Censorship Industrial Complex

“Minority Report”: The Sequel. A warning to the Canadian Church

From the Frontier Centre for Pubic Policy

In the 2002 futuristic movie, “Minority Report,” viewers are introduced to a ground-breaking technology that allows law enforcement to preview a crime before it is committed. Then this determination becomes the basis for the arrest and the sentencing of the “pre-crime” perpetrator.

In a case of life imitating art, on February 26, the Canadian government tabled legislation containing provisions that are eerily like the plot imagined in Tom Cruise’s blockbuster.

The proposed legislation should be of great concern to churches and pastors who may face unprecedented legal exposure if it is passed.

Bill C-63, the Online Harms Act, seeks to “promote online safety.” The Act endeavours, in part, to protect children from online sexual exploitation and requires the mandatory reporting of online child pornography by internet providers. So far, so good.

But the proverbial devil is lurking in the details of the provisions pertaining to online hate speech, which are simply breathtaking.

The Act represents what many consider to be the most dangerous assault on free speech this country has ever seen, prompting Canadian novelist, Margaret Atwood, to refer to the proposed legislation as “Orwellian.”

This bill would not only have a glacial effect on free speech, but it would also trigger an open season on religious organizations that do not align with mainstream dogma.

Here are some of the reasons behind this apocalyptic assessment of this piece of legislation.

The bill defines hate speech as speech that “is likely to foment detestation or vilification of an individual or group of individuals on the basis of a prohibited ground of discrimination.”

This definition is so vague, ambiguous, and far reaching that it could apply to any opinion that diverges from the government-sanctioned media narrative.

The responsibility of judging complaints would be lodged with the Human Rights Commission. This fact alone is deeply worrisome, as the threshold for deciding guilt is much lower in the Human Rights Tribunal than in a criminal court, where a person must be found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

Plaintiffs could file their complaints anonymously without incurring any legal costs. Defendants, on the other hand, would be bound to retain legal counsel at considerable expense to them.

Should they win their case, the plaintiffs stand to be awarded up to $20,000. The defendants could be imposed an additional fine of up to $50,000. Should a legal violation be considered to have been motivated by hate, the defendants could also face life imprisonment!

The incontrovertible proof that Bill C-63 is not about protecting children but strangling free speech resides in what is now ironically referred to as the “Minority Report” provision.

As unhinged as it sounds, the legislation states that if a member of the public has grounds to believe that someone is likely to engage in hateful speech, that person can appeal to a provincial judge who may then subject the defendant to house arrest and other restrictions.

Human nature being what it is, there is no telling the number of people who will be incentivized to file complaints knowing they have much to gain and nothing to lose.

Conservative churches would become instant targets in the tsunami of human rights violation initiatives that the proposed legislation would trigger.

In response, churches may decide to play it safe by restricting their services to in-person participation or by self-censuring.

While either choice would no doubt be welcome by a government that wants to silence those who hold “unacceptable views,” to quote Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, such restrictions would no doubt prove to be detrimental to the churches and the common good.

The proposed legislation is not about protecting children. It’s about unleashing the mob against those who would oppose an agenda that is already proving to be an existential threat to liberal society.

Bill C-63 is currently at the nexus of the fight to preserve our most fundamental freedoms, Canadian democracy, and the well-being of future generations.

Churches have a window of opportunity to voice their opposition to this appalling piece of legislation.

What can be done?

First, be informed. Videos posted by the Canadian Constitution Foundation are a great place to start.

Second, promote congregational awareness. Church leaders can no longer pretend that such issues are beyond the scope of their pulpit. To denounce injustice is indeed part and parcel of the church’s prophetic mandate.

Third, church members should contact their member of parliament to express their opposition to Bill C-63.

Canadian churches have historically chosen to remain on the far edges of the culture war currently raging in the Western world. But if Bill C-63 receives royal assent, these same churches may soon unwittingly find themselves in the middle of the very battlefield they so vigorously sought to avoid.

Pierre Gilbert is Associate Professor Emeritus at Canadian Mennonite University.

