Health

Red Deer Regional Health Foundation scholarships help kick start health care careers

Health Foundation awards $86,500 in scholarships

25 individuals receive scholarships

Thanks to the generosity of Central Alberta donors, the Red Deer Regional Health Foundation is providing educational scholarships totalling $86,500 in 2023.

The scholarship recipients are students enrolled in various healthcare programs, including cardiology, respiratory health medicine, hospice palliative care, nursing, and pediatrics. These scholarships help ensure that excellent healthcare professionals are available to provide for the future needs of Central Albertans. Among the criteria used to select successful candidates is the requirement they must live in or have their permanent

residence within 100 kilometers of Red Deer.

“The Foundation is fortunate to have donors who support superior care for Central Albertans and those who endeavor to work in the healthcare field,” says Manon Therriault, Foundation CEO.

“We would not be here today without the community-minded donors who founded these scholarships. Their generosity ensures that we can assist healthcare professionals who are starting or continuing their careers, and that we can attract and retain the top healthcare minds.”

Scholarships were awarded to Marc Jonelle Pacamalan, Hamrin Kaur, Danielle Odenbach, Dallas Jones, Jodi Collier, Nicole Junck, Kaylin Herzog, Deanna Friesen, Devin Woodland, Victoria Johns, Laura Shapka, Wikrom Praekiat, Cole Brown, Haley Mack, Payton Pluister, Sage Bugutsky, Jessica Nelson, Estel Quinteros, Chloe Roberton, Jennifer Huseby, Charmane Columnas, Lisa Gregoire, Taylor Short, Jennifer Froese, and James Choi.

Health

Horrific and Deadly Effects of Antidepressants

The Vigilant Fox

The Vigilant Fox

Once you see what else these drugs are doing, you’ll never look at depression “treatment” the same way again.

The following information is based on a report originally published by A Midwestern Doctor. Key details have been streamlined and editorialized for clarity and impact. Read the original report here.

Did you know that SSRI antidepressants INCREASE suicidal thoughts by 255%?

A clinical trial on healthy volunteers found that 2 out of 20 became suicidal after taking Zoloft.

One was literally on her way to kill herself when a timely phone call saved her life.

But it’s not just suicidal thoughts that make antidepressants dangerous.

And once you see what else these drugs are doing, you’ll never look at depression “treatment” the same way again.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors—or SSRIs—are one of the most harmful medicines prescribed today.

And that’s saying a lot because the market is FULL of harmful medicines.

What’s so bad about these antidepressants?

First of all, their use is widespread and frequently unjustifiable.

They promise to be a magical solution to depression and anxiety, but it’s quite the opposite.

In fact, they can cause side effects far worse than what they claim to treat.

SSRIs don’t just dull your emotions, and they don’t alter your brain chemistry for the better.

They literally reprogram your brain.

Between 40% and 60% of users report emotional numbness. Not just negative emotions—all emotions.

Joy, pain, motivation—all of it completely flatlined.

Some describe it as “life without color” or a “zombie-like” existence.

Sure, maybe you don’t feel depressed anymore. But you don’t feel anything at all.

That sounds… terrible.

Depression can be serious, but should we accept emotionless zombies as the alternative?

If you want to dig even deeper into the dark side of antidepressants and why they’re so harmful, check out @Midwesterndoc’s comprehensive report on the subject. And be sure to share this with anyone you know who may be considering starting an SSRI.

And it’s not just becoming an emotionless zombie you have to worry about. The emotional shutdown can lead to something that is much worse than depression and anxiety.

I don’t mean just a little anger here and there.

SSRIs are causing people to commit suicide—and yes, even horrific mass shootings.

And guess what? The FDA knew about it.

Prozac triggers hallucinations, mania, and violence, and the FDA has known all along.

Even animals become aggressive on SSRIs.

But instead of going back to the drawing board, the FDA approved it anyway.

After nine years on the market, 39,000 people reported major psychiatric events. And those are only the people who reported it…

Really makes you question FDA approval, doesn’t it?

Did you know most of the mass shooters we hear about in the news were often on SSRIs?

It’s true.

And the media even reported on it. But then, they stopped.

That’s weird.

So why are we “not allowed” to talk about SSRIs and violence anymore?

It’s pretty simple.

It would blow the lid off one of the most dangerous pharmaceutical cover-ups in modern history.

It would expose the truth that Big Pharma knowingly released drugs that could make people snap and kill other people.

And they just kept selling them anyway.

But the psychotic violence caused by SSRIs is only the tip of the iceberg.

