Indigenous

The Quiet Remaking of Canada

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

B.C. residents sat up and took notice of this shocking change when the Eby government announced that it planned to embark on a plan of “co-governance” with its indigenous population – a plan that would have given 5% of B.C.’s population a veto over every aspect of public land useage in the province.

Most Canadians are unaware that a campaign to remake Canada is underway. The conception of that most Canadians have of their country – that it is, one nation, in which citizens of different ethnic, religious and racial groups are all treated equally, under one set of laws – is being fundamentally transformed. B.C. residents sat up and took notice of this shocking change when the Eby government announced that it planned to embark on a plan of “co-governance” with its indigenous population – a plan that would have given 5% of B.C.’s population a veto over every aspect of public land useage in the province.

An emphatic “No” from an overwhelming majority of citizens put an end to this scheme – at least temporarily.

But the Eby government continues to move forward with its plan to transform the province into a multitude of semi-autonomous indigenous nations to accommodate that 5% of the indigenous B.C. population. It is proceeding with a plan that recognizes the Haida nation’s aboriginal title to the entire area of the traditional Haida territory. It would basically make Haida Gwaii into what would in essence be a semi-independent nation, ruled by Haida tribal law.

Many of us are familiar with that exceptionally beautiful part of Canada, where the Haida have lived for thousands of years. Misty Haida Gwaii, formerly known as the Queen Charlotte Islands, is a magical place. Until now, it has been a part of Canada. How would this Haida agreement change that?

Non-Haida residents of Haida Gwaii are probably asking themselves that question. Although they are being told that their fee simple ownership and other rights will not be affected by the Haida agreement, is that true? If one must be Haida by DNA to fully participate in decisions, how can it be argued that non Haida residents have rights equal to a Haida?

For example, the Supreme Court ruled in the Vuntut Gwitchin case that, based on the allegedly greater need of maintaining so-called Indigenous cultural “difference”, individual Indigenous Canadians can now be deprived by their band governments of their rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms on their home reserves and self-governing territories. Simply put, the law of the collective- namely tribal law- will apply.

So, tribal law takes precedence over Canadian law. And will a non-Haida resident be deprived of rights that he would enjoy anywhere else in Canada? For that matter, will an indigenous, but non-Haida, resident have equal rights to a Haida, if he can’t vote in Haida elections? Will this plan dilute, or even eliminate, fee simple ownership for some.

Or this: Does a provincial government even have the power to make such an agreement in the first place? After all Section 91(24) of our Constitution Act gives the federal government responsibility for status Indians.

These are but a few of the many questions that has B.C. residents asking many questions. In fact, the proposed Haida agreement will likely be front and centre in the upcoming provincial election, and could usher in decades of litigation and uncertainty.

But the Eby government has made it clear that the Haida agreement will be the template for others that will follow. Considering the fact that there are at least 200 separate indigenous communities in B.C. this would be a very ambitious undertaking – especially in light of the fact that most of those 200 or so communities are tiny, and almost all are dependent on taxpayers for their continued existence.

Eby is responding to the Supreme Court’s astounding decision that aboriginal title existed, unless it had been surrendered by treaty. The court relied on the Royal Proclamation of 1763 to come to this decision. This was after what was the longest trial in the history of B.C. wherein the trial judge in that case, Chief Justice Allan McEachern, had written a masterful decision finding that aboriginal title did not exist as claimed by the indigenous parties to the action. The Supreme Court went on in subsequent cases to transform Canadian indigenous law and expand section 35 in a manner that emphasized the need for “reconciliation”, the primacy of the collective over the rights of the individual for indigenous people, and the need for indigenous “nation to nation” separateness, instead of assimilation. All of this was done by judicial fiat, with absolutely no input from the Canadian public. Senior Ontario lawyer, Peter Best, describes this radical transformation of Canada in his epic work, “There Is No Difference”.

The unfortunate decision by both the federal government and the B.C. government to adopt UNDRIP, (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Aboriginal Peoples) and B.C.’s provincial version, DRIPA, (Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples) further muddied the waters.

