Opinion

In 2021 Collicutt Centre, Red Deer’s 4th and last recreational centre will be 20 years old.

2021 will be a pivotal year in Red Deer.

Collicutt Centre will be celebrating it’s 20 anniversary just as the shovels hit the dirt on a new Multi-plex Aquatic Centre.

2001 the Collicutt opened it’s doors for the first time. Red Deer’s population was a hefty 68,308 residents.

1991 Mayor McGhee and council decided it was prudent for Red Deer to have a fourth recreational complex. The population was 58,252 residents and a recreational centre for every 15,000 was the established goal.

2001 Red Deer’s fourth recreational centre opened to a population ratio of a recreational centre for every 17,077 residents. Already behind the target.

There was as recently as last year that the ratio of 1 indoor ice rink per 15,000 was established as determined for recreational complexes. With that in mind we should have built one in 2004 when the population was at 75,923. Giving us 5 recreation centres or 1 for every 15,000 residents as was deemed appropriate. Then again in 2010 when our population was 90,084 we should have built the 6th recreational complex.

If we followed this reasoning we should be planning on opening our 7th recreational complex because our population is 99,832 according to our last municipal census and if we were to grow at 1,2% annually we should hit 105,000 in 2021.

That did not and will not happen. The best we can hope for is a new Aquatic Centre to open in 2022.

The ideal goal is one for every 15,000 residents but if we build a 5th recreational complex with an indoor pool then we would have to settle for 1 for every 21,000 residents.

A fifth recreational complex north of hwy 11a would service the residents, expand tourism and kick start development north of 11a.

The current thinking is the city will tear down the downtown recreation centre and build the aquatic centre there. Leaving us with only 4 or 1 recreational complex for every 26,125 residents.

Instead of 7 we would be left with 4 for another 20 years.

What do we do? Councillor Tanya Handley has declared that she cannot support building the aquatic centre downtown with poor parking but would support building it as Councillor Frank Wong has been advocating, north of 11a near Hazlett Lake to kick start development. Newcomer Councillor Michael Dawe would consider moving the aquatic centre as would another.

That gives us 4 councillors but with 8 councillors and the mayor voting on the issue in a year, we need the commitment of 5 to ensure a new pool and not just a replacement.

I am asking all councillors and the mayor to commit to building a new aquatic centre north of 11a. Why now?

The city is a bureaucracy that tends to move slowly and in precise steps. It is always too early then it’s too late. We need commitment now so the city can make the necessary adjustments when necessary. Please commit.

Opinion

Canadians Must Turn Out in Historic Numbers—Following Taiwan’s Example to Defeat PRC Election Interference

Beijing deploys organized crime to sway Taiwan’s elections — and likely uses similar tactics in Canada, Taiwanese official warns

As Canadians head to the polls on Monday, The Bureau is reposting this report, originally filed from Taiwan, in the public interest.

The 2025 federal election has already been confirmed—through official Canadian intelligence disclosures and our reporting—to have been injured by aggressive foreign interference operations emanating from Beijing. These operations include highly coordinated cyberattacks against Conservative candidate Joe Tay, as well as the potential of in-person intimidation during canvassing efforts in Greater Toronto, according to The Bureau’s source awareness.

The scale and impact of Beijing’s interference in Canada’s 2025 election remains under investigation and is not yet fully understood. However, The Bureau believes it is critical to underscore that as voters face disinformation, manipulation, and suppression attempts, and certain candidates evidently receive support from Xi Jinping’s United Front, the best response is robust democratic participation.

Our groundbreaking 2023 report from Taiwan demonstrates that even under greater and more sustained foreign assault—including sophisticated polling manipulation, corrupt media influence, and the use of organized crime to distort public opinion—Taiwanese citizens have consistently defended their democracy by turning out to vote in record numbers.

Buttressing The Bureau’s findings, the Brookings Institution confirmed: “Taiwanese saw the results of this in 2024: China’s interference became more dangerous as it evolved to be more subtle and untraceable. The Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda campaign in Taiwan may have undergone a paradigm shift, as it evolved from a centralized and top-down approach to a more decentralized one.” This United Front work included tactics in which “individuals or groups in Taiwan may receive Chinese funding for election campaigns or to produce fake election polls.”

