Addictions

Ontario to close 10 safe consumption sites and open 19 recovery hubs

A photo of the South Riverdale neighbourhood. (Photo credit: Andrea Nickel)

News release from Break The Needle

Ontario’s decision to close safe consumption sites near schools and daycares comes in the wake of a bystander’s death and class-action lawsuit

In a dramatic shift in policy, Ontario is closing 10 safe consumption sites located near schools and daycares, citing public safety concerns.

“Our first priority must always be protecting our communities, especially when it comes to our most innocent and vulnerable — our children,” said Ontario Health Minister Sylvia Jones at an Association of Municipalities of Ontario conference in Ottawa on Tuesday.

Safe consumption sites, which enable people to use illicit drugs with sterile equipment under staff supervision, will be prohibited from operating within 200 metres of schools and child-care centres after March 31, 2025.

The province also plans to introduce legislation to prevent municipalities from establishing new consumption sites, requesting the decriminalization of illegal drugs or participating in federal safe supply initiatives, a health ministry press release says.

Safe consumption sites have faced mounting scrutiny in the wake of community feedback highlighting their effect on public safety.

“We’ve noticed a real change from 2021 onwards,” Andrea Nickel, a parent who lives near a safe consumption site at Toronto’s South Riverdale Community Health Centre, told Canadian Affairs in May.

“At the beginning of last year it just escalated out of control.”

Unacceptable danger

Ontario opened its first safe consumption site in 2017 with the aim of reducing overdose deaths and providing users with a gateway to treatment. Today, there are 23 safe consumption sites across the province, 17 of which are provincially funded.

KeepSIX, the safe consumption site in South Riverdale, is among the sites facing closure. Last July, Karolina Huebner-Makurat, a local resident and mother of two, was fatally shot during a gunfight outside the site. Her death prompted Ontario to conduct two reviews of the centre and to also review the 16 other provincially funded sites.

A review of keepSIX conducted by the hospital network Unity Health Toronto and released in February recommended improvements in security, community relations, law enforcement communication and staff training. It did not recommend closure.

The second review, released in April and conducted by former health-care executive Jill Campbell, also opposed closure. It advocated instead for expanded harm reduction and treatment, enhanced security and increased mental health support.

In March 2024, two South Riverdale residents launched a class-action lawsuit against the operator of keepSIX and all levels of government, Canadian Affairs reported in May. The lawsuit alleges the site has exposed the community to unacceptable danger.

The site’s proximity to daycares and schools and its role in exposing children to illicit drugs and used needles are at the heart of that case.

Reacting to this week’s announcement, South Riverdale parent Andrea Nickel said she is supportive of the site’s services. “[But] it is not unreasonable to ask that they are balanced with community safety, specifically kids’ safety.”

South Riverdale’s response cited the centre’s role in reversing 74 overdoses in 2023.

“Every overdose reversed is a life saved,” Anne Marie Aikins, a public affairs consultant at AMA Communications, said on behalf of the centre.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

‘Devil’s in the details’

In Tuesday’s address, Ontario’s health minister also announced a $378-million investment to establish 19 new Homelessness and Addiction Recovery Treatment Hubs (HART hubs) across the province. These recovery-focused hubs will offer social support services and employment assistance to individuals struggling with addiction.

They will not provide supervised drug consumption, needle exchange programs or the “safe supply” of prescribed controlled substances.

“The devil’s in the details with these things,” said John-Paul Michael, an addictions case manager in Toronto who has extensive experience in harm reduction and lived experience with substance use.

“Everyone I know in the harm-reduction community is very much in favour of having better access to treatment, better access to detox, better wraparound care,” he said. “The problem becomes when it is at the expense of other evidence-based care.”

Michael says safe consumption sites are often the only form of health care available to individuals struggling with addiction. Eliminating them would leave these individuals without support, he says.

“Safe consumption sites are essential for saving lives, particularly for those who may never seek formal treatment,” he said. “Eliminating these supports disregards the value of human life.”

Michael is also concerned about the reduction of needle exchange services, which are crucial for managing HIV and Hepatitis C rates and lessening the burden on emergency rooms.

“Community-based nurses at [safe consumption sites] provide basic care that can prevent emergency department visits and potentially severe outcomes, such as [intensive care unit] stays,” Michael said.

The province will soon seek proposals to establish up to 10 HART hubs. Priority will be given to proposals that aim to transition existing safe consumption sites — especially those facing closure — into HART hubs.

