Fraser Institute

Government meddling contributes to doctor exodus in Quebec

From the Fraser Institute

By Bacchus Barua and Yanick Labrie

They have not left Quebec’s health-care system but rather have opted out of the province’s publicly-financed framework to provide care to their patients privately.

Quebec’s health minister recently came under fire after reports revealed a record number of physicians left the province’s public system to practise privately. Less discussed are the reasons why physicians made this choice.

Indeed, it turns out that ill-conceived attempts to protect publicly-funded health care by the Trudeau government and successive provincial governments may have contributed to the increasing numbers of physicians opting-out.

To be clear, the 780 physicians in question account for about four per cent of physicians in the province. However, this represents a 22 per cent increase in the number of physicians leaving the public system compared to the previous year—and is part of a growing trend. More importantly, they have not left Quebec’s health-care system but rather have opted out of the province’s publicly-financed framework to provide care to their patients privately.

Why?

One reason, is because governments have forced them to do so.

Until recently, physicians in Quebec (including those who practiced in the public sector) were allowed to charge patients so-called “accessory-fees” in certain instances—for example, if the service was either not covered or insufficiently reimbursed by the government’s fee schedule.

However, the federal Canada Health Act (CHA) clearly states that “extra-billing” of this nature, when charged by physicians who also bill the public system, must result in dollar-for-dollar deductions in federal health-care transfer payments to the province. In other words, the CHA encourages provincial efforts to effectively force doctors to choose between the public and private system if any out-of-pocket expenses are involved.

And so, under financial threat by the Trudeau government, Quebec eventually clamped down on such fees charged by physicians who worked in the public system.

Consequently, physicians who relied on these payments to cover a portion of their operating costs faced an unfortunate choice—stay in the public system at the risk of financial ruin or opt-out entirely and practise exclusively in the private sector.

For many, the choice was obvious. One study found that by 2019 “an additional 69 specialist physicians opted out after the 2017 clampdown on double billing [sic] than previous trends would have predicted.” Several clinics offering endoscopy and colonoscopy services simply closed their doors. Quebecers also ended up with a less convenient health-care experience following this clamp down, as evidenced by the reduction in clinic-provided services that followed.

This attitude to extra-billing stands in stark contrast to the situation in other universal health-care countries such as Australia where consultations with specialists are usually only partially (85 per cent) covered by the universal plan. In fact, physicians (family doctors and specialists) can generally set fees above the government’s fee schedule so long as they forgo the convenience of directly billing the government (i.e. patients claim reimbursement after the fact). Notably, Australia’s health-care system costs less than Canada’s in total (including these private payments) yet delivers more rapid access to health-care services with a greater availability of medical professionals, hospital beds, and diagnostic and surgical technologies.

More generally, a recent study found 22 of 28 universal health-care countries require patients to share a portion of the cost of treatment (with generous protections for vulnerable groups). These include deductibles (an amount individuals must pay before insurance coverage kicks in), co-insurance payments (the patient pays a certain percentage of treatment cost) and copayments (the patient pays a fixed amount per treatment). Crucially, many of these countries including Australia, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland also have shorter wait times than we endure.

In these countries, physicians are also generally allowed to practise both in publicly-funded universal settings and private settings (a policy known as “dual practice”) rather than having their activities restricted to one setting only. In other words, Canada’s federal restrictions on cost-sharing and extra-billing (such as Quebec’s accessory fees) and provincial barriers to dual-practice place our universal system in the minority of a small cohort of countries that are not particularly known for stellar performance.

The looming threat of further reductions in federal cash transfers, under the CHA, has led to provinces such as Quebec imposing increasingly restrictive conditions on physicians in the public system. And in response, physicians—by opting-out—are indicating that they’ve had enough.

It’s ironic that the very groups intent on supposedly “protecting public health care” by forcing physicians to choose between the public and private systems have enforced policies that may very well lead to the public system’s continued demise.

Authors:

Alberta

Falling resource revenue fuels Alberta government’s red ink

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill

According to this week’s fiscal update, amid falling oil prices, the Alberta government will run a projected $6.4 billion budget deficit in 2025/26—higher than the $5.2 billion deficit projected earlier this year and a massive swing from the $8.3 billion surplus recorded in 2024/25.

