David Clinton

The Hidden and Tragic Costs of Housing and Immigration Policies

We’ve discussed the housing crisis before. That would include the destabilizing combination of housing availability – in particular a weak supply of new construction – and the immigration-driven population growth.

Parsing all the data can be fun, but we shouldn’t forget the human costs of the crisis. There’s the significant financial strain caused by rising ownership and rental costs, the stress so many experience when desperately searching for somewhere decent to live, and the pressure on businesses struggling to pay workers enough to survive in madly expensive cities.

If Canada doesn’t have the resources to house Canadians, should there be fewer of us?

Well we’ve also discussed the real problems caused by low fertility rates. As they’ve already discovered in low-immigration countries like Japan and South Korea, there’s the issue of who will care for the growing numbers of childless elderly. And who – as working-age populations sharply decline – will sign up for the jobs that are necessary to keep things running.

How much are the insights you discover in The Audit worth to you?

Consider becoming a paid subscriber.

The odds are that we’re only a decade or so behind Japan. Remember how a population’s replacement-level fertility rate is around 2.1 percent? Here’s how Canadian “fertility rates per female” have dropped since 1991:

Put differently, Canada’s crude birth rate per 1,000 population dropped from 14.4 in 1991, to 8.8 in 2023.

As a nation, we face very difficult constraints.

But there’s another cost to our problems that’s both powerful and personal, and it exists at a place that overlaps both crises. A recent analysis by the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) frames it in terms of suppressed household formation.

Household formation happens when two more more people choose to share a home. As I’ve written previously, there are enormous economic benefits to such arrangements, and the more permanent and stable the better. There’s also plenty of evidence that children raised within stable families have statistically improved economic, educational, and social outcomes.

But if households can’t form, there won’t be a lot of children.

In fact, the PBO projects that population and housing availability numbers point to the suppression of nearly a half a million households in 2030. And that’s incorporating the government’s optimistic assumptions about their new Immigration Levels Plan (ILP) to reduce targets for both permanent and temporary residents. It also assumes that all 2.8 million non-permanent residents will leave the country when their visas expire. Things will be much worse if either of those assumptions doesn’t work out according to plan.

Think about a half a million suppressed households. That number represents the dreams and life’s goals of at least a million people. Hundreds of thousands of 30-somethings still living in their parents basements. Hundreds of thousands of stable, successful, and socially integrated families that will never exist.

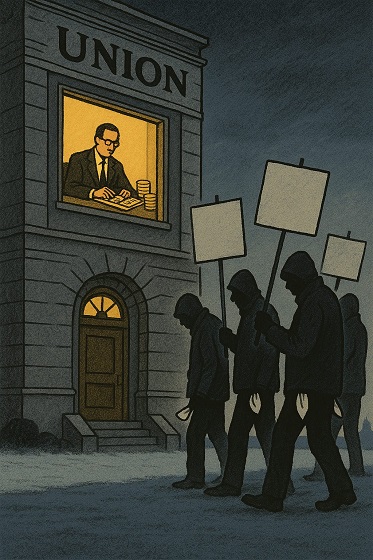

And all that will be largely (although not exclusively) the result of dumb-as-dirt political decisions.

Who says policy doesn’t matter?

How much are the insights you discover in The Audit worth to you?

Consider becoming a paid subscriber.

For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

Artificial Intelligence

When A.I. Investments Make (No) Sense

Based mostly on their 2024 budget, the federal government has promised $2.4 billion in support of artificial intelligence (A.I.) innovation and research. Given the potential importance of the A.I. sector and the universal expectation that modern governments should support private business development, this doesn’t sound all that crazy.

But does this particular implementation of that role actually make sense? After all, the global A.I. industry is currently suffering existential convulsions, with hundreds of billions of dollars worth of sector dominance regularly shifting back and forth between the big corporate players. And I’m not sure any major provider has yet built a demonstrably profitable model. Is Canada in a realistic position to compete on this playing field and, if we are, should we really want to?

First of all, it’s worth examining the planned spending itself.

- $2 billion over five years was committed to the Canadian Sovereign A.I. Compute Strategy, which targets public and private infrastructure for increasing A.I. compute capacity, including public supercomputing facilities.

- $200 million has been earmarked for the Regional Artificial Intelligence Initiative (RAII) via Regional Development Agencies intended to boost A.I. startups.

- $100 million to boost productivity is going to the National Research Council Canada’s A.I. Assist Program

- The Canadian A.I. Safety Institute will receive $50 million

In their goals, the $300 million going to those RAII and NRC programs don’t seem substantially different from existing industry support programs like SR&ED. So there’s really nothing much to say about them.

And I wish the poor folk at the Canadian A.I. Safety Institute the best of luck. Their goals might (or might not) be laudable, but I personally don’t see any chance they’ll be successful. Once A.I. models come on line, it’s only a matter of time before users will figure out how to make them do whatever they want.

But I’m really interested in that $2 billion for infrastructure and compute capacity. The first red flag here has to be our access to sufficient power generation.

Canada currently generates more electrical power than we need, but that’s changing fast. To increase capacity to meet government EV mandates, decarbonization goals, and population growth could require doubling our capacity. And that’s before we try to bring A.I. super computers online. Just for context, Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Oracle all have plans to build their own nuclear reactors to power their data centers. These things require an enormous amount of power.