Obviously, not everyone taking these drugs becomes a mass shooter. But that doesn’t mean the other side effects are any less terrible for those who experience them.

SSRIs truly warp your mind, body, and emotions. And sometimes it is irreversible.

The numbers are truly chilling:

→ A 255% increase in suicidal thoughts

→ 30% of SSRI users develop Bipolar disorder

→ 59% suffer long-term sexual dysfunction

With many saying their libido never came back even after stopping the drug.

The science is clear. The harm caused by SSRIs greatly outweighs any benefits they provide.

Talk about depressing…

A 2020 study involving 20 healthy volunteers with zero history of depression or other mental illnesses had shocking results.

They were each given Zoloft.

TWO of them BECAME suicidal.

One of them was even on her way to kill herself when a divinely timed phone call interrupted her plans.

These two study participants were still affected several months later. They were actually questioning the stability of their personalities.

This doesn’t sound like a magic solution. This sounds like torture.

Speaking of stopping SSRIs—good luck!

They are highly addictive.

And it’s not just physical addiction. It’s neurological.

And because of what they do to the brain, it can take years to step down the dose and wean off of them. Years!

Withdrawal symptoms include things like:

– Brain zaps

– Panic attacks

– Suicidal spirals

– Derealization

And these symptoms can last weeks, months, or even years.

It’s not uncommon to fail and continue taking them because the withdrawal is just that bad.

A 2022 review found that 56% of users who tried to stop SSRIs experience withdrawal symptoms, and 46% describe it as severe.

Psychiatrists mislabel it as a “relapse” and prescribe even more drugs.

The system is set up to trap you. There’s no exit.

And the most vulnerable groups?

Pregnant women and children.

Despite strong evidence linking SSRIs to birth defects, premature birth, and newborn death, the FDA still endorses their use during pregnancy.

One study showed a six times higher risk of pulmonary hypertension in newborns.

Another study showed that SSRI babies lost height and weight in just 19 weeks.

This isn’t good.

SSRIs are being pushed on everyone. Especially vulnerable people like foster kids, parolees, prisoners, and elderly nursing home residents.

And in many of these cases, there is no real ability for them to say no.

That’s not mental health care. That’s drugging people.

The industry tells us SSRIs are “fixing a serotonin imbalance.”

But that’s a lie.

There’s no solid evidence that depression is caused by low serotonin.

So what’s the real mechanism at play here?

SSRIs alter brain wiring. And obviously not always in good ways.

SSRI users describe feeling like their “personality changed” after starting the drug.

The reports are endless and absolutely chilling.

Some were left numb for years. Others became aggressive, impulsive, or dissociated from reality.

Many say they don’t recognize who they became after taking SSRIs.

Excuse me… what?!

And of course, patients and their families are rarely warned about these effects.

Most say they were never told about the risks. There was no informed consent.

How can you not inform depressed people that their medication might make them suicidal? How is it even possible that we can be asking that question?

They experienced these things and talked to their doctors.

They were gaslit every step of the way.

If you or someone you love is taking SSRIs or is considering taking them, I urge you to read the full report from A Midwestern Doctor

How many more people have to suffer before this ends?

How many more people who reach out to their doctor because something is off and they’re looking for help are going to be hurt, sometimes permanently?

It’s time to expose the cover-up and end Big Pharma’s abuse and gaslighting once and for all.

RFK Jr. is right—this could finally be the turning point.

For 40 years, this tragedy was hidden behind slick ads and corrupted science.

But now it’s in the light and MAHA is ready to fight.

If you know anyone considering starting an SSRI, be sure to forward them this information. Because if you wait until after, it might be too late.

Thanks for reading!

This information was based on a report originally published by A Midwestern Doctor. Key details were streamlined and editorialized for clarity and impact.

Addictions

Addiction experts demand witnessed dosing guidelines after pharmacy scam exposed

By Alexandra Keeler

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

An addiction medicine advocacy group is urging B.C. to promptly issue new guidelines for witnessed dosing of drugs dispensed under the province’s controversial safer supply program.

In a March 24 letter to B.C.’s health minister, Addiction Medicine Canada criticized the BC Centre on Substance Use for dragging its feet on delivering the guidelines and downplaying the harms of prescription opioids.

The centre, a government-funded research hub, was tasked by the B.C. government with developing the guidelines after B.C. pledged in February to return to witnessed dosing. The government’s promise followed revelations that many B.C. pharmacies were exploiting rules permitting patients to take safer supply opioids home with them, leading to abuse of the program.