“[T]he likelihood is that [these transitions] would happen very quickly,” Health Minister Jones told reporters on Tuesday. “The other applications — it will depend on what they bring forward.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

2025 Federal Election

Poilievre to invest in recovery, cut off federal funding for opioids and defund drug dens

From Conservative Party Communications

Poilievre will Make Recovery a Reality for 50,000 Canadians

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre pledged he will bring the hope that our vulnerable Canadians need by expanding drug recovery programs, creating 50,000 new opportunities for Canadians seeking freedom from addiction. At the same time, he will stop federal funding for opioids, defund federal drug dens, and ensure that any remaining sites do not operate within 500 meters of schools, daycares, playgrounds, parks and seniors’ homes, and comply with strict new oversight rules that focus on pathways to treatment.

More than 50,000 people have lost their lives to fentanyl since 2015—more Canadians than died in the Second World War. Poilievre pledged to open a path to recovery while cracking down on the radical Liberal experiment with free access to illegal drugs that has made the crisis worse and brought disorder to local communities.

Specifically, Poilievre will:

- Fund treatment for 50,000 Canadians. A new Conservative government will fund treatment for 50,000 Canadians in treatment centres with a proven record of success at getting people off drugs. This includes successful models like the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre, which helps people recover and reunite with their families, communities, and culture. To ensure the best outcomes, funding will follow results. Where spaces in good treatment programs exist, we will use them, and where they need to expand, these funds will allow that.

- Ban drug dens from being located within 500 metres of schools, daycares, playgrounds, parks, and seniors’ homes and impose strict new oversight rules. Poilievre also pledged to crack down on the Liberals’ reckless experiments with free access to illegal drugs that allow provinces to operate drug sites with no oversight, while pausing any new federal exemptions until evidence justifies they support recovery. Existing federal sites will be required to operate away from residential communities and places where families and children frequent and will now also have to focus on connecting users with treatment, meet stricter regulatory standards or be shut down. He will also end the exemption for fly-by-night provincially-regulated sites.

“After the Lost Liberal Decade, Canada’s addiction crisis has spiralled out of control,” said Poilievre. “Families have been torn apart while children have to witness open drug use and walk through dangerous encampments to get to school. Canadians deserve better than the endless Liberal cycle of crime, despair, and death.”

Since the Liberals were first elected in 2015, our once-safe communities have become sordid and disordered, while more and more Canadians have been lost to the dangerous drugs the Liberals have flooded into our streets. In British Columbia, where the Liberals decriminalized dangerous drugs like fentanyl and meth, drug overdose deaths increased by 200 percent.

The Liberals also pursued a radical experiment of taxpayer-funded hard drugs, which are often diverted and resold to children and other vulnerable Canadians. The Vancouver Police Department has said that roughly half of all hydromorphone seizures were diverted from this hard drugs program, while the Waterloo Regional Police Service and Niagara Regional Police Service said that hydromorphone seizures had exploded by 1,090% and 1,577%, respectively.

Despite the death and despair that is now common on our streets, bizarrely Mark Carney told a room of Liberal supporters that 50,000 fentanyl deaths in Canada is not “a crisis.” He also hand-picked a Liberal candidate who said the Liberals “would be smart to lean into drug decriminalization” and another who said “legalizing all drugs would be good for Canada.”

Carney’s star candidate Gregor Robertson, an early advocate of decriminalization and so-called safe supply, wanted drug dens imposed on communities without any consultation or public safety considerations. During his disastrous tenure as Vancouver Mayor, overdoses increased by 600%.

Alberta has pioneered an approach that offers real hope by adopting a recovery-focused model of care, leading to a nearly 40 percent reduction in drug-poisoning deaths since 2023—three times the decrease seen in British Columbia. However, we must also end the Liberal drug policies that have worsened the crisis and harmed countless lives and families.

To fund this policy, a Conservative government will stop federal funding for opioids, defund federal drug dens, and sue the opioid manufacturers and consulting companies who created this crisis in the first place.

“Canadians deserve better than the Liberal cycle of crime, despair, and death,” said Poilievre. “We will treat addiction with compassion and accountability—not with more taxpayer-funded poison. We will turn hurt into hope by shutting down drug dens, restoring order in our communities, funding real recovery, and bringing our loved ones home drug-free.”

Addictions

There’s No Such Thing as a “Safer Supply” of Drugs

By Adam Zivo

Sweden, the U.K., and Canada all experimented with providing opioids to addicts. The results were disastrous.

