Frontier Centre for Public Policy

The post-national cult of diversity promotes authoritarian intolerance

From the Frontier Center for Public Policy

“There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada. … Those qualities are what make us the first post-national state.” — Justin Trudeau, 2015.

Throughout history, populations with sufficient historical, geographic, linguistic, economic, religious, and cultural attachments have flourished within the borders of unified nation-states.

Few modern nation-states fit a uniform definition. In countries such as Canada and the United States, two or more nations, regions, colonies, and tribes learned to prosper together within a negotiated constitutional order.

Not all nations insist on total sovereignty as a condition of their existence. Former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper acknowledged this when he put forward a parliamentary motion recognizing that the Québécois form a historical “nation” within the united Dominion of Canada.

In 2006, Members of Parliament overwhelmingly supported Mr. Harper’s motion, but it was notable that Justin Trudeau, a rising star in the Liberal Party of Canada, regarded the recognition of a Quebec nation as an “old idea from the 19th century.” He said it was “based on a smallness of thought.”

For the cosmopolitan left, the period between November 2015 and November 2016 was a pivotal moment in history. A U.S. president who had rejected the idea of “American exceptionalism” and a Canadian Prime Minister who said his country had “no core identity” were in perfect accord with a growing cabal of international plutocrats who disapproved of nationalism and looked forward to the emergence of a borderless, new world order.

Globalists were convinced that a higher form of humanity could be achieved through a new trifecta of values known as “diversity, equity, and inclusion.” The only people standing in their way were pesky British Brexiters and Donald J. Trump.

Modern Origins of Anti-Nationalism

The post-modern left has always insisted that patriotism is a precursor to fascism. Since the late 1960s, Western intellectuals have deceptively linked nationalism and patriotism with the cultural values of Nazi Germany. For neo-Marxist intellectuals, affirming the merits of one’s nation is symptomatic of an authoritarian personality.

Following the fall of the Iron Curtain in the late 20th century, “global integration” became an increasingly popular vision among international policy experts. World Economic Forum patricians proposed a superior morality to be guided by a “Great Reset.”

The left insisted that problems such as climate change, inequality, racism, and poverty called for bold solutions. As a result, a “one-world government” paradigm came to occupy the center of academic thought. Universities in North America and Europe routinely advertised for positions in “global governance,” a term that few would have recognized a decade earlier.

The presumed genius of leaders such as Mr. Trudeau and President Obama promised to usher in a new era of diversity and inclusion that would make our world a kinder and gentler place.

The Old Diversity and the New

Over recent years, several scholars have adopted a more skeptical view of the post-national bromides being passed off as “diversity and inclusion.”

For example, University of Kent emeritus professor of sociology Frank Furedi argues that “diversity” is not “a value in and of itself.” He regards the present-day version of diversity as the foundation for a new form of authoritarianism.

In a January Substack article, Mr. Furedi pointed out that the meaning of diversity has been fundamentally altered.

This older form of diversity promised that the cultural freedom of local districts, tribes, races, religions, and immigrant communities could be respected within a justly established legal and constitutional order. It was a model that inspired the loyalty of citizens in modern nation-states such as the United States and Canada.

Post-national diversity means something entirely different. Mr. Furedi argues that “the current version of diversity is abstract and often administratively created. It is frequently imposed from above and affirmed through rules and procedure.”

He goes on to assert: “The artificial character of diversity is demonstrated by its reliance on legal and quasi-legal instruments. There is a veritable army of bureaucrats and inspectors who are assigned the role of enforcing diversity related rules. The unnatural and artificial character of diversity is illustrated by the fact that it must be taught.”

Dogmatic Diversity and the Decline of Freedom

Over the past 75 years, the left has promoted diversity as a remedy for discrimination. By the late 1960s, it had acquired a sacred importance. Mr. Furedi contends that “the main driver of this development was the politicisation of identity.”

He quotes the philosopher Christopher Lasch: “In practice, diversity turns out to legitimise a new dogmatism, in which rival minorities take shelter behind a set of beliefs impervious to rational discussion.”

Unfortunately, Mr. Furedi writes, “diversity has proved to be an enemy of tolerance.”

Radical proponents of diversity and inclusion reject debate and demand conformity. They have no qualms about limiting fundamental liberties, particularly free speech. The totalitarian temptations within this cult are akin to the impulses of an ancient creed or a communist dictatorship. No one is free to disagree, and there is little kindness in a dogma that has become the foundational value for 21st-century authoritarians.

Ten years ago, post-nationalist politicians such as President Obama and Mr. Trudeau found it easy to sell woke elites the same unfounded assumptions they had already acquired in university.

Today, free-thinking common folks are becoming considerably tired of serving the appetites of false prophets.

William Brooks is a Senior Fellow at Frontier Centre For Public Policy. This commentary was first published in The Epoch Times here.

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Canada’s New Border Bill Spies On You, Not The Bad Guys

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Lee Harding

Lee Harding warns that the federal government’s so-called border bill lets officials snoop on your data, ban big cash payments and even open your mail – all without a warrant

Think Bill C-2 is about stopping fentanyl? Think again. It lets the feds snoop your data, open your mail and ban big cash payments – no warrant needed

The federal government is using the pretext of border security, the fentanyl crisis and transnational crime to push through Bill C-2, legislation that dangerously expands surveillance powers, undermines Canadians’ privacy and restricts financial freedom. This so-called Strong Borders Act is less about protecting borders and more about policing citizens.

Bill C-2, a 130-page omnibus bill introduced on June 3, grants broad new powers to government agencies to spy on Canadians and share personal information with foreign countries. A more honest title might be the Snoop and Gossip Act.

Among its most intrusive provisions, the bill would make it illegal for any business, profession or charity to accept cash payments over $10,000, even if made in smaller, related transactions. Want to pay a contractor $10,001 in five separate payments for home renovations? Too bad.

The Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms quickly condemned the move. