Gerry Feehan

Egypt: Sailing the Nile Part 1 by Gerry Feehan

Sure, there’s no travel now, but one day, when the world opens up, we will travel again. In the meantime, enjoy the first in a two-part series “Sailing the Nile”

The Nile River is a mind-boggling 6853 km long. It is the longest river in the world. Mind you we were only sailing about 200 km of it, from Luxor to Aswan, on an Egyptian dahabiya. But since we were relying on the prevailing north wind to carry us upstream—to the south—even that took nearly a week.

Dahabiyas are shallow-bottomed, barge-like vessels. These two-masted craft have been plying the waters of the Nile, in one form or another, for thousands of years. We were on the Malouka, a 45-meter long beauty, part of the four-boat Nour el Nil fleet. For the entire voyage, all four boats sailed together in a colourful flotilla. https://www.nourelnil.com/

Our captain was Humpty Dumpty (the crew had given each other very entertaining nicknames). Humpty was a musical fellow. When he wasn’t shouting orders he was humming quietly to himself. As my travels have repeatedly confirmed, music is the world’s great unifier. Thus, on our second evening aboard, I uncased my ever-present ukulele and began strumming a few tunes. Soon, the captain and a few other crewmembers wandered up from below deck, listening appreciatively, attentively—and patiently.

Abandoning our eggs, we all scrambled from the table and donned bathing attire.

Then it was their turn. In moments the entire crew had gathered on deck, instruments in hand. They began clapping as the captain sang out an Arabic folk song. The loud thumping of the cook’s doumbec filled the Nile valley with contagious percussion. The floorboards reverberated as every soul on board bounced wildly in unison. Our quiet jam session on a soft Egyptian night had quickly evolved into a raucous international jamboree. It was magical.

In the morning we were enjoying a reflective, leisurely breakfast when someone shouted, ‘There’s a woman floating in the river!’ The lady casually waved as she drifted by. It was Eleanor, one of Nour el Nil’s owners. Eleanor’s cabin was on the Malouka’s sister ship, the Meroe. We were invited to join Eleanor in the water. I had no idea that swimming in the Nile was safe—or part of the agenda.

Abandoning our eggs, we all scrambled from the table and donned bathing attire. The procedure was simple: walk a few hundred meters upstream, jump in and simply go with the flow. Drift down to the dahabiya, swim to shore and… repeat. This unexpected treat—and respite from the hot Egyptian sun—quickly became a daily ritual. Surprisingly, the Nile River is not overly wide. But it has a subtle incessant strength. A dip in this great watercourse reveals its unmistakable power. Each of us tried futilely to buck the current and swim upstream. None made any headway, all eventually succumbing to the Nile’s deep, relentless, perpetual force.

Ancient Egyptians relied on this coincidence of opposing wind and current to build the greatest civilization the world had ever known. It is what enabled the construction of the pyramids 4500 years ago. Vast blocks of granite and sandstone were quarried and, during the annual flood, floated downstream and unloaded. Then the barges were sailed back upstream and loaded anew. The Great Pyramid of Cheops near Cairo contains over two million blocks, each weighing in excess of a tonne, every stone stacked in place by hand. That’s a lot of barging—not to mention the heavy lifting.

There is no more luxurious—or relaxing way—to see Egypt and appreciate its spectacular ancient tombs and temples, than to embark on a quiet sail up the Nile on a dahabiya. Muslim rulers in the middle ages ostentatiously gilded these barges the colour of the sun. The name is thus derived from the Arabic word for gold.

Each day we moved a little further south. We’d dock, disembark and, after enduring a gauntlet of incessant, tenacious, persistent street hawkers, we’d be in the portal of one of ancient Egypt’s incredible monuments. All these sites are located just a short walk from shore, above the high-water mark of the historical Nile flood. First we visited Esna, then Al-Kab, then Edfu and Horemheb. Our final stop was Kom-Ombo and its Crocodile Museum, where 3000 year-old mummified reptiles stared at us, teeth bared, looking malevolently alive. The Pharaohs venerated these beasts, preserving them for their mutual journey to the afterlife.

