Health

The People Cheering Brian Thompson’s Murder Can’t Have the Medical Utopia That They Want

Whether private or public, third-party payment for health care is a huge problem.

Evoking a collective scream of despair from socialists and anti-corporate types, police in Pennsylvania arrested Luigi Mangione, a suspect in the murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. Thompson, they insist, stood in the way of the sort of health care they think they deserve and shooting him down on the street was some sort of bloody-minded strike for justice.

The assassin’s fans—and the legal system has yet to convict anybody for the crime—are moral degenerates. But they’re also dreaming, if they think insurance executives like Thompson are all that stands between them and their visions of a single-payer medical system that satisfies every desire. While there is a lot wrong with the main way health care is paid for and delivered in the U.S., what the haters want is probably not achievable, and the means many of them prefer would make things worse.

“Unlimited Care…Free of Charge”

“It is an old joke among health policy wonks that what the American people really want from health care reform is unlimited care, from the doctor of their choice, with no wait, free of charge,” Michael Tanner, then of the Cato Institute, quipped in 2017.

The problem, no matter how health care is delivered, is that it requires labor, time, and resources that are available in finite supply. Somebody must decide how to allocate medications, treatments, physicians, and hospital beds, and how to pay for it all. A common assumption in some circles is that Americans ration medicine by price, handing an advantage to the wealthy and sticking it to the poor.

“Today, as everyone knows, health care in the US can be prohibitively expensive even for people who have insurance,” Dylan Scott sniffed this week at Vox.

The alternative, supposedly, is one where health care is “universal,” with bills paid by government so everybody has access to care. Except, most Americans rely on somebody else to pay the bulk of their medical bills just like Canadians, Germans, and Britons. And while there are huge differences among the systems presented as alternatives to the one in the U.S., third-party payers—whether governments or insurance companies—do enormous damage to the provision of health care.

Third-Party Payers, Both Public and Private, Raise Costs

“Contrary to ‘conventional wisdom,’ health insurance—private or otherwise—does not make health care more affordable,” Jeffrey Singer, a surgeon and senior fellow with the Cato Institute, wrote in 2013. “The third party payment system is the principal force behind health care price inflation.”

In the U.S., the dominance of third-party payment, whether Thompson’s UnitedHealthcare, one of its competitors, Medicare, Medicaid, or something else, makes it difficult to know the price for procedures, medicines, and treatments—because there really isn’t one price when third-party payers are involved.

Several years ago, the first Trump administration required hospitals to publish prices for services. My local hospital offers an Excel spreadsheet with wildly varying prices for procedures and services, from different categories of self-pay, Medicare, Medicaid, and negotiated rates for competing insurance plans.

“A colonoscopy might cost you or your insurer a few hundred dollars—or several thousand, depending on which hospital or insurer you use,” NPR’s Julie Appleby pointed out in 2021.

That said, savvy patients paying their own bills can usually get a lower price than that paid by insurance.

“When government, lawyers, or third party insurance is responsible for paying the bills, consumers have no incentive to control costs,” Arthur Laffer, Donna Arduin, and Wayne Winegarden wrote in the 2009 paper, The Prognosis for National Health Insurance. After all, the premium or tax is already paid, right?

Other Countries Struggle With Similar Issues

Concerns about rising costs, demand, and finite resources apply just as much when the payer is the government.

“State health insurance patients are struggling to see their doctors towards the end of every quarter, while privately insured patients get easy access,” Germany’s Deutsche Welle reported in 2018. “The researchers traced the phenomenon to Germany’s ‘budget’ system, which means that state health insurance companies only reimburse the full cost of certain treatments up to a particular number of patients or a particular monetary value.” Budgeting is quarterly, and once it’s exhausted, that’s it.

Last year in the U.K., a Healthwatch report complained: “We’re seeing a two-tier system emerge, where healthcare is accessible only to those who can afford it, with one in seven people who responded to our poll advised to seek private care by NHS [National Health Service] staff.” Britain’s NHS remains popular, but it has long struggled with the demand and expense for cancer care and other expensive treatments.

And Canada’s single-payer system famously relies heavily on long wait times to ration care. “In 2023, physicians report a median wait time of 27.7 weeks between a referral from a general practitioner and receipt of treatment,” the Fraser Institute found last year. “This represents the longest delay in the survey’s history and is 198% longer than the 9.3 weeks Canadian patients could expect to wait in 1993.”

