Health

Province & Doctors Ratify New Agreement

By Sheldon Spackman

The Alberta Government has announced the ratification of an amending agreement between the province and it’s physicians that aims to improve patient care. However, the amending agreement still needs to be signed by both parties.

Government officials say the voting process for Alberta Medical Association (AMA) members started six weeks ago with the final count showing that 74 per cent of voting physicians were in favour of amending the existing 2011-18 master agreement.

Minister of Health Sarah Hoffman says “We thank Alberta’s physicians for their support of these amendments and their dedication and commitment to improving the health and well-being of all Albertans. As shared stewards of our health system, we now look forward to working together on changes that will improve accessibility to high-quality care and keep the health system sustainable in the long term.”

Alberta Medical Association President Dr. Padriac Carr says “In ratifying this agreement, physicians and government are moving in positive new directions. We will work to moderate the rate of expenditure growth while maintaining quality care and providing greater value for patients. The amending agreement will also contribute to a higher level of integration and increased efficiency in the system in the long term.”

The ratified amendments come after six months of negotiations and are based on a tentative agreement announced Aug. 31. The agreement, which recognizes a shared responsibility to provide quality health care in a financially sustainable framework, is expected to improve patient care and significantly slow the growth of health-care spending by the end of 2018.

Highlights of the amending agreement include a needs-based Physician Resource Plan that will help place doctors in the communities that need them. Primary care improvements, including new information technology and data-sharing. New compensation models for some primary-care physicians, as well as academic physicians, to reward time and quality of care given to patients rather than just the number of services provided. New physician peer review and accountability mechanisms and the linking of certain benefits and compensation increases to performance on other cost-saving measures.

The current master agreement with physicians will now be amended. The government and the AMA will immediately start negotiations on the overall master agreement that expires in 2018.

Business

Cutting Red Tape Could Help Solve Canada’s Doctor Crisis

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Ian Madsen

Doctors waste millions of hours on useless admin. It’s enough to end Canada’s doctor shortage. Ian Madsen says slashing red tape, not just recruiting, is the fastest fix for the clogged system.

Doctors spend more time on paperwork than on patients and that’s fueling Canada’s health care wait lists

Canada doesn’t just lack doctors—it squanders the ones it has. Mountains of paperwork and pointless admin chew up tens of millions of physician hours every year, time that could erase the so-called shortage and slash wait lists if freed for patient care.

Recruiting more doctors helps, but the fastest cure for our sick system is cutting the bureaucracy that strangles the ones already here.

The Canadian Medical Association found that unnecessary non-patient work consumes millions of hours annually. That’s the equivalent of 50.5 million patient visits, enough to give every Canadian at least one appointment and likely erase the physician shortage. Meanwhile, the Canadian Institute for Health Information estimates more than six million Canadians don’t even have a family doctor. That’s roughly one in six of us.

And it’s not just patients who feel the shortage—doctors themselves are paying the price. Endless forms don’t just waste time; they drive doctors out of the profession. Burned out and frustrated, many cut their hours or leave entirely. And the foreign doctors that health authorities are trying to recruit? They might think twice once they discover how much time Canadian physicians spend on paperwork that adds nothing to patient care.

But freeing doctors from forms isn’t as simple as shredding them. Someone has to build systems that reduce, rather than add to, the workload. And that’s where things get tricky. Trimming red tape usually means more Information Technology (IT), and big software projects have a well-earned reputation for spiralling in cost.

Bent Flyvbjerg, the global guru of project disasters, and his colleagues examined more than 5,000 IT projects in a 2022 study. They found outcomes didn’t follow a neat bell curve but a “power-law” distribution, meaning costs don’t just rise steadily, they explode in a fat tail of nasty surprises as variables multiply.

Oxford University and McKinsey offered equally bleak news. Their joint study concluded: “On average, large IT projects run 45 per cent over budget and seven per cent over time while delivering 56 per cent less value than predicted.” If that sounds familiar, it should. Canada’s Phoenix federal payroll fiasco—the payroll software introduced by Ottawa that left tens of thousands of federal workers underpaid or unpaid—is a cautionary tale etched into the national memory.

The lesson isn’t to avoid technology, but to get it right. Canada can’t sidestep the digital route. The question is whether we adapt what others have built or design our own. One option is borrowing from the U.S. or U.K., where electronic health record (EHR) systems (the digital patient files used by doctors and hospitals) are already in place. Both countries have had headaches with their systems, thanks to legal and regulatory differences. But there are signs of progress.

The U.K. is experimenting with artificial intelligence to lighten the administrative load, and a joint U.K.-U.S. study gives a glimpse of what’s possible:

“… AI technologies such as Robotic Process Automation (RPA), predictive analytics, and Natural Language Processing (NLP) are transforming health care administration. RPA and AI-driven software applications are revolutionizing health care administration by automating routine tasks such as appointment scheduling, billing, and documentation. By handling repetitive, rule-based tasks with speed and accuracy, these technologies minimize errors, reduce administrative burden, and enhance overall operational efficiency.”

