Opinion

Ponoka’s Muliplex is a go,adding to Penhold, Blackfalds, and Lacombe to bolster recreation in Central Alberta. Where’s Red Deer?

Ponoka Multiplex is going ahead. Ponoka, population 7,229, is going to spend $16.6 million or $2,296 per person on a recreational multiplex, to service residents and attract growth. Great news.

Penhold Multiplex was a huge success in both regards. Penhold, population 3,277 spent $23 million or $7,018 per person and the town grew and they needed more land.

Blackfalds spent $15.2 million on the Abbey Centre and are looking to spend another $12 million on a second covered ice rink, for a total of $27.2 million. Blackfalds population 9328, will be spending $2,916 per resident on recreation.

Sylvan Lake has the new Nexsource Centre multiplex. Sylvan Lake, population 14,816 spent $33.5 million or $2,264 per person on a recreational complex.

Lacombe is spending $13,668,141 upgrading their sports complex. Lacombe population 13,057 means $1,047 per person for upgrading.

This means that 47,700 people are putting out $102 million for recreation complexes. These are growing communities looking to attract more growth. This growth has been partially from Red Deer residents migrating away from Red Deer. Red Deer’s population shrank between 2015-2016. Their own polls shows they shrank by a 1,000 residents but the federal census puts it only 400 residents less. The area north of the river shrank by 777 residents alone. There are still about 30,000 residents living north of the river.

They have only one recreational complex, over 30 years old. If the city was to step up to the plate and treat the residents on par with the smaller communities they would need to spend $64 million on recreational facilities north of the river.

If the city as a whole wanted to be equal to these smaller communities then they would have to spend $214 million dollars on recreational facilities. To compare with Penhold, the city would have to spend $700 million but Blackfalds is one of the fastest growing communities in Canada. To match their per capita spending the city of Red Deer would have to commit $292 million on recreational facilities.

Lethbridge, the third fastest growing city in Alberta and nearest in size to Red Deer recently committed $109 million for phase 2 of their recreation centre. Again to attract young families, a necessity for growth. Remember Lethbridge once turned a man-made slough into a lake and created Henderson Lake Park around it. It may be why they are the 5th fastest growing city in Canada behind Regina, Saskatoon, Edmonton and Calgary.

Red Deer was once a hub for Central Alberta, now it cannot keep pace with Penhold, Blackfalds, Ponoka, Lacombe, Sylvan Lake, as they grow and seek out new possibilities.

The last big project in Red Deer was the Collicutt Center in Red Deer’s south east, that was 15 years ago and the city grew, that area developed, and noone is saying now that the Collicutt Centre was a bad idea.

We are opening up land in the northwest corner, thousands of acres, room for 25,000 residents and Red Deer’s largest lake, Hazlett Lake. 55,000 residents north of the river, the same population as when they decided to build a 4th recreational centre now known as the Collicutt Centre.

Red Deer needs to build a 50m pool, and the north side needs new recreational facilities, and our Collicutt Centre was such a huge success in spurring growth, why not build a Northside Collicutt Centre with a 50m pool and ice rink on Hazlett Lake?

Red Deer could be a sports hub, a tourist hub and an economic hub, once again. The proof is t5here, we just need the courage. If we do not have it now maybe we can find it before the municipal election this coming October. We just need to ask. I am asking but I am getting the run around, which could be why everyone else is growing and we are shrinking. What do you think? Let me know. Thank you.

Freedom Convoy

Court Orders Bank Freezing Records in Freedom Convoy Case

|

A Canadian court has ordered the release of documents that could shed light on how federal authorities and law enforcement worked together to freeze the bank accounts of a protester involved in the Freedom Convoy.

Both the RCMP and TD Bank are now required to provide records related to Evan Blackman, who took part in the 2022 demonstrations and had his accounts frozen despite not being convicted of any crime at the time.

The Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms (JCCF) announced the Ontario Court of Justice ruling. The organization is representing Blackman, whose legal team argues that the actions taken against him amounted to a serious abuse of power.

“The freezing of Mr. Blackman’s bank accounts was an extreme overreach on the part of the police and the federal government,” said his lawyer, Chris Fleury. “These records will hopefully reveal exactly how and why Mr. Blackman’s accounts [were] frozen.”

Blackman was arrested during the mass protests in Ottawa, which drew thousands of Canadians opposed to vaccine mandates and other pandemic-era restrictions.

Although he faced charges of mischief and obstructing police, those charges were dismissed in October due to a lack of evidence. Despite this, prosecutors have appealed, and a trial is set to begin on August 14.

At the height of the protests, TD Bank froze three of Blackman’s accounts following government orders issued under the Emergencies Act. Then-Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had invoked the act to grant his government broad powers to disrupt the protest movement, including the unprecedented use of financial institutions to penalize individuals for their support or participation.