I’m not sure I see a path to success here. Plowing money into A.I. compute infrastructure while promoting zero emissions policies that’ll ensure your infrastructure can never be powered isn’t smart.

However, the larger problem here may be the current state of the A.I. industry itself. All the frantic scrambling we’re seeing among investors and governments desperate to buy into the current gold rush is mostly focused on the astronomical investment returns that are possible.

There’s nothing wrong with that in principle. But “astronomical investment returns” are also possible by betting on extreme long shots at the race track or shorting equity positions in the Big Five Canadian banks. Not every “possible” investment is appropriate for government policymakers.

Right now the big players (OpenAI, Anthropic, etc.) are struggling to turn a profit. Sure, they regularly manage to build new models that drop the cost of an inference token by ten times. But those new models consume ten or a hundred times more tokens responding to each request. And flat-rate monthly customers regularly increase the volume and complexity of their requests. At this point, there’s apparently no easy way out of this trap.

Since business customers and power users – the most profitable parts of the market – insist on using only the newest and most powerful models while resisting pay-as-you-go contracts, profit margins aren’t scaling. Reportedly, OpenAI is betting on commoditizing its chat services and making its money from advertising. But it’s also working to drive Anthropic and the others out of business by competing head-to-head for the enterprise API business with low prices.

In other words, this is a highly volatile and competitive industry where it’s nearly impossible to visualize what success might even look like with confidence.

Is A.I. potentially world-changing? Yes it is. Could building A.I. compute infrastructure make some investors wildly wealthy? Yes it could. But is it the kind of gamble that’s suitable for public funds?

Perhaps not.

Business

Is Canada’s $100B+ Climate Plan Based on Shaky Science?

Rising CO2 levels have, in fact, been instrumental in promoting an ongoing planet-wide increase in vegetation cover. This is thanks to enhanced photosynthesis and water use efficiency and has contributed to higher agricultural yields. It turns out that, whatever acidification may be happening, there appears to be no serious impact on marine life.

The Climate Working Group at the U.S. Department of Energy recently published “A Critical Review of Impacts of Greenhouse Gas Emissions on the U.S. Climate“. Of note, that group includes University of Guelph’s very own Professor Ross McKitrick.

The authors conclude that while climate change is real and influenced by human emissions, its risks are often exaggerated. Instead:

- Published models have consistently and aggressively overestimated warming

- Extreme weather trends are not worsening as claimed

- Aggressive mitigation policies may cause more harm than good

Rising CO2 levels have, in fact, been instrumental in promoting an ongoing planet-wide increase in vegetation cover. This is thanks to enhanced photosynthesis and water use efficiency and has contributed to higher agricultural yields. It turns out that, whatever acidification may be happening, there appears to be no serious impact on marine life.

To be sure, there’s been vocal push back against the report’s findings. But that just highlights the complexity, volatility, and intense political stakes of the issues involved.

Despite my own stellar academic publishing history (see my high school paper from 45 years ago on CO2 emissions and the acidification of lakes in Ontario for full details), it turns out that I’m not qualified to express an opinion here. After all, I lack the necessary combined expertise in natural sciences, applied sciences, social sciences, and so on.

But I suspect that the people in Ottawa who make related policy decisions aren’t necessarily all that better prepared than I am. Which makes me wonder just how much of our money has been spent through the past ten years based on assumptions that are far from universally accepted in the scientific community.

The short answer is: many billions of dollars. Here are some highlights:

- $28.7 billion for the public transit envelope from the Investing in Canada Plan

- $26.9 billion for the Green Infrastructure Investments envelope from the Investing in Canada Plan

- $2 billion for the Low Carbon Economy Fund

- $8 billion for the Net Zero Accelerator

- $103 billion for the Clean-economy Investment Tax Credits (although that won’t all be spent before 2035)

- $3 billion in EV purchase rebates from the Incentives for Zero-Emission Vehicles

- $2.6 billion for Canada Greener Homes Grants

- $2.75 billion for the Zero-Emission Transit Fund (school buses and municipal ZEV fleets)

- $1.5 billion to support low-carbon fuel production and adoption

- $964 million for the Smart Renewables and Electrification Pathways Program (renewable projects, storage, and grid modernization)

- $680 million for Zero-Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Program (charging stations and hydrogen refuelling)

Granted, some of that funding will address other policy needs besides just climate change mitigation, and nearly all of it is designed to be paid out over multiple years. And of course, not all funds that were allocated have been spent yet. Two thumbs up for inertia!

But it’s still an awful lot of money considering no one really knows for sure whether any of this is helpful. Not to mention that, while it’s complicated, after a decade of trying, Canada’s actual emissions haven’t necessarily dropped.

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoDemocrats Explicitly Tell Spy Agencies, Military To Disobey Trump

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoNearly One-Quarter of Consumer-Goods Firms Preparing to Exit Canada, Industry CEO Warns Parliament

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCarney bets on LNG, Alberta doubles down on oil

-

Indigenous2 days ago

Indigenous2 days agoTop constitutional lawyer slams Indigenous land ruling as threat to Canadian property rights

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta on right path to better health care

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta Emergency Alert test – Wednesday at 1:55 PM

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoALAN DERSHOWITZ: Can Trump Legally Send Troops Into Our Cities? The Answer Is ‘Wishy-Washy’

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoCarney government’s anti-oil sentiment no longer in doubt