Overall, that’s a $14.8 billion deterioration in Alberta’s budgetary balance year over year. Resource revenue, including oil and gas royalties, comprises 44.5 per cent of that decline, falling by a projected $6.6 billion.

Albertans shouldn’t be surprised—the good times never last forever. It’s all part of the boom-and-bust cycle where the Alberta government enjoys budget surpluses when resource revenue is high, but inevitably falls back into deficits when resource revenue declines. Indeed, if resource revenue was at the same level as last year, Alberta’s budget would be balanced.

Instead, the Alberta government will return to a period of debt accumulation with projected net debt (total debt minus financial assets) reaching $42.0 billion this fiscal year. That comes with real costs for Albertans in the form of high debt interest payments ($3.0 billion) and potentially higher taxes in the future. That’s why Albertans need a new path forward. The key? Saving during good times to prepare for the bad.

The Smith government has made some strides in this direction by saving a share of budget surpluses, recorded over the last few years, in the Heritage Fund (Alberta’s long-term savings fund). But long-term savings is different than a designated rainy-day account to deal with short-term volatility.

Here’s how it’d work. The provincial government should determine a stable amount of resource revenue to be included in the budget annually. Any resource revenue above that amount would be automatically deposited in the rainy-day account to be withdrawn to support the budget (i.e. maintain that stable amount) in years when resource revenue falls below that set amount.

It wouldn’t be Alberta’s first rainy-day account. Back in 2003, the province established the Alberta Sustainability Fund (ASF), which was intended to operate this way. Unfortunately, it was based in statutory law, which meant the Alberta government could unilaterally change the rules governing the fund. Consequently, by 2007 nearly all resource revenue was used for annual spending. The rainy-day account was eventually drained and eliminated entirely in 2013. This time, the government should make the fund’s rules constitutional, which would make them much more difficult to change or ignore in the future.

According to this week’s fiscal update, the Alberta government’s resource revenue rollercoaster has turned from boom to bust. A rainy-day account would improve predictability and stability in the future by mitigating the impact of volatile resource revenue on the budget.

Energy

Mistakes and misinformation by experts cloud discussions on energy

From the Fraser Institute

By Jason Clemens and Elmira Aliakbari

The new agreement (MOU) between the Carney and Alberta governments sets the foundation for a pipeline from Alberta to the British Columbia coast, at least conceptually. Unfortunately, many politicians and commentators, including the bureau chiefs for the Globe and Mail and Toronto Star, continue to get many energy facts wrong, which impairs the discussions of how best the country can and should move forward to capitalize on our natural resources.

For example, commentors often wrongly describe the tanker ban on the west coast (C-48) as a general ban on oil tankers. But in reality, the law only applies to tankers docking at Canadian ports. It does not and cannot prevent tankers from travelling the west coast so long as they’re not stationing at Canadian ports. This explains the continued oil tanker traffic in the northwest region for tankers docking in U.S. ports in Alaska. Simply put, there is not a general tanker ban on the west coast.

Commentators also continue to misrepresent the current capacity on the expanded Trans Mountain pipeline (TMX). According to the Canada Energy Regulator (CER), the average utilization of the TMX since it came online in June 2024 is 82 per cent (reaching as high as 89 per cent in March 2025). So, while there’s some room for additional oil transportation via TMX, it’s nowhere close to the “doubling” being discussed in central Canada. Critically, though, according to the CER, from “June 2024 to June 2025, committed capacity was effectively fully utilized each month, averaging 99% utilization.”

Similarly, there’s a misunderstanding by many in central Canada regarding the potential restart of the Keystone XL pipeline, which apparently President Trump is keen on. Keystone would not diversify Canada’s exports because while oil does make its way down to the southern U.S. where it can be exported, the actual sale of Canadian oil is to U.S. refineries, so our reliance on the U.S. as our near-sole export market would continue unless a west and/or east coast pipeline is developed.

