Food

RFK Jr.’s War on Toxic Baby Formula and Junk Food Begins

Long-needed reforms start now.

The following is an editorialized version of a thread that originally appeared on the American Values X page. It was republished and edited with permission. Click here to read the original thread.

For the first time in over two decades, baby formula in the U.S. is getting a serious safety overhaul. On Thursday, Secretary Kennedy announced, alongside HHS and the FDA, “Operation Stork Speed,” a major initiative aimed at improving the safety and nutritional quality of infant formula.

“We’re gonna review the formulations for the first time since 1998 and do comprehensive tests to make sure this is the healthiest product that our kids can have,” Kennedy announced.

But that’s just the beginning. Kennedy is also taking on the growing concerns around cell phone use in schools—something he says is hurting kids on multiple levels.

“There are many other countries in the world that have banned cell phones in our schools.”

“Cell phones also produce electric magnetic radiation, which has been shown to do neurological damage to kids when it’s around them all day.”

“Cell phone use and social media use on the cell phone has been directly connected with depression, poor performance in schools, suicidal ideation, and with substance abuse.”

Kennedy is also tackling what he sees as one of the biggest flaws in how America approves food ingredients. He’s targeting the GRAS (“Generally Recognized As Safe”) loophole that’s allowed questionable substances to enter our food supply for years.

“We are going to get rid of the GRAS standards for new products. We’re going to go back and review all of these old ingredients to make sure that they are safe, and we’re going to encourage these companies to get rid of them as quickly as possible,” Kennedy said.

And when it comes to food safety, Kennedy says it’s time for the U.S. to catch up with the rest of the world.

“In this country, food ingredients are innocent till proven guilty.”

“In Europe and other countries they have to prove themselves safe before you add them, and we ought to have that kind of protection for American citizens.”

It’s a refreshing sight to see Secretary Kennedy take a wrecking ball to the status quo. From cracking down on harmful ingredients in baby formula to general food safety, he’s sending a clear message that the health and safety of America’s children come first.

Thanks for reading.

If you value the work being published here, upgrading your subscription is the most powerful way to support it.

The more this Substack earns, the more we can expand the team, improve quality,

and create the best reader experience possible.

Alberta

Made in Alberta! Province makes it easier to support local products with Buy Local program

Show your Alberta side. Buy Local. |

When the going gets tough, Albertans stick together. That’s why Alberta’s government is launching a new campaign to benefit hard-working Albertans.

Global uncertainty is threatening the livelihoods of hard-working Alberta farmers, ranchers, processors and their families. The ‘Buy Local’ campaign, recently launched by Alberta’s government, encourages consumers to eat, drink and buy local to show our unified support for the province’s agriculture and food industry.

The government’s ‘Buy Local’ campaign encourages consumers to buy products from Alberta’s hard-working farmers, ranchers and food processors that produce safe, nutritious food for Albertans, Canadians and the world.

“It’s time to let these hard-working Albertans know we have their back. Now, more than ever, we need to shop local and buy made-in-Alberta products. The next time you are grocery shopping or go out for dinner or a drink with your friends or family, support local to demonstrate your Alberta pride. We are pleased tariffs don’t impact the ag industry right now and will keep advocating for our ag industry.”

Alberta’s government supports consumer choice. We are providing tools to help folks easily identify Alberta- and Canadian-made foods and products. Choosing local products keeps Albertans’ hard-earned dollars in our province. Whether it is farm-fresh vegetables, potatoes, honey, craft beer, frozen food or our world-renowned beef, Alberta has an abundance of fresh foods produced right on our doorstep.

Quick facts

- This summer, Albertans can support local at more than 150 farmers’ markets across the province and meet the folks who make, bake and grow our food.

- In March 2023, the Alberta government launched the ‘Made in Alberta’ voluntary food and beverage labelling program to support local agriculture and food sectors.

- Through direct connections with processors, the program has created the momentum to continue expanding consumer awareness about the ‘Made in Alberta’ label to help shoppers quickly identify foods and beverages produced in our province.

- Made in Alberta product catalogue website

Related information

Bjorn Lomborg

Climate change isn’t causing hunger

From the Fraser Institute

Surprisingly, a green, low-carbon world produces less and more expensive food, and makes over 50 million more people hungry by mid-century.

Food scarcity affects many people around the world. Canada can help, as the world’s fifth largest exporter of agricultural goods and the fourth largest exporter of wheat. Indeed, Canada exports so much food that measured in calories it can feed more than 180 million people.

We hear often that carbon cuts are a priority because climate change is causing world hunger and that even Canada will be hit by higher prices and less choice. These alarmist claims are far from true, and the recommended policies are counterproductive.

Over the past century, hunger has dramatically declined. In 1928, the League of Nations estimated that more than two-thirds of humanity lived in a constant state of hunger. By 1970, malnutrition afflicted just one-quarter of all people. Since 2008, the world has seen less than one-in-ten of all people go hungry, although Covid and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have increased the percentage from a low of just over 7 per cent to 9 per cent in 2023.

