Brownstone Institute

Reconsidering Lockdowns

BY

Recent news and research on lockdowns has reminded me of my personal conversations and a few small articles that I wrote last year. In my interactions with a few scientists and policymakers, at first we debated in an attempt to be objective and rational, but after a time we grew tired of arguing and gave up on debating the science of covid interventions.

Our factions crystallized and hardened, and an uneasy tension persists. It takes a lot of energy, courage, humility, and patience, to reconsider one’s position. But for reasons that I will outline below, I think it is crucial that we do so.

At the beginning of covid lockdowns, I read many scientific articles in an attempt to understand what was happening. I found little evidence to suggest that the official recommendations were entirely reasonable. I felt sure that a stay-inside mandate was wrong-headed, because I knew that sun exposure and Vitamin D are helpful for immune health. So, while I avoided contact with other people, I went for long daily walks (while avoiding the police and their much-publicized fines). However well-intentioned the government’s rules may have been, their mostly negative effect has been shown in a stream of scientific articles that flowed more and more copiously as the data came in.

I didn’t speak about this publicly until the late summer of 2021, when Italy imposed the “Green Pass,” a vaccine passport which was rushed through lawmaking bodies in August and implemented in successively stringent versions on all of Italian society in the early fall. At that point, I felt it was my duty to speak.

At the beginning of September, I published a short post on Facebook with a graphic showing that, among Italy, Germany, and Sweden, the lowest case fatality rate for Covid-19 was in Sweden, and I reminded my friends that it was the latter that did not require any lockdown and did not require the use of face-masks nor “Ausweisdokumente.”

I was so deeply angered by the Green Pass that I publicly compared it to the papers required by Germany’s Third Reich. The comparison understandably raises hackles, but building a society on a “papers please” basis is typical of totalitarianism, not democracy. We have not yet arrived at forced euthanasia or sterilization — we hope — but we have arrived at the breakdown of bodily integrity, the exclusion of certain categories of citizens from the workplace, and physical internment for the non-compliant in several Western countries.

My dramatic comparison serves to emphasize that we have taken measures that lead to total control over human lives, and that total control opens the door to horrific outcomes. We must repudiate totalitarianism, whether explicit or subtly creeping.

Research is emerging now — science takes time — that suggests that the Green Pass and other similar coercive measures across the world did not positively affect the outcomes of public health. Studies to this effect are collected here and here. The divisions that arose in our societies due to these measures are deep, and have hardly begun to heal. They are only papered over with a veneer of civil discourse, but in my experience, the positions we held a year ago, we still hold with even greater intensity, albeit in silence.

We don’t talk about it. Like prehistoric tribes, we don’t affirm our common humanity. Instead, we divide the world into the holy and the unholy, the obedient and the rebellious, the vaxxed and the unvaxxed. And “silence like a cancer grows,” as Simon and Garfunkel sang.

The day after my Facebook post, a friend who works at the IMF, who was studying the impact of covid and various interventions that had been implemented in South America sent me an article by Kowall et al., which purported to show that, contrary to the direct comparison of mortality between Germany and Sweden, Sweden’s results were much worse if demographic development was taken into account, by modeling increasing life expectancy.

I read the study and wrote a brief rebuttal on Medium because Kowall et al. only considered the year 2020. I also emailed Kowall and asked him to send me the details of how he had carried out his analysis in order to extend it to include data from 2021. Judging by the excess mortality charts, I felt sure that his conclusions would have to be reconsidered if they took into account a longer time series. He did not respond.

My friend at the IMF and I continued to debate the issue for a few more days. I sent him this article and this one; he sent me this and that, and then we settled on a somewhat tense silence before sharing a few soccer and rock music videos with each other. There was an elephant in the room. We both avoided it, like the magical family in Encanto (“We don’t talk about Bruno…!”). But the elephant remained.

In January 2022, the Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics published a working paper which showed clearly how lockdowns across the world did not affect COVID-19 mortality at all. I felt vindicated that the earlier studies I shared with my friend at the IMF and my Facebook followers had been correct, validated by one of the leading mainstream voices on public health. But I was weary of arguing and did not post the article. Saying “I told you so” felt like bad form.

