Bjorn Lomborg

How the climate elite spread misery

Submitted by Bjorn Lomborg of the Copenhagen Consensus Center

|

The chattering classes who jet to conferences at Davos or Aspen have for years been telling the rest of us that our biggest immediate threats are climate change, environmental disasters and biodiversity loss. Yet, their singular focus on climate change ignores that people are much more worried about rampant inflation, especially rising food and energy prices.

Unfortunately, climate policies are making those problems worse. Lomborg writes in The Wall Street Journal that when people are cold, hungry and broke, they rebel. If the elites continue pushing incredibly expensive policies that are disconnected from the urgent challenges facing most people, we need to brace for chaos.

He also discussed this topic in interviews with Paul Gigot on The Journal Editorial Report, with Laura Ingrahamand with Stuart Varney.

The rich are denying the poor the power to develop

Rich countries – despite their climate rhetoric – are heavily relying on coal, oil and gas to cope with the current energy crisis. Yet, the G7 recently decided to stop funding any fossil fuel projects in the developing world, immorally blocking the path for poorer countries to develop. This is clearly not what developing countries want, as their leaders and ordinary citizens have made very clear.

Cost-benefit analysis can help policymakers maximize social returns

The Copenhagen Consensus approach has successfully introduced a rational, data-driven input to national priority-setting in many countries, including Bangladesh, Haiti, India, Ghana and Malawi in recent years.

With the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals reaching their halfway mark by the end of this year, it is time to assess how much progress countries have made towards the goals, and what they should focus on over the following eight years to create the largest-possible benefits for their societies.

Lomborg argues in a full page article for the leading Honduran newspaper El Heraldo that data from economic science can help politicians and their officials pick more of the really effective programs and slightly fewer of the less so, to maximize social returns for every dollar spent.

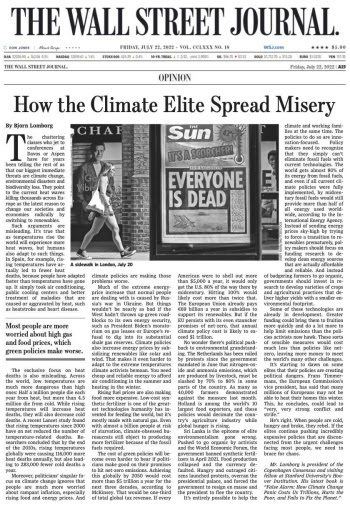

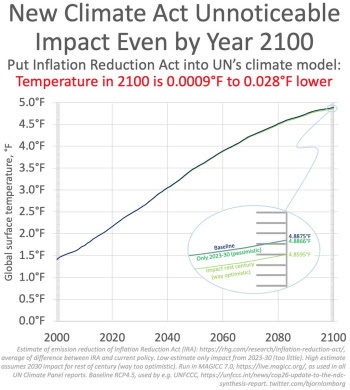

US $369 billion climate bill has virtually no impact

President Biden enthusiastically describes his administration’s new Inflation Reduction Act as “the most significant legislation in history to tackle the climate crisis.” Curiously though, neither officials nor media praising the IRA are stating the actual climate impact of spending $369 billion on the bill’s climate provisions.

There’s a good reason for this: As Lomborg explains on social media and TV interviews, e.g. with Varney and Kudlow, the UN’s own climate model shows that the impact will be impossible to detect by mid-century and still unnoticeable even in the best case by the year 2100.

Lomborg’s findings were also highlighted in a Wall Street Journal editorial and by Fox News which reported that the White House and leading proponents of the bill “didn’t respond to inquiries” pointing out that the bill would slow down rising temperatures by merely 0.0009°F to 0.028°F in 2100.

Green energy needs to be affordable for everyone

The climate-policy approach of trying to push consumers and businesses away from fossil fuels with price spikes is causing substantial pain with little climate pay-off. In rich countries, this approach risks growing resentment and strife, as France saw with the “yellow vest” protest movement.

But for the poorest billions, rising energy prices are even more serious because they block the pathway out of poverty and make fertilizer unaffordable for farmers, imperiling food production. The well-off in rich countries might be able to withstand the pain of some climate policies, but emerging economies like India or low-income countries in Africa cannot afford to sacrifice poverty eradication and economic development to tackle climate change.

Read Bjorn Lomborg’s globally-syndicated column in publications such as New York Post and Press of Atlantic City (both USA), Financial Post (Canada), Neue Zürcher Zeitung (Switzerland), O Globo (Brazil), The Australian, Berlingske (Denmark), de Telegraaf (Netherlands), Tempi(Italy), Listy z naszego sadu (Poland), Addis Fortune(Ethiopia), Milenio (Mexico), El Periodico (Guatemala), La Prensa (Nicaragua), La Tercera (Chile), El Pais(Uruguay), La Prensa Grafica (El Salvador), El Universal(Venezuela), CRHoy (Costa Rica) and Listy z naszego sadu(Poland).

Lomborg also discussed the importance of affordable and reliable energy on Tucker Carlson Tonight.

‘False Alarm’ around the world

Bjorn Lomborg’s bestselling book False Alarm* is now available in more than a dozen languages. Here is the Chinese edition, other translations include German, Czech, Spanish, Finnish, Norwegian and many more.