There also continues to be an artificial and costly connection made between Ottawa removing the arbitrary emissions cap on greenhouse gases by the oil and gas sector and the approval of a new pipeline with the proposed Pathways carbon capture project, which is a collaboration between five of Canada’s largest oil producers. This connection was galvanized in the MOU.

The idea behind the project is to reduce (conceptually) the amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) emitted from oil extraction and transportation projects linked with Pathways. The Pathways project produces no economic value or product—it simply collects and stores GHG emissions—and reports suggest the total cost for the first phase of the project will reach $16.5 billion.

Should Canadians care about adding costs related to GHG mitigation? There are several factors to consider. First, Canada is already a low-GHG emitting producer of oil. According to the Carney government’s first budget (page 105, chart 1.5 which ranks the world’s 20 top oil producers based on their GHG emissions per unit of output), Canada already ranks 7th-lowest in terms of emissions. And more importantly, it’s lower than every country—Venezuela, Russia, Iraq and Mexico—that produces a similar type of oil as Canada. Any resources spent further reducing GHG emissions via carbon capture will result in small incremental gains contrasted with large costs (again, at least $16.5 billion). A number of analysts have already raised concerns about the investment and competitiveness implications of increasing the cost structures for Alberta producers.

Second, according to the federal government, in 2022 Canada produced 1.4 per cent of global GHG emissions, and the oil and gas sector produced roughly one-quarter of those emissions. In other words, if Canada eliminated all GHG emissions from the oil sector via carbon capture, the process would consume vast amounts of scarce resources (i.e. money) and result in a nearly undetectable change in global GHG emissions. One can only conclude that this is much more about international virtue-signalling than the actual economics and environmental implications of Canada’s potential energy projects.

At a time when Canada is struggling with crisis levels of private business investment, falling living standards and as the Bank of Canada described, a break-the-glass crisis in productivity growth, it’s clearly not wise to spend tens of billions of dollars on projects that might make politicians and bureaucrats feel better and enable them to use near Orwellian language like “zero-emissions oil” but that actually deliver almost no detectable environmental benefits.

To borrow our prime minister’s favourite phrase, kickstarting Canada’s oil and gas sector is the easiest way to catalyze economic growth given our vast energy reserves, know-how in the sector, and high productivity. To do so, we need a national dialogue rooted in facts.

-

Alberta8 hours ago

Alberta8 hours agoFrom Underdog to Top Broodmare

-

armed forces2 days ago

armed forces2 days ago2025 Federal Budget: Veterans Are Bleeding for This Budget

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta and Ottawa ink landmark energy agreement

-

Artificial Intelligence2 days ago

Artificial Intelligence2 days agoTrump’s New AI Focused ‘Manhattan Project’ Adds Pressure To Grid

-

International1 day ago

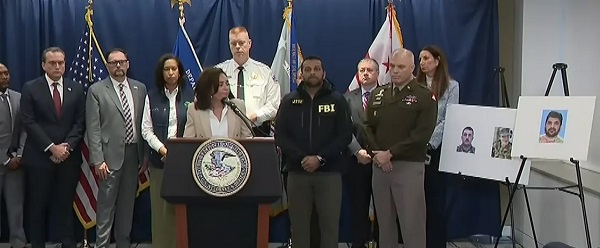

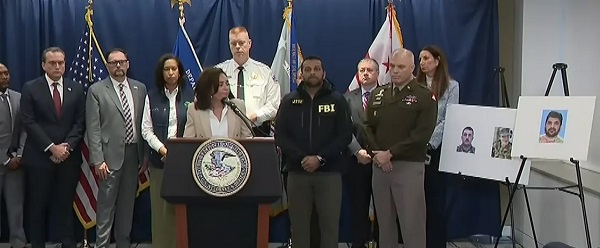

International1 day agoAfghan Ex–CIA Partner Accused in D.C. National Guard Ambush

-

Carbon Tax1 day ago

Carbon Tax1 day agoCanadian energy policies undermine a century of North American integration

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoIdentities of wounded Guardsmen, each newly sworn in

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoTrump Admin Pulls Plug On Afghan Immigration Following National Guard Shooting