Energy

Halfway Between Kyoto and 2050: Zero Carbon Is a Highly Unlikely Outcome

From the Fraser Institute

By Vaclav Smil

The global goal to achieve “net-zero” carbon emissions by 2050 is impractical and unrealistic, finds a new study published today by the Fraser Institute, an independent, non-partisan Canadian public policy think-tank.

“The plan to eliminate fossil fuels and achieve a net-zero economy faces formidable economic, political and practical challenges,” said Vaclav Smil, professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba and author of Halfway Between Kyoto and 2050: Zero Carbon Is a Highly Unlikely Outcome.

Canada is now also committed to this goal. In 2021, the federal government passed legislation mandating that the country will achieve “net-zero” emissions—that is, will either emit no greenhouse gas emissions or offset its emissions through other activities (e.g. tree planting)—by 2050.

Yet, despite international agreements and significant spending and regulations by governments worldwide, global dependence on fossil fuels has steadily increased over the past three decades. By 2023, global fossil fuel consumption was 55 per cent higher than in 1997 (when the Kyoto Protocol was adopted). And the share of fossil fuels in global energy consumption has only slightly decreased, dropping from 86 per cent in 1997 to 82 per cent in 2022 (the latest year of complete production data).

Widespread adoption of electric vehicles—also a key component of Ottawa’s net-zero plan—by 2040 will require more than 40 times more lithium and up to 25 times more cobalt, nickel and graphite worldwide (compared to 2020 levels). There are serious questions about the ability to achieve such increases in mineral and metal production.

Although the eventual cost of global decarbonization cannot be reliably quantified, achieving zero carbon by 2050 would require spending substantially higher than for any previous long-term peacetime commitments. Moreover, high-income countries (including Canada) are also expected to finance new energy infrastructure in low-income economies, further raising their decarbonization burdens.

Finally, achieving net-zero requires extensive and sustained global cooperation among countries—including China and India—that have varied levels of commitment to decarbonization.

“Policymakers must face reality—while ending our reliance on fossil fuels may be a desirable long-term goal, it cannot be accomplished quickly or inexpensively,” said Elmira Aliakbari, director of natural resource studies at the Fraser Institute.

Summary

- This essay evaluates past carbon emission reduction and the feasibility of eliminating fossil fuels to achieve net-zero carbon by 2050.

- Despite international agreements, government spending and regulations, and technological advancements, global fossil fuel consumption surged by 55 percent between 1997 and 2023. And the share of fossil fuels in global energy consumption has only decreased from nearly 86 percent in 1997 to approximately 82 percent in 2022.

- The first global energy transition, from traditional biomass fuels such as wood and charcoal to fossil fuels, started more than two centuries ago and unfolded gradually. That transition remains incomplete, as billions of people still rely on traditional biomass energies for cooking and heating.

- The scale of today’s energy transition requires approximately 700 exajoules of new non-carbon energies by 2050, which needs about 38,000 projects the size of BC’s Site C or 39,000 equivalents of Muskrat Falls.

- Converting energy-intensive processes (e.g., iron smelting, cement, and plastics) to non-fossil alternatives requires solutions not yet available for largescale use.

- The energy transition imposes unprecedented demands for minerals including copper and lithium, which require substantial time to locate and develop mines.

- To achieve net-zero carbon, affluent countries will incur costs of at least 20 percent of their annual GDP.

- While global cooperation is essential to achieve decarbonization by 2050, major emitters such as the United States, China, and Russia have conflicting interests.

- To eliminate carbon emissions by 2050, governments face unprecedented technical, economic and political challenges, making rapid and inexpensive transition impossible.

Author:

Bjorn Lomborg

Global Warming Policies Hurt the Poor

From the Fraser Institute

Had prices been kept at the same level, an average family of four would be spending £1,882 on electricity. Instead, that family now pays £5,425 per year. The average UK person now consumes just over 10 kWh per day—a low point in consumption not seen since the 1960s.

We are often told by climate campaigners that climate change is especially pernicious because its effects over coming decades will disproportionately affect the poorest people in Canada and the world. Unfortunately, they miss that climate policies are directly hurting the poor right now.

More energy leads to better, healthier, longer lives. Less energy means fewer opportunities. Climate policies demand we pay more for less reliable energy. The impact is greater if you’re poorer: the wealthy might grumble about higher costs but can generally absorb them; the poor are forced to cut back.

For evidence, look to the United Kingdom which has led the world on stiff climate policies and net zero promises for some two decades, sustained by successive governments: its inflation-adjusted electricity price, weighted across households and industry, has tripled from 2003 to 2023, mostly because of climate policies. The total, annual UK electricity bill is now $CAD160 billion, which is $CAD105 billion more than if prices in real terms had stayed unchanged since 2003. This unnecessary increase is so costly that it is twice the entire cost that the UK spends on elementary education. Had prices been kept at the same level, an average family of four would be spending £1,882 on electricity. Instead, that family now pays £5,425 per year.

Over that time, the richest one per cent absorbed the costs and even managed to increase their consumption. But the poorest fifth of UK households saw their electricity consumption decline by a massive one-third.

