Business

Ongoing water crisis is a national embarrassment

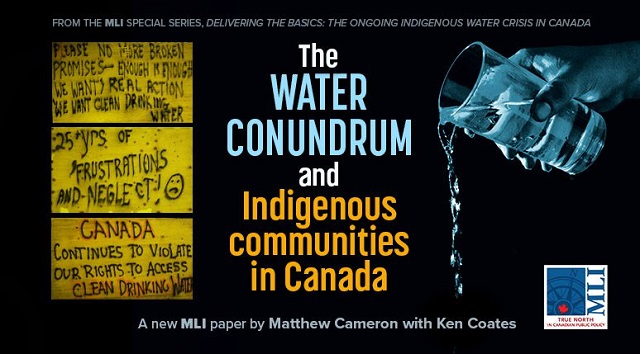

From the MacDonald Laurier Institute

By Matthew Cameron and Ken Coates

Cameron and Coates call for an increased sense of urgency from government and offer several policy initiatives to improve water access for First Nations communities.

Access to clean drinking water is a necessity, yet delivering it to all 40 million Canadians, particularly Indigenous communities, has proven to be elusive. Successive federal governments have both acknowledged the problem, yet have failed to fully eradicate drinking water advisories, which remain in place in at least 27 Indigenous communities.

In a new paper, The water conundrum and Indigenous communities in Canada, Matthew Cameron and Indigenous Program Director Ken Coates shed light on the water insecurity crisis on Canada’s reservations and recommend a number of multijurisdictional policy initiatives, urging policymakers adopt an increased sense of urgency in systematically address the problem – not just throwing money at it.

The authors identify several key barriers to resolving the water insecurity crisis:

- Community location: some communities are located too far away from freshwater reserves; many of these places were settled in the 1950s and 1960s, without scientific study of the suitability of their locations for water purposes;

- Long-term maintenance: trained personnel often work in stressful conditions with little or no local backup, making it difficult to find and retain these workers;

- Little margin for error: nationally determined Canadian water quality standards are, appropriately, difficult to meet, setting a high bar for small, isolated communities;,

- Poor national understanding of the challenges: Canadians who live off reservation are largely unaware of the urgency of the crisis in Indigenous communities.

Cameron and Coates recommend the following policy initiatives to address the crisis:

- Continuous transparency; authorities should make information about water delivery systems and water treatment facility down-times available to the public;

- Region-wide water management systems: these would provide for a sharing of personnel, professional backup, and collective learning about water systems maintenance and treatment facilities, thereby creating a maintenance economy;

- Option of relocation: in extreme cases, where water supplies are unacceptable and alternatives too expensive, communities could be given the option of voluntary relocation and rebuilding in a location with better access to potable water;

- More attention to remote solutions: giving agency to local Indigenous governments and/or companies to resolve the crisis;

- Increasing urgency: Indigenous Canadians wonder if the country cares or even knows about their lack of access to clean water– greater awareness among Canadians can push politicians to seek policy alternatives.

“Understanding the challenges in full, handling emergencies expeditiously, developing and implementing long-term solutions, and committing publicly to providing First Nations with adequate and appropriate water supplies is not an act of generosity or an optional exercise. Maintaining safe drinking water is a foundational responsibility of government,” conclude Cameron and Coates.

“Further delays should not be acceptable.”

To learn more, read the full paper here:

Matthew Cameron is a Yukon-based researcher and academic. He is an Instructor at Yukon University, where he has taught in the Liberal Arts, Indigenous Governance and Multimedia and Communications programs since 2016.

Ken Coates is a Distinguished Fellow and Director of Indigenous Affairs at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and a Professor of Indigenous Governance at Yukon University.

Business

Canadian Police Raid Sophisticated Vancouver Fentanyl Labs, But Insist Millions of Pills Not Destined for U.S.

Sam Cooper

Sam Cooper

Mounties say labs outfitted with high-grade chemistry equipment and a trained chemist reveal transnational crime groups are advancing in technical sophistication and drug production capacity

Amid a growing trade war between Washington and Beijing, Canada—targeted alongside Mexico and China for special tariffs related to Chinese fentanyl supply chains—has dismantled a sophisticated network of fentanyl labs across British Columbia and arrested an academic lab chemist, the RCMP said Thursday.

At a press conference in Vancouver, senior investigators stood behind seized lab equipment and fentanyl supplies, telling reporters the operation had prevented millions of potentially lethal pills from reaching the streets.