The Bureau encourages all Canadians, regardless of political preference or predictions from polls and odds-makers, to exercise their democratic right to vote. As Taiwan’s example shows, a free society depends not only on recognizing threats, but on the collective will of its citizens to confront them—at the ballot box.

TAIPEI, Taiwan — Beijing has interfered in Taiwan’s elections by using organized crime networks to influence votes for certain candidates and is likely using the same methods in Canada, a senior Taiwanese official said Tuesday.

Responding to questions from journalists in Taiwan, Jyh-horng Jan, deputy minister of the Mainland Affairs Council, said that Beijing uses “collaborators” including illegal gambling bosses and Taiwanese businessmen to interfere in Taiwan’s elections.

The Bureau asked Jan if he could describe Taiwanese knowledge of Beijing’s election interference methods, in comparison to examples of China’s recent interference in Canadian federal elections through the Chinese Communist Party’s United Front, which has allegedly clandestinely funded Beijing’s favoured candidates, according to Canadian intelligence investigations.

“We’ve been facing China’s United Front for over half a century in Taiwan and I think China’s tactics have been changing all the time,” Jan said. “Since we are in the lead up to a presidential election next January, we know that they have already started the United Front campaign against us.”

The Council is the Taiwanese government arm mandated to deal with all matters related to Beijing, and works with intelligence and police agencies in order to assess and counteract the Chinese Communist Party’s subversion campaigns.

Jan said the Council has already gathered intelligence indicating China is running influence campaigns against certain candidates in Taiwan’s upcoming January 2024 presidential election.

The front-runner in that contest, Taiwanese vice-president William Lai, is viewed by Beijing as a “separatist” and strong opponent of the Chinese Communist Party’s plans to pressure Taiwan into subordination.

Without naming Lai or any other candidates as Beijing’s alleged targets, Jan said the Council has learned wealthy businessmen will be used as fronts for Beijing to criticize candidates the Chinese Communist Party disfavours.

“We recently found out that China don’t like some of our current presidential candidates. So they’re going to use our business associations who are investing in China to make public statements against certain candidates,” Jan said. “By doing this, they want to shape this image that Taiwanese people are expressing opposition to a certain candidate. Whereas it is actually their voice.”

Jan also told a gathering of international journalists of an alleged method of Chinese election interference that focuses on underground gambling networks.

He described a complex scheme in which Beijing funded and used organized crime gambling rings to influence votes for certain candidates in Taiwan.

“I will share an example that has been happening in Taiwan and probably elsewhere, including Canada,” Jan said. “This is a very classic tactic of China’s election interference.”

According to Jan, the scheme involves underground betting on election candidates, and how the gambling odds can influence actual results at the ballot boxes.

“In the lead up to elections there will always be illegal election operations in Taiwan, so China tends to take advantage of such operations and they will work with the operators from these election gambling rings,” Jan said.

“Beijing will work with such election gambling operators telling them if you can get more people to wager on this specific candidate they will get a very high cash pay off,” Jan said. “And when the operators spread the word [in the betting community] the voters will flock to support this specific candidate.”

Chinese agents also inject funds into these underground betting operations that influence voting results, Jan said.

The Bureau asked Jan to clarify, whether he was alleging that Beijing is systematically using organized crime to influence votes for certain candidates.

“Because this is illegal activity, of course our law enforcement will crack down on such activity and the police were also [able to] issue a fine in this regard,” Jan said. “So this information, regarding illegal election; this is something that is out there, so I can afford confirm that.”

In response to a follow-up question from The Bureau, regarding a ProPublica investigative report that alleged Beijing used Fujian transnational crime suspects in its secret police stations, in Italy, Jan confirmed that his Council recognizes Beijing’s use of transnational crime networks for various objectives.

“So the criminal organization that you were talking about; this criminal organization exists wherever there are overseas Chinese, and one of their responsibilities is to control the activity of overseas Chinese,” Jan said.

(The Bureau reported from Taiwan with international media at the invitation of and with support from Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which has no input on The Bureau’s coverage.)