Business

‘Great Reset’ champion Klaus Schwab resigns from WEF

From LifeSiteNews

Schwab’s World Economic Forum became a globalist hub for population control, radical climate agenda, and transhuman ideology under his decades-long leadership.

Klaus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum and the face of the NGO’s elitist annual get-together in Davos, Switzerland, has resigned as chair of WEF.

Over the decades, but especially over the past several years, the WEF’s Davos annual symposium has become a lightning rod for conservative criticism due to the agendas being pushed there by the elites. As the Associated Press noted:

Widely regarded as a cheerleader for globalization, the WEF’s Davos gathering has in recent years drawn criticism from opponents on both left and right as an elitist talking shop detached from lives of ordinary people.

While WEF itself had no formal power, the annual Davos meeting brought together many of the world’s wealthiest and most influential figures, contributing to Schwab’s personal worth and influence.

Schwab’s resignation on April 20 was announced by the Geneva-based WEF on April 21, but did not indicate why the 88-year-old was resigning. “Following my recent announcement, and as I enter my 88th year, I have decided to step down from the position of Chair and as a member of the Board of Trustees, with immediate effect,” Schwab said in a brief statement. He gave no indication of what he plans to do next.

Schwab founded the World Economic Forum – originally the European Management Forum – in 1971, and its initial mission was to assist European business leaders in competing with American business and to learn from U.S. models and innovation. However, the mission soon expanded to the development of a global economic agenda.

Schwab detailed his own agenda in several books, including The Fourth Industrial Revolution (2016), in which he described the rise of a new industrial era in which technologies such artificial intelligence, gene editing, and advanced robotics would blur the lines between the digital, physical, and biological worlds. Schwab wrote:

We stand on the brink of a technological revolution that will fundamentally alter the way we live, work, and relate to one another. In its scale, scope, and complexity, the transformation will be unlike anything humankind has experienced before. We do not yet know just how it will unfold, but one thing is clear: the response to it must be integrated and comprehensive, involving all stakeholders of the global polity, from the public and private sectors to academia and civil society …

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, finally, will change not only what we do but also who we are. It will affect our identity and all the issues associated with it: our sense of privacy, our notions of ownership, our consumption patterns, the time we devote to work and leisure, and how we develop our careers, cultivate our skills, meet people, and nurture relationships. It is already changing our health and leading to a “quantified” self, and sooner than we think it may lead to human augmentation.

How? Microchips implanted into humans, for one. Schwab was a tech optimist who appeared to heartily welcome transhumanism; in a 2016 interview with France 24 discussing his book, he stated:

And then you have the microchip, which will be implanted, probably within the next ten years, first to open your car, your home, or to do your passport, your payments, and then it will be in your body to monitor your health.

In 2020, mere months into the pandemic, Schwab published COVID-19: The Great Reset, in which he detailed his view of the opportunity presented by the growing global crisis. According to Schwab, the crisis was an opportunity for a global reset that included “stakeholder capitalism,” in which corporations could integrate social and environmental goals into their operations, especially working toward “net-zero emissions” and a massive transition to green energy, and “harnessing” the Fourth Industrial Revolution, including artificial intelligence and automation.

Much of Schwab’s personal wealth came from running the World Economic Forum; as chairman, he earned an annual salary of 1 million Swiss francs (approximately $1 million USD), and the WEF was supported financially through membership fees from over 1,000 companies worldwide as well as significant contributions from organizations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Vice Chairman Peter Brabeck-Letmathe is now serving as interim chairman until his replacement has been selected.

Business

Ted Cruz, Jim Jordan Ramp Up Pressure On Google Parent Company To Deal With ‘Censorship’

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

By Andi Shae Napier

Republican Texas Sen. Ted Cruz and Republican Ohio Rep. Jim Jordan are turning their attention to Google over concerns that the tech giant is censoring users and infringing on Americans’ free speech rights.

Google’s parent company Alphabet, which also owns YouTube, appears to be the GOP’s next Big Tech target. Lawmakers seem to be turning their attention to Alphabet after Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta ended its controversial fact-checking program in favor of a Community Notes system similar to the one used by Elon Musk’s X.