“This interdiction has prevented several million potentially lethal doses of fentanyl from being produced and distributed across Canada,” said Cpl. Arash Seyed. But the presence of commercial-grade laboratory equipment at each of the sites—paired with the arrest of a suspect believed to have formal training in chemistry—signals an evolution in the capabilities of organized crime networks, with “progressively enhanced scientific and technical expertise among transnational organized crime groups involved in the production and distribution of illicit drugs,” Seyed added.

This investigation is ongoing, while the seized drugs, precursor chemicals, and other evidence continue to be processed, police said.

Recent Canadian data confirms the country has become an exporter of fentanyl, and experts identify British Columbia as the epicenter of clandestine labs supplied by Chinese precursors and linked to Mexican cartel distributors upstream.

In a statement that appears politically responsive to the evolving Trump trade threats, Assistant Commissioner David Teboul said, “There continues to be no evidence, in this case and others, that these labs are producing fentanyl for exportation into the United States.”

In late March, during coordinated raids across the suburban municipalities of Pitt Meadows, Mission, Aldergrove, Langley, and Richmond, investigators took down three clandestine fentanyl production sites.

The labs were described by the RCMP as “equipped with specialized chemical processing equipment often found in academic and professional research facilities.” Photos released by authorities show stainless steel reaction vessels, industrial filters, and what appear to be commercial-scale tablet presses and drying trays—pointing to mass production capabilities.

The takedown comes as Canada finds itself in the crosshairs of intensifying geopolitical tension.

Fentanyl remains the leading cause of drug-related deaths in Canada, with toxic supply chains increasingly linked to hybrid transnational networks involving Chinese chemical brokers and domestic Canadian producers.

RCMP said the sprawling B.C. lab probe was launched in the summer of 2023, with teams initiating an investigation into the importation of unregulated chemicals and commercial laboratory equipment that could be used for synthesizing illicit drugs including fentanyl, MDMA, and GHB.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

2025 Federal Election

Carney needs to cancel gun ban and buyback

Gage Haubrich

Gage Haubrich

The Canadian Taxpayers Federation is calling on Liberal Leader Mark Carney to stop the gun ban and buyback after he announced he would continue with the scheme.

“Carney needs to scrap this plan and stop wasting taxpayer’s money on it,” said Gage Haubrich, CTF Prairie Director. “Planning to spend potentially billions of dollars on a program that is not going to make Canadians safer is a waste of money.

“Carney needs to be cancelling this wasteful plan, not doubling down on it.”

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre is promising to get rid of Ottawa’s gun bans.

The government said the buyback would cost taxpayers $200 million in 2019. Only buying back the guns could cost up to $756 million, according to the Parliamentary Budget Officer. Government documents show that the buyback is now likely to cost almost $2 billion.

The banned gun list includes more than 2,000 different types of firearms.

Every year since the gun ban was announced in 2020, violent gun crime in Canada has increased.

New Zealand conducted a similar, but more extensive, gun ban and buyback in 2019. New Zealand had 1,216 violent firearm offenses in 2023. That’s 349 more offences than the year before the buyback.

Experts also agree that the buyback won’t make Canadians any safer.

The National Police Federation, the union representing the RCMP, says Ottawa’s buyback “diverts extremely important personnel, resources, and funding away from addressing the more immediate and growing threat of criminal use of illegal firearms.”

“Buyback programs are largely ineffective at reducing gun violence, in large part because the people who participate in such programs are not likely to use those guns to commit violence,” said University of Toronto professor Jooyoung Lee

“Experts say that this gun ban and buyback won’t do anything to make Canadians safer,” Haubrich said. “Carney needs to listen to the experts and commit to cancelling this scheme before it costs taxpayers any more money.”

-

Also Interesting1 day ago

Also Interesting1 day agoMortgage Mayhem: How Rising Interest Rates Are Squeezing Alberta Homeowners

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoConservative Party urges investigation into Carney plan to spend $1 billion on heat pumps

-

Also Interesting2 days ago

Also Interesting2 days agoExploring Wildrobin Technological Advancements in Live Dealer Games

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCommunist China helped boost Mark Carney’s image on social media, election watchdog reports

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoFifty Shades of Mark Carney

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCorporate Media Isn’t Reporting on Foreign Interference—It’s Covering for It

-

Justice2 days ago

Justice2 days agoCanadian government sued for forcing women to share spaces with ‘transgender’ male prisoners

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoStocks soar after Trump suspends tariffs