The effects of climate policies mean the UK can afford less power. The average UK person now consumes just over 10 kWh per day—a low point in consumption not seen since the 1960s. While global individual electricity consumption is steadily increasing, the energy available to an average Brit is sharply decreasing.

Climate policies hurt the poor even in energy-abundant countries like Canada and the United States. Universally, poor people in well-off countries use much more of their limited budgets paying for electricity and heating. US low-income consumers spend three-times more on electricity as a percentage of their total spending than high-income consumers. It’s easy to understand why the elites have no problem supporting electricity or gas price hikes—they can easily afford them.

As mentioned in the article on cold and heat deaths, high energy prices literally kill people—and this is especially true for the poor. Cold homes are one of the leading causes of deaths in winter through strokes, heart attacks, and respiratory diseases. Researchers looked at the natural experiment that happened in the United States around 2010, when fracking delivered a dramatic reduction in costs of natural gas. The massive increase in availability of natural gas drove down the price of heating. The scientists concluded that every single winter, lower energy prices from fracking save about 12,500 Americans from dying. To put this another way, all else being equal, a reversal and hike in energy prices would kill an additional 12,500 people each year.

As bleak as things are for the poor in rich countries, virtue-signaling climate policy has even farther-reaching impacts on the developing world, where people desperately need more access to the cheap and plentiful energy that previously allowed rich nations to develop. In the poor half of the world, more than two billion people have to cook and keep warm with polluting fuels such as dung and wood. This means their indoor air is so polluted it is equivalent to smoking two packs of cigarettes a day—causing millions of deaths each year.

In Africa, electricity is so scarce that the total electricity available per person is much less than what a single refrigerator in the rich world uses. This hampers industrialization, growth, and opportunity. Case in point: The rich world on average has 650 tractors per 50km2, while the impoverished parts of Africa have just one.

But rich countries like Canada—through restrictions on bilateral aid and contributions to global bodies like the World Bank—refuse to fund anything remotely fossil fuel-related. More and more development and aid money is being diverted to climate change, away from the world’s more pressing challenges.

Canada still gets more than three-quarters of its energy (not just electricity) from fossil fuels. Yet, it blocks poor countries from achieving more energy access, with the naïve suggestion that the poor “skip” to intermittent solar and wind with an unreliability that the rich world does not accept to fulfil its own, much bigger needs.

A large 2021 survey of leaders in low- and middle-income countries shows education, employment, peace and health are at the top of their development priorities, with climate coming 12th out of 16 issues. But wealthy countries refuse to pay attention to what poor countries need, in the name of climate change.

The blinkered pursuit of climate goals blinds politicians in rich countries like Canada to the impacts on the poor, both here and across the world in developing nations. Climate policies that cause higher energy costs and push people toward unreliable energy sources disproportionately burden those least able to bear them.

2025 Federal Election

Don’t double-down on net zero again

From the Fraser Institute

In the preamble to the Paris Agreement, world leaders loftily declared they would keep temperature rises “well below 2°C” and perhaps even under 1.5°C. That was never on the cards—it would have required the world’s economies to effectively come to a grinding halt.

The truth is that the “net zero” green agenda, based on massive subsidies and expensive legislation, will likely cost more than CAD$38 trillion per year across the century, making it utterly unattractive to voters in almost every nation on Earth.

When President Trump withdrew the United States from the Paris Climate Agreement for the first time in 2017, then-Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was quick to claim the moral high ground, declaring that “we will continue to work with our domestic and international partners to drive progress on one of the greatest challenges we face as a world.”

Trudeau has now been swept from the stage. On his first day back in office, President Trump signed an executive order that again begins the formal, twelve-month-long process of withdrawing the United States from the Paris Agreement.

It will be tempting for Canada to step anew into the void left by the United States. But if the goal is to make effective climate policy, whoever is Canada’s prime minister needs to avoid empty virtue signaling. It would be easy for Canada to declare again that it’ll form a “coalition of the willing” with Europe. The truth is that, just like last time, that approach would do next to nothing for the planet.

Climate summits have generated vast amounts of attention and breathless reporting giving the impression that they are crucial to the planet’s survival. Scratch the surface, and the results are far less impressive. In 2021, the world promised to phase-down coal. Since then, global coal consumption has only gone up. Virtually every summit has promised to cut emissions but they’ve increased almost every single year, and 2024 reached a new high.

Way before the Paris Agreement was inked, the Kyoto Protocol was once sold as a key part of the solution to global warming. Yet studies show it achieved virtually nothing for climate change.

In the preamble to the Paris Agreement, world leaders loftily declared they would keep temperature rises “well below 2°C” and perhaps even under 1.5°C. That was never on the cards—it would have required the world’s economies to effectively come to a grinding halt.

The truth is that the “net zero” green agenda, based on massive subsidies and expensive legislation, will likely cost more than CAD$38 trillion per year across the century, making it utterly unattractive to voters in almost every nation on Earth.

The awkward reality is that emissions from Canada, the EU, and other countries pursuing climate policies matter little in the 21st century. Canada likely only makes up about 1.5 per cent of the world’s emissions. Add together Canada’s output with that of every single country of the rich-world OECD, and this only makes up about one-fifth of global emissions this century, using the United Nations’ ‘middle of the road’ forecast. The other four-fifths of emissions come mostly from China, India and Africa.

