to best facilitate some sort of harmony among their needs. Instead of prescribing behavior onto others it would advocate for dialogue and open debate, and it would celebrate differences of opinion.

A prosocial approach doesn’t elevate some nebulous, abstract, and misleading image of a “collective” above the humanity and diversity of the individuals who make it up.

A prosocial approach makes space for freedom.

Brownstone Institute

If the President in the White House can’t make changes, who’s in charge?

From the Brownstone Institute

By

Who Controls the Administrative State?

President Trump on March 20, 2025, ordered the following: “The Secretary of Education shall, to the maximum extent appropriate and permitted by law, take all necessary steps to facilitate the closure of the Department of Education.”

That is interesting language: to “take all necessary steps to facilitate the closure” is not the same as closing it. And what is “permitted by law” is precisely what is in dispute.

It is meant to feel like abolition, and the media reported it as such, but it is not even close. This is not Trump’s fault. The supposed authoritarian has his hands tied in many directions, even over agencies he supposedly controls, the actions of which he must ultimately bear responsibility.

The Department of Education is an executive agency, created by Congress in 1979. Trump wants it gone forever. So do his voters. Can he do that? No but can he destaff the place and scatter its functions? No one knows for sure. Who decides? Presumably the highest court, eventually.

How this is decided – whether the president is actually in charge or really just a symbolic figure like the King of Sweden – affects not just this one destructive agency but hundreds more. Indeed, the fate of the whole of freedom and functioning of constitutional republics may depend on the answer.

All burning questions of politics today turn on who or what is in charge of the administrative state. No one knows the answer and this is for a reason. The main functioning of the modern state falls to a beast that does not exist in the Constitution.

The public mind has never had great love for bureaucracies. Consistent with Max Weber’s worry, they have put society in an impenetrable “iron cage” built of bloodless rationalism, needling edicts, corporatist corruption, and never-ending empire-building checked by neither budgetary restraint nor plebiscite.

Today’s full consciousness of the authority and ubiquity of the administrative state is rather new. The term itself is a mouthful and doesn’t come close to describing the breadth and depth of the problem, including its root systems and retail branches. The new awareness is that neither the people nor their elected representatives are really in charge of the regime under which we live, which betrays the whole political promise of the Enlightenment.

This dawning awareness is probably 100 years late. The machinery of what is popularly known as the “deep state” – I’ve argued there are deep, middle, and shallow layers – has been growing in the US since the inception of the civil service in 1883 and thoroughly entrenched over two world wars and countless crises at home and abroad.

The edifice of compulsion and control is indescribably huge. No one can agree precisely on how many agencies there are or how many people work for them, much less how many institutions and individuals work on contract for them, either directly or indirectly. And that is just the public face; the subterranean branch is far more elusive.

The revolt against them all came with the Covid controls, when everyone was surrounded on all sides by forces outside our purview and about which the politicians knew not much at all. Then those same institutional forces appear to be involved in overturning the rule of a very popular politician whom they tried to stop from gaining a second term.

The combination of this series of outrages – what Jefferson in his Declaration called “a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object” – has led to a torrent of awareness. This has translated into political action.

A distinguishing mark of Trump’s second term has been an optically concerted effort, at least initially, to take control of and then curb administrative state power, more so than any executive in living memory. At every step in these efforts, there has been some barrier, even many on all sides.

There are at least 100 legal challenges making their way through courts. District judges are striking down Trump’s ability to fire workers, redirect funding, curb responsibilities, and otherwise change the way they do business.

Even the signature early achievement of DOGE – the shuttering of USAID – has been stopped by a judge with an attempt to reverse it. A judge has even dared tell the Trump administration who it can and cannot hire at USAID.

Not a day goes by when the New York Times does not manufacture some maudlin defense of the put-upon minions of the tax-funded managerial class. In this worldview, the agencies are always right, whereas any elected or appointed person seeking to rein them in or terminate them is attacking the public interest.