This positive trend is because humanity has become much better at producing food, and incomes have risen dramatically. For instance, we have more than quintupled cereal production since 1926, and more than halved global food prices. At the same time, extreme poverty has dropped precipitously, allowing parents to afford to buy their children more and better food.

There is obviously still more to do, but securing food for the vast majority of the world has been an unmitigated success in the human development story.

As we move towards 2050, it is likely incomes will keep increasing, with extreme poverty almost disappearing. At the same time, food prices will likely slightly decline or stay about the same, as even more people switch to higher-quality and more expensive foods. All credible predictions foresee even lower levels of malnutrition by mid-century.

The impact of climate change on food supply is often portrayed as terrible, but in reality, it means that things will get much better slightly slower. It will change conditions for most farmers, making conditions better for some and worse for others. In total, it is likely the net outcome will be worse, but only slightly so. One peer-reviewed estimate shows the climate impact on agriculture is equivalent to reducing global GDP by the end of the century by less than 0.06 per cent.

CO₂ is a plant fertilizer, as is well-known by enterprising tomato producers, who routinely pump CO₂ into their greenhouses to boost productivity. We see a similar impact across the living world. Since the 1970s, the increasing CO₂ concentration has caused the planet to become greener, producing more biomass. Satellites show that since 2000, the world has gotten so many more green leaves that their total area is larger than the entire area of Australia.

In total, models show that without climate change, the global amount of food, measured in calories, produced in 2050 will likely increase 51 per cent from 2010. Even under extreme, unrealistic climate change, it will increase 49 per cent. Across all models and scenarios, the difference in calories per person is one-tenth of a percent.

The graph shows how many children died each year from malnutrition from 1990 to 2021, with the World Health Organization estimating the impact of climate change up to 2050. Since 1990, the average number of children dying has declined dramatically from 6.5 million to 2.5 million each year. This is an incredible success story.

The WHO expects the decline to continue, with annual deaths halving once again. But in a world with climate change, deaths will still decline but slightly more slowly. Unfortunately, the lower death decline in 2050 created almost all the media headlines from the WHO study, entirely ignoring the dramatic reduction in overall death.

The overarching response from climate campaigners is to demand radical emission cuts to help. But this ignores two important facts. First, trying to affect change through climate policy is the slowest, costliest and least impactful way to help. While even significant climate policy will take over half a century to have any measurable impact and cost hundreds of trillions, it will at best help increase available calories by less than one-tenth of a percentage point. Instead, a focus on increased economic growth is over one hundred times more effective, increasing calorie availability by over 10 per cent. Moreover, it would work in years instead of centuries, and deliver a host of other, obvious benefits.

Second, cutting emissions increases most agricultural costs, like pushing up prices for fertilizer and gas for tractors, along with increased competition for land for biofuels and reforestation. Uselessly, most models just ignore these costs — like the WHO simply imagining a world without climate change. But it turns out that the impact of cutting emissions harms food production much more than climate change does. Surprisingly, a green, low-carbon world produces less and more expensive food, and makes over 50 million more people hungry by mid-century.

While we are being told stories of climate agricultural catastrophes and urged to cut emissions dramatically, the evidence shows that the impact is tiny, making the world improve slightly less fast. The proposed cure is worse than the problem it seeks to fix.

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoMassive new study links COVID jabs to higher risk of myocarditis, stroke, artery disease

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoConservative Party urges investigation into Carney plan to spend $1 billion on heat pumps

-

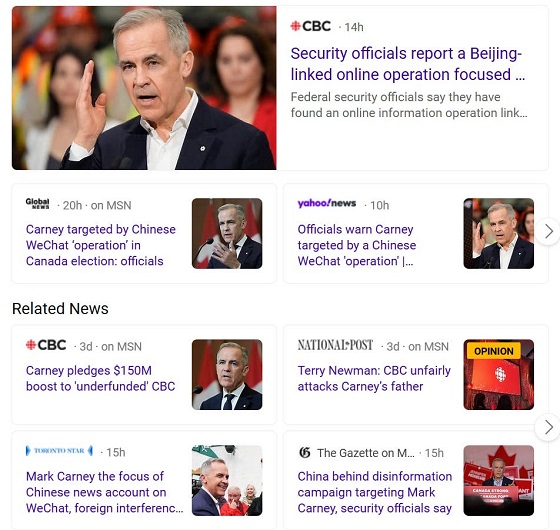

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoCommunist China helped boost Mark Carney’s image on social media, election watchdog reports

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoFifty Shades of Mark Carney

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta’s embrace of activity-based funding is great news for patients

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoDon’t double-down on net zero again

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoExpert Medical Record Reviews Of The Two Girls In Texas Who Purportedly Died of Measles

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoCorporate Media Isn’t Reporting on Foreign Interference—It’s Covering for It