Business

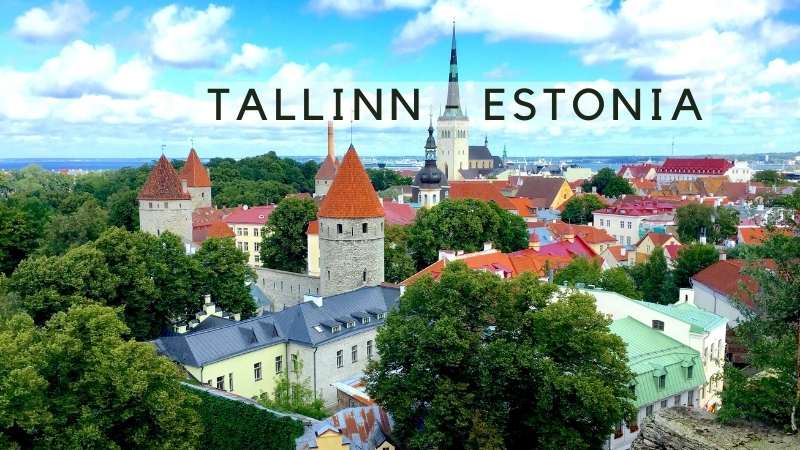

My European Favourites – Tallinn, Estonia

Tallinn is one of those cities that you never hear people talk about visiting, but once you do, it becomes an instant favourite. Whenever we do an itinerary for a hockey, ringette or sightseeing group to Sweden and Finland, I always encourage the group to add a side trip to Estonia’s capital. It is only a two hour ferry ride from Helsinki to Tallinn, so it’s perfect for a day trip.

Tallinn has just under half a million inhabitants and is the largest city of Estonia. It is located directly south of Helsinki on the Gulf of Finland and on the eastern edge of the Baltic Sea. Once known by its German name, Raval, Tallinn has one of the best preserved old towns in Europe. Unlike many towns in Europe, Tallinn’s historic old town was never destroyed by war and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. I like to think of it as a smaller Prague. The city started building protective walls in the 13th century, and over time, it enlarged to a defence system of over two kilometers with gates and towers. Much of these structures survive today including twenty of the pointy red roofed towers. In some areas, it is possible to walk along the walls.

Near the old town you will find traditional neighborhoods with colorful wooden houses, green spaces and the redeveloped bustling port area. Estonians are blessed with public beaches to enjoy in the summer months and nearby forests to explore on nature walks. Within view of the old town, there is a modern city, complete with skyscrapers and all the modern amenities you would expect. How modern is Tallinn? It has free public WIFI, and as a high-tech city, it has become a leader in the sector of cyber security. You may have used the services of a well-known Estonian startup company named Skype.

About Estonia

There is evidence that the area was settled as far back as 5,000 years ago, but the city became an important trading hub in the 14th to 16th centuries when it was a member of the Hanseatic League, which controlled trade in the Baltic and North Seas. Even at that time, the city only had about 8,000 inhabitants.

Over the years, Estonia has been ruled by the Holy Roman Empire, Denmark, Sweden and Russia. The country gained short lived independence from Russia after WWI only to be reclaimed as part of the Soviet Union after WWII. Like most of the countries that became part of the USSR, they suffered through a fifty year period of communist policies and stagnation. In 1991, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Estonia regained its independence. Since then it has flourished into a western style city while maintaining its rich cultural and architectural history. It is a member of the European Union and NATO.

Tallinn’s distinctive mix of a modern and historic skyline as we arrive on the ferry from Helsinki.

Ferry to Tallinn

Tallinn is a two-hour ferry ride south from Helsinki, and it’s possible to go early in the morning across the Gulf of Finland and return late on the evening ferry. The Tallink ferry has sitting areas on different decks plus shopping and dining options onboard. If possible, I would recommend an overnight stay near the old town and return to Helsinki the following evening.