What British Columbia will look like in 10 years is anyone’s guess, if the hundreds of indigenous communities in B.C. are successful in obtaining agreements similar to what the Haida negotiate. It also seems very likely that indigenous communities in other parts of Canada will see what the B.C. communities achieved, and want the same additional autonomy and land rights for themselves. In the treaty areas of Canada, namely mainly the prairies and parts of the north, the treaties, in theory, settle the issue. But, if the B.C. Indians succeed in obtaining superior entitlements, the treaty Indians will almost certainly agitate for “modern treaties” that include what the Haida received.

And the citizens of eastern Canada, who believe that their indigenous claims have been permanently settled long ago, are probably in for a rude shock. In “A New Look at Canadian Indian Policy” the late Gordon Gibson quotes a former senior bureaucrat in Indian Affairs who insisted on remaining anonymous. That source says bluntly that all of Canada will be at play if Canada does indeed become the “patchwork of tiny Bantustans” that journalist and visionary Jon Kay predicted in 2001, if we keep going down this “nation to nation” path.

In fact, it is quite possible that every one of the 600 or so indigenous communities in Canada will end up with at least as much “separateness” as the Haida obtained. Canada will be fundamentally transformed into a crazy quilt of mainly dependent reserves governed by tribal law. Surely the Fathers of Confederation didn’t work so hard to end up with such a backward, fractured Canada?

As we see this fundamental transformation taking place in B.C., and then heading eastward, I suspect that Canadians who do not want such a future for their country will start to ask themselves how we arrived at this point. How can a nation be fundamentally transformed with no input from the citizens? Don’t the Canadian people have to be consulted, as we watch our country being transformed by judicial fiat and tribal law? Doesn’t a constitutional process have to be invoked, as happened in the failed Meech Lake or Charlottetown Accords?

Most Canadians believe that history has not been kind to indigenous people, and that indigenous have legitimate claims that need to be addressed. But most Canadians also believe that Canada is one country, in which everyone should be equal.

Canadians also firmly believe that Canada should not be divided into racial enclaves, where different sets of laws are applied to different racial or ethnic groups. In fact, most Canadians would probably support the sub-title of the late Gordon Gibson book cited above: “Respect the Collective – Support the Individual”. Canadians want to see indigenous people succeed, and they support indigenous people in their fierce determination to hold on to their indigenous identity and culture. But they want indigenous people to succeed as Canadians – not in a Canada that has been carved up into racial ghettos, like slices of a cheap pizza.

The Haida agreement is the first highly visible slice – a symbol of a semi-independent “nation” within Canada, that will be governed by rights of the collective tribal law – as opposed to the rights of the individual. That takes us back thousands of years. Before the Haida agreement inspires hundreds of other such racial mini-states within Canada, should Canadians not have a say in what our country is becoming?

Or will we continue to let unelected judges, and faceless bureaucrats, determine our fate?

Brian Giesbrecht, retired judge, is a Senior Fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Canadian Energy Centre

Why nation-building Canadian resource projects need Indigenous ownership to succeed

Chief Greg Desjarlais of Frog Lake First Nation signs an agreement in September 2022 whereby 23 First Nations and Métis communities in Alberta will acquire an 11.57 per cent ownership interest in seven Enbridge-operated oil sands pipelines for approximately $1 billion. Photo courtesy Enbridge

From the Canadian Energy Centre

U.S. trade dispute converging with rising tide of Indigenous equity

A consensus is forming in Canada that Indigenous ownership will be key to large-scale, nation-building projects like oil and gas pipelines to diversify exports beyond the United States.

“Indigenous ownership benefits projects by making them more likely to happen and succeed,” said John Desjarlais, executive director of the Indigenous Resource Network.

“This is looked at as not just a means of reconciliation, a means of inclusion or a means of managing risk. I think we’re starting to realize this is really good business,” he said.

“It’s a completely different time than it was 10 years ago, even five years ago. Communities are much more informed, they’re much more engaged, they’re more able and ready to consider things like ownership and investment. That’s a very new thing at this scale.”