You have to wonder what those so furious at Brian Thompson that they would applaud his murder would say about the officials managing systems elsewhere. None of them deliver “unlimited care, from the doctor of their choice, with no wait, free of charge.” Some lack the minimal discipline imposed by what competition exists among insurers in the U.S.

We Need Less Government Involvement in Medicine

“Policymakers need to understand that the key to ‘affordable health care’ is not to increase the role of health insurance in peoples’ lives, but to diminish it,” Cato’s Singer concluded.

My family found that true when we contracted with a primary care practice that refuses insurance. We pay fixed annual fees, which includes exams, laboratory services, and some procedures. My doctor caught my atrial fibrillation when he walked me across his clinic hall on a hunch to run an EKG.

The Surgery Center of Oklahoma famously follows a similar model for much more than primary care. It publishes its prices, which don’t include the overhead and uncertainty of dealing with third-party payers.

Those examples point to a better health care system than what exists in the United States—or in most other countries, for that matter. They’re probably not the whole answer, because it’s unlikely that one approach will suit millions of people with different medical concerns, incomes, and preferences. But making people more, rather than less, responsible for their own health care, and getting government and other third-parties as far out of the matter as possible, is far better than cheering the murder of people who supposedly stand between us and an imaginary medical utopia.

|

|

|

armed forces

Yet another struggling soldier says Veteran Affairs Canada offered him euthanasia

From LifeSiteNews

‘It made me wonder, were they really there to help us, or slowly groom us to say ‘here’s a solution, just kill yourself.’

Yet another Canadian combat veteran has come forward to reveal that when he sought help, he was instead offered euthanasia.

David Baltzer, who served two tours in Afghanistan with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, revealed to the Toronto Sun that he was offered euthanasia on December 23, 2019—making him, as the Sun noted, “among the first Canadian soldiers offered therapeutic suicide by the federal government.”

Baltzer had been having a disagreement with his existing caseworker, when assisted suicide was brought up in in call with a different agent from Veteran Affairs Canada.

“It made me wonder, were they really there to help us, or slowly groom us to say ‘here’s a solution, just kill yourself,” Baltzer told the Sun.“I was in my lowest down point, it was just before Christmas. He says to me, ‘I would like to make a suggestion for you. Keep an open mind, think about it, you’ve tried all this and nothing seems to be working, but have you thought about medical-assisted suicide?’”

Baltzer was stunned. “It just seems to me that they just want us to be like ‘f–k this, I give up, this sucks, I’d rather just take my own life,’” he said. “That’s how I honestly felt.”

Baltzer, who is from St. Catharines, Ontario, joined up at age 17, and moved to Manitoba to join the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, one of Canada’s elite units. He headed to Afghanistan in 2006. The Sun noted that he “was among Canada’s first troops deployed to Afghanistan as part Operation Athena, where he served two tours and saw plenty of combat.”

“We went out on long-range patrols trying to find the Taliban, and that’s exactly what we did,” Baltzer said. “The best way I can describe it, it was like Black Hawk Down — all of the sudden the s–t hit the fan and I was like ‘wow, we’re fighting, who would have thought? Canada hasn’t fought like this since the Korean War.”

After returning from Afghanistan, Baltzer says he was offered counselling by Veteran Affairs Canada, but it “was of little help,” and he began to self-medicate for his trauma through substance abuse (he noted that he is, thankfully, doing well today). Baltzer’s story is part of a growing scandal. As the Sun reported:

A key figure shedding light on the VAC MAID scandal was CAF veteran Mark Meincke, whose trauma-recovery podcast Operation Tango Romeo broke the story. ‘Veterans, especially combat veterans, usually don’t reach out for help until like a year longer than they should’ve,’ Meincke said, telling the Sun he waited over two decades before seeking help.

‘We’re desperate by the time we put our hands up for help. Offering MAID is like throwing a cinderblock instead of a life preserver.’ Meincke said Baltzer’s story shoots down VAC’s assertions blaming one caseworker for offering MAID to veterans, and suggests the problem is far more serious than some rogue public servant.

‘It had to have been policy. because it’s just too many people in too many provinces,” Meincke told the Sun. “Every province has service agents from that province.’

Veterans Affairs Canada claimed in 2022 that between four and 20 veterans had been offered assisted suicide; Meincke “personally knows of five, and said the actual number’s likely close to 20.” In a previous investigation, VAC claimed that only one caseworker was responsible—at least for the four confirmed cases—and that the person “was lo longer employed with VAC.” Baltzer says VAC should have military vets as caseworkers, rather than civilians who can’t understand what vets have been through.