So why bring it up now, nine months later? It is worth talking about it again, even if we are all tired of it, because the reason we played along with lockdowns was that we trusted the government authorities who imposed them. We believed in making a sacrifice for the greater good. We believed that our leaders had access to good information and would never silence their unfortunately-correct critics willfully and stupidly. We believed that if they brutally quelled dissent both online with an unprecedented censorship campaign and offline with rubber bullets and tear gas, they did so for our benefit.

Lockdowns shredded the social contract. They splintered society into violently opposed factions. (They damaged religions, they contributed to the inflation disaster, they contributed to roughly doubling the food price index, they led to mass surveillance, etc). And if the governments got lockdowns so wrong, why should we believe that they got other things right? This is still a relevant question as we careen toward energy rationing and food crises and already see inflation at around 10%.

The Johns Hopkins study was finalized and published on May 20th, 2022, and continues to affirm that “lockdowns in the spring of 2020 had little to no effect on COVID-19 mortality.” Another study from the National Bureau of Economic Research estimates that 170,000 young Americans died in 2020 and 2021, not from COVID but from lockdown. These estimates come from the same mainstream sources who championed lockdowns a year before.

Some try to justify themselves by saying that “the science has changed,” but the excuse is lame when reputable scientists were making that point at the crucial moment when decisions were being made. Some of the most prestigious and courageous who did so, the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration, were banned from social media for stating the then-heretical but obvious truth that public health interventions must be made with a cost-benefit analysis.

The studies are piling up. Sweden’s approach to lockdowns has been shown over and over again to be the best approach by many measures. The World Health Organization recently concurred in a study of excess mortality through 2020 and 2021. And yet, incredibly, the same World Health Organization seeks to make lockdowns standard practice, inverting their previous guidelines, which reasonably admitted that respiratory viruses spread too quickly to be stopped in this way.

Now, the WHO says that curbing viral transmission is the aim of pandemic response. Two years of experience across the world show that this is not possible and causes grave harms that are worse than the virus itself.

So Kowall et al., my friend at the IMF, one hundred other public figures here, and all you gentle readers who are tired of talking about lockdowns, please find enough patience, humility, and love for the facts and for the lives of your fellow citizens to reconsider and publicly retract the positions which erroneously support lockdowns as a reasonable intervention. We cannot afford these mistakes from our politicians, and we must not support them when their measures work against the public good.

Brownstone Institute

If the President in the White House can’t make changes, who’s in charge?

From the Brownstone Institute

By

Who Controls the Administrative State?

President Trump on March 20, 2025, ordered the following: “The Secretary of Education shall, to the maximum extent appropriate and permitted by law, take all necessary steps to facilitate the closure of the Department of Education.”

That is interesting language: to “take all necessary steps to facilitate the closure” is not the same as closing it. And what is “permitted by law” is precisely what is in dispute.

It is meant to feel like abolition, and the media reported it as such, but it is not even close. This is not Trump’s fault. The supposed authoritarian has his hands tied in many directions, even over agencies he supposedly controls, the actions of which he must ultimately bear responsibility.

The Department of Education is an executive agency, created by Congress in 1979. Trump wants it gone forever. So do his voters. Can he do that? No but can he destaff the place and scatter its functions? No one knows for sure. Who decides? Presumably the highest court, eventually.

How this is decided – whether the president is actually in charge or really just a symbolic figure like the King of Sweden – affects not just this one destructive agency but hundreds more. Indeed, the fate of the whole of freedom and functioning of constitutional republics may depend on the answer.

All burning questions of politics today turn on who or what is in charge of the administrative state. No one knows the answer and this is for a reason. The main functioning of the modern state falls to a beast that does not exist in the Constitution.

The public mind has never had great love for bureaucracies. Consistent with Max Weber’s worry, they have put society in an impenetrable “iron cage” built of bloodless rationalism, needling edicts, corporatist corruption, and never-ending empire-building checked by neither budgetary restraint nor plebiscite.

Today’s full consciousness of the authority and ubiquity of the administrative state is rather new. The term itself is a mouthful and doesn’t come close to describing the breadth and depth of the problem, including its root systems and retail branches. The new awareness is that neither the people nor their elected representatives are really in charge of the regime under which we live, which betrays the whole political promise of the Enlightenment.