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

C2C Journal

“Freedom of Expression Should Win Every Time”: In Conversation with Freedom Convoy Trial Lawyer Lawrence Greenspon

Lawrence Greenspon Defends the Fundamental Freedoms of All Canadians

By Lynne Cohen

“Law is an imperfect profession,” famed American lawyer Alan Dershowitz – defender of such notorious clients as Claus Von Bülow, Jeffrey Epstein, Harvey Weinstein and O.J. Simpson – once wrote. “There is no perfect justice…But there is perfect injustice, and we know it when we see it.”

Like Dershowitz, Lawrence Greenspon has spent a career fighting injustice in all its forms. Over the past 45 years Greenspon has become one of Canada’s best-known criminal lawyers through his defence of a long list of clients at risk of being crushed by Canada’s legal system – from terrorists to political pariahs to, most recently, Tamara Lich, the petite grandmother who became the public face of the 2022 Freedom Convoy protest.

In taking on these cases, Greenspon is not only giving his clients the best defence possible, he’s also defending the very legitimacy of Canada’s legal system.

Lich faced six charges and up to 10 years in jail for her role organizing the peaceful Ottawa protest. Earlier this month she was found guilty on a single charge of mischief. The Crown says it intends to seek a two-year sentence for that one charge.

In an interview, Greenspon said he decides on cases based on whether he believes in the cause central to the case: “What’s at stake. And can I make a difference?” What attracted him to Lich’s case were key aspects of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms that Greenspon felt needed defending. “Canadians have a constitutionally protected right to freedom of expression and freedom of peaceful assembly,” he said. “These are fundamental freedoms, and they’re supposed to be protected for all of us.”

At issue was the impact the protest had on some downtown Ottawa residents and whether that conflicted with Lich’s right to free speech and peaceful protest. “We were prepared to admit right off the bat that there were individuals who lived in downtown Ottawa who experienced some interference with their enjoyment of their property,” Greenspon noted.

“But when you put freedom of expression and freedom of peaceful assembly on a scale against interference with somebody’s enjoyment of property, there’s no contest. Freedom of association and peaceful assembly, and freedom of expression – these should win every time.”

Such a spirited defence of Canadians’ Charter rights is characteristic of the entire body of Greenspon’s legal work. Although his clients aren’t always as endearing as Lich.

Prior to being in the spotlight for the Lich trial, most Canadians probably remember Greenspon from the 2008 trial of Mohamed Momin Khawaja, the first person charged under Canada’s Anti-Terrorism Act. The evidence against Khawaja was substantial and convincing. He was even planning a suicide mission against Israel. Greenspon is a Jew. It was not an issue.

“The fundamental point is that everybody’s entitled to a defence,” Greenspon said. What really mattered was the constitutionality of the new terror law, which Greenspon argued impinged on the free speech rights of Canadians.

In 2018 Greenspon represented Joshua Boyle, who faced over a dozen criminal charges stemming from accusations made by his wife Caitlin Coleman after they returned from being held captive in Afghanistan. Greenspon’s meticulous cross-examination of Coleman led Judge Peter Doody of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice to conclude, “I do not believe her, just as I do not believe Mr. Boyle.” All charges against Boyle were dismissed.

He also defended Senator Mike Duffy, who in 2014 found himself charged in connection with an expense account scandal. “Duffy’s presumption of innocence had been completely annihilated. I had no problem representing Mike. In fact, I feel proud to have represented Mike,” he said.

Throughout his legal career, Greenspon has fought tirelessly for the constitutional rights of all his clients, regardless of public sympathy or apparent guilt. While such a stance can make him unpopular, such work offers a crucial bulwark against the state’s misuse of its authority in pursuing particular individuals, as well as the gradual erosion of the liberties promised to all Canadians by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Every Canadian has a stake in ensuring the court system is held to account at all times, regardless of the apparent evidence, current political mood or public support.

Without the work of lawyers such as Greenspon, Charter rights can soon deteriorate into empty platitudes – as the federal government’s shocking treatment of the peaceful Freedom Convoy protesters revealed. That included the unjustified imposition of the Emergencies Act, the freezing of donors’ bank accounts, the mass arrest of supporters and the marked reluctance to grant bail to those charged.

As Greenspon pointed out numerous times during the trial, the conciliatory and always respectful Lich represents the very ideals of peaceful protest in Canada. And for the sole charge on which she was convicted, she still faces two years in a federal penitentiary.