[This article was originally published in City Journal, a public policy magazine and website published by the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. We encourage our readers to subscribe to them for high-quality analysis on urban issues]

Last August, Denver’s city council passed a proclamation endorsing radical “harm reduction” strategies to address the drug crisis. Among these was “safer supply,” the idea that the government should give drug users their drug of choice, for free. Safer supply is a popular idea among drug-reform activists. But other countries have already tested this experiment and seen disastrous results, including more addiction, crime, and overdose deaths. It would be foolish to follow their example.

The safer-supply movement maintains that drug-related overdoses, infections, and deaths are driven by the unpredictability of the black market, where drugs are inconsistently dosed and often adulterated with other toxic substances. With ultra-potent opioids like fentanyl, even minor dosing errors can prove fatal. Drug contaminants, which dealers use to provide a stronger high at a lower cost, can be just as deadly and potentially disfiguring.

Because of this, harm-reduction activists sometimes argue that governments should provide a free supply of unadulterated, “safe” drugs to get users to abandon the dangerous street supply. Or they say that such drugs should be sold in a controlled manner, like alcohol or cannabis—an endorsement of partial or total drug legalization.

But “safe” is a relative term: the drugs championed by these activists include pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl, hydromorphone (an opioid as potent as heroin), and prescription meth. Though less risky than their illicit alternatives, these drugs are still profoundly dangerous.

The theory behind safer supply is not entirely unreasonable, but in every country that has tried it, implementation has led to increased suffering and addiction. In Europe, only Sweden and the U.K. have tested safer supply, both in the 1960s. The Swedish model gave more than 100 addicts nearly unlimited access through their doctors to prescriptions for morphine and amphetamines, with no expectations of supervised consumption. Recipients mostly sold their free drugs on the black market, often through a network of “satellite patients” (addicts who purchased prescribed drugs). This led to an explosion of addiction and public disorder.

Most doctors quickly abandoned the experiment, and it was shut down after just two years and several high-profile overdose deaths, including that of a 17-year-old girl. Media coverage portrayed safer supply as a generational medical scandal and noted that the British, after experiencing similar problems, also abandoned their experiment.

While the U.S. has never formally adopted a safer-supply policy, it experienced something functionally similar during the OxyContin crisis of the 2000s. At the time, access to the powerful opioid was virtually unrestricted in many parts of North America. Addicts turned to pharmacies for an easy fix and often sold or traded their extra pills for a quick buck. Unscrupulous “pill mills” handed out prescriptions like candy, flooding communities with OxyContin and similar narcotics. The result was a devastating opioid epidemic—one that rages to this day, at a cumulative cost of hundreds of thousands of American lives. Canada was similarly affected.

The OxyContin crisis explains why many experienced addiction experts were aghast when Canada greatly expanded access to safer supply in 2020, following a four-year pilot project. They worried that the mistakes of the recent past were being made all over again, and that the recently vanquished pill mills had returned under the cloak of “harm reduction.”

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Most Canadian safer-supply prescribers dispense large quantities of hydromorphone with little to no supervised consumption. Patients can receive up to 40 eight-milligram pills per day—despite the fact that just two or three are enough to cause an overdose in someone without opioid tolerance. Some prescribers also provide supplementary fentanyl, oxycodone, or stimulants.

Unfortunately, many safer-supply patients sell or trade a significant portion of these drugs—primarily hydromorphone—in order to purchase more potent illicit substances, such as street fentanyl.

The problems with safer supply entered Canada’s consciousness in mid-2023, through an investigative report I wrote for the National Post. I interviewed 14 addiction physicians from across the country, who testified that safer-supply diversion is ubiquitous; that the street price of hydromorphone collapsed by up to 95 percent in communities where safer supply is available; that youth are consuming and becoming addicted to diverted safer-supply drugs; and that organized crime traffics these drugs.

Facing pushback, I interviewed former drug users, who estimated that roughly 80 percent of the safer-supply drugs flowing through their social circles was getting diverted. I documented dozens of examples of safer-supply trafficking online, representing tens of thousands of pills. I spoke with youth who had developed addictions from diverted safer supply and adults who had purchased thousands of such pills.

After months of public queries, the police department of London, Ontario—where safer supply was first piloted—revealed last summer that annual hydromorphone seizures rose over 3,000 percent between 2019 and 2023. The department later held a press conference warning that gangs clearly traffic safer supply. The police departments of two nearby midsize cities also saw their post-2019 hydromorphone seizures increase more than 1,000 percent.