Temple guard

Kom-Ombo

At each stop we were met on shore by Adele, a young Egyptologist, who guided us through the complex history of these wonders. He patiently explained the ancient hieroglyphs that adorned the sandstone walls—but only after our group gave him our complete attention. Any noisy transgressors received a stony stare until they were embarrassed into silence. Then in a quiet but commanding baritone the lesson would begin. And god forbid you were caught snapping a photo of a frieze from the middle kingdom during one of his talks. Another cold glare would ensue, together with the admonition, “Time for pictures later.”

Adele explaining a cartouche

On the hike to Al-Kab, I noticed Adele fidgeting with something in his hands. “Why the worry beads?” I asked. “Prayer beads,” he corrected. He didn’t look like the devout type. “I’m trying to quit smoking,” he explained sheepishly.

Inside the tomb, Adele was showing us how to read a 30-century-old cartouche carved into the stone, pointing out a few of the multitude of gods worshiped by the early Egyptians. Osiris, god of the dead, Horus, with his falcon head and Isis, Horus’s mother. We all stood, obediently quiet in the dim sweltering closeness of the crypt. Then with a flashlight he pointed out some additional markings in the rock: ‘John Edwards 1819.’ We looked closer and saw many other similar autographs. British soldiers had clumsily scratched graffiti into these magnificent ancient works 200 years ago.

Kilroy, it seems, has been just about everywhere.

Next time: Part 2: Sailing the Nile on a Dahabiya.

Exodus Travel skillfully handled every detail of our Egypt adventure: www.exodustravels.com/

Gerry Feehan is an award-winning travel writer and photographer. He and his wife Florence now live in Kimberley, BC!

Gerry Feehan is an award-winning travel writer and photographer. He and his wife Florence now live in Kimberley, BC!

Thanks to Kennedy Wealth Management and Ing and McKee Insurance for sponsoring this series. Click on their ads and learn more about these long-term local businesses.

Click to read more travel stories.

We will travel again but in the meantime, enjoy Gerry’s ‘Buddy Trip to Ireland’

Gerry Feehan

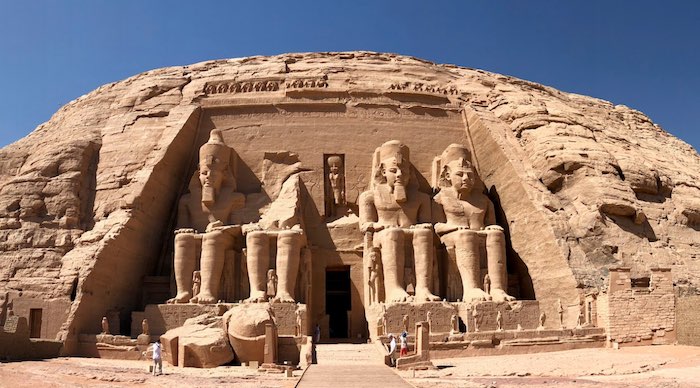

Abu Simbel

Abu Simbel is a marvel of ancient and modern engineering

I love looking out the window of an airplane at the earth far below, seeing where coast meets water or observing the eroded remains of some ancient formation in the changing light. Alas, the grimy desert sand hadn’t been cleaned from the windows of our EgyptAir jet, so we couldn’t see a thing as we flew over Lake Nasser en route to Abu Simbel. I was hopeful that this lack of attention to detail would not extend to other minor maintenance items, such as ensuring the cabin was pressurized or the fuel tank full.

We had just spent a week on a dahabiya sailboat cruising the Nile River, and after disembarking at Aswan, were headed further south to see one of Egypt’s great

monuments. There are a couple of ways to get to Abu Simbel from Aswan. You can ride a bus for 4 hours through the scorched Sahara Desert, or you can take a plane for the short 45-minute flight.

Opaque windows notwithstanding, I was glad we had chosen travel by air. Abu Simbel is spectacular, but there’s really not much to see except the monument itself and a small adjacent museum. So most tourists, us included, make the return trip in a day. And fortunately we had Sayed Mansour, an Egyptologist, on board. Sayed was there to explain all and clear our pained expressions.

