Health

Pick up 2024 Red Deer Hospital Lottery tickets to be eligible for Previous Supporter Draws

Red Deer Hospital Lottery opens the 2024 Dream Home by Sorento Custom Homes April 12, 2024!

The dream home prize package is valued at $1,072,624.00 and includes furnishings and

accessories from Urban Barn.

Other prizes in the lottery this year include a Tree Hugger Tiny Home prize package valued at

$163,798.00, on display at the Red Deer Hospital beginning April 10th, two Early Bird cash prizes,

and electronics. The total prize value is over $1.29 million.

Proceeds from the 2024 Hospital Lottery and Mega Bucks 50 will contribute to acquiring critically needed, state-of-the-art equipment in several units at the Red Deer Hospital.

Don’t miss out on your exclusive chance to win in our Previous Supporter Draws – 5 cash prizes of $1,000 each! But there are only a few days left! Purchase your tickets before 11:59pm on April 11th to be eligible for the Previous Supporter Draws, and over $1.29 million in prizes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alberta

A Christmas wish list for health-care reform

From the Fraser Institute

By Nadeem Esmail and Mackenzie Moir

It’s an exciting time in Canadian health-care policy. But even the slew of new reforms in Alberta only go part of the way to using all the policy tools employed by high performing universal health-care systems.

For 2026, for the sake of Canadian patients, let’s hope Alberta stays the path on changes to how hospitals are paid and allowing some private purchases of health care, and that other provinces start to catch up.

While Alberta’s new reforms were welcome news this year, it’s clear Canada’s health-care system continued to struggle. Canadians were reminded by our annual comparison of health care systems that they pay for one of the developed world’s most expensive universal health-care systems, yet have some of the fewest physicians and hospital beds, while waiting in some of the longest queues.

And speaking of queues, wait times across Canada for non-emergency care reached the second-highest level ever measured at 28.6 weeks from general practitioner referral to actual treatment. That’s more than triple the wait of the early 1990s despite decades of government promises and spending commitments. Other work found that at least 23,746 patients died while waiting for care, and nearly 1.3 million Canadians left our overcrowded emergency rooms without being treated.

At least one province has shown a genuine willingness to do something about these problems.

The Smith government in Alberta announced early in the year that it would move towards paying hospitals per-patient treated as opposed to a fixed annual budget, a policy approach that Quebec has been working on for years. Albertans will also soon be able purchase, at least in a limited way, some diagnostic and surgical services for themselves, which is again already possible in Quebec. Alberta has also gone a step further by allowing physicians to work in both public and private settings.

While controversial in Canada, these approaches simply mirror what is being done in all of the developed world’s top-performing universal health-care systems. Australia, the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland all pay their hospitals per patient treated, and allow patients the opportunity to purchase care privately if they wish. They all also have better and faster universally accessible health care than Canada’s provinces provide, while spending a little more (Switzerland) or less (Australia, Germany, the Netherlands) than we do.

While these reforms are clearly a step in the right direction, there’s more to be done.

Even if we include Alberta’s reforms, these countries still do some very important things differently.

Critically, all of these countries expect patients to pay a small amount for their universally accessible services. The reasoning is straightforward: we all spend our own money more carefully than we spend someone else’s, and patients will make more informed decisions about when and where it’s best to access the health-care system when they have to pay a little out of pocket.

The evidence around this policy is clear—with appropriate safeguards to protect the very ill and exemptions for lower-income and other vulnerable populations, the demand for outpatient healthcare services falls, reducing delays and freeing up resources for others.

Charging patients even small amounts for care would of course violate the Canada Health Act, but it would also emulate the approach of 100 per cent of the developed world’s top-performing health-care systems. In this case, violating outdated federal policy means better universal health care for Canadians.