Bjorn Lomborg’s bestselling book False Alarm* is now available in more than a dozen languages. Here is the Chinese edition, other translations include German, Czech, Spanish, Finnish, Norwegian and many more.

The book remains an international success. The English original has been reprinted eight times in hardcover and six times in paperback, and several translations are also being reprinted now.

*As an Amazon Associate Copenhagen Consensus earns fromqualifying purchases.

Bjorn Lomborg

Net zero’s cost-benefit ratio is CRAZY high

From the Fraser Institute

The best academic estimates show that over the century, policies to achieve net zero would cost every person on Earth the equivalent of more than CAD $4,000 every year. Of course, most people in poor countries cannot afford anywhere near this. If the cost falls solely on the rich world, the price-tag adds up to almost $30,000 (CAD) per person, per year, over the century.

Canada has made a legal commitment to achieve “net zero” carbon emissions by 2050. Back in 2015, then-Prime Minister Trudeau promised that climate action will “create jobs and economic growth” and the federal government insists it will create a “strong economy.” The truth is that the net zero policy generates vast costs and very little benefit—and Canada would be better off changing direction.

Achieving net zero carbon emissions is far more daunting than politicians have ever admitted. Canada is nowhere near on track. Annual Canadian CO₂ emissions have increased 20 per cent since 1990. In the time that Trudeau was prime minister, fossil fuel energy supply actually increased over 11 per cent. Similarly, the share of fossil fuels in Canada’s total energy supply (not just electricity) increased from 75 per cent in 2015 to 77 per cent in 2023.

Over the same period, the switch from coal to gas, and a tiny 0.4 percentage point increase in the energy from solar and wind, has reduced annual CO₂ emissions by less than three per cent. On that trend, getting to zero won’t take 25 years as the Liberal government promised, but more than 160 years. One study shows that the government’s current plan which won’t even reach net-zero will cost Canada a quarter of a million jobs, seven per cent lower GDP and wages on average $8,000 lower.

Globally, achieving net-zero will be even harder. Remember, Canada makes up about 1.5 per cent of global CO₂ emissions, and while Canada is already rich with plenty of energy, the world’s poor want much more energy.

In order to achieve global net-zero by 2050, by 2030 we would already need to achieve the equivalent of removing the combined emissions of China and the United States — every year. This is in the realm of science fiction.

The painful Covid lockdowns of 2020 only reduced global emissions by about six per cent. To achieve net zero, the UN points out that we would need to have doubled those reductions in 2021, tripled them in 2022, quadrupled them in 2023, and so on. This year they would need to be sextupled, and by 2030 increased 11-fold. So far, the world hasn’t even managed to start reducing global carbon emissions, which last year hit a new record.

Data from both the International Energy Agency and the US Energy Information Administration give added cause for skepticism. Both organizations foresee the world getting more energy from renewables: an increase from today’s 16 per cent to between one-quarter to one-third of all primary energy by 2050. But that is far from a transition. On an optimistically linear trend, this means we’re a century or two away from achieving 100 percent renewables.

Politicians like to blithely suggest the shift away from fossil fuels isn’t unprecedented, because in the past we transitioned from wood to coal, from coal to oil, and from oil to gas. The truth is, humanity hasn’t made a real energy transition even once. Coal didn’t replace wood but mostly added to global energy, just like oil and gas have added further additional energy. As in the past, solar and wind are now mostly adding to our global energy output, rather than replacing fossil fuels.

Indeed, it’s worth remembering that even after two centuries, humanity’s transition away from wood is not over. More than two billion mostly poor people still depend on wood for cooking and heating, and it still provides about 5 per cent of global energy.

Like Canada, the world remains fossil fuel-based, as it delivers more than four-fifths of energy. Over the last half century, our dependence has declined only slightly from 87 per cent to 82 per cent, but in absolute terms we have increased our fossil fuel use by more than 150 per cent. On the trajectory since 1971, we will reach zero fossil fuel use some nine centuries from now, and even the fastest period of recent decline from 2014 would see us taking over three centuries.

Global warming will create more problems than benefits, so achieving net-zero would see real benefits. Over the century, the average person would experience benefits worth $700 (CAD) each year.

But net zero policies will be much more expensive. The best academic estimates show that over the century, policies to achieve net zero would cost every person on Earth the equivalent of more than CAD $4,000 every year. Of course, most people in poor countries cannot afford anywhere near this. If the cost falls solely on the rich world, the price-tag adds up to almost $30,000 (CAD) per person, per year, over the century.

Every year over the 21st century, costs would vastly outweigh benefits, and global costs would exceed benefits by over CAD 32 trillion each year.

We would see much higher transport costs, higher electricity costs, higher heating and cooling costs and — as businesses would also have to pay for all this — drastic increases in the price of food and all other necessities. Just one example: net-zero targets would likely increase gas costs some two-to-four times even by 2030, costing consumers up to $US52.6 trillion. All that makes it a policy that just doesn’t make sense—for Canada and for the world.

