Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Public opposition in Regina halts Dewdney Avenue renaming as Kamloops mass grave allegations unravel

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Lee Harding

Three years after taking down a statue of Canada’s first Prime Minister, Regina decides not to change street named after a far more controversial historical figure.

In a sign of the times, the same City of Regina that removed a statue of John A. MacDonald has just preserved the name of former Indian Commissioner Edgar Dewdney.

Dewdney, a Conservative MP under MacDonald, became Indian Commissioner of the North-West Territories in 1879 and was named Lieutenant Governor of the territory in 1881. He served in both positions until 1888. He was, briefly, the Minister of Indian Affairs before being appointed Lieutenant- Governor of British Columbia.

It was Dewdney who decided to move the territorial capital from Battleford to Wascana in 1882, later renamed Regina. He also moved the North-West Mounted Police headquarters to Regina from Fort Walsh: the fact that Dewdney had land nearby was likely not coincidental.

In 1883, Dewdney wrote to MacDonald to back the 1879 Davin Report in support of residential industrial schools, saying they “might be carried on with great advantage to the Indians.” The Davin Report, written by Nicholas Flood Davin, a journalist and politician, was commissioned by the Canadian government to provide recommendations on the establishment of residential schools for Indigenous children.

Despite this enormous contribution to Regina and Canadian history, Regina city councillors Andrew Stevens and Dan LeBlanc made a motion last May to remove Dewdney’s name from a street, park, and public pool.

The prospects seemed good. After all, the city of Regina decided to remove the statue of Sir John A. Macdonald from Victoria Park in 2021, primarily due to his role in the creation of Canada’s residential school system.

Dewdney was neither a father of Confederation nor a prime minister but is often viewed as a more controversial figure in Canadian history. He actively supported the residential school system, believing it to be more effective than day schools in breaking the influence of Indigenous families and communities. His policies were designed to assimilate Indigenous children by separating them from their cultural roots.

He refused to allocate certain lands promised to Indigenous communities under treaty agreements. He also withheld food rations, which were crucial during times of famine, using them as leverage to force Indigenous bands to relocate further north, where the government wanted them to settle. These actions contributed to widespread suffering and are part of his contentious legacy.

Yet on August 21, by a vote of seven to three, Regina city council refused to rename the 12-km Dewdney Avenue. Ward 10 councillor Jason Mancinelli said the change would cause too much hassle for businesses and people on the street.

Mayor Sandra Masters, who is seeking re-election, estimated that renaming Dewdney Avenue could cost around $350,000. She argued that this amount could be better spent on other priorities in the city.

“There are other things we could invest in that wouldn’t be as divisive,” she said.

So, what changed between 2021 and now?

In 2021, the city removed Macdonald’s statue following a brief, one-sided consultation shortly after the Kamloops Residential School mass grave allegations. At the time, ground-penetrating radar suggested potential burial sites, prompting widespread reactions across Canada.

Three years later, the investigation into the allegations, at a cost of $8 million, has yet to uncover any bodies. Some experts suggest that soil disturbances detected by the scans might have been caused by shallow trenches dug for a septic field back in 1924 rather than unmarked graves as initially alleged.

In contrast, Regina introduced the issue of renaming Dewdney Avenue in May and held presentations in June of this year, long after the Kamloops allegations started to unravel. The decision on the name change was delayed long enough for those opposed to speak up. Apparently, the suggested replacement name Tatanka – the Cree word for bison – did not seem to resonate with many of those opposed to the renaming.

The takeaway from these two outcomes is clear: rushed decisions can lead to unintended consequences, while a more thoughtful, measured approach ensures that choices are better informed and more beneficial to the community.

Lee Harding is a Research Fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Education

Our Kids Are Struggling To Read. Phonics Is The Easy Fix

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

One Manitoba school division is proving phonics works

If students don’t learn how to read in school, not much else that happens there is going to matter.

This might be a harsh way of putting it, but it’s the truth. Being unable to read makes it nearly impossible to function in society. Reading is foundational to everything, even mathematics.

That’s why Canadians across the country should be paying attention to what’s happening in Manitoba’s Evergreen School Division. Located in the Interlake region, including communities like Gimli, Arborg and Winnipeg Beach, Evergreen has completely overhauled its approach to reading instruction—and the early results are promising.