From Sweden, you can arrive on the overnight ferry that leaves Stockholm in the early evening and arrives in Tallinn in the morning. Your individual ticket includes a cabin that can sleep up to four people with two single beds and two pull down upper berths. Onboard, you can enjoy shopping, entertainment, bars and restaurants. Another option from Stockholm is to take the ferry to Riga and spend a couple of days in Latvia’s capital. The drive from Riga to Tallin is about four hours, and I usually like to stop along the way in the seaside resort city of Parnu to have lunch and walk in the city centre.

A Tale of Two Towns

Tallinn’s historic center is separated into two areas, Toompea, and Vanalinn. At one time, they were two feuding medieval towns. The upper town, Toompea, includes the aptly named Toompea Castle. The lower town, Vanalinn, has narrow alleyways, the town square, shops and restaurants. Vanalinn, was the Hanseatic League trading center filled with merchants from Germany, Denmark and Sweden. The two areas are connected by two passages called the short leg (Lühike Jalg) and the long leg (Pikk jalg).

Toompea, Tallinn’s Upper Town

As expected, the Toompea Castle sits high above the lower town on an ancient stronghold site that dates back to a wooden fortress in the 9th century. The castle, a symbol of political power through the ages, has been expanded and remodeled over the years by Estonia’s rulers to meet their needs.

Once a castle of ancient Estonians starting in the 11th century, it was later used by the Danish during most of the 13th century. It wasn’t until the 14th and 15th centuries, while in the hands of the Holy Roman Empire’s Teutonic Order, that it was built to resemble what we see today. The religious order changed the castle interior to include a chapel, chapel house, convent and dormitories for the knights. They added defence towers named Pikk Hermann (Tall Hermann), Landskrone (Crown of the land), Pilsticker (Arrow Sharpener) and Stür den Kerl (Ward Off Enemy) to protect each of its four corners. During the 16th century when Estonia became a part of Sweden, they changed the castle from a crusader’s fortress to a symbol of political power, with an administrative and ceremonial purpose.

Tall Hermann, entrance to the Governors Garden and the Toompea Castle’s pink palace.

When the Russians took over in the 18th century, the Czar had the castle turned into a palace by adding a Baroque and Neoclassical wing to the eastern part of the castle and a public park on the south east. When Estonia declared its first independence from Russia after WWI, the former convent of the Teutonic Order was transferred into an assembly hall for the Parliament of Estonia, named the Riigikogu. After being disbanded during the Soviet era from 1940 to 1991, the assembly, the Riigikogu, was reinstated in 1992 as the Estonian Parliament with 101 members.

I like to start my tour of Tallinn in the upper town just outside of the Toompea Castle, so I can get a good look at the impressive Tall Herman and original castle wall from the Governors Garden. During the castle’s evolution, the Stür den Kerl castle tower has been demolished while the others have been integrated into building projects. The 48 meter high Tall Hermann still stands and has become an important symbol of Tallinn and the nation. The Estonian flag is raised atop the tower every day at sunrise as the national anthem plays and it is lowered at sunset.

Around the corner from the park is the Lossi Plats (Castle Square) where we can see the pink palace which was added to the front of Toompea Castle during the renovations by Russian Czars. Topped by the Estonian flag, the one-time medieval fortress is now clearly the modern centre of government for Estonia. On the opposite side of the square is a richly decorated Russian orthodox cathedral.

The Castle Square, the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral and an Russian Orthodox mosaic.

Alexander Nevsky Cathedral

The striking Alexander Nevsky Cathedral was built in 1900 in Russian Revival style when Estonia was part of the Russian Empire. It is Tallinn’s largest orthodox cupola cathedral and is dedicated to Saint Alexander Nevsky, a Russian military hero, who in 1242, won a famous “Battle of the Ice” against the Teutonic Knights on Lake Peipus. The lake on Estonia’s eastern border is shared with Russia with the modern day border between the countries being about half way across.

During the USSR period, the church came into decline due to communist non-religious policies. Since 1991, the church has been meticulously restored even though it is a constant reminder of Russia’s influence, power and oppression over Estonia through the ages. There were actually plans to demolish the structure in 1924, but it was spared due to a lack of funds to raze such a large building. Today, the church is one of Tallinn’s most visited attractions and is unique due to its contrasting architectural style.