This dawning awareness is probably 100 years late. The machinery of what is popularly known as the “deep state” – I’ve argued there are deep, middle, and shallow layers – has been growing in the US since the inception of the civil service in 1883 and thoroughly entrenched over two world wars and countless crises at home and abroad.

The edifice of compulsion and control is indescribably huge. No one can agree precisely on how many agencies there are or how many people work for them, much less how many institutions and individuals work on contract for them, either directly or indirectly. And that is just the public face; the subterranean branch is far more elusive.

The revolt against them all came with the Covid controls, when everyone was surrounded on all sides by forces outside our purview and about which the politicians knew not much at all. Then those same institutional forces appear to be involved in overturning the rule of a very popular politician whom they tried to stop from gaining a second term.

The combination of this series of outrages – what Jefferson in his Declaration called “a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object” – has led to a torrent of awareness. This has translated into political action.

A distinguishing mark of Trump’s second term has been an optically concerted effort, at least initially, to take control of and then curb administrative state power, more so than any executive in living memory. At every step in these efforts, there has been some barrier, even many on all sides.

There are at least 100 legal challenges making their way through courts. District judges are striking down Trump’s ability to fire workers, redirect funding, curb responsibilities, and otherwise change the way they do business.

Even the signature early achievement of DOGE – the shuttering of USAID – has been stopped by a judge with an attempt to reverse it. A judge has even dared tell the Trump administration who it can and cannot hire at USAID.

Not a day goes by when the New York Times does not manufacture some maudlin defense of the put-upon minions of the tax-funded managerial class. In this worldview, the agencies are always right, whereas any elected or appointed person seeking to rein them in or terminate them is attacking the public interest.

After all, as it turns out, legacy media and the administrative state have worked together for at least a century to cobble together what was conventionally called “the news.” Where would the NYT or the whole legacy media otherwise be?

So ferocious has been the pushback against even the paltry successes and often cosmetic reforms of MAGA/MAHA/DOGE that vigilantes have engaged in terrorism against Teslas and their owners. Not even returning astronauts from being “lost in space” has redeemed Elon Musk from the wrath of the ruling class. Hating him and his companies is the “new thing” for NPCs, on a long list that began with masks, shots, supporting Ukraine, and surgical rights for gender dysphoria.

What is really at stake, more so than any issue in American life (and this applies to states around the world) – far more than any ideological battles over left and right, red and blue, or race and class – is the status, power, and security of the administrative state itself and all its works.

We claim to support democracy yet all the while, empires of command-and-control have arisen among us. The victims have only one mechanism available to fight back: the vote. Can that work? We do not yet know. This question will likely be decided by the highest court.

All of which is awkward. It is impossible to get around this US government organizational chart. All but a handful of agencies live under the category of the executive branch. Article 2, Section 1, says: “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.”

Does the president control the whole of the executive branch in a meaningful way? One would think so. It’s impossible to understand how it could be otherwise. The chief executive is…the chief executive. He is held responsible for what these agencies do – we certainly blasted away at the Trump administration in the first term for everything that happened under his watch. In that case, and if the buck really does stop at the Oval Office desk, the president must have some modicum of control beyond the ability to tag a marionette to get the best parking spot at the agency.

What is the alternative to presidential oversight and management of the agencies listed in this branch of government? They run themselves? That claim means nothing in practice.

For an agency to be deemed “independent” turns out to mean codependency with the industries regulated, subsidized, penalized, or otherwise impacted by its operations. HUD does housing development, FDA does pharmaceuticals, DOA does farming, DOL does unions, DOE does oil and turbines, DOD does tanks and bombs, FAA does airlines, and so on It goes forever.

That’s what “independence” means in practice: total acquiescence to industrial cartels, trade groups, and behind-the-scenes systems of payola, blackmail, and graft, while the powerless among the people live with the results. This much we have learned and cannot unlearn.

That is precisely the problem that cries out for a solution. The solution of elections seems reasonable only if the people we elected actually have the authority over the thing they seek to reform.