In the case of Khawaja, Greenspon was asked by an Ottawa synagogue to explain why he, as a Jew, was defending an Islamist terrorist. “I told the synagogue members, somebody has to stand up for the person who finds themselves set against the entire machinery of the state. In this case it happens to be Khawaja. But what if the next guy is named Dreyfus?”

Lynne Cohen is a writer at C2C Journal, where the longer original version of this story first appeared.

-

2025 Federal Election10 hours ago

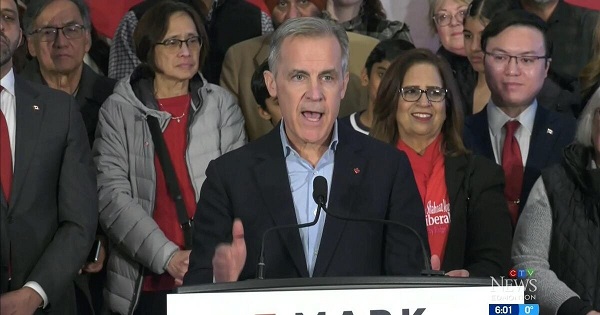

2025 Federal Election10 hours agoThe Federal Brief That Should Sink Carney

-

2025 Federal Election12 hours ago

2025 Federal Election12 hours agoHow Canada’s Mainstream Media Lost the Public Trust

-

2025 Federal Election15 hours ago

2025 Federal Election15 hours agoOttawa Confirms China interfering with 2025 federal election: Beijing Seeks to Block Joe Tay’s Election

-

2025 Federal Election14 hours ago

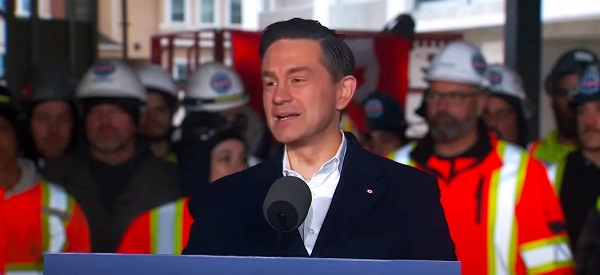

2025 Federal Election14 hours agoReal Homes vs. Modular Shoeboxes: The Housing Battle Between Poilievre and Carney

-

John Stossel11 hours ago

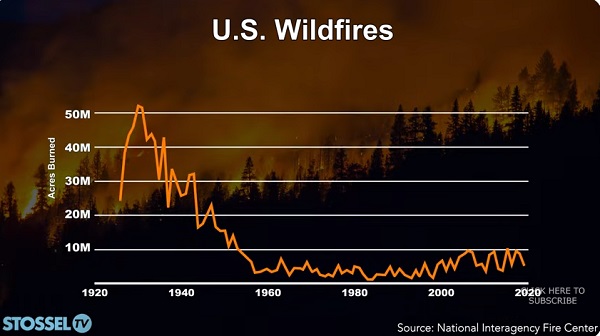

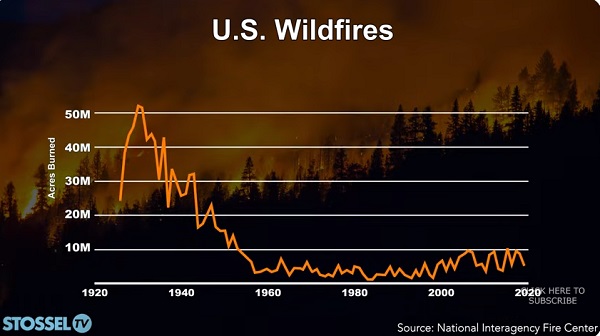

John Stossel11 hours agoClimate Change Myths Part 2: Wildfires, Drought, Rising Sea Level, and Coral Reefs

-

COVID-1913 hours ago

COVID-1913 hours agoNearly Half of “COVID-19 Deaths” Were Not Due to COVID-19 – Scientific Reports Journal

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoPoilievre Campaigning To Build A Canadian Economic Fortress

-

Entertainment2 days ago

Entertainment2 days agoPedro Pascal launches attack on J.K. Rowling over biological sex views