The church exterior has five onion domes, each topped with a gilded Orthodox cross. The church has eleven bells that were cast in St. Petersburg, including one massive 16 ton bell.

Like other traditional Orthodox churches, there are no pews as worshippers were required to stand during services. The ornate interior has three alters, stained glass windows and three gilded wooden iconostases (wall of icons and religious paintings) which separate the nave from the alters. Entrance to the cathedral is free. The intricate detail and colors of the mosaics and icons are amazing and well worth seeing.

St. Mary’s Church, the top of the baroque tower spire with the year 1772.

Leaving the Castle Square, we venture further into the upper town, and about 100 meters in, we reach the Kiriku Plats (Church Square) and a white medieval church with a baroque bell tower. The Toomkrik built by the Danes in the 13th century, also known as the Dome Chrurch or St. Mary’s Cathedral, is Estonia’s oldest church. Originally a Roman Catholic cathedral, it became Lutheran in the mid 16th century and is the seat of Tallinn’s Archbishop of the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church. Although the church endured severe damage in the great fire of 1684, it was the only building on Toompea left standing. It was restored to its previous state shortly after the fire and a new baroque spire was added in the 18th century.

From the Church Square, we can see the light green colored Estonian Knighthood House. This is the 4th Knighthood house that was built for noble Knights to meet and enjoy festivities. The Knighthood was formed in 1584 by the Baltic German nobles, but it was disbanded in 1920. Currently, the building is used by the Estonian Academy of Arts. On the right of the building we take the Kohtu street until we reach the end and turn right onto a small open area between two buildings.

Kohtuotsa views: Towards the harbour and of the old town with skyscrapers in the distance.

A Panoramic View and Sweet Almonds

As we enter the Kohtuotsa viewing platform, which is a courtyard between two buildings, the smell of candied almonds overwhelms the senses. A wooden kiosk with a couple of girls dressed in traditional costume are making batches of sweet almonds in a copper pot. They have a sample for you to try, and when you do, the sale is complete. They have two options, Magus Mandel (Candied) or Soolane Mandel (Salty). I have the candied ones every time.

There is a stone wall at the end of the platform with amazing panoramic views of Tallinn. Looking to the left, you can see the white tower of St. Olaf’s Church amongst medieval towers with the harbour and the sea in the distance. Directly ahead are the roof tops and spires of the lower town with the skycrapers of the city in the distance. It’s quite a contrast of architecture from medieval structures to modern steel and glass.

Another nearby viewing platform is the Patkuli, which is reached by climbing 157 steps from the old town up to Toompea. This platform offers a great view of the harbour area.

Leaving the Kohtuotsa, we go back towards the Nevsky Cathedral and take the Long Leg Street down into the lower town. We walk along the fortification walls until we reach the Long Leg Tower and enter the lower town.

Walking down the Long Leg passage to the Long Leg Tower and into the lower town.

Vanalinn – Tallinn’s Lower Town

Emerging from the Long Leg Tower, we continue on Pikk street until we reach the Grand Guild Square (Suurgildi Plats). The square is named after the medieval gold colored Great Guild Hall that is now the Estonian History Museum. The Great Guild was a medieval association of merchants, artisans, and craftsmen in Tallinn from the 14th century until 1920. On the square, we also find the Lutheran Holy Spirit Church (Pühavaimu kirik). The white washed medieval church has stained glass gothic windows, an octagonal bell tower and an interesting 17th century carved clock on the façade. If you enter the church, you will see elaborate wood working, especially on the alter.

The Maiasmokk Café, the Holy Spirit Church, the church clock and the pharmacy sign.

Established in 1864, the Maiasmokk Café on the square, is the oldest in Tallinn. The café interior hasn’t changed for over a century. It is famous for its marzipan, which is said to have been originated in Tallinn. Marzipan is made from almond meal and either sugar or honey. The café’s Marzipan Room details the city’s history of making marzipan including traditional marzipan figures made from special molds.