In 2024, a Federal Court Justice ruled that Trudeau’s decision to invoke the act had not been justified.

Blackman’s legal team plans to use the newly released records to demonstrate the extent of government intrusion into personal freedoms.

According to the JCCF, this case may be the first in Canada where a criminal trial includes a Charter challenge over the freezing of personal bank accounts under emergency legislation.

|

Alberta

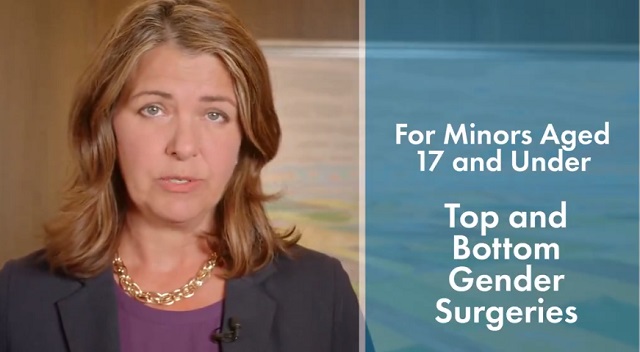

‘Far too serious for such uninformed, careless journalism’: Complaint filed against Globe and Mail article challenging Alberta’s gender surgery law

Macdonald Laurier Institute challenges Globe article on gender medicine

The complaint, now endorsed by 41 physicians, was filed in response to an article about Alberta’s law restricting gender surgery and hormones for minors.

On June 9, the Macdonald-Laurier Institute submitted a formal complaint to The Globe and Mail regarding its May 29 Morning Update by Danielle Groen, which reported on the Canadian Medical Association’s legal challenge to Alberta’s Bill 26.

Written by MLI Senior Fellow Mia Hughes and signed by 34 Canadian medical professionals at the time of submission to the Globe, the complaint stated that the Morning Update was misleading, ideologically slanted, and in violation the Globe’s own editorial standards of accuracy, fairness, and balance. It objected to the article’s repetition of discredited claims—that puberty blockers are reversible, that they “buy time to think,” and that denying access could lead to suicide—all assertions that have been thoroughly debunked in recent years.

Given the article’s reliance on the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), the complaint detailed the collapse of WPATH’s credibility, citing unsealed discovery documents from an Alabama court case and the Cass Review’s conclusion that WPATH’s guidelines—and those based on them—lack developmental rigour. It also noted the newsletter’s failure to mention the growing international shift away from paediatric medical transition in countries such as the UK, Sweden, and Finland. MLI called for the article to be corrected and urged the Globe to uphold its commitment to balanced, evidence-based journalism on this critical issue.

On June 18, Globe and Mail Standards Editor Sandra Martin responded, defending the article as a brief summary that provided a variety of links to offer further context. However, the three Globe and Mail news stories linked to in the article likewise lacked the necessary balance and context. Martin also pointed to a Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) statement linked to in the newsletter. She argued it provided “sufficient context and qualification”—despite the fact that the CPS itself relies on WPATH’s discredited guidelines. Notwithstanding, Martin claimed the article met editorial standards and that brevity justified the lack of balance.

MLI responded that brevity does not excuse misinformation, particularly on a matter as serious as paediatric medical care, and reiterated the need for the Globe to address the scientific inaccuracies directly. MLI again called for the article to be corrected and for the unsupported suicide claim to be removed. As of this writing, the Globe has not responded.

Letter of complaint

June 9, 2025

To: The Globe and Mail

Attn: Sandra Martin, standards editor

CC: Caroline Alphonso, health editor; Mark Iype, deputy national editor and Alberta bureau chief

To the editors;

Your May 29 Morning Update: The Politics of Care by Danielle Groen, covering the Canadian Medical Association’s legal challenge to Alberta’s Bill 26, was misleading and ideologically slanted. It is journalistically irresponsible to report on contested medical claims as undisputed fact.

This issue is far too serious for such uninformed, careless journalism lacking vital perspectives and scientific context. At stake is the health and future of vulnerable children, and your reporting risks misleading parents into consenting to irreversible interventions based on misinformation.

According to The Globe and Mail’s own Journalistic Principles outlined in its Editorial Code of Conduct, the credibility of your reporting rests on “solid research, clear, intelligent writing, and maintaining a reputation for honesty, accuracy, fairness, balance and transparency.” Moreover, your principles go on to state that The Globe will “seek to provide reasonable accounts of competing views in any controversy.” The May 29 update violated these principles. There is, as I will show, a widely available body of scientific information that directly contests the claims and perspectives presented in your article. Yet this information is completely absent from your reporting.