For patients, that could mean fewer missed referrals, faster follow-up calls and less time waiting for paperwork to clear before treatment. Still, even the best tools come with limits. Systems differ, and customization will drive up costs. But medicine is medicine, and AI tools can bridge more gaps than you might think.

Run the math. If each “freed” patient visit is worth just $20—a conservative figure for the value of a basic appointment—the payoff could hit $1 billion in a single year.

Updating costs would continue, but that’s still cheap compared to the human and financial toll of endless wait lists. Cost-sharing between provinces, Ottawa, municipalities and even doctors themselves could spread the risk. Competitive bidding, with honest budgets and realistic timelines, is non-negotiable if we want to dodge another Phoenix-sized fiasco.

The alternative—clinging to our current dysfunctional patchwork of physician information systems—isn’t really an option. It means more frustrated doctors walking away, fewer new ones coming in, and Canadians left to languish on wait lists that grow ever longer.

And that’s not health care—it’s managed decline.

Ian Madsen is a senior policy analyst at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Addictions

BC premier admits decriminalizing drugs was ‘not the right policy’

From LifeSiteNews

Premier David Eby acknowledged that British Columbia’s liberal policy on hard drugs ‘became was a permissive structure that … resulted in really unhappy consequences.’

The Premier of Canada’s most drug-permissive province admitted that allowing the decriminalization of hard drugs in British Columbia via a federal pilot program was a mistake.

Speaking at a luncheon organized by the Urban Development Institute last week in Vancouver, British Columbia, Premier David Eby said, “I was wrong … it was not the right policy.”

Eby said that allowing hard drug users not to be fined for possession was “not the right policy.

“What it became was a permissive structure that … resulted in really unhappy consequences,” he noted, as captured by Western Standard’s Jarryd Jäger.

LifeSiteNews reported that the British Columbia government decided to stop a so-called “safe supply” free drug program in light of a report revealing many of the hard drugs distributed via pharmacies were resold on the black market.

Last year, the Liberal government was forced to end a three-year drug decriminalizing experiment, the brainchild of former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government, in British Columbia that allowed people to have small amounts of cocaine and other hard drugs. However, public complaints about social disorder went through the roof during the experiment.

This is not the first time that Eby has admitted he was wrong.

Trudeau’s loose drug initiatives were deemed such a disaster in British Columbia that Eby’s government asked Trudeau to re-criminalize narcotic use in public spaces, a request that was granted.

Records show that the Liberal government has spent approximately $820 million from 2017 to 2022 on its Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy. However, even Canada’s own Department of Health in a 2023 report admitted that the Liberals’ drug program only had “minimal” results.

Official figures show that overdoses went up during the decriminalization trial, with 3,313 deaths over 15 months, compared with 2,843 in the same time frame before drugs were temporarily legalized.

-

Alberta21 hours ago

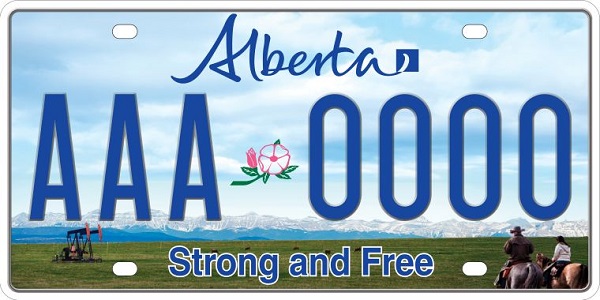

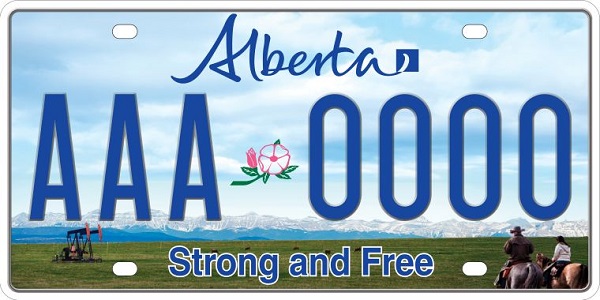

Alberta21 hours agoClick here to help choose Alberta’s new licence plate design

-

National22 hours ago

National22 hours agoDemocracy Watch Renews Push for Independent Prosecutor in SNC-Lavalin Case

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoPoland’s president signs new zero income tax law for parents with two children

-

Business23 hours ago

Business23 hours agoOver two thirds of Canadians say Ottawa should reduce size of federal bureaucracy

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days ago$15 Billion, Zero Assurances: Stellantis Abandons Brampton as Trudeau-Era Green Deal Collapses

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoTrump Admin Blows Up UN ‘Global Green New Scam’ Tax Push, Forcing Pullback

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoTrump Blocks UN’s Back Door Carbon Tax

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoPoilievre accuses Canada’s top police force of ‘covering up’ alleged Trudeau crimes