Instead of continuing with costly and ineffective methods like Reading Recovery and balanced literacy, Evergreen has adopted a structured literacy approach, putting phonics back at the centre of reading instruction.

Direct and explicit phonics instruction teaches students how to sound out the letters in words. Rather than guessing words from pictures or context, children are taught to decode the language itself. It’s simple, evidence-based, and long overdue.

In just one year, Evergreen schools saw measurable gains. A research firm evaluating the program found that five per cent more kindergarten to Grade 6 students were reading at grade level than the previous year. For a single year of change, that’s a significant improvement.

This should not be surprising. The science behind phonics instruction has been clear for decades. In the 1960s, Dr. Jeanne Chall, director of the Harvard Reading Laboratory, conducted extensive research into reading methods and concluded that systematic phonics instruction produces the strongest results.

Today, this evidence-based method is often referred to as the “science of reading” because the evidence overwhelmingly supports its effectiveness. While debates continue in many areas of education, this one is largely settled. Students need to be explicitly taught how to read using phonics—and the earlier, the better.

Yet Evergreen stands nearly alone. Manitoba’s Department of Education does not mandate phonics in its public schools. In fact, it largely avoids taking a stance on the issue at all. This silence is a disservice to students—and it’s a missed opportunity for genuine reform.

At the recent Manitoba School Boards Association convention, Evergreen trustees succeeded in passing an emergency motion calling on the association to lobby education faculties to ensure that new teachers are trained in systematic phonics instruction. It’s a critical first step—and one that should be replicated in every province.

It’s a travesty that the most effective reading method isn’t even taught in many teacher education programs. If new teachers aren’t trained in phonics, they’ll struggle to teach their students how to read—and the cycle of failure will continue.

Imagine what could happen if every province implemented structured literacy from the start of Grade 1. Students would become strong readers earlier, be better equipped for all other subjects, and experience greater success throughout school. Early literacy is a foundation for lifelong learning.

Evergreen School Division deserves credit for following the evidence and prioritizing real results over educational trends. But it shouldn’t be alone in this.

If provinces across Canada want to raise literacy rates and give every child a fair shot at academic success, they need to follow Evergreen’s lead—and they need to do it now.

All students deserve to learn how to read.

Michael Zwaagstra is a public high school teacher and a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Economy

Support For National Pipelines And LNG Projects Gain Momentum, Even In Quebec

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Public opinion on pipelines has shifted. Will Ottawa seize the moment for energy security or let politics stall progress?

The ongoing threats posed by U.S. tariffs on the Canadian economy have caused many Canadians to reconsider the need for national oil pipelines and other major resource projects.

The United States is Canada’s most significant trading partner, and the two countries have enjoyed over a century of peaceful commerce and good relations. However, the onset of tariffs and increasingly hostile rhetoric has made Canadians realize they should not be taking these good relations for granted.

Traditional opposition to energy development has given way to a renewed focus on energy security and domestic self-reliance. Over the last decade, Canadian energy producers have sought to build pipelines to move oil from landlocked Alberta to tidewater, aiming to reduce reliance on U.S. markets and expand exports internationally. Canada’s dependence on the U.S. for energy exports has long affected the prices it can obtain.

One province where this shift is becoming evident is Quebec. Historically, Quebec politicians and environmental interests have vehemently opposed oil and gas development. With an abundance of hydroelectric power, imported oil and gas, and little fossil fuel production, the province has had fewer economic incentives to support the industry.

However, recent polling suggests attitudes are changing. A SOM-La Presse poll from late February found that about 60 per cent of Quebec residents support reviving the Energy East pipeline project, while 61 per cent favour restarting the GNL Quebec natural gas pipeline project, a proposed LNG facility near Saguenay that would export liquefied natural gas to global markets. While support for these projects remains stronger in other parts of the country, this represents a substantial shift in Quebec.

Yet, despite this change, Quebec politicians at both the provincial and federal levels remain out of step with public opinion. The Montreal Economic Institute, a non-partisan think tank, has documented this disconnect for years. There are two key reasons for it: Quebec politicians tend to reflect the perspectives of a Montreal-based Laurentian elite rather than broader provincial sentiment, and entrenched interests such as Hydro-Québec benefit from limiting competition under the guise of environmental concerns.