John Desjarlais, executive director of the Indigenous Resource Network in Bragg Creek, Alta. Photo by Dave Chidley for the Canadian Energy Centre

John Desjarlais, executive director of the Indigenous Resource Network in Bragg Creek, Alta. Photo by Dave Chidley for the Canadian Energy Centre

Canada’s ongoing trade dispute with the United States is converging with a rising tide of Indigenous ownership in resource projects.

“Canada is in a great position to lead, but we need policymakers to remove barriers in developing energy infrastructure. This means creating clear and predictable regulations and processes,” said Colin Gruending, Enbridge’s president of liquids pipelines.

“Indigenous involvement and investment in energy projects should be a major part of this strategy. We see great potential for deeper collaboration and support for government programs – like a more robust federal loan guarantee program – that help Indigenous communities participate in energy development.”

In a statement to the Canadian Energy Centre, the Alberta Indigenous Opportunities Corporation (AIOC) – which has backstopped more than 40 communities in energy project ownership agreements with a total value of over $725 million – highlighted the importance of seizing the moment:

“The time is now. Canada has a chance to rethink how we build and invest in infrastructure,” said AIOC CEO Chana Martineau.

“Indigenous partnerships are key to making true nation-building projects happen by ensuring critical infrastructure is built in a way that is competitive, inclusive and beneficial for all Canadians. Indigenous Nations are essential partners in the country’s economic future.”

Key to this will be provincial and federal programs such as loan guarantees to reduce the risk for Indigenous groups and industry participants.

“There are a number of instruments that would facilitate ownership that we’ve seen grow and develop…such as the loan guarantee programs, which provide affordable access to capital for communities to invest,” Desjarlais said.

Workers lay pipe during construction of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion on farmland in Abbotsford, B.C. on Wednesday, May 3, 2023. CP Images photo

Workers lay pipe during construction of the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion on farmland in Abbotsford, B.C. on Wednesday, May 3, 2023. CP Images photo

Outside Alberta, there are now Indigenous loan guarantee programs federally and in Saskatchewan. A program in British Columbia is in development.

The Indigenous Resource Network highlights a partnership between Enbridge and the Willow Lake Métis Nation that led to a land purchase of a nearby campground the band plans to turn into a tourist destination.

“Tourism provides an opportunity for Willow Lake to tell its story and the story of the Métis. That is as important to our elders as the economic considerations,” Willow Lake chief financial officer Michael Robert told the Canadian Energy Centre.

The AIOC reiterates the importance of Indigenous project ownership in a call to action for all parties:

“It is essential that Indigenous communities have access to large-scale capital to support this critical development. With the right financial tools, we can build a more resilient, self-sufficient and prosperous economy together. This cannot wait any longer.”

In an open letter to the leaders of all four federal political parties, the CEOs of 14 of Canada’s largest oil and gas producers and pipeline operators highlighted the need for the federal government to step up its participation in a changing public mood surrounding the construction of resource projects:

“The federal government needs to provide Indigenous loan guarantees at scale so industry may create infrastructure ownership opportunities to increase prosperity for communities and to ensure that Indigenous communities benefit from development,” they wrote.

For Desjarlais, it is critical that communities ultimately make their own decisions about resource project ownership.

“We absolutely have to respect that communities want to self-determine and choose how they want to invest, choose how they manage a lot of the risk and how they mitigate it. And, of course, how they pursue the rewards that come from major project investment,” he said.

Canadian Energy Centre

Saskatchewan Indigenous leaders urging need for access to natural gas

Piapot First Nation near Regina, Saskatchewan. Photo courtesy Piapot First Nation/Facebook

From the Canadian Energy Centre

By Cody Ciona and Deborah Jaremko

“Come to my nation and see how my people are living, and the struggles that they have day to day out here because of the high cost of energy, of electric heat and propane.”

Indigenous communities across Canada need access to natural gas to reduce energy poverty, says a new report by Energy for a Secure Future (ESF).

It’s a serious issue that needs to be addressed, say Indigenous community and business leaders in Saskatchewan.

“We’re here today to implore upon the federal government that we need the installation of natural gas and access to natural gas so that we can have safe and reliable service,” said Guy Lonechild, CEO of the Regina-based First Nations Power Authority, on a March 11 ESF webinar.