These top-performing countries also see the private sector and innovative entrepreneurs as partners in delivering universal health care. A relationship that is far different from the limited individual contracts some provinces have with private clinics and surgical centres to provide care in Canada. In these other countries, even full-service hospitals are operated by private providers. Importantly, partnering with innovative private providers, even hospitals, to deliver universal health care does not violate the Canada Health Act.

So, while Alberta has made strides this past year moving towards the well-established higher performance policy approach followed elsewhere, the Smith government remains at least a couple steps short of truly adopting a more Australian or European approach for health care. And other provinces have yet to even get to where Alberta will soon be.

Let’s hope in 2026 that Alberta keeps moving towards a truly world class universal health-care experience for patients, and that the other provinces catch up.

Alberta

Alberta’s new diagnostic policy appears to meet standard for Canada Health Act compliance

From the Fraser Institute

By Nadeem Esmail, Mackenzie Moir and Lauren Asaad

In October, Alberta’s provincial government announced forthcoming legislative changes that will allow patients to pay out-of-pocket for any diagnostic test they want, and without a physician referral. The policy, according to the Smith government, is designed to help improve the availability of preventative care and increase testing capacity by attracting additional private sector investment in diagnostic technology and facilities.

Unsurprisingly, the policy has attracted Ottawa’s attention, with discussions now taking place around the details of the proposed changes and whether this proposal is deemed to be in line with the Canada Health Act (CHA) and the federal government’s interpretations. A determination that it is not, will have both political consequences by being labeled “non-compliant” and financial consequences for the province through reductions to its Canada Health Transfer (CHT) in coming years.

This raises an interesting question: While the ultimate decision rests with Ottawa, does the Smith government’s new policy comply with the literal text of the CHA and the revised rules released in written federal interpretations?

According to the CHA, when a patient pays out of pocket for a medically necessary and insured physician or hospital (including diagnostic procedures) service, the federal health minister shall reduce the CHT on a dollar-for-dollar basis matching the amount charged to patients. In 2018, Ottawa introduced the Diagnostic Services Policy (DSP), which clarified that the insured status of a diagnostic service does not change when it’s offered inside a private clinic as opposed to a hospital. As a result, any levying of patient charges for medically necessary diagnostic tests are considered a violation of the CHA.

Ottawa has been no slouch in wielding this new policy, deducting some $76.5 million from transfers to seven provinces in 2023 and another $72.4 million in 2024. Deductions for Alberta, based on Health Canada’s estimates of patient charges, totaled some $34 million over those two years.

Alberta has been paid back some of those dollars under the new Reimbursement Program introduced in 2018, which created a pathway for provinces to be paid back some or all of the transfers previously withheld on a dollar-for-dollar basis by Ottawa for CHA infractions. The Reimbursement Program requires provinces to resolve the circumstances which led to patient charges for medically necessary services, including filing a Reimbursement Action Plan for doing so developed in concert with Health Canada. In total, Alberta was reimbursed $20.5 million after Health Canada determined the provincial government had “successfully” implemented elements of its approved plan.

Perhaps in response to the risk of further deductions, or taking a lesson from the Reimbursement Action Plan accepted by Health Canada, the province has gone out of its way to make clear that these new privately funded scans will be self-referred, that any patient paying for tests privately will be reimbursed if that test reveals a serious or life-threatening condition, and that physician referred tests will continue to be provided within the public system and be given priority in both public and private facilities.

Indeed, the provincial government has stated they do not expect to lose additional federal health care transfers under this new policy, based on their success in arguing back previous deductions.

This is where language matters: Health Canada in their latest CHA annual report specifically states the “medical necessity” of any diagnostic test is “determined when a patient receives a referral or requisition from a medical practitioner.” According to the logic of Ottawa’s own stated policy, an unreferred test should, in theory, be no longer considered one that is medically necessary or needs to be insured and thus could be paid for privately.

It would appear then that allowing private purchase of services not referred by physicians does pass the written standard for CHA compliance, including compliance with the latest federal interpretation for diagnostic services.