There are criticisms of the idea of executive control of executive agencies, which is really nothing other than the system the Founders established.

First, conceding more power to the president raises fears that he will behave like a dictator, a fear that is legitimate. Partisan supporters of Trump won’t be happy when the precedent is cited to reverse Trump’s political priorities and the agencies turn on red-state voters in revenge.

That problem is solved by dismantling agency power itself, which, interestingly, is mostly what Trump’s executive orders have sought to achieve and which the courts and media have worked to stop.

Second, one worries about the return of the “spoils system,” the supposedly corrupt system by which the president hands out favors to friends in the form of emoluments, a practice the establishment of the civil service was supposed to stop.

In reality, the new system of the early 20th century fixed nothing but only added another layer, a permanent ruling class to participate more fully in a new type of spoils system that operated now under the cloak of science and efficiency.

Honestly, can we really compare the petty thievery of Tammany Hall to the global depredations of USAID?

Third, it is said that presidential control of agencies threatens to erode checks and balances. The obvious response is the organizational chart above. That happened long ago as Congress created and funded agency after agency from the Wilson to the Biden administration, all under executive control.

Congress perhaps wanted the administrative state to be an unannounced and unaccountable fourth branch, but nothing in the founding documents created or imagined such a thing.

If you are worried about being dominated and destroyed by a ravenous beast, the best approach is not to adopt one, feed it to adulthood, train it to attack and eat people, and then unleash it.

The Covid years taught us to fear the power of the agencies and those who control them not just nationally but globally. The question now is two-fold: what can be done about it and how to get from here to there?

Trump’s executive order on the Department of Education illustrates the point precisely. His administration is so uncertain of what it does and can control, even of agencies that are wholly executive agencies, listed clearly under the heading of executive agencies, that it has to dodge and weave practical and legal barriers and land mines, even in its own supposed executive pronouncements, even to urge what might amount to be minor reforms.

Whoever is in charge of such a system, it is clearly not the people.

Brownstone Institute

The New Enthusiasm for Slaughter

From the Brownstone Institute

By

What War Means

My mother once told me how my father still woke up screaming in the night years after I was born, decades after the Second World War (WWII) ended. I had not known – probably like most children of those who fought. For him, it was visions of his friends going down in burning aircraft – other bombers of his squadron off north Australia – and to be helpless, watching, as they burnt and fell. Few born after that war could really appreciate what their fathers, and mothers, went through.

Early in the movie Saving Private Ryan, there is an extended D-Day scene of the front doors of the landing craft opening on the Normandy beaches, and all those inside being torn apart by bullets. It happens to one landing craft after another. Bankers, teachers, students, and farmers being ripped in pieces and their guts spilling out whilst they, still alive, call for help that cannot come. That is what happens when a machine gun opens up through the open door of a landing craft, or an armored personnel carrier, of a group sent to secure a tree line.

It is what a lot of politicians are calling for now.

People with shares in the arms industry become a little richer every time one of those shells is fired and has to be replaced. They gain financially, and often politically, from bodies being ripped open. This is what we call war. It is increasingly popular as a political strategy, though generally for others and the children of others.

Of course, the effects of war go beyond the dismembering and lonely death of many of those fighting. Massacres of civilians and rape of women can become common, as brutality enables humans to be seen as unwanted objects. If all this sounds abstract, apply it to your loved ones and think what that would mean.

I believe there can be just wars, and this is not a discussion about the evil of war, or who is right or wrong in current wars. Just a recognition that war is something worth avoiding, despite its apparent popularity amongst many leaders and our media.

The EU Reverses Its Focus

When the Brexit vote determined that Britain would leave the European Union (EU), I, like many, despaired. We should learn from history, and the EU’s existence had coincided with the longest period of peace between Western European States in well over 2,000 years.

Leaving the EU seemed to be risking this success. Surely, it is better to work together, to talk and cooperate with old enemies, in a constructive way? The media, and the political left, center, and much of the right seemed at that time, all of nine years ago, to agree. Or so the story went.

We now face a new reality as the EU leadership scrambles to justify continuing a war. Not only continuing, but they had been staunchly refusing to even countenance discussion on ending the killing. It has taken a new regime from across the ocean, a subject of European mockery, to do that.

