First Nations

Red Deer Catholic Regional Schools contest to build awareness for Orange Shirt Day

For Orange Shirt Day this year, Red Deer Catholic Regional Schools First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Support Team hosted a button design contest that was open to all students. In this contest, students were required to come up with a design for Orange Shirt Day that honoured the legacy of residential schools.

“I was thrilled to hear that she had won! Ava is such a talented artist and she took the contest very seriously. She got to work right away and spent every minute on it. When she handed it to me, she a beaming smile on her face. Then I received the email she had won my heart jumped because this is going to someone with an extraordinary talent for drawing. I am ecstatic for her,” said Haley Khatib, teacher at St. Elizabeth Seton School.

Ava LaGrange, a Grade 5 student from St. Elizabeth Seton School artwork is the winning button. On Orange Shirt Day, her artwork will be distributed to her school in the form of buttons. In addition, St. Francis of Assisi Middle School students and staff created the buttons.

First Nations

Ottawa’s Land Claims Program Is Spiralling Out Of Control

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Ottawa paid $7.1B for land claims in 2024-25 alone, raising concern that soaring costs and weak accountability are shortchanging taxpayers

Ottawa is quietly handing out billions in Indigenous land claims, and the costs are soaring far beyond what most Canadians realize.

A new report from Tom Flanagan, professor emeritus at the University of Calgary and senior fellow at the Fraser Institute, warns the federal government’s specific claims program is spiralling out of control. In the 2024-25 fiscal year alone, Ottawa settled 69 claims worth $7.1 billion. Just a decade earlier, in 2014-15, only 15 claims were settled, at a total cost of $36 million. That’s an increase of nearly 200 times in dollar value.

At the centre of the problem is a 2017 directive from then-justice minister Jody Wilson-Raybould. It told federal lawyers to negotiate settlements instead of contesting Indigenous claims in court. Framed as a conciliatory approach, the directive has instead prevented government lawyers from defending decisions made more than a century ago.

The result is that Ottawa is conceding even weak cases, creating a flood of settlements with little accountability to taxpayers footing the bill.

Many of these cases, often called “cows and plows” claims, involve allegations that Ottawa underpaid bands for livestock, equipment or other provisions promised in historical treaties. At the time, the sums were often just a few hundred dollars. But with decades of compound interest added, those claims have ballooned into multimillion-dollar payouts. Flanagan argues that compensation must be grounded in fairness, not in payouts so large they threaten the public purse.

To restore fairness and accountability, Flanagan’s report lays out a clear path forward:

- Rescind the practice directive that ties the hands of government lawyers in resolving claims from Indigenous bands;

- Recognize that bands have already had more than 50 years to make claims, so it is time to set a date when new claims will not be accepted;

- Ensure that the First Nations Fiscal Transparency Act is enforced; and

- Reject the Assembly of First Nations’ proposal that would substantially increase the number and values of claims.

Flanagan warns that without these changes, the program will continue to expand, putting Canadian taxpayers at greater risk and undermining confidence in the system.

Transparency is central to any fair system, yet here, too, Ottawa has failed. In 2016, the federal government announced that bands would face no penalties for failing to file financial reports. Predictably, compliance has dropped.

By 2024, only 260 of Canada’s roughly 630 bands—just 41 per cent—had submitted reports. If Indigenous governments want recognition as autonomous authorities, they must also meet the same standards of transparency required of provinces, municipalities and school boards. Canadians deserve no less.

Those failures come with a steep price. As of March 31, 2023, the federal government reported $76 billion in outstanding obligations, including costs for pensions, environmental cleanup and legal settlements. More than half—$42.7 billion—was tied to Indigenous land claims. These obligations don’t just sit on the books; they threaten Canada’s broader economic health. Unless Ottawa regains control, the costs will continue to climb, undermining fiscal stability.

The consequences of inaction will be severe. If the country slips into recession under the weight of ballooning obligations, Indigenous communities—many already struggling economically—will be among the hardest hit.

A program meant to deliver justice could end up worsening conditions for the very people it was designed to help.

Canadians want fairness for First Nations. But they also deserve accountability for how billions in tax dollars are spent. Flanagan’s report, Specific Claims: An Out-of-Control Program, gives Ottawa a roadmap to deliver both. The question now is whether the federal government has the courage to act before the costs spiral even further out of control.

Rodney A. Clifton is a professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba and a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. Along with Mark DeWolf, he is the editor of From Truth Comes Reconciliation: An Assessment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report (2024).

Business

A Practical Path to Improved Indigenous Relations

By Tom Flanagan

“Reconciliation” has been the watchword for Canada’s relationship with its Indigenous peoples for the last 10 years. So, how’s that going? Not so well, in my opinion. Canada has apologized profusely for Indian Residential Schools, including imaginary unmarked graves and missing children. As prime minister, Justin Trudeau tripled the Indigenous budgetary envelope, his government committing to pay tens of billions of dollars in reparations for alleged deficiencies not just of residential schools but day schools, Indian hospitals, adoption and child welfare services and other policy failings.

Yet when Prime Minister Mark Carney recently brought in legislation to facilitate construction of desperately needed major projects, prominent First Nations leaders focused on the perceived affront to their powers and privileges, with some threatening to block Carney’s entire initiative by reviving the Idle No More protests and blockades of the 2010s.