Last year, 20 Saskatchewan communities moved a resolution at the Assembly of First Nations’ annual general assembly calling on the federal government to “immediately enhance” First Nations financial supports for “more desirable energy security measures such as natural gas for home heating.”

“We’ve been calling it heat poverty because that’s what it really is…our families are finding that they have to either choose between buying groceries or heating their home,” Chief Christine Longjohn of Sturgeon Lake First Nation said in the ESF report.

“We should be able to live comfortably within our homes. We want to be just like every other homeowner that has that choice to be able to use natural gas.”

At least 333 First Nations communities across Canada are not connected to natural gas utilities, according to the Canada Energy Regulator (CER).

ESF says that while there are many federal programs that help cover the upfront costs of accessing electricity, primarily from renewable sources, there are no comparable ones to support natural gas access.

“Most Canadian and Indigenous communities support actions to address climate change. However, the policy priority of reducing fossil fuel use has had unintended consequences,” the ESF report said.

“Recent funding support has been directed not at improving reliability or affordability of the energy, but rather at sustainability.”

Natural gas costs less than half — or even a quarter — of electricity prices in Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, according to CER data.

“Natural gas is something NRCan [Natural Resources Canada] will not fund. It’s not considered a renewable for them,” said Chief Mark Fox of the Piapot First Nation, located about 50 kilometres northeast of Regina.

“Come to my nation and see how my people are living, and the struggles that they have day to day out here because of the high cost of energy, of electric heat and propane.”

According to ESF, some Indigenous communities compare the challenge of natural gas access to the multiyear effort to raise awareness and, ultimately funding, to address poor water quality and access on reserve.

“Natural gas is the new water,” Lonechild said.

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoNo Matter The Winner – My Canada Is Gone

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoASK YOURSELF! – Can Canada Endure, or Afford the Economic Stagnation of Carney’s Costly Climate Vision?

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoMade in Alberta! Province makes it easier to support local products with Buy Local program

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoCSIS Warned Beijing Would Brand Conservatives as Trumpian. Now Carney’s Campaign Is Doing It.

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoProvince to expand services provided by Alberta Sheriffs: New policing option for municipalities

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoInside Buttongate: How the Liberal Swamp Tried to Smear the Conservative Movement — and Got Exposed

-

Dr. Robert Malone1 day ago

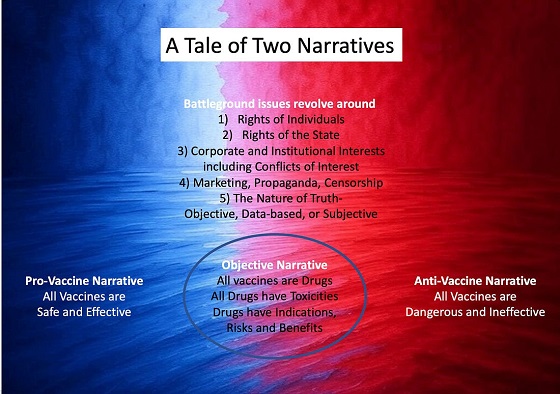

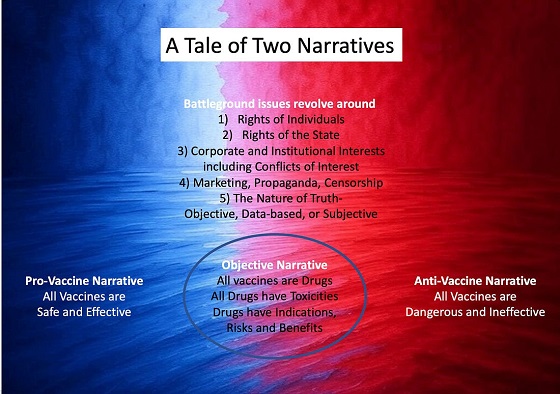

Dr. Robert Malone1 day agoThe West Texas Measles Outbreak as a Societal and Political Mirror

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoIs HNIC Ready For The Winnipeg Jets To Be Canada’s Heroes?