If we take a small passage along the church, we will reach the Town Hall Square (Raekoja Plats). As we enter the square, two doors down on our left is the Town Hall Pharmacy (Revali Raeapteek). This pharmacy dates back to 1422, and it may be the world’s oldest pharmacy in continuous use.The pharmacy has a museum where you can see some of the old time medicines and potions. You can test various herbal tea blends picked from local fields in the basement of the Town Hall Pharmacy (or Raeapteek) or explore the exposition of the 17th to the 20th-century medicine in the back room. You can purchase some of the products from the middle ages including teas, spices, chocolate, marzipan and claret, a potent libation made from wine and spices that dates back to 1467.

The Old Town Square’s colorful buildings, the Town Hall and a Town Hall dragon water spout.

The lively Town Hall Square, one of the best preserved medieval town squares in the world, was a market place in the Middle ages. Many of the colorful buildings on the square were once medieval merchants’ homes, offices and warehouses from the Hanseatic Golden Age. During the summer months, the restaurants around the square set up their umbrellaed patios where you can enjoy lunch and a cool beverage as you watch locals and tourists mill about. Restaurants like “III Draakon” and ‘Olde Hansa” offer a unique medieval experience with menu items made with elk, bear and boar meat.

The square is the centre of the Old Town Days medieval festival, concerts, fairs and the centuries old Christmas market. It is said that in 1441, the Brotherhood of the Blackbeards, a professional association of merchants, ship owners and foreigners, erected the very first Christmas tree here on the square. Today, in addition to the tree, the Christmas market fills the square with kiosks selling everything from gingerbread to knitted mittens and handicrafts. Other kiosks sell snacks, oysters and mulled wine to keep you warm. Kids can drop off letters at the Santa Claus cabin and ride the carousels in a magical setting. On a stage, hundreds of performers take turns entertaining the crowds during the markets month long stay from the 27th of November to the 27th of December.

Sweet Almond vendor and Old Town buildings. The Christmas market stage and a kiosk.

The town hall, built in 1404, sits prominently on the square and is the oldest in the Baltic and Scandinavian regions. It is no longer in the seat of the municipal government but is used for special events and ceremonies, and is the home of the Tallinn City Musuem. The town hall tower can be climbed in the summer months to get another great view of Tallinn. Since 1530, a weather vane of Vana Toomas, or Old Thomas, has been keeping lookout atop the spire. Old Thomas, who is holding a sword and an arrow, is said to be a protector of Tallinn.

The square is spectacular, but it can be touristy. I like to wander through the cobblestone streets and alleyways surrounding the centre to find restaurants and cafes where the locals frequent. Walking these side streets is like taking a time machine back to the medieval ages, but you will find interesting little museums, galleries and shops selling local products like amber.

St. Catherine’s Passage kiosks and alley. The Viru Gate tower and the white Viru Hotel.

St. Catherine’s Passage, the Viru Gate and the KGB

From the Old Town square if we go to the right of the old town and down the busy pedestrian Viru Street we will reach the St. Catherine’s passage on Müürivahe Street. The passage leads to the St. Catherine’s Monastery which was founded in 1246 by the Monks of the Dominican Order. The monastery is the oldest building in Tallinn. At the monastery, you can visit the chapel, gallery, or book a private tour. The medieval passage itself, formerly known as Monk’s alley, has the tall fortification wall on one side with little kiosks below selling handicrafts and 15th to 17th century residences on the other side, with some now being used as artists workshops.

Only steps away from the St. Catherine’s passage is the 14th century Viru Gate that was part of Tallinn’s wall defences. When the entrances to the Old Town were widened in the late 1800’s, many of the gates were destroyed. The Viru Gate’s corner towers survived and are a great divide from the medieval town on one side and the modern city on the other.

During the 50 year Soviet occupation of Estonia, the KGB had its headquarters in the old town at Pagari 1. In its basement, suspected enemies of the state were imprisoned, interrogated and tortured. If convicted of crimes, they were either shot or sent to labour camps in Siberia. The tall white Viru Hotel that can be seen clearly in the distance from the Viru Gate has a KGB Museum. Like any hotel where foreigners stayed, the hotel had to have spying facilities for the KGB. The museum tells the story of their activities and the Soviet mindset.