“I think this is just a delay,” said Dr. Jenny Melamed, a Surrey-based family physician and addiction specialist who signed the Addiction Medicine Canada letter. But she urged the centre to act promptly to release new guidelines.

“We’re doing harm and we cannot just leave people where they are.”

Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter also includes recommendations for moving clients off addictive opioids altogether.

“We should go back to evidence-based medicine, where we have medications that work for people in addiction,” said Melamed.

‘Best for patients’

On Feb. 19, the B.C. government said it would return to a witnessed dosing model. This model — which had been in place prior to the pandemic — will require safer supply participants to take prescribed opioids under the supervision of health-care professionals.

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

In its Feb. 19 announcement, the province said new participants in the safer supply program would immediately be subject to the witnessed dosing requirement. For existing clients of the program, new guidelines would be forthcoming.

“The Ministry will work with the BC Centre on Substance Use to rapidly develop clinical guidelines to support prescribers that also takes into account what’s best for patients and their safety,” Kendra Wong, a spokesperson for B.C.’s health ministry, told Canadian Affairs in an emailed statement on Feb. 27.

More than a month later, addiction specialists are still waiting.

According to Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter, the BC Centre on Substance Use posed “fundamental questions” to the B.C. government, potentially causing the delay.

“We’re stuck in a place where the government publicly has said it’s told BCCSU to make guidance, and BCCSU has said it’s waiting for government to tell them what to do,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

This lag has frustrated addiction specialists, who argue the lack of clear guidance is impeding the transition to witnessed dosing and jeopardizing patient care. They warn that permitting take-home drugs leads to more diversion onto the streets, putting individuals at greater risk.

“Diversion of prescribed alternatives expands the number of people using opioids, and dying from hydromorphone and fentanyl use,” reads the letter, which was also co-signed by Dr. Robert Cooper and Dr. Michael Lester. The doctors are founding board members of Addiction Medicine Canada, a nonprofit that advises on addiction medicine and advocates for research-based treatment options.

“We have had people come in [to our clinic] and say they’ve accessed hydromorphone on the street and now they would like us to continue [prescribing] it,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

A spokesperson for the BC Centre on Substance Use declined to comment, referring Canadian Affairs to the Ministry of Health. The ministry was unable to provide comment by the publication deadline.

Big challenges

Under the witnessed dosing model, doctors, nurses and pharmacists will oversee consumption of opioids such as hydromorphone, methadone and morphine in clinics or pharmacies.

The shift back to witnessed dosing will place significant demands on pharmacists and patients. In April 2024, an estimated 4,400 people participated in B.C.’s safer supply program.

Chris Chiew, vice president of pharmacy and health-care innovation at the pharmacy chain London Drugs, told Canadian Affairs that the chain’s pharmacists will supervise consumption in semi-private booths.

Nathan Wong, a B.C.-based pharmacist who left the profession in 2024, fears witnessed dosing will overwhelm already overburdened pharmacists, creating new barriers to care.

“One of the biggest challenges of the retail pharmacy model is that there is a tension between making commercial profit, and being able to spend the necessary time with the patient to do a good and thorough job,” he said.

“Pharmacists often feel rushed to check prescriptions, and may not have the time to perform detailed patient counselling.”

Others say the return to witnessed dosing could create serious challenges for individuals who do not live close to health-care providers.

Shelley Singer, a resident of Cowichan Bay, B.C., on Vancouver Island, says it was difficult to make multiple, daily visits to a pharmacy each day when her daughter was placed on witnessed dosing years ago.

“It was ridiculous,” said Singer, whose local pharmacy is a 15-minute drive from her home. As a retiree, she was able to drive her daughter to the pharmacy twice a day for her doses. But she worries about patients who do not have that kind of support.

“I don’t believe witnessed supply is the way to go,” said Singer, who credits safer supply with saving her daughter’s life.

Melamed notes that not all safer supply medications require witnessed dosing.

“Methadone is under witness dosing because you start low and go slow, and then it’s based on a contingency management program,” she said. “When the urine shows evidence of no other drug, when the person is stable, [they can] take it at home.”

She also noted that Suboxone, a daily medication that prevents opioid highs, reduces cravings and alleviates withdrawal, does not require strict supervision.

Kendra Wong, of the B.C. health ministry, told Canadian Affairs that long-acting medications such as methadone and buprenorphine could be reintroduced to help reduce the strain on health-care professionals and patients.

“There are medications available through the [safer supply] program that have to be taken less often than others — some as far apart as every two to three days,” said Wong.

“Clinicians may choose to transition patients to those medications so that they have to come in less regularly.”