The Canadian government quietly dropped its support for safer supply last year, cutting funding for many of its pilot programs. The province of British Columbia (the nexus of the harm-reduction movement) finally pulled back support last month, after a leaked presentation confirmed that safer-supply drugs are getting sold internationally and that the government is investigating 60 pharmacies for paying kickbacks to safer-supply patients. For now, all safer-supply drugs dispensed within the province must be consumed under supervision.

Harm-reduction activists have insisted that no hard evidence exists of widespread diversion of safer-supply drugs, but this is only because they refuse to study the issue. Most “studies” supporting safer supply are produced by ideologically driven activist-scholars, who tend to interview a small number of program enrollees. These activists also reject attempts to track diversion as “stigmatizing.”

The experiences of Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Canada offer a clear warning: safer supply is a reliably harmful policy. The outcomes speak for themselves—rising addiction, diversion, and little evidence of long-term benefit.

As the debate unfolds in the United States, policymakers would do well to learn from these failures. Americans should not be made to endure the consequences of a policy already discredited abroad simply because progressive leaders choose to ignore the record. The question now is whether we will repeat others’ mistakes—or chart a more responsible course.

Our content is always free –

but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

-

Business1 day ago

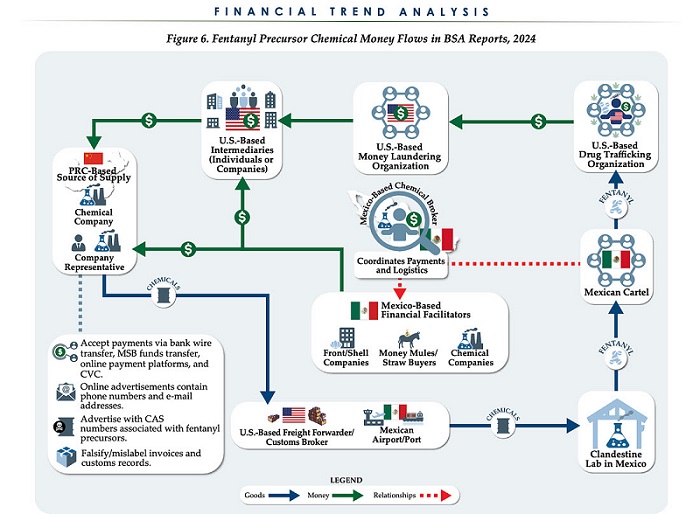

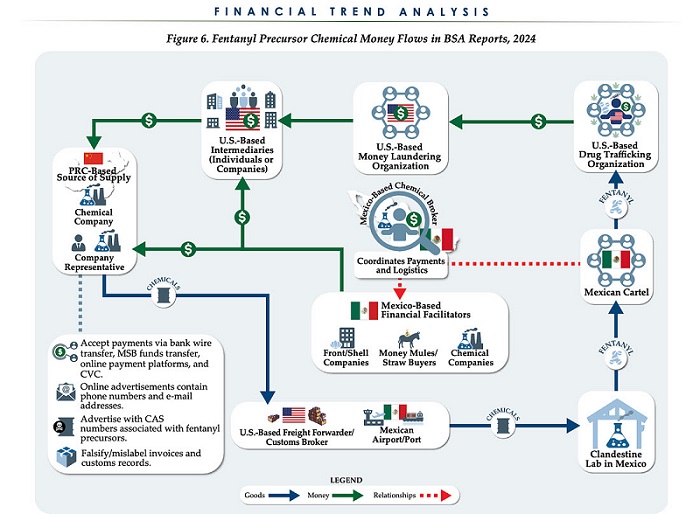

Business1 day agoChina, Mexico, Canada Flagged in $1.4 Billion Fentanyl Trade by U.S. Financial Watchdog

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoTucker Carlson Interviews Maxime Bernier: Trump’s Tariffs, Mass Immigration, and the Oncoming Canadian Revolution

-

espionage1 day ago

espionage1 day agoEx-NYPD Cop Jailed in Beijing’s Transnational Repatriation Plot, Canada Remains Soft Target

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoDOGE Is Ending The ‘Eternal Life’ Of Government

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCanada drops retaliatory tariffs on automakers, pauses other tariffs

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoBREAKING from THE BUREAU: Pro-Beijing Group That Pushed Erin O’Toole’s Exit Warns Chinese Canadians to “Vote Carefully”

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoDOJ Releases Dossier Of Deported Maryland Man’s Alleged MS-13 Gang Ties

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoTrump Executive Orders ensure ‘Beautiful Clean’ Affordable Coal will continue to bolster US energy grid