St. Olaf’s Church, the Fat Margaret Tower, and the Kadriorg Palace.

St. Olaf’s Church

On the northern edge of the old town is Tallinn’s biggest medieval building, the iconic St Olaf’s Church. Named after the sainted Norwegian king Olav II Haraldsson, the church was the tallest building in the world from between 1549 and 1625 due to its 124 meter tower. The church had three great fires in 1625, 1820 and in 1931 caused by lightning striking its tall spire. In fact, lightning has struck the church at least 10 times. During the Soviet occupation, the spire was used as a radio tower and KGB surveillance point. Today, if you climb 232 steps on a winding staircase you will have a great view of the city and the harbour area. I’m not sure I would go on an overcast day tough.

Near the church is the Fat Margaret tower which houses a part of the Maritime Museum. The main part of the museum is the Seaplane Harbour (Lennusadam) which is located a couple of kilometers away. It is one of Europe’s biggest maritime museums with a submarine, icebreaker, seaplane, an aquarium, simulators and other activities.

Other Things to do in Tallinn

If you go to the wall connecting the Nunna, Sauna and Kuldjala towers, you can walk the city walls, like the medieval guards that protected the town.

Near the old town, the Rotermann quarter has been transformed from old warehouses and factory buildings into a trendy and lively neighborhood with modern architecture.

Kumu Art Museum, with a modern architectural design, depicts various periods of Estonian art from the Academic Style to Modernism, from Soviet Pop Art to contemporary art.

Near the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, Tallinn’s Museum of Occupations tells the history of the country’s occupation by the Nazis during WWII and then the Soviets.

Patarei Prison is a huge complex in the Kalamaja district that can be visited in the summer months. Once an artillery battery in the 19th century, it became a prison from 1919 to 2002.

The 314 meter high Tallinn TV Tower has a glass-floored viewing platform on the 21st floor with a 360 degree view of the city. Thrill seekers can take a safety harnessed walk on the open deck.

Foodies may want to visit the Kalev Chocolate factory or the Baltic Station Market.

Just Outside of Tallinn

Just outside Tallinn is Kadriorg Park. Established by Peter the Great in 1718, it has the Kadriorg Palace as well as beautiful gardens and woods. The park includes a concert area, children’s park, a people’s park and a Japanese garden.

The 72 hectare Estonian Open-Air Museum has around 80 reconstructed buildings from the 18th to 20th centuries. The traditional structures were brought here from throughout Estonia.

Tallinn is not overly priced, or especially crowded with tourists. You can easily spend a few days in Tallinn, and it is well worth adding to any itinerary of Sweden or Finland. You will thank me for it.

Explore Europe With Us

Azorcan Global Sport, School and Sightseeing Tours have taken thousands to Europe on their custom group tours since 1994. Visit azorcan.net to see all our custom tour possibilities for your group of 26 or more. Individuals can join our “open” signature sport, sightseeing and sport fan tours including our popular Canada hockey fan tours to the World Juniors. At azorcan.net/media you can read our newsletters and listen to our podcasts.

Images compliments of Paul Almeida and Azorcan Tours.

Click here to read more stories from the series My European Favourites.

Bjorn Lomborg

Net zero’s cost-benefit ratio is CRAZY high

From the Fraser Institute

The best academic estimates show that over the century, policies to achieve net zero would cost every person on Earth the equivalent of more than CAD $4,000 every year. Of course, most people in poor countries cannot afford anywhere near this. If the cost falls solely on the rich world, the price-tag adds up to almost $30,000 (CAD) per person, per year, over the century.

Canada has made a legal commitment to achieve “net zero” carbon emissions by 2050. Back in 2015, then-Prime Minister Trudeau promised that climate action will “create jobs and economic growth” and the federal government insists it will create a “strong economy.” The truth is that the net zero policy generates vast costs and very little benefit—and Canada would be better off changing direction.