Such an approach would align with Addiction Medicine Canada’s recommendations to the ministry.

The group says it supports supervised dosing of hydromorphone as a short-term solution to prevent diversion. But Melamed said the long-term goal of any addiction treatment program should be to reduce users’ reliance on opioids.

The group recommends combining safer supply hydromorphone with opioid agonist therapies. These therapies use controlled medications to reduce withdrawal symptoms, cravings and some of the risks associated with addiction.

They also recommend limiting unsupervised hydromorphone to a maximum of five 8 mg tablets a day — down from the 30 tablets currently permitted with take-home supplies. And they recommend that doses be tapered over time.

“This protocol is being used with success by clinicians in B.C. and elsewhere,” the letter says.

“Please ensure that the administrative delay of the implementation of your new policy is not used to continue to harm the public.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

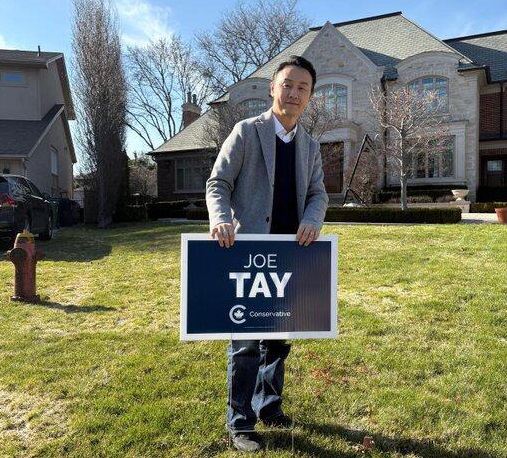

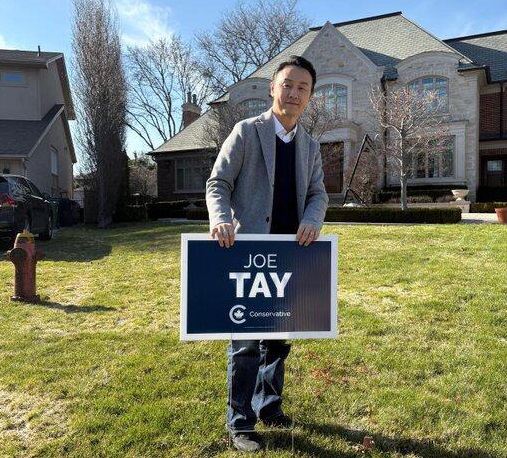

2025 Federal Election1 day agoOttawa Confirms China interfering with 2025 federal election: Beijing Seeks to Block Joe Tay’s Election

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoIndigenous-led Projects Hold Key To Canada’s Energy Future

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoMany Canadians—and many Albertans—live in energy poverty

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoHow Canada’s Mainstream Media Lost the Public Trust

-

2025 Federal Election16 hours ago

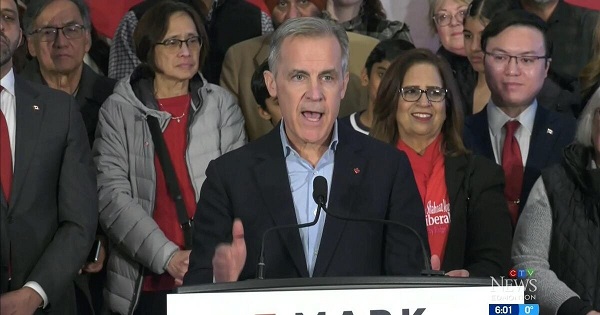

2025 Federal Election16 hours agoBREAKING: THE FEDERAL BRIEF THAT SHOULD SINK CARNEY

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada Urgently Needs A Watchdog For Government Waste

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

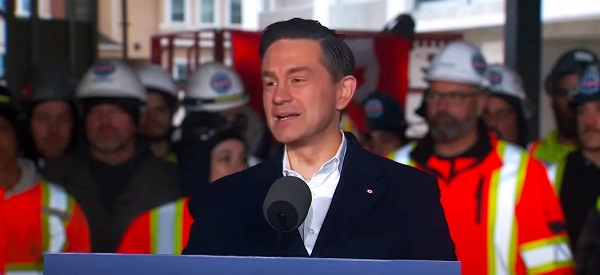

2025 Federal Election1 day agoReal Homes vs. Modular Shoeboxes: The Housing Battle Between Poilievre and Carney

-

2025 Federal Election17 hours ago

2025 Federal Election17 hours agoCHINESE ELECTION THREAT WARNING: Conservative Candidate Joe Tay Paused Public Campaign