Cruz recently informed reporters of his and fellow senators’ plans to protect free speech.

Dear Readers:

As a nonprofit, we are dependent on the generosity of our readers.

Please consider making a small donation of any amount here. Thank you!

“Stopping online censorship is a major priority for the Commerce Committee,” Cruz said, as reported by Politico. “And we are going to utilize every point of leverage we have to protect free speech online.”

Following his meeting with Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai last month, Cruz told the outlet, “Big Tech censorship was the single most important topic.”

Jordan, Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, sent subpoenas to Alphabet and other tech giants such as Rumble, TikTok and Apple in February regarding “compliance with foreign censorship laws, regulations, judicial orders, or other government-initiated efforts” with the intent to discover how foreign governments, or the Biden administration, have limited Americans’ access to free speech.

“Throughout the previous Congress, the Committee expressed concern over YouTube’s censorship of conservatives and political speech,” Jordan wrote in a letter to Pichai in March. “To develop effective legislation, such as the possible enactment of new statutory limits on the executive branch’s ability to work with Big Tech to restrict the circulation of content and deplatform users, the Committee must first understand how and to what extent the executive branch coerced and colluded with companies and other intermediaries to censor speech.”

Jordan subpoenaed tech CEOs in 2023 as well, including Satya Nadella of Microsoft, Tim Cook of Apple and Pichai, among others.

Despite the recent action against the tech giant, the battle stretches back to President Donald Trump’s first administration. Cruz began his investigation of Google in 2019 when he questioned Karan Bhatia, the company’s Vice President for Government Affairs & Public Policy at the time, in a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing. Cruz brought forth a presentation suggesting tech companies, including Google, were straying from free speech and leaning towards censorship.

Even during Congress’ recess, pressure on Google continues to mount as a federal court ruled Thursday that Google’s ad-tech unit violates U.S. antitrust laws and creates an illegal monopoly. This marks the second antitrust ruling against the tech giant as a different court ruled in 2024 that Google abused its dominance of the online search market.

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoOttawa Confirms China interfering with 2025 federal election: Beijing Seeks to Block Joe Tay’s Election

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoIndigenous-led Projects Hold Key To Canada’s Energy Future

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoMany Canadians—and many Albertans—live in energy poverty

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoHow Canada’s Mainstream Media Lost the Public Trust

-

2025 Federal Election17 hours ago

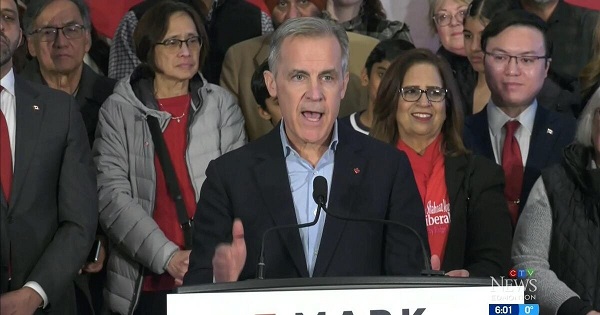

2025 Federal Election17 hours agoBREAKING: THE FEDERAL BRIEF THAT SHOULD SINK CARNEY

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada Urgently Needs A Watchdog For Government Waste

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

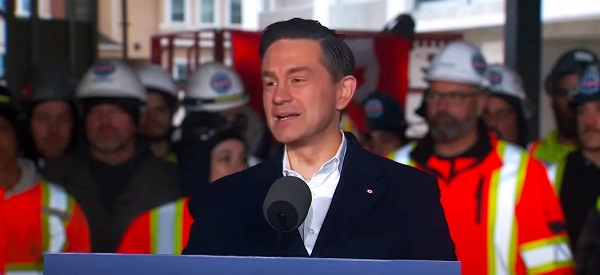

2025 Federal Election1 day agoReal Homes vs. Modular Shoeboxes: The Housing Battle Between Poilievre and Carney

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoPope Francis has died aged 88