After all, as it turns out, legacy media and the administrative state have worked together for at least a century to cobble together what was conventionally called “the news.” Where would the NYT or the whole legacy media otherwise be?

So ferocious has been the pushback against even the paltry successes and often cosmetic reforms of MAGA/MAHA/DOGE that vigilantes have engaged in terrorism against Teslas and their owners. Not even returning astronauts from being “lost in space” has redeemed Elon Musk from the wrath of the ruling class. Hating him and his companies is the “new thing” for NPCs, on a long list that began with masks, shots, supporting Ukraine, and surgical rights for gender dysphoria.

What is really at stake, more so than any issue in American life (and this applies to states around the world) – far more than any ideological battles over left and right, red and blue, or race and class – is the status, power, and security of the administrative state itself and all its works.

We claim to support democracy yet all the while, empires of command-and-control have arisen among us. The victims have only one mechanism available to fight back: the vote. Can that work? We do not yet know. This question will likely be decided by the highest court.

All of which is awkward. It is impossible to get around this US government organizational chart. All but a handful of agencies live under the category of the executive branch. Article 2, Section 1, says: “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.”

Does the president control the whole of the executive branch in a meaningful way? One would think so. It’s impossible to understand how it could be otherwise. The chief executive is…the chief executive. He is held responsible for what these agencies do – we certainly blasted away at the Trump administration in the first term for everything that happened under his watch. In that case, and if the buck really does stop at the Oval Office desk, the president must have some modicum of control beyond the ability to tag a marionette to get the best parking spot at the agency.

What is the alternative to presidential oversight and management of the agencies listed in this branch of government? They run themselves? That claim means nothing in practice.

For an agency to be deemed “independent” turns out to mean codependency with the industries regulated, subsidized, penalized, or otherwise impacted by its operations. HUD does housing development, FDA does pharmaceuticals, DOA does farming, DOL does unions, DOE does oil and turbines, DOD does tanks and bombs, FAA does airlines, and so on It goes forever.

That’s what “independence” means in practice: total acquiescence to industrial cartels, trade groups, and behind-the-scenes systems of payola, blackmail, and graft, while the powerless among the people live with the results. This much we have learned and cannot unlearn.

That is precisely the problem that cries out for a solution. The solution of elections seems reasonable only if the people we elected actually have the authority over the thing they seek to reform.

There are criticisms of the idea of executive control of executive agencies, which is really nothing other than the system the Founders established.

First, conceding more power to the president raises fears that he will behave like a dictator, a fear that is legitimate. Partisan supporters of Trump won’t be happy when the precedent is cited to reverse Trump’s political priorities and the agencies turn on red-state voters in revenge.

That problem is solved by dismantling agency power itself, which, interestingly, is mostly what Trump’s executive orders have sought to achieve and which the courts and media have worked to stop.

Second, one worries about the return of the “spoils system,” the supposedly corrupt system by which the president hands out favors to friends in the form of emoluments, a practice the establishment of the civil service was supposed to stop.

In reality, the new system of the early 20th century fixed nothing but only added another layer, a permanent ruling class to participate more fully in a new type of spoils system that operated now under the cloak of science and efficiency.

Honestly, can we really compare the petty thievery of Tammany Hall to the global depredations of USAID?

Third, it is said that presidential control of agencies threatens to erode checks and balances. The obvious response is the organizational chart above. That happened long ago as Congress created and funded agency after agency from the Wilson to the Biden administration, all under executive control.

Congress perhaps wanted the administrative state to be an unannounced and unaccountable fourth branch, but nothing in the founding documents created or imagined such a thing.

If you are worried about being dominated and destroyed by a ravenous beast, the best approach is not to adopt one, feed it to adulthood, train it to attack and eat people, and then unleash it.

The Covid years taught us to fear the power of the agencies and those who control them not just nationally but globally. The question now is two-fold: what can be done about it and how to get from here to there?