In Europe, and in parts of American politics, something is going on that is very different from the question of whether current wars are just or unjust. It is an apparent belief that advocacy for continued war is virtuous. Talking to leaders of an opposing country in a war that is killing Europeans by the tens of thousands has been seen as traitorous. Those proposing to view the issues from both sides are somehow “far right.”

The EU, once intended as an instrument to end war, now has a European rearmament strategy. The irony seems lost on both its leaders and its media. Arguments such as “peace through strength” are pathetic when accompanied by censorship, propaganda, and a refusal to talk.

As US Vice-President JD Vance recently asked European leaders, what values are they actually defending?

Europe’s Need for Outside Help

A lack of experience of war does not seem sufficient to explain the current enthusiasm to continue them. Architects of WWII in Europe had certainly experienced the carnage of the First World War. Apart from the financial incentives that human slaughter can bring, there are also political ideologies that enable the mass death of others to be turned into an abstract and even positive idea.

Those dying must be seen to be from a different class, of different intelligence, or otherwise justifiable fodder to feed the cause of the Rules-Based Order or whatever other slogan can distinguish an ‘us’ from a ‘them’…While the current incarnation seems more of a class thing than a geographical or nationalistic one, European history is ripe with variations of both.

Europe appears to be back where it used to be, the aristocracy burning the serfs when not visiting each other’s clubs. Shallow thinking has the day, and the media have adapted themselves accordingly. Democracy means ensuring that only the right people get into power.

Dismembered European corpses and terrorized children are just part of maintaining this ideological purity. War is acceptable once more. Let’s hope such leaders and ideologies can be sidelined by those beyond Europe who are willing to give peace a chance.

There is no virtue in the promotion of mass death. Europe, with its leadership, will benefit from outside help and basic education. It would benefit even further from leadership that values the lives of its people.

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoIce Surprises – Arctic and Antarctic Ice Sheets Are Stabilizing and Growing

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoEnergy projects occupy less than three per cent of Alberta’s oil sands region, report says

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCarney’s energy superpower rhetoric falls flat without policy certainty

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoOil tankers in Vancouver are loading plenty, but they can load even more

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCharges laid in record cocaine seizure

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

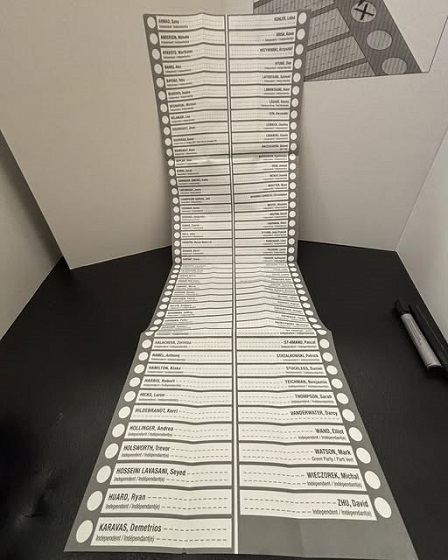

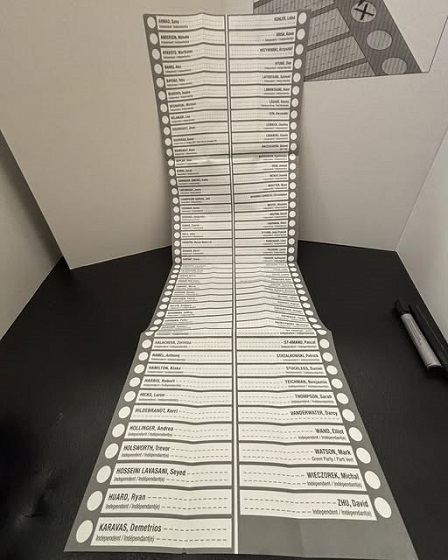

2025 Federal Election1 day agoGroup that added dozens of names to ballot in Poilievre’s riding plans to do it again

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoCarney says Liberals won’t make voting pact with NDP

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoStudy finds nearly half of ‘COVID deaths’ had no link to virus