Opinion

The majority of voters have moved on from legacy media and legacy narratives

From EnergyNow.ca

By Margareta Dovgal

A Wake-Up Call for Political Strategists Across the Continent

For only the second time in US history, a president has lost, left office, and won re-election. For most Canadians watching the US election, the news of Donald Trump’s impending return to the White House comes with some degree of disappointment – and confusion.

Rather than getting caught up in doomsaying as there’s enough of that going around, I wanted to share some thoughts on what I would hope Canadians working in and around politics and policy come away with.

Speaking to the heart shouldn’t neglect speaking to the wallet

Biden probably should have resigned sooner, and Harris should have gone through a competitive primary race before carrying the flag. Hindsight is 20/20, and I doubt that the Democrats will make those same mistakes twice.

What I do suspect will be harder to shake is the commitment to running campaigns on social issues alone. The Democrats made the gamble that reproductive rights were a persuasive enough ballot box question to distract from Joe Biden’s lacklustre economic performance.

The clear majority of voters showed that they are more concerned with their job security, housing affordability, and tax bills.

The Democrats now have an opportunity to realign with the concerns of working Americans, recognizing that economic anxieties cannot be overlooked. A robust economic approach doesn’t preclude a moderate and fair social approach, but the latter can’t replace the former.

In Canada, this holds true for our discussions around energy and resources. I’m seeing a very similar disconnect play out on resource policy. Patently bad policies with horrible economic impacts are being advanced at all levels by governments more concerned with virtue signalling than ensuring robust economic performance – the federal Emissions Cap and the fantastical ambitions of David Eby’s CleanBC program among them.

Pre-pandemic, vibes-based economic policy seemed to work. In times of plenty, it is easy to persuade voters that taking economic hits is the right thing to do — after all, why worry about the price of something if you can afford it? Anyone still trying that in 2024 has lost the plot.

Affordability remains a paramount issue for many citizens, and the U.S. election highlighted how campaigns that overlook economic concerns and the declining quality of life risk alienating voters.

From groceries to gas prices, the rising cost of living is top of mind for Canadians, and resource policies must reflect this reality. For instance, a balanced approach to energy production can help keep costs reasonable while supporting Canadian jobs and industries.

It’s a reminder that beyond political credibility or mainstream appeal, policies that directly address financial challenges resonate most with the electorate.

For the resource sector, this means recognizing how affordable energy, resilient supply chains, and robust employment opportunities are interconnected with national policy priorities.

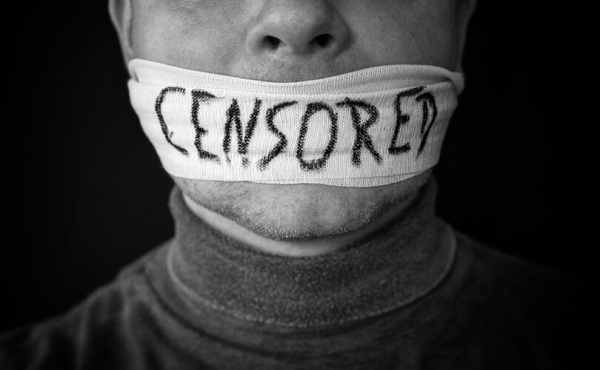

Truth and gatekeeping

The gamesmanship over who holds the authority to define “truth” continues in earnest, and engaging in it by discounting mass popular narratives is a risky gambit for any political movement that seeks to maintain widespread relevance.

We’re seeing a generational change, not just in the US but globally, on how people consume and produce media.

I would argue that Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter was the edge that Trump needed in this new era. Millions of Americans, and millions abroad, sought news and commentary from the platform. Political discourse on the 2024 election was shaped by the ideas generated and amplified online, faster than mainstream news could reliably pick up on.