Although it was early November, the intense Nubian sun was almost directly overhead, so Sayed led us to a quiet, shady spot where he began our introduction to

Egyptian history. Abu Simbel is a marvel of engineering — both modern and ancient. The temples were constructed during the reign of Ramses II. Carved from solid rock in a sandstone cliff overlooking the mighty river, these massive twin temples stood sentinel at a menacing bend in the Nile — and served as an intimidating obstacle to would-be invaders — for over 3000 years. But eventually Abu Simbel fell into disuse and succumbed to the inevitable, unrelenting Sahara. The site was nearly swallowed by sand when it was “rediscovered” by European adventurers in the early 19 th century. After years of excavation and restoration, the monuments resumed their original glory.

Then, in the 1960’s, Egyptian president Abdel Nasser decided to construct a new “High Dam” at Aswan. Doing so would create the largest man-made lake in the

world, 5250 sq km of backed-up Nile River. This ambitious project would bring economic benefit to parched Egypt, control the unpredictable annual Nile flood and also supply hydroelectric power to a poor, under-developed country. With the dam, the lights would go on in most Egyptian villages for the first time. But there were also a couple of drawbacks, which were conveniently swept under the water carpet by the government. The new reservoir would displace the local Nubian population whose forbearers had farmed the fertile banks of the Nile River for millennia. And many of Egypt’s greatest monuments and tombs would be forever submerged beneath the deep new basin — Abu Simbel included. But the government proceeded with the dam, monuments be damned.

Only after the water began to rise did an international team of archaeologists, scientists — and an army of labourers — begin the process of preserving these

colossal wonders. In an urgent race against the rising tide, the temples of Abu Simbel were surgically sliced into gigantic pieces, transported up the bank to safety and reassembled. The process was remarkable, a feat of engineering genius. And today the twin edifices, honouring Ramses and his wife Nefertari remain, gigantic, imperious and intact. But instead of overlooking a daunting corner of the Nile, this UNESCO World Heritage site now stands guard over a vast shimmering lake.

Sayed led us into the courtyard from our shady refuge and pointed to the four giant Colossi that decorate the exterior façade of the main temple. These statues of

Ramses were sculpted directly from Nile bedrock and sat stonily observing the river for 33 centuries. It was brutally hot under the direct sun. I was grateful for the new hat I had just acquired from a gullible street merchant. Poor fellow didn’t know what hit him. He started out demanding $40, but after a prolonged and brilliant negotiating session, I closed the deal for a trifling $36. It was difficult to hold back a grin as I sauntered away sporting my new fedora — although the thing did fall apart a couple of days later.

Sayed walked us toward the sacred heart of the shrine and lowered his voice. Like all Egyptians, Sayed’s native tongue is Arabic. But, oddly, his otherwise perfect English betrayed a slight cockney accent. (Sayed later disclosed that he had spent a couple of years working in an East London parts factory.) He showed us how the great hypostyle hall of the temple’s interior is supported by eight enormous pillars honouring Osiris, god of the underworld.

Exploring the inner temple

Nefertari

Sayed then left us to our devices. There were no other tourists. We had this incredible place to ourselves. In the dim light, we scampered amongst the sculptures

and sarcophagi, wandering, hiding and giggling as we explored the interior and its side chambers. At the far end lay the “the holiest of holies” a room whose walls were adorned with ornate carvings honouring the great Pharaoh’s victories — and offering tribute to the gods that made Ramses’ triumphs possible.

Exterior photographs of Abu Simbel are permitted, but pictures from within the sanctuary are verboten — a rule strictly enforced by the vigilant temple guardians — unless you offer a little baksheesh… in which case you can snap away to your heart’s content. Palms suitably greased, the caretakers are happy to pose with you in front of a hidden hieroglyph or a forbidden frieze, notwithstanding the stern glare of Ramses looking down from above.

A little baksheesh is key to holding the key

After our brief few hours at Abu Simbel, we hopped back on the plane. The panes weren’t any clearer but, acknowledging that there really wasn’t much to see in the Sahara — and that dirty airplane windows are not really a bona fide safety concern — I took time on the short flight to relax and bone up on Ramses the Great, whose mummified body awaited us at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Exodus Travel skilfully handled every detail of our Egypt adventure: www.exodustravels.com/

Gerry Feehan is an award-winning travel writer and photographer. He lives in Kimberley, BC.