To date, no federal party leader has referenced Canada’s ongoing euthanasia scandals during the 2025 election campaign.

2025 Federal Election

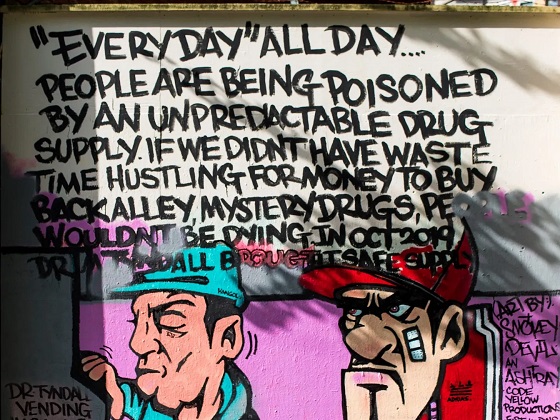

Study links B.C.’s drug policies to more overdoses, but researchers urge caution

By Alexandra Keeler

A study links B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization to more opioid hospitalizations, but experts note its limitations

A new study says B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization policies may have failed to reduce overdoses. Furthermore, the very policies designed to help drug users may have actually increased hospitalizations.

“Neither the safer opioid supply policy nor the decriminalization of drug possession appeared to mitigate the opioid crisis, and both were associated with an increase in opioid overdose hospitalizations,” the study says.

The study has sparked debate, with some pointing to it as proof that B.C.’s drug policies failed. Others have questioned the study’s methodology and conclusions.

“The question we want to know the answer to [but cannot] is how many opioid hospitalizations would have occurred had the policy not have been implemented,” said Michael Wallace, a biostatistician and associate professor at the University of Waterloo.

“We can never come up with truly definitive conclusions in cases such as this, no matter what data we have, short of being able to magically duplicate B.C.”

Jumping to conclusions

B.C.’s controversial safer supply policies provide drug users with prescription opioids as an alternative to toxic street drugs. Its decriminalization policy permitted drug users to possess otherwise illegal substances for personal use.

The peer-reviewed study was led by health economist Hai Nguyen and conducted by researchers from Memorial University in Newfoundland, the University of Manitoba and Weill Cornell Medicine, a medical school in New York City. It was published in the medical journal JAMA Health Forum on March 21.

The researchers used a statistical method to create a “synthetic” comparison group, since there is no ideal control group. The researchers then compared B.C. to other provinces to assess the impact of certain drug policies.

Examining data from 2016 to 2023, the study links B.C.’s safer supply policies to a 33 per cent rise in opioid hospitalizations.

The study says the province’s decriminalization policies further drove up hospitalizations by 58 per cent.

“Neither the safer supply policy nor the subsequent decriminalization of drug possession appeared to alleviate the opioid crisis,” the study concludes. “Instead, both were associated with an increase in opioid overdose hospitalizations.”

The B.C. government rolled back decriminalization in April 2024 in response to widespread concerns over public drug use. This February, the province also officially acknowledged that diversion of safer supply drugs does occur.

The study did not conclusively determine whether the increase in hospital visits was due to diverted safer supply opioids, the toxic illicit supply, or other factors.

“There was insufficient evidence to conclusively attribute an increase in opioid overdose deaths to these policy changes,” the study says.

Nguyen’s team had published an earlier, 2024 study in JAMA Internal Medicine that also linked safer supply to increased hospitalizations. However, it failed to control for key confounders such as employment rates and naloxone access. Their 2025 study better accounts for these variables using the synthetic comparison group method.

The study’s authors did not respond to Canadian Affairs’ requests for comment.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Correlation vs. causation

Chris Perlman, a health data and addiction expert at the University of Waterloo, says more studies are needed.

He believes the findings are weak, as they show correlation but not causation.

“The study provides a small signal that the rates of hospitalization have changed, but I wouldn’t conclude that it can be solely attributed to the safer supply and decrim[inalization] policy decisions,” said Perlman.

He also noted the rise in hospitalizations doesn’t necessarily mean more overdoses. Rather, more people may be reaching hospitals in time for treatment.

“Given that the [overdose] rate may have gone down, I wonder if we’re simply seeing an effect where more persons survive an overdose and actually receive treatment in hospital where they would have died in the pre-policy time period,” he said.