Not only have Quebec politicians misrepresented public opinion, but they have also claimed to speak for the entire province on energy issues. Premier François Legault and Bloc Québécois Leader Yves-François Blanchet have argued that pipeline projects lack “social licence” from Quebecers.

However, the reality is that the federal government does not need any special license to build oil and gas infrastructure that crosses provincial borders. Under the Constitution, only the federal Parliament has jurisdiction over national pipeline and energy projects.

Despite this authority, no federal government has been willing to impose such a project on a province. Quebec’s history of resisting federal intervention makes this a politically delicate issue. There is also a broader electoral consideration: while it is possible to form a federal government without winning Quebec, its many seats make it a crucial battleground. In a bilingual country, a government that claims to speak for all Canadians benefits from having a presence in Quebec.

Ottawa could impose a national pipeline, but it doesn’t have to. New polling data from Quebec and across Canada suggest Canadians increasingly support projects that enhance energy security and reduce reliance on the United States. The federal government needs to stop speaking only to politicians—especially in Quebec—and take its case directly to the people.

With a federal election on the horizon, politicians of all parties should put national pipelines and natural gas projects on the ballot.

Joseph Quesnel is a senior research fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

-

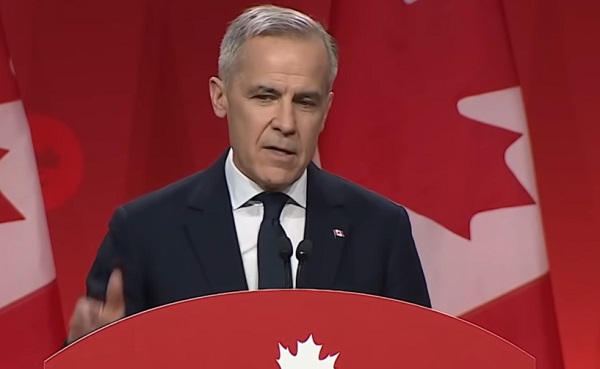

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoRCMP Whistleblowers Accuse Members of Mark Carney’s Inner Circle of Security Breaches and Surveillance

-

Also Interesting2 days ago

Also Interesting2 days agoBetFury Review: Is It the Best Crypto Casino?

-

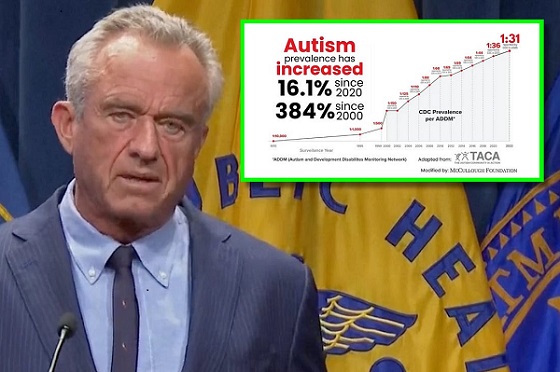

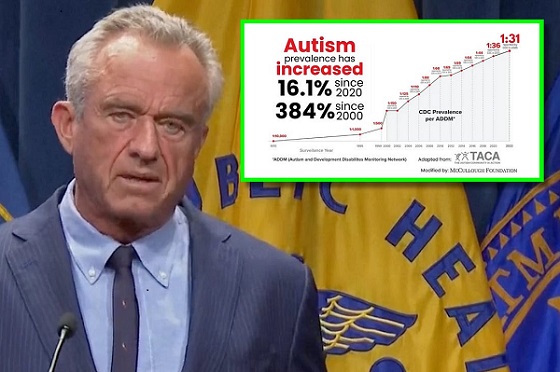

Autism2 days ago

Autism2 days agoRFK Jr. Exposes a Chilling New Autism Reality

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoCanadian student denied religious exemption for COVID jab takes tech school to court

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoBureau Exclusive: Chinese Election Interference Network Tied to Senate Breach Investigation

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoUK Supreme Court rules ‘woman’ means biological female

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoNeil Young + Carney / Freedom Bros

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoWHO member states agree on draft of ‘pandemic treaty’ that could be adopted in May