Even if wealthy countries like Canada impoverish themselves, the result is tiny — run the UN’s standard climate model with and without Canada going net-zero in 2050, and the difference is immeasurable even in 2100. Moreover, much of the production and emissions just move to the Global South—and even less is achieved.

One good example of this is the United Kingdom, which—like Prime Minister Trudeau once did—has leaned into climate policies, suggesting it would lead the efforts for strong climate agreements. British families are paying a heavy price for their government going farther than almost any other in pursuing the climate agenda: just the inflation-adjusted electricity price, weighted across households and industry, has tripled from 2003 to 2023, mostly because of climate policies. This need not have been so: the US electricity price has remained almost unchanged over the same period.

The effect on families is devastating. Had prices stayed at 2003 levels, an average family-of-four would now be spending CAD$3,380 on electricity—which includes indirect industry costs. Instead, it now pays $9,740 per year.

Rising electricity costs make investment less attractive: European businesses pay triple US electricity costs, and nearly two-thirds of European companies say energy prices are now a major impediment to investment.

The Paris Treaty approach is fundamentally flawed. Carbon emissions continue to grow because cheap, reliable power, mostly from fossil fuels, drives economic growth. Wealthy countries like Canada, the US, and European Union members have started to cut emissions—often by shifting production elsewhere—but the rest of the world remains focused on eradicating poverty.

Poor countries will rightly reject making carbon cuts unless there is a huge flow of “climate aid” from rich nations, and want trillions of US dollars per year. That won’t happen. The new US government will not pay, and the other rich countries cannot foot the bill alone.

Without these huge transfers of wealth, China, India and many other developing countries will disavow expensive climate policies, too. This potentially leaves a rag-tag group led by a few Western European progressive nations, which can scarcely afford their own policies and have no ability to pay off everyone else.

When the United States withdrew from the Paris Agreement in 2017, Canada’s doubling down on the Paris Treaty sent the signal that it would be worthwhile spending hundreds of trillions of dollars to make no real difference to temperatures. We fool ourselves if we pretend that doing so for a second time will help the planet.

We need to realize that fixing climate change isn’t about sanctimonious summits, lofty speeches, and bluster. In coming weeks I’ll outline the case for efficient policies like innovation, adaptation and prosperity.

-

illegal immigration2 days ago

illegal immigration2 days agoDespite court rulings, the Trump Administration shows no interest in helping Abrego Garcia return to the U.S.

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoEuthanasia is out of control in Canada, but nobody is talking about it on the campaign trail

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoConservative MP Leslyn Lewis warns Canadian voters of Liberal plan to penalize religious charities

-

Education2 days ago

Education2 days agoSchools should focus on falling math and reading grades—not environmental activism

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

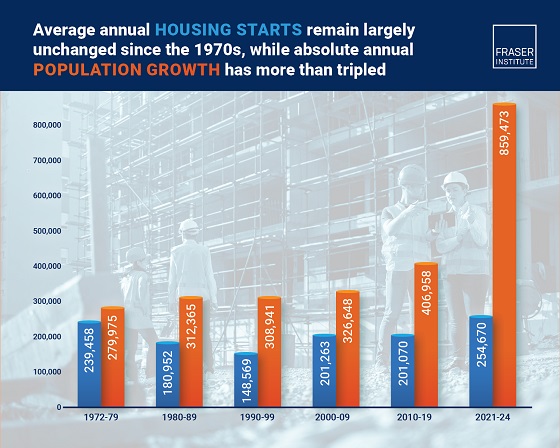

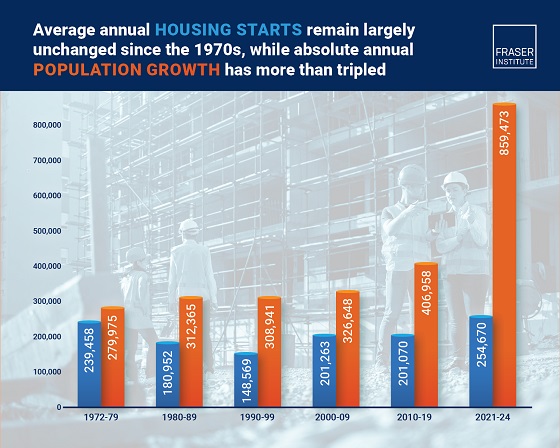

2025 Federal Election2 days agoHousing starts unchanged since 1970s, while Canadian population growth has more than tripled

-

2025 Federal Election21 hours ago

2025 Federal Election21 hours agoRCMP Whistleblowers Accuse Members of Mark Carney’s Inner Circle of Security Breaches and Surveillance

-

Autism1 day ago

Autism1 day agoAutism Rates Reach Unprecedented Highs: 1 in 12 Boys at Age 4 in California, 1 in 31 Nationally

-

Bjorn Lomborg2 days ago

Bjorn Lomborg2 days agoGlobal Warming Policies Hurt the Poor