Trump’s executive order on the Department of Education illustrates the point precisely. His administration is so uncertain of what it does and can control, even of agencies that are wholly executive agencies, listed clearly under the heading of executive agencies, that it has to dodge and weave practical and legal barriers and land mines, even in its own supposed executive pronouncements, even to urge what might amount to be minor reforms.

Whoever is in charge of such a system, it is clearly not the people.

Brownstone Institute

The New Enthusiasm for Slaughter

From the Brownstone Institute

By

What War Means

My mother once told me how my father still woke up screaming in the night years after I was born, decades after the Second World War (WWII) ended. I had not known – probably like most children of those who fought. For him, it was visions of his friends going down in burning aircraft – other bombers of his squadron off north Australia – and to be helpless, watching, as they burnt and fell. Few born after that war could really appreciate what their fathers, and mothers, went through.

Early in the movie Saving Private Ryan, there is an extended D-Day scene of the front doors of the landing craft opening on the Normandy beaches, and all those inside being torn apart by bullets. It happens to one landing craft after another. Bankers, teachers, students, and farmers being ripped in pieces and their guts spilling out whilst they, still alive, call for help that cannot come. That is what happens when a machine gun opens up through the open door of a landing craft, or an armored personnel carrier, of a group sent to secure a tree line.

It is what a lot of politicians are calling for now.

People with shares in the arms industry become a little richer every time one of those shells is fired and has to be replaced. They gain financially, and often politically, from bodies being ripped open. This is what we call war. It is increasingly popular as a political strategy, though generally for others and the children of others.

Of course, the effects of war go beyond the dismembering and lonely death of many of those fighting. Massacres of civilians and rape of women can become common, as brutality enables humans to be seen as unwanted objects. If all this sounds abstract, apply it to your loved ones and think what that would mean.

I believe there can be just wars, and this is not a discussion about the evil of war, or who is right or wrong in current wars. Just a recognition that war is something worth avoiding, despite its apparent popularity amongst many leaders and our media.

The EU Reverses Its Focus

When the Brexit vote determined that Britain would leave the European Union (EU), I, like many, despaired. We should learn from history, and the EU’s existence had coincided with the longest period of peace between Western European States in well over 2,000 years.

Leaving the EU seemed to be risking this success. Surely, it is better to work together, to talk and cooperate with old enemies, in a constructive way? The media, and the political left, center, and much of the right seemed at that time, all of nine years ago, to agree. Or so the story went.

We now face a new reality as the EU leadership scrambles to justify continuing a war. Not only continuing, but they had been staunchly refusing to even countenance discussion on ending the killing. It has taken a new regime from across the ocean, a subject of European mockery, to do that.

In Europe, and in parts of American politics, something is going on that is very different from the question of whether current wars are just or unjust. It is an apparent belief that advocacy for continued war is virtuous. Talking to leaders of an opposing country in a war that is killing Europeans by the tens of thousands has been seen as traitorous. Those proposing to view the issues from both sides are somehow “far right.”

The EU, once intended as an instrument to end war, now has a European rearmament strategy. The irony seems lost on both its leaders and its media. Arguments such as “peace through strength” are pathetic when accompanied by censorship, propaganda, and a refusal to talk.

As US Vice-President JD Vance recently asked European leaders, what values are they actually defending?

Europe’s Need for Outside Help

A lack of experience of war does not seem sufficient to explain the current enthusiasm to continue them. Architects of WWII in Europe had certainly experienced the carnage of the First World War. Apart from the financial incentives that human slaughter can bring, there are also political ideologies that enable the mass death of others to be turned into an abstract and even positive idea.

Those dying must be seen to be from a different class, of different intelligence, or otherwise justifiable fodder to feed the cause of the Rules-Based Order or whatever other slogan can distinguish an ‘us’ from a ‘them’…While the current incarnation seems more of a class thing than a geographical or nationalistic one, European history is ripe with variations of both.

Europe appears to be back where it used to be, the aristocracy burning the serfs when not visiting each other’s clubs. Shallow thinking has the day, and the media have adapted themselves accordingly. Democracy means ensuring that only the right people get into power.