Bjorn Lomborg

Global Warming Policies Hurt the Poor

From the Fraser Institute

Had prices been kept at the same level, an average family of four would be spending £1,882 on electricity. Instead, that family now pays £5,425 per year. The average UK person now consumes just over 10 kWh per day—a low point in consumption not seen since the 1960s.

We are often told by climate campaigners that climate change is especially pernicious because its effects over coming decades will disproportionately affect the poorest people in Canada and the world. Unfortunately, they miss that climate policies are directly hurting the poor right now.

More energy leads to better, healthier, longer lives. Less energy means fewer opportunities. Climate policies demand we pay more for less reliable energy. The impact is greater if you’re poorer: the wealthy might grumble about higher costs but can generally absorb them; the poor are forced to cut back.

For evidence, look to the United Kingdom which has led the world on stiff climate policies and net zero promises for some two decades, sustained by successive governments: its inflation-adjusted electricity price, weighted across households and industry, has tripled from 2003 to 2023, mostly because of climate policies. The total, annual UK electricity bill is now $CAD160 billion, which is $CAD105 billion more than if prices in real terms had stayed unchanged since 2003. This unnecessary increase is so costly that it is twice the entire cost that the UK spends on elementary education. Had prices been kept at the same level, an average family of four would be spending £1,882 on electricity. Instead, that family now pays £5,425 per year.

Over that time, the richest one per cent absorbed the costs and even managed to increase their consumption. But the poorest fifth of UK households saw their electricity consumption decline by a massive one-third.

The effects of climate policies mean the UK can afford less power. The average UK person now consumes just over 10 kWh per day—a low point in consumption not seen since the 1960s. While global individual electricity consumption is steadily increasing, the energy available to an average Brit is sharply decreasing.

Climate policies hurt the poor even in energy-abundant countries like Canada and the United States. Universally, poor people in well-off countries use much more of their limited budgets paying for electricity and heating. US low-income consumers spend three-times more on electricity as a percentage of their total spending than high-income consumers. It’s easy to understand why the elites have no problem supporting electricity or gas price hikes—they can easily afford them.

As mentioned in the article on cold and heat deaths, high energy prices literally kill people—and this is especially true for the poor. Cold homes are one of the leading causes of deaths in winter through strokes, heart attacks, and respiratory diseases. Researchers looked at the natural experiment that happened in the United States around 2010, when fracking delivered a dramatic reduction in costs of natural gas. The massive increase in availability of natural gas drove down the price of heating. The scientists concluded that every single winter, lower energy prices from fracking save about 12,500 Americans from dying. To put this another way, all else being equal, a reversal and hike in energy prices would kill an additional 12,500 people each year.

As bleak as things are for the poor in rich countries, virtue-signaling climate policy has even farther-reaching impacts on the developing world, where people desperately need more access to the cheap and plentiful energy that previously allowed rich nations to develop. In the poor half of the world, more than two billion people have to cook and keep warm with polluting fuels such as dung and wood. This means their indoor air is so polluted it is equivalent to smoking two packs of cigarettes a day—causing millions of deaths each year.

In Africa, electricity is so scarce that the total electricity available per person is much less than what a single refrigerator in the rich world uses. This hampers industrialization, growth, and opportunity. Case in point: The rich world on average has 650 tractors per 50km2, while the impoverished parts of Africa have just one.

But rich countries like Canada—through restrictions on bilateral aid and contributions to global bodies like the World Bank—refuse to fund anything remotely fossil fuel-related. More and more development and aid money is being diverted to climate change, away from the world’s more pressing challenges.

Canada still gets more than three-quarters of its energy (not just electricity) from fossil fuels. Yet, it blocks poor countries from achieving more energy access, with the naïve suggestion that the poor “skip” to intermittent solar and wind with an unreliability that the rich world does not accept to fulfil its own, much bigger needs.

A large 2021 survey of leaders in low- and middle-income countries shows education, employment, peace and health are at the top of their development priorities, with climate coming 12th out of 16 issues. But wealthy countries refuse to pay attention to what poor countries need, in the name of climate change.

The blinkered pursuit of climate goals blinds politicians in rich countries like Canada to the impacts on the poor, both here and across the world in developing nations. Climate policies that cause higher energy costs and push people toward unreliable energy sources disproportionately burden those least able to bear them.

-

2025 Federal Election16 hours ago

2025 Federal Election16 hours agoOttawa Confirms China interfering with 2025 federal election: Beijing Seeks to Block Joe Tay’s Election

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoIndigenous-led Projects Hold Key To Canada’s Energy Future

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoMany Canadians—and many Albertans—live in energy poverty

-

2025 Federal Election16 hours ago

2025 Federal Election16 hours agoHow Canada’s Mainstream Media Lost the Public Trust

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada Urgently Needs A Watchdog For Government Waste

-

2025 Federal Election5 hours ago

2025 Federal Election5 hours agoBREAKING: THE FEDERAL BRIEF THAT SHOULD SINK CARNEY

-

2025 Federal Election16 hours ago

2025 Federal Election16 hours agoReal Homes vs. Modular Shoeboxes: The Housing Battle Between Poilievre and Carney

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoPope Francis has died aged 88