Since Musk’s acquisition of Twitter/X, the editorial stance, algorithm, and tone of the platform have all shifted. Yes, it has gone ‘rightwards’, but rather than that serving to shrink the audience, it has instead grown, picking up swing voters and rallying the “persuadeds” more effectively.

Just look at the last debate between Trump and Harris: they weren’t even talking about the same political realities.

Research finds that as a main source of news, social media is still behind TV. Where we see the biggest difference is among younger voters.

46% of Americans 18-29 say social media is their top source of news, according to Pew Research. Beyond widespread appeal or readership, social media drives the political commentary of the chattering classes more than any one other platform. TikTok’s influence is likewise growing, with an even younger demographic relying on it almost entirely to help shape and articulate their views.

A similar dynamic around “truth” was plainly obvious in British Columbia’s provincial election last month. A good chunk of commentators couldn’t fathom that voters could accept a party that had refused to throw out candidates saying offensive or dubious things.

The BC Conservatives went from zero seats to just shy of government.

Enough ink has been spilled on this by other commentators, but let’s recap what many have said about the explanatory factors: BC United collapsed following its disastrous rebrand, the BC NDP was stuck with having to account with the inevitable baggage of incumbency in a struggling global economy, and the rise of Poilievre and the federal Conservatives lent some additional name-brand recognition to the BCCP.

The most important piece, in my estimation, was the Conservatives’ ability to tap into a growing demographic that didn’t feel their concerns were reflected in the mainstream political discourse. Twitter was far from the only forum for this, but I think it had a large part to play in cultivating the sense among many voters that consequential narratives were not even remotely being touched on in mainstream media. It gutted voters’ trust in the media, giving the BC Conservatives whose narratives were more effective on social media a decisive advantage.

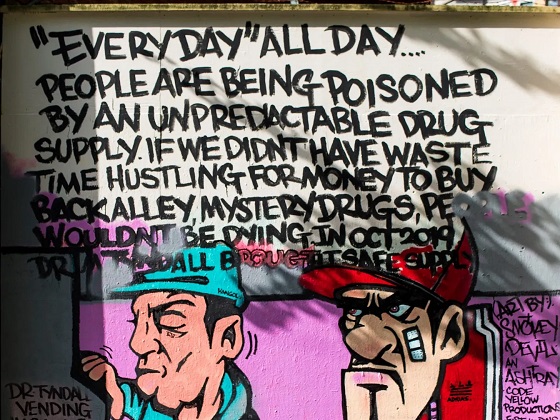

Public safety is a great example of this. Anyone with eyes and ears who has spent time in Downtown Vancouver in recent years can attest to the visible decline, with visible drug use in public spaces, frequent run-ins with people with severe untreated mental illness yelling at phantoms, and unabashed property crime.

Yet, if we were to believe a great deal of commentators just up until the eve of the election, everything was just fine.

Willful blindness only works when people can’t comment on what they see. But comment they did, and the delayed response to it nearly cost the BC NDP the election.

In a purely practical sense, the increasing role of community-driven sources of information mean that gatekeepers can no longer control the flow of information. And let’s not mince words here: anyone concerned about misinformation is talking about gatekeeping.

Subjecting ideas out there in the commons to scrutiny is necessary. We just can’t take for granted that the outlets themselves will provide that editorial scrutiny directly, if it’s not baked in the platform by design and people are actively choosing to spend time on platforms that have a radical free speech mandate.

It’s time to accept that the train has left the station: persuasiveness needs to be redefined by the mainstream, rather than taking one loss after another and crying foul because the game has changed.

Canadian narratives for Canadian politics

Our closest neighbour and trading partner is the world’s largest economy, and Canadians can’t help but look south for news and ideas. Our own politics often mirror the messages we see in the US, and there’s no use trying to pretend that won’t keep happening.

If we want to avoid falling into the trap of inheriting the dysfunction and divisions that are increasingly defining the political system next door, we have a duty to develop compelling narratives that resonate with the unique needs of Canadians, across the political spectrum.