The Nguyen study acknowledges this possibility.

“The observed increase in opioid hospitalizations, without a corresponding increase in opioid deaths, may reflect greater willingness to seek medical assistance because decriminalization could reduce the stigma associated with drug use,” it says.

“However, it is also possible that reduced stigma and removal of criminal penalties facilitated the diversion of safer opioids, contributing to increased hospitalizations.”

Karen Urbanoski, an associate professor in the Public Health and Social Policy department at the University of Victoria, is more critical.

“The [study’s] findings do not warrant the conclusion that these policies are causally associated with increased hospitalization or overdose,” said Urbanoski, who also holds the Canada Research Chair in Substance Use, Addictions and Health Services.

Her team published a study in November 2023 that measured safer supply’s impact on mortality and acute care visits. It found safer supply opioids did reduce overdose deaths.

Critics, however, raised concerns that her study misrepresented its underlying data and showed no statistically significant reduction in deaths after accounting for confounding factors.

The Nguyen study differs from Urbanoski’s. While Urbanoski’s team focused on individual-level outcomes, the Nguyen study analyzed broader, population-level effects, including diversion.

Wallace, the biostatistician, agrees more individual-level data could strengthen analysis, but does not believe it undermines the study’s conclusions. Wallace thinks the researchers did their best with the available data they had.

“We do not have a ‘copy’ of B.C. where the policies weren’t implemented to compare with,” said Wallace.

B.C.’s overdose rate of 775 per 100,000 is well above the national average of 533.

Elenore Sturko, a Conservative MLA for Surrey-Cloverdale, has been a vocal critic of B.C.’s decriminalization and safer supply policies.

“If the government doesn’t want to believe this study, well then I invite them to do a similar study,” she told reporters on March 27.

“Show us the evidence that they have failed to show us since 2020,” she added, referring to the year B.C. implemented safer supply.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

-

2025 Federal Election10 hours ago

2025 Federal Election10 hours agoThe Federal Brief That Should Sink Carney

-

2025 Federal Election12 hours ago

2025 Federal Election12 hours agoHow Canada’s Mainstream Media Lost the Public Trust

-

2025 Federal Election15 hours ago

2025 Federal Election15 hours agoOttawa Confirms China interfering with 2025 federal election: Beijing Seeks to Block Joe Tay’s Election

-

2025 Federal Election14 hours ago

2025 Federal Election14 hours agoReal Homes vs. Modular Shoeboxes: The Housing Battle Between Poilievre and Carney

-

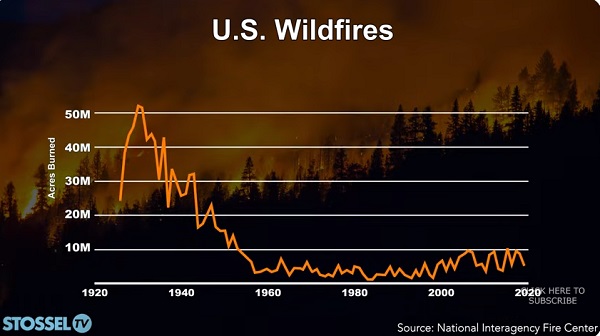

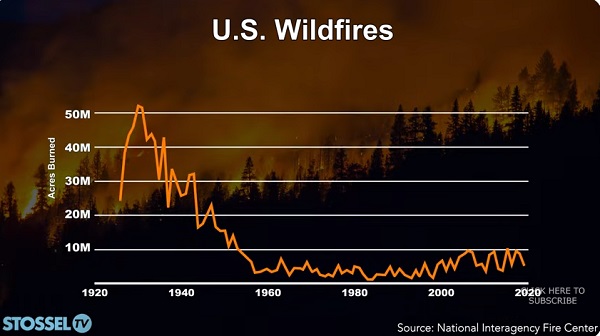

John Stossel11 hours ago

John Stossel11 hours agoClimate Change Myths Part 2: Wildfires, Drought, Rising Sea Level, and Coral Reefs

-

COVID-1913 hours ago

COVID-1913 hours agoNearly Half of “COVID-19 Deaths” Were Not Due to COVID-19 – Scientific Reports Journal

-

Entertainment2 days ago

Entertainment2 days agoPedro Pascal launches attack on J.K. Rowling over biological sex views

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoPoilievre Campaigning To Build A Canadian Economic Fortress