The collapse of WPATH’s credibility

The article’s claim that Alberta’s law “falls well outside established medical practice” and could pose the “greatest threat” to transgender youth is both false and inflammatory. There is no global medical consensus on how to treat gender-distressed young people. In fact, in North America, guidelines are based on the Standards of Care developed by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH)—an organization now indisputably shown to place ideology above evidence.

For example, in a U.S. legal case over Alabama’s youth transition ban, WPATH was forced to disclose over two million internal emails. These revealed the organization commissioned independent evidence reviews for its latest Standards of Care (SOC8)—then suppressed those reviews when they found overwhelmingly low-quality evidence. Yet WPATH proceeded to publish the SOC8 as if it were evidence-based. This is not science. It is fraudulent and unethical conduct.

These emails also showed Admiral Rachel Levine—then-assistant secretary for Health in the Biden administration—pressured WPATH to remove all lower age recommendations from the guidelines—not on scientific grounds, but to avoid undermining ongoing legal cases at the state level. This is politics, not sound medical practice.

The U.K.’s Cass Review, a major multi-year investigation, included a systematic review of the guidelines in gender medicine. A systematic review is considered the gold standard because it assesses and synthesizes all the available research in a field, thereby reducing bias and providing a large comprehensive set of data upon which to reach findings. The systematic review of gender medicine guidelines concluded that WPATH’s standards of care “lack developmental rigour” and should not be used as a basis for clinical practice. The Cass Review also exposed citation laundering where medical associations endlessly recycled weak evidence across interlocking guidelines to fabricate a false consensus. This led Cass to suggest that “the circularity of this approach may explain why there has been an apparent consensus on key areas of practice despite the evidence being poor.”

Countries like Sweden, Finland, and the U.K. have now abandoned WPATH and limited or halted medicalized youth transitions in favour of a therapy-first approach. In Norway, UKOM, an independent government health agency, has made similar recommendations. This shows the direction of global practice is moving away from WPATH’s medicalized approach—not toward it. As part of any serious effort to “provide reasonable accounts of competing views,” your reporting should acknowledge these developments.

Any journalist who cites WPATH as a credible authority on paediatric gender medicine—especially in the absence of contextualizing or competing views—signals a lack of due diligence and a fundamental misunderstanding of the field. It demonstrates that either no independent research was undertaken, or it was ignored despite your editorial standards.

Puberty blockers don’t ‘buy time’ and are not reversible

Your article repeats a widely debunked claim: that puberty blockers are a harmless pause to allow young people time to explore their identity. In fact, studies have consistently shown that between 98 per cent and 100 per cent of children placed on puberty blockers go on to take cross-sex hormones. Before puberty blockers, most children desisted and reconciled with their birth sex during or after puberty. Now, virtually none do.

This strongly suggests that blocking puberty in fact prevents the natural resolution of gender distress. Therefore, the most accurate and up-to-date understanding is that puberty blockers function not as a pause, but as the first step in a treatment continuum involving irreversible cross-sex hormones. Indeed, a 2022 paper found that while puberty suppression had been “justified by claims that it was reversible … these claims are increasingly implausible.” Again, adherence to the Globe’s own editorial guidelines would require, at minimum, the acknowledgement of the above findings alongside the claims your May 29 article makes.

Moreover, it is categorically false to describe puberty blockers as “completely reversible.” Besides locking youth into a pathway of further medicalization, puberty blockers pose serious physical risks: loss of bone density, impaired sexual development, stunted fertility, and psychosocial harm from being developmentally out of sync with peers. There are no long-term safety studies. These drugs are being prescribed to children despite glaring gaps in our understanding of their long-term effects.

Given the Globe’s stated editorial commitment to principles such as “accuracy,” the crucial information from the studies linked above should be provided in any article discussing puberty blockers. At a bare minimum, in adherence to the Globe’s commitment to “balance,” this information should be included alongside the contentious and disputed claims the article makes that these treatments are reversible.

No proof of suicide prevention

The most irresponsible and dangerous claim in your article is that denying access to puberty blockers could lead to “depression, self-harm and suicide.” There is no robust evidence supporting this transition-or-suicide narrative, and in fact, the findings of the highest-quality study conducted to date found no evidence that puberty suppression reduces suicide risk.

Suicide is complex and attributing it to a single cause is not only false—it violates all established suicide reporting guidelines. Sensationalized claims like this risk creating contagion effects and fuelling panic. In the public interest, reporting on the topic of suicide must be held to the most rigorous standards, and provide the most high-quality and accurate information.