Achieving net zero carbon emissions is far more daunting than politicians have ever admitted. Canada is nowhere near on track. Annual Canadian CO₂ emissions have increased 20 per cent since 1990. In the time that Trudeau was prime minister, fossil fuel energy supply actually increased over 11 per cent. Similarly, the share of fossil fuels in Canada’s total energy supply (not just electricity) increased from 75 per cent in 2015 to 77 per cent in 2023.

Over the same period, the switch from coal to gas, and a tiny 0.4 percentage point increase in the energy from solar and wind, has reduced annual CO₂ emissions by less than three per cent. On that trend, getting to zero won’t take 25 years as the Liberal government promised, but more than 160 years. One study shows that the government’s current plan which won’t even reach net-zero will cost Canada a quarter of a million jobs, seven per cent lower GDP and wages on average $8,000 lower.

Globally, achieving net-zero will be even harder. Remember, Canada makes up about 1.5 per cent of global CO₂ emissions, and while Canada is already rich with plenty of energy, the world’s poor want much more energy.

In order to achieve global net-zero by 2050, by 2030 we would already need to achieve the equivalent of removing the combined emissions of China and the United States — every year. This is in the realm of science fiction.

The painful Covid lockdowns of 2020 only reduced global emissions by about six per cent. To achieve net zero, the UN points out that we would need to have doubled those reductions in 2021, tripled them in 2022, quadrupled them in 2023, and so on. This year they would need to be sextupled, and by 2030 increased 11-fold. So far, the world hasn’t even managed to start reducing global carbon emissions, which last year hit a new record.

Data from both the International Energy Agency and the US Energy Information Administration give added cause for skepticism. Both organizations foresee the world getting more energy from renewables: an increase from today’s 16 per cent to between one-quarter to one-third of all primary energy by 2050. But that is far from a transition. On an optimistically linear trend, this means we’re a century or two away from achieving 100 percent renewables.

Politicians like to blithely suggest the shift away from fossil fuels isn’t unprecedented, because in the past we transitioned from wood to coal, from coal to oil, and from oil to gas. The truth is, humanity hasn’t made a real energy transition even once. Coal didn’t replace wood but mostly added to global energy, just like oil and gas have added further additional energy. As in the past, solar and wind are now mostly adding to our global energy output, rather than replacing fossil fuels.

Indeed, it’s worth remembering that even after two centuries, humanity’s transition away from wood is not over. More than two billion mostly poor people still depend on wood for cooking and heating, and it still provides about 5 per cent of global energy.

Like Canada, the world remains fossil fuel-based, as it delivers more than four-fifths of energy. Over the last half century, our dependence has declined only slightly from 87 per cent to 82 per cent, but in absolute terms we have increased our fossil fuel use by more than 150 per cent. On the trajectory since 1971, we will reach zero fossil fuel use some nine centuries from now, and even the fastest period of recent decline from 2014 would see us taking over three centuries.

Global warming will create more problems than benefits, so achieving net-zero would see real benefits. Over the century, the average person would experience benefits worth $700 (CAD) each year.

But net zero policies will be much more expensive. The best academic estimates show that over the century, policies to achieve net zero would cost every person on Earth the equivalent of more than CAD $4,000 every year. Of course, most people in poor countries cannot afford anywhere near this. If the cost falls solely on the rich world, the price-tag adds up to almost $30,000 (CAD) per person, per year, over the century.

Every year over the 21st century, costs would vastly outweigh benefits, and global costs would exceed benefits by over CAD 32 trillion each year.

We would see much higher transport costs, higher electricity costs, higher heating and cooling costs and — as businesses would also have to pay for all this — drastic increases in the price of food and all other necessities. Just one example: net-zero targets would likely increase gas costs some two-to-four times even by 2030, costing consumers up to $US52.6 trillion. All that makes it a policy that just doesn’t make sense—for Canada and for the world.

Business

‘Great Reset’ champion Klaus Schwab resigns from WEF

From LifeSiteNews

Schwab’s World Economic Forum became a globalist hub for population control, radical climate agenda, and transhuman ideology under his decades-long leadership.

Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum and the face of the NGO’s elitist annual get-together in Davos, Switzerland, has resigned as chair of WEF.