Our current impasse arises from 250 years of decisions that are now almost impossible to change because they have been made part of Canada’s Constitution, either by elected politicians or by appointed judges. “Big new ideas” are thus virtually impossible to implement. But there is still room for incremental innovations in public policy that focus primarily on economic opportunities benefiting Indigenous Canadians, i.e., on pursuing prosperity and the good things that come with that.

In my opinion, Canada’s First Nations have two major ways to achieve prosperity. Those bands located near cities and large towns can pursue commercial and residential real estate development, as a number are doing – witness, for example, the large Taza development led by the Tsuut’ina (Sarcee) nation along Calgary’s southwest section of its Ring Road.

Those in more remote locations, meanwhile, can pursue natural resource-based development such as oil and natural gas, hard rock mining, hydroelectricity, fisheries and tourism. Unfortunately, much resource development has been blocked by environmental purists in coalition with the minority of First Nations people opposed in principle to modernization.

Emblematic of this dynamic was the bitter opposition by a small number of First Nations members to the Coastal GasLink natural gas pipeline in northern B.C. that was to feed the new LNG Canada liquefied natural gas terminal at the West Coast port of Kitimat – a project heavily favoured by the Haisla Nation, which has basically staked its economic future on LNG. Despite the opponents’ vandalism and violence, fortunately the pipeline was built and Canada’s first cargo of LNG recently departed Kitimat for markets in East Asia.

So this is clearly an avenue of progress. Indigenous equity ownership of resource projects does not require constitutional changes, and it will help to solidify First Nations’ support for such projects as well as increase the standard of living of participants. With judicious investment, there can more First Nation success stories to rival real estate development at Westbank, B.C. and oil sands service industries at Fort McKay.

Loans and loan guarantees are not without risk, however, and sometimes the risks are great. When offering equity ownership to First Nations, it would be best to concentrate on smaller and medium-sized projects where due diligence is possible and political interference can be minimized.

It also would make sense to diminish First Nations’ current obsession with grievances and reparations. Much of this is derived from Jodi Wilson-Raybould’s “practice directive” issued when she was Trudeau’s Minister of Justice, instructing federal lawyers to prefer negotiation over litigation, i.e., no longer to vigorously defend the Government of Canada’s legal position in court, but essentially to surrender. This document has no constitutional status and can be repealed by a government that realizes how much damage it is doing.

Then there is the reserve system, the bête noire of so many critics. Even as there is no constitutional prospect of abolishing Canada’s system of some 600 mostly small and often economically unviable reserves, there is no good reason for making them artificially attractive places to live, either – as has been done by making them havens from income and sales taxes. This came about through a wrong-headed 1983 Supreme Court decision, Nowegijick v. The Queen, expanding the immunity from property tax conferred by the Indian Act to cover income taxes as well.

But this exemption is based on legislation, not the Constitution; thus, Parliament could change it through ordinary legislation. Ending or reducing the tax haven status could be part of a larger deal to help First Nations participate more fully in the economy through a program of loans and loan guarantees.

These changes are modest, but now is the right time to consider them. It is widely agreed that, even apart from Trumpian threats, Canada needs policy renovation after a decade of Justinian progressivism. The federal debt has doubled, the annual deficit is spiralling out of control, our defence effort is underfunded, and declining labour productivity has affected our ability to pay for basic public services.

Endless moralizing plus grotesque overspending in the name of reconciliation symbolizes the progressive concern with what Friedrich Hayek called “the mirage of social justice” to the detriment of other affairs of state. It’s high time for a course correction in many areas, including Indigenous policy.

The original, full-length version of this article was recently published in C2C Journal.

Tom Flanagan is professor emeritus of political science at the University of Calgary.

-

Crime9 hours ago

Crime9 hours agoPublic Execution of Anti-Cartel Mayor in Michoacán Prompts U.S. Offer to Intervene Against Cartels

-

Alberta8 hours ago

Alberta8 hours agoCanada’s heavy oil finds new fans as global demand rises

-

Bruce Dowbiggin6 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin6 hours agoA Story So Good Not Even The Elbows Up Crew Could Ruin It

-

Environment10 hours ago

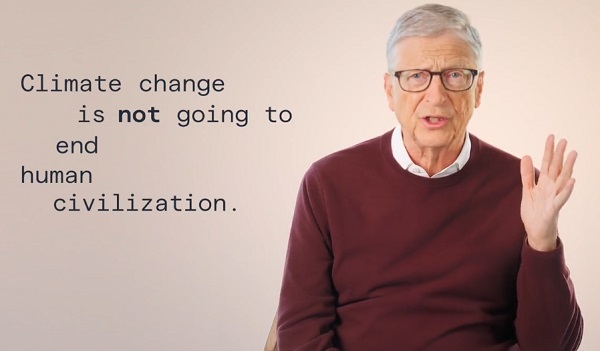

Environment10 hours agoThe era of Climate Change Alarmism is over

-

Addictions7 hours ago

Addictions7 hours agoThe War on Commonsense Nicotine Regulation

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney budget doubles down on Trudeau-era policies

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoCrown still working to put Lich and Barber in jail

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney budget continues misguided ‘Build Canada Homes’ approach