Thanks to Kennedy Wealth Management for sponsoring this series. Click on the ads and learn more about this long-term local business.

Gerry Feehan

Cairo – Al-Qahirah

The Pyramids of Giza

The first thing one notices upon arrival in Egypt is the intense level of security. I was screened once, scanned twice and patted down thrice between the time we landed at the airport and when we finally stepped out into the muggy Cairo evening. At our hotel the scrutiny continued with one last investigation of our luggage in the lobby. Although Egyptian security is abundant in quantity, the quality is questionable. The airport x-ray fellow, examining the egg shaker in my ukulele case, sternly demanded, “This, this, open this.” When I innocently shook the little plastic thing to demonstrate its impermeability he recoiled in horror, but then observed it with fascination and called over his supervisor. Thus began an animated, impromptu percussion session. As for the ukulele, it was confiscated at hotel check-in and imprisoned in the coat check for the duration of our Cairo stay. The reasons proffered for the seizure of this innocuous little instrument ranged from “safety purposes” to “forbidden entertainment”. When, after a very long day, we finally collapsed exhausted into bed, I was shaken — but did not stir.

Al-Qahirah has 20 million inhabitants, all squeezed into a thin green strip along the Nile River. Fading infrastructure and an exponential growth in vehicles have contributed to its well-deserved reputation as one of the world’s most traffic-congested cities. The 20km trip from our hotel in the city center, to the Great Pyramid of Cheops at Giza across the river, took nearly two hours. The driver smiled, “Very good, not rush hour.”

Our entrance fee for the Giza site was prepaid but we elected to fork out the extra Egyptian pounds to gain access to the interior of the Great Pyramid. Despite the up-charge — and the narrow, dark, claustrophobic climb – the reward, standing in Cheop’s eternal resting place, a crypt hidden deep inside the pyramid, was well worth it. We also chose to stay after sunset, dine al fresco in the warm Egyptian evening, and watch the celebrated ‘sound and light’ performance. The show was good. The food was marginal. Our waiter’s name was Fahid. Like many devout Muslim men, he sported a zabiba, or prayer bump, a callus developed on the forehead from years of prostration. Unfortunately throughout the event Fahid hovered over us, attentive to the point of irritation, blocking our view of the spectacle while constantly snapping fingers at his nervous underlings. The ‘son et lumière’ show was a little corny, but it’s pretty cool to see a trio of 4500-year-old pyramids – and the adjoining Great Sphinx — illuminated by 21 st century technology.

The Great Sphinx

Giza at nightThe next night our group of six Canucks attended an Egyptian cooking class. Our ebullient hostess was Anhar, (‘the River’ in Arabic). Encouraged by her contagious enthusiasm, we whipped up a nice tabouli salad, spicy chicken orzo soup and eggplant moussaka. We finished up with homemade baklava. Throughout the evening, Anhar quizzed us about the ingredients, the herbs and spices, their origins and proper method of preparation. Anyone who answered correctly was rewarded with her approving nod and a polite clap. Soon a contest ensued. Incorrect answers resulted in a loud communal ‘bzzzt’ — like the sound ending a hockey game. It’s not polite to blow one’s own horn, but the Feehan contingent acquitted themselves quite nicely. If I still had her email, Anhar could confirm this.

Cairo was not the highlight of our three-week Egyptian holiday, but a visit to the capital is mandatory. First there’s the incredible Pyramids. But as well there’s the Egyptian Museum that houses the world’s largest collection of Pharaonic antiquities including the golden finery of King Tutankhamen and the mummified remains of Ramses the Great. Ramses’ hair is rust coloured and thinning a little, but overall he looks pretty good for a guy entering his 34 th century.

Ramses the Great

Then there’s Khan el-Khalili, the old souk or Islamic bazaar. We strolled its ancient streets and narrow meandering alleyways, continually set upon by indefatigable street hawkers. “La shukraan, no thanks,” we repeated ineffectually a thousand times. The souk’s cafes were jammed. A soccer match was on. The ‘beautiful game’ is huge in Egypt. Men and women sat, eyes glued to the screen, sipping tea and inhaling hubbly bubbly.