Dismembered European corpses and terrorized children are just part of maintaining this ideological purity. War is acceptable once more. Let’s hope such leaders and ideologies can be sidelined by those beyond Europe who are willing to give peace a chance.

There is no virtue in the promotion of mass death. Europe, with its leadership, will benefit from outside help and basic education. It would benefit even further from leadership that values the lives of its people.

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoRCMP Whistleblowers Accuse Members of Mark Carney’s Inner Circle of Security Breaches and Surveillance

-

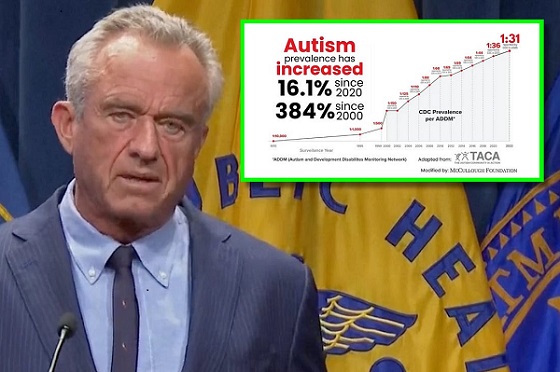

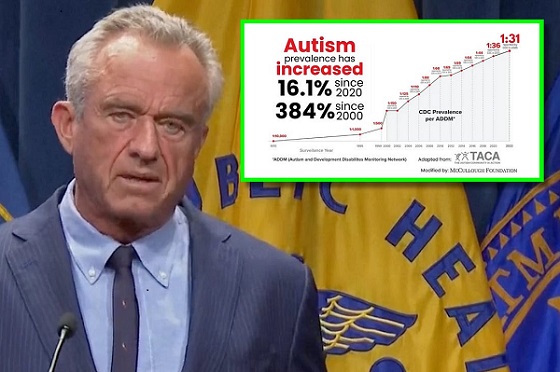

Autism2 days ago

Autism2 days agoAutism Rates Reach Unprecedented Highs: 1 in 12 Boys at Age 4 in California, 1 in 31 Nationally

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoTrump admin directs NIH to study ‘regret and detransition’ after chemical, surgical gender transitioning

-

Also Interesting1 day ago

Also Interesting1 day agoBetFury Review: Is It the Best Crypto Casino?

-

Autism1 day ago

Autism1 day agoRFK Jr. Exposes a Chilling New Autism Reality

-

Bjorn Lomborg2 days ago

Bjorn Lomborg2 days agoGlobal Warming Policies Hurt the Poor

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoCanadian student denied religious exemption for COVID jab takes tech school to court

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

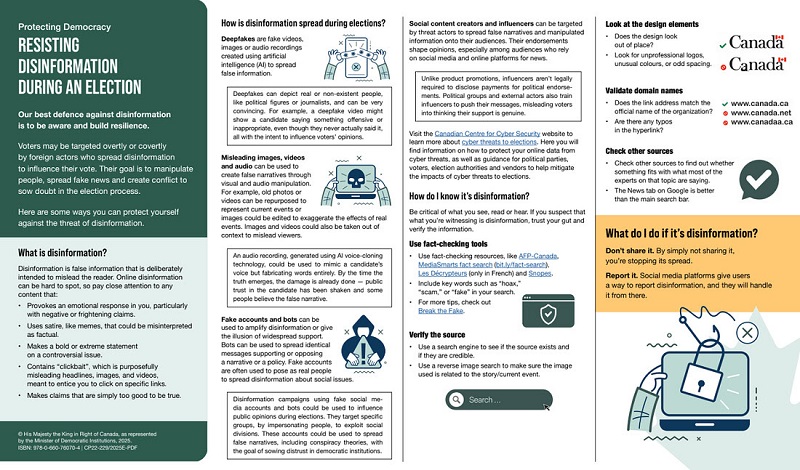

2025 Federal Election2 days agoAI-Driven Election Interference from China, Russia, and Iran Expected, Canadian Security Officials Warn