But of course, there is no actual certainty here. The federal government of the day maintains sole and final authority for interpretation of the CHA and is free to revise and adjust interpretations at any time it sees fit in response to provincial health policy innovations. So while the letter of the CHA appears to have been met, there is still a very real possibility that Alberta will be found to have violated the Act and its interpretations regardless.

In the end, no one really knows with any certainty if a policy change will be deemed by Ottawa to run afoul of the CHA. On the one hand, the provincial government seems to have set the rules around private purchase deliberately and narrowly to avoid a clear violation of federal requirements as they are currently written. On the other hand, Health Canada’s attention has been aroused and they are now “engaging” with officials from Alberta to “better understand” the new policy, leaving open the possibility that the rules of the game may change once again. And even then, a decision that the policy is permissible today is not permanent and can be reversed by the federal government tomorrow if its interpretive whims shift again.

The sad reality of the provincial-federal health-care relationship in Canada is that it has no fixed rules. Indeed, it may be pointless to ask whether a policy will be CHA compliant before Ottawa decides whether or not it is. But it can be said, at least for now, that the Smith government’s new privately paid diagnostic testing policy appears to have met the currently written standard for CHA compliance.

Lauren Asaad

Policy Analyst, Fraser Institute

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoHunting Poilievre Covers For Upcoming Demographic Collapse After Boomers

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoState of the Canadian Economy: Number of publicly listed companies in Canada down 32.7% since 2010

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoCanadian university censors free speech advocate who spoke out against Indigenous ‘mass grave’ hoax

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoHousing in Calgary and Edmonton remains expensive but more affordable than other cities

-

Alberta2 days ago

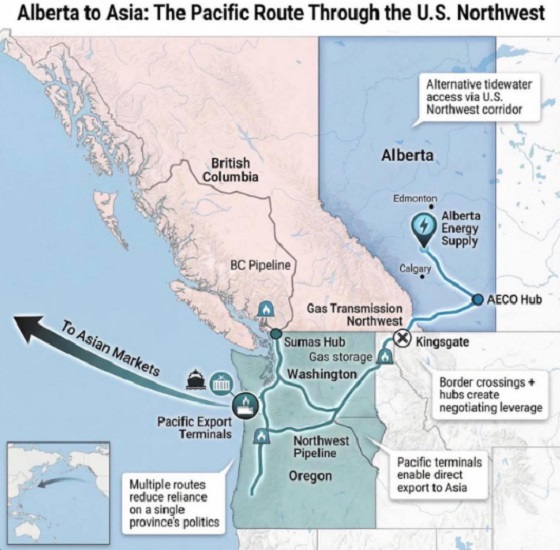

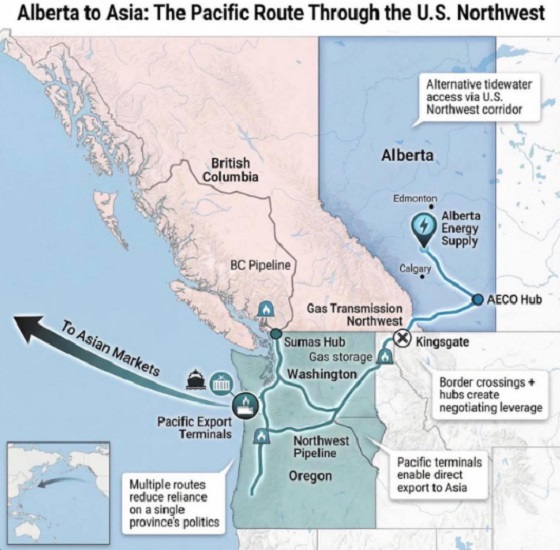

Alberta2 days agoWhat are the odds of a pipeline through the American Pacific Northwest?

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoWarning Canada: China’s Economic Miracle Was Built on Mass Displacement

-

Agriculture2 days ago

Agriculture2 days agoThe Climate Argument Against Livestock Doesn’t Add Up

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day ago‘The electric story is over’