Euphemism hides medical harm

Your use of euphemistic language obscures the extreme nature of the medical interventions being performed in gender clinics. Calling double mastectomies for teenage girls “paediatric breast surgeries for gender-affirming reasons” sanitizes the medically unnecessary removal of a child’s healthy organs. Referring to phalloplasty and vaginoplasty as “gender-affirming surgeries on lower body parts” conceals the fact that these are extreme operations involving permanent disfigurement, high complication rates, and often requiring multiple revisions.

Honest journalism should not hide these facts behind comforting language. Your reporting denies youth, their parents, and the general public the necessary information to understand the nature of these interventions. Members of the general public rely greatly on the news media to equip them with such information, and your own editorial standards claim you will fulfill this core responsibility.

Your responsibility to the public

As a flagship Canadian news outlet, your responsibility is not to amplify activist messaging, but to report the truth with integrity. On a subject as medically and ethically fraught as paediatric gender medicine, accuracy is not optional. The public depends on you to scrutinize claims, not echo ideology. Parents may make irreversible decisions on behalf of their children based on the narratives you promote. When reporting is false or ideologically distorted, the cost is measured in real-world harm to some of our society’s most vulnerable young people.

I encourage the Globe and Mail to publish an updated version on this article in order to correct the public record with the relevant information discussed above, and to modify your reporting practices on this matter going forward—by meeting your own journalistic standards—so that the public receives balanced, correct, and reliable information on this vital topic.

Trustworthy journalism is a cornerstone of public health—and on the issue of paediatric gender medicine, the stakes could not be higher.

Sincerely,

Mia Hughes

Senior Fellow, Macdonald-Laurier Institute

Author of The WPATH Files

The following 41 physicians have signed to endorse this letter:

Dr. Mike Ackermann, MD

Dr. Duncan Veasey, Psy MD

Dr. Rick Gibson, MD

Dr. Benjamin Turner, MD, FRCSC

Dr. J.N. Mahy, MD, FRCSC, FACS

Dr. Khai T. Phan, MD, CCFP

Dr. Martha Fulford, MD

Dr. J. Edward Les, MD, FRCPC

Dr. Darrell Palmer, MD, FRCPC

Dr. Jane Cassie, MD, FRCPC

Dr. David Lowen, MD, FCFP

Dr. Shawn Whatley, MD, FCFP (EM)

Dr. David Zitner, MD

Dr. Leonora Regenstreif, MD, CCFP(AM), FCFP

Dr. Gregory Chan, MD

Dr. Alanna Fitzpatrick, MD, FRCSC

Dr. Chris Millburn, MD, CCFP

Dr. Julie Curwin, MD, FRCPC

Dr. Roy Eappen, MD, MDCM, FRCP (c)

Dr. York N. Hsiang, MD, FRCSC

Dr. Dion Davidson, MD, FRCSC, FACS

Dr. Kevin Sclater, MD, CCFP (PC)

Dr. Theresa Szezepaniak, MB, ChB, DRCOG

Dr. Sofia Bayfield, MD, CCFP

Dr. Elizabeth Henry, MD, CCFP

Dr. Stephen Malthouse, MD

Dr. Darrell Hamm, MD, CCFP

Dr. Dale Classen, MD, FRCSC

Dr. Adam T. Gorner, MD, CCFP

Dr. Wesley B. Steed, MD

Dr. Timothy Ehmann, MD, FRCPC

Dr. Ryan Torrie, MD

Dr. Zachary Heinricks, MD, CCFP

Dr. Jessica Shintani, MD, CCFP

Dr. Mark D’Souza, MD, CCFP(EM), FCFP*

Dr. Joanne Sinai, MD, FRCPC*

Dr. Jane Batt, MD*

Dr. Brent McGrath, MD, FRCPC*

Dr. Leslie MacMillan MD FRCPC (emeritus)*

Dr. Ian Mitchell, MD, FRCPC*

Dr. John Cunnington, MD

*Indicates physician who signed following the letter’s June 9 submission to the Globe and Mail, but in advance of this letter being published on the MLI website.

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day ago“This is a total fucking disaster”

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoChicago suburb purchases childhood home of Pope Leo XIV

-

Fraser Institute1 day ago

Fraser Institute1 day agoBefore Trudeau average annual immigration was 617,800. Under Trudeau number skyrocketted to 1.4 million annually

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoBlackouts Coming If America Continues With Biden-Era Green Frenzy, Trump Admin Warns

-

MAiD1 day ago

MAiD1 day agoCanada’s euthanasia regime is already killing the disabled. It’s about to get worse

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days ago‘I Know How These People Operate’: Fmr CIA Officer Calls BS On FBI’s New Epstein Intel

-

Red Deer1 day ago

Red Deer1 day agoJoin SPARC in spreading kindness by July 14th

-

Economy1 day ago

Economy1 day agoThe stars are aligning for a new pipeline to the West Coast