Over the decades, but especially over the past several years, the WEF’s Davos annual symposium has become a lightning rod for conservative criticism due to the agendas being pushed there by the elites. As the Associated Press noted:

Widely regarded as a cheerleader for globalization, the WEF’s Davos gathering has in recent years drawn criticism from opponents on both left and right as an elitist talking shop detached from lives of ordinary people.

While WEF itself had no formal power, the annual Davos meeting brought together many of the world’s wealthiest and most influential figures, contributing to Schwab’s personal worth and influence.

Schwab’s resignation on April 20 was announced by the Geneva-based WEF on April 21, but did not indicate why the 88-year-old was resigning. “Following my recent announcement, and as I enter my 88th year, I have decided to step down from the position of Chair and as a member of the Board of Trustees, with immediate effect,” Schwab said in a brief statement. He gave no indication of what he plans to do next.

Schwab founded the World Economic Forum – originally the European Management Forum – in 1971, and its initial mission was to assist European business leaders in competing with American business and to learn from U.S. models and innovation. However, the mission soon expanded to the development of a global economic agenda.

Schwab detailed his own agenda in several books, including The Fourth Industrial Revolution (2016), in which he described the rise of a new industrial era in which technologies such artificial intelligence, gene editing, and advanced robotics would blur the lines between the digital, physical, and biological worlds. Schwab wrote:

We stand on the brink of a technological revolution that will fundamentally alter the way we live, work, and relate to one another. In its scale, scope, and complexity, the transformation will be unlike anything humankind has experienced before. We do not yet know just how it will unfold, but one thing is clear: the response to it must be integrated and comprehensive, involving all stakeholders of the global polity, from the public and private sectors to academia and civil society …

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, finally, will change not only what we do but also who we are. It will affect our identity and all the issues associated with it: our sense of privacy, our notions of ownership, our consumption patterns, the time we devote to work and leisure, and how we develop our careers, cultivate our skills, meet people, and nurture relationships. It is already changing our health and leading to a “quantified” self, and sooner than we think it may lead to human augmentation.

How? Microchips implanted into humans, for one. Schwab was a tech optimist who appeared to heartily welcome transhumanism; in a 2016 interview with France 24 discussing his book, he stated:

And then you have the microchip, which will be implanted, probably within the next ten years, first to open your car, your home, or to do your passport, your payments, and then it will be in your body to monitor your health.

In 2020, mere months into the pandemic, Schwab published COVID-19: The Great Reset, in which he detailed his view of the opportunity presented by the growing global crisis. According to Schwab, the crisis was an opportunity for a global reset that included “stakeholder capitalism,” in which corporations could integrate social and environmental goals into their operations, especially working toward “net-zero emissions” and a massive transition to green energy, and “harnessing” the Fourth Industrial Revolution, including artificial intelligence and automation.

Much of Schwab’s personal wealth came from running the World Economic Forum; as chairman, he earned an annual salary of 1 million Swiss francs (approximately $1 million USD), and the WEF was supported financially through membership fees from over 1,000 companies worldwide as well as significant contributions from organizations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Vice Chairman Peter Brabeck-Letmathe is now serving as interim chairman until his replacement has been selected.

-

2025 Federal Election18 hours ago

2025 Federal Election18 hours agoOttawa Confirms China interfering with 2025 federal election: Beijing Seeks to Block Joe Tay’s Election

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoIndigenous-led Projects Hold Key To Canada’s Energy Future

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoMany Canadians—and many Albertans—live in energy poverty

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada Urgently Needs A Watchdog For Government Waste

-

2025 Federal Election17 hours ago

2025 Federal Election17 hours agoHow Canada’s Mainstream Media Lost the Public Trust

-

2025 Federal Election7 hours ago

2025 Federal Election7 hours agoBREAKING: THE FEDERAL BRIEF THAT SHOULD SINK CARNEY

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoPope Francis has died aged 88

-

2025 Federal Election17 hours ago

2025 Federal Election17 hours agoReal Homes vs. Modular Shoeboxes: The Housing Battle Between Poilievre and Carney