It’s the definition of insanity to keep trying the same things expecting a different result. Rather than directing anger at voters and political movements who have moved on from old media, if you’re not happy with the result, try meeting them where they are.

And no, this doesn’t mean ceding ground to conspiracy theorists or the fringe. They are only succeeding because a) they are speaking to issues that people decide they care about (like them or not) that are panned by the center and the left, and b) most crucially, there isn’t enough emotionally resonant, persuasive substance being put out to win hearts and minds.

These are not inevitable outcomes. Voter preferences and media technologies are constantly evolving. We need to evolve with them by subjecting our leaders to real scrutiny and demanding better.

Margareta Dovgal is Managing Director of Resource Works. Based in Vancouver, she holds a Master of Public Administration in Energy, Technology and Climate Policy from University College London. Beyond her regular advocacy on natural resources, environment, and economic policy, Margareta also leads our annual Indigenous Partnerships Success Showcase. She can be found on Twitter and LinkedIn.

2025 Federal Election

The Cost of Underselling Canadian Oil and Gas to the USA

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Canadians can now track in real time how much revenue the country is forfeiting to the United States by selling its oil at discounted prices, thanks to a new online tracker from the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. The tracker shows the billions in revenue lost due to limited access to distribution for Canadian oil.

At a time of economic troubles and commercial tensions with the United States, selling our oil at a discount to U.S. middlemen who then sell it in the open markets at full price will rob Canada of nearly $19 billion this year, said Marco Navarro-Genie, the VP of Research at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Navarro-Genie led the team that designed the counter.

The gap between world market prices and what Canada receives is due to the lack of Canadian infrastructure.

According to a recent analysis by Ian Madsen, senior policy analyst at the Frontier Centre, the lack of international export options forces Canadian producers to accept prices far below the world average. Each day this continues, the country loses hundreds of millions in potential revenue. This is a problem with a straightforward remedy, said David Leis, the Centre’s President. More pipelines need to be approved and built.

While the Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) pipeline has helped, more is needed. It commenced commercial operations on May 1, 2024, nearly tripling Canada’s oil export capacity westward from 300,000 to 890,000 barrels daily. This expansion gives Canadian oil producers access to broader global markets, including Asia and the U.S. West Coast, potentially reducing the price discount on Canadian crude.

This is more than an oil story. While our oil price differential has long been recognized, there’s growing urgency around our natural gas exports. The global demand for cleaner energy, including Canadian natural gas, is climbing. Canada exports an average of 12.3 million GJ of gas daily. Yet, we can still not get the full value due to infrastructure bottlenecks, with losses of over $7.3 billion (2024). A dedicated counter reflecting these mounting gas losses underscores how critical this issue is.

“The losses are not theoretical numbers,” said Madsen. “This is real money, and Canadians can now see it slipping away, second by second.”

The Frontier Centre urges policymakers and industry leaders to recognize the economic urgency and ensure that infrastructure projects like TMX are fully supported and efficiently utilized to maximize Canada’s oil export potential. The webpage hosting the counter offers several examples of what the lost revenue could buy for Canadians. A similar counter for gas revenue lost through similarly discounted gas exports will be added in the coming days.

What Could Canada Do With $25.6 Billion a Year?

Without greater pipeline capacity, Canada loses an estimated (2025) $25.6 billion by selling our oil and gas to the U.S. at a steep discount. That money could be used in our communities — funding national defence, hiring nurses, supporting seniors, building schools, and improving infrastructure. Here’s what we’re giving up by underselling these natural resources.

342,000 Nurses

The average annual salary for a registered nurse in Canada is about $74,958. These funds could address staffing shortages and improve patient care nationwide.

Source

39,000 New Housing Units

At an estimated $472,000 per unit (excluding land costs, based on Toronto averages), $25.6 billion could fund nearly 94,000 affordable housing units.