The Old Souk Bazaar

Selfies, Souk style

An aside. When traveling in Egypt, be sure to carry some loose change for the hammam (el baño for those of you who’ve been to Mexico). At every hotel, restaurant, museum and temple — even at the humblest rural commode — an attendant vigilantly guards the lavatory. And have small bills for the requisite baksheesh. You’re not getting change.

After our evening in the souk we had an early call. Our guide Sayed Mansour met us at 6am in the hotel lobby. “Yella, yella. Hurry, let’s go,” he said. “Ana mish bahasir – I’m not joking.” “Afwan,” we said. “No problem,” and jumped into the van. As we pulled away from the curb Sayed began the day’s tutorial, reciting a poem by Percy Blythe Shelly:

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

And we were off, through the desert, to Alexandria. Founded by Alexander the Great in 332 BC, Egypt’s ancient capital was built on the Nile delta, where the world’s longest river meets the Mediterranean Sea. The day was a bit of a bust. The city was once renowned for its magnificent library and the famed Lighthouse of Alexandria. But the former burnt down shortly after Christ was born and the latter — one of the original seven wonders of the ancient world – toppled into the sea a thousand years ago. Absent some interesting architecture, a nice view of the sea from the Citadel — and Sayed’s entertaining commentary — Alexandria wasn’t really worth the long day trip. Besides, we needed to get back to Cairo and pack our swimwear. Sharm el Sheikh and the warm waters of the Red Sea were next up on the Egyptian agenda.

Gerry with some Egyptian admirers

Exodus Travel skilfully handled every detail of our trip: www.exodustravels.com And, if you’re thinking of visiting Egypt, I can suggest a nice itinerary. No sense reinventing the pyramid: [email protected]

Gerry Feehan is an award-winning travel writer and photographer. He lives in Kimberley, BC.

Thanks to Kennedy Wealth Management for sponsoring this series. Click on the ads and learn more about this long-term local business.

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoIs HNIC Ready For The Winnipeg Jets To Be Canada’s Heroes?

-

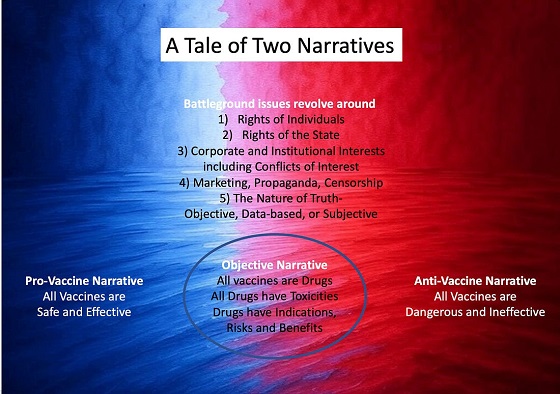

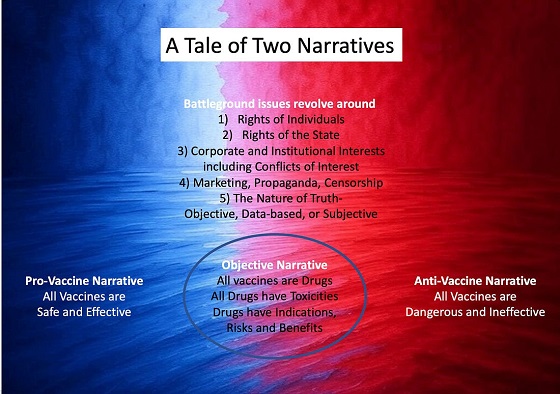

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoCOVID virus, vaccines are driving explosion in cancer, billionaire scientist tells Tucker Carlson

-

Dr. Robert Malone2 days ago

Dr. Robert Malone2 days agoThe West Texas Measles Outbreak as a Societal and Political Mirror

-

illegal immigration1 day ago

illegal immigration1 day agoDespite court rulings, the Trump Administration shows no interest in helping Abrego Garcia return to the U.S.

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoHorrific and Deadly Effects of Antidepressants

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoConservative MP Leslyn Lewis warns Canadian voters of Liberal plan to penalize religious charities

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoEuthanasia is out of control in Canada, but nobody is talking about it on the campaign trail

-

Education1 day ago

Education1 day agoSchools should focus on falling math and reading grades—not environmental activism