Source

About the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

The Frontier Centre for Public Policy is an independent Canadian think-tank that researches and analyzes public policy issues, including energy, economics and governance.

Automotive

Hyundai moves SUV production to U.S.

MxM News

MxM News

Quick Hit:

Hyundai is responding swiftly to 47th President Donald Trump’s newly implemented auto tariffs by shifting key vehicle production from Mexico to the U.S. The automaker, heavily reliant on the American market, has formed a specialized task force and committed billions to American manufacturing, highlighting how Trump’s America First economic policies are already impacting global business decisions.

Key Details:

-

Hyundai has created a tariffs task force and is relocating Tucson SUV production from Mexico to Alabama.

-

Despite a 25% tariff on car imports that began April 3, Hyundai reported a 2% gain in Q1 operating profit and maintained earnings guidance.

-

Hyundai and Kia derive one-third of their global sales from the U.S., where two-thirds of their vehicles are imported.

Diving Deeper:

In a direct response to President Trump’s decisive new tariffs on imported automobiles, Hyundai announced Thursday it has mobilized a specialized task force to mitigate the financial impact of the new trade policy and confirmed production shifts of one of its top-selling models to the United States. The move underscores the gravity of the new 25% import tax and the economic leverage wielded by a White House that is now unambiguously prioritizing American industry.

Starting with its popular Tucson SUV, Hyundai is transitioning some manufacturing from Mexico to its Alabama facility. Additional consideration is being given to relocating production away from Seoul for other U.S.-bound vehicles, signaling that the company is bracing for the long-term implications of Trump’s tariffs.

This move comes as the 25% import tax on vehicles went into effect April 3, with a matching tariff on auto parts scheduled to hit May 3. Hyundai, which generates a full third of its global revenue from American consumers, knows it can’t afford to delay action. Notably, U.S. retail sales for Hyundai jumped 11% last quarter, as car buyers rushed to purchase vehicles before prices inevitably climb due to the tariff.

Despite the trade policy, Hyundai reported a 2% uptick in first-quarter operating profit and reaffirmed its earnings projections, indicating confidence in its ability to adapt. Yet the company isn’t taking chances. Ahead of the tariffs, Hyundai stockpiled over three months of inventory in U.S. markets, hoping to blunt the initial shock of the increased import costs.

In a significant show of good faith and commitment to U.S. manufacturing, Hyundai last month pledged a massive $21 billion investment into its new Georgia plant. That announcement was made during a visit to the White House, just days before President Trump unveiled the auto tariff policy — a strategic alignment with a pro-growth, pro-America agenda.

Still, the challenges are substantial. The global auto industry depends on complex, multi-country supply chains, and analysts warn that tariffs will force production costs higher. Hyundai is holding the line on pricing for now, promising to keep current model prices stable through June 2. After that, however, price adjustments are on the table, potentially passing the burden to consumers.

South Korea, which remains one of the largest exporters of automobiles to the U.S., is not standing idle. A South Korean delegation is scheduled to meet with U.S. trade officials in Washington Thursday, marking the start of negotiations that could redefine the two nations’ trade dynamics.

President Trump’s actions represent a sharp pivot from the era of global corporatism that defined trade under the Obama-Biden administration. Hyundai’s swift response proves that when the U.S. government puts its market power to work, foreign companies will move mountains — or at least entire assembly lines — to stay in the game.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoChinese firm unveils palm-based biometric ID payments, sparking fresh privacy concerns

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoConservatives promise to ban firing of Canadian federal workers based on COVID jab status

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoIs Government Inflation Reporting Accurate?

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoCarney’s Hidden Climate Finance Agenda

-

Environment2 days ago

Environment2 days agoExperiments to dim sunlight will soon be approved by UK government: report

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoStudy links B.C.’s drug policies to more overdoses, but researchers urge caution

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoIs free speech over in the UK? Government censorship reaches frightening new levels

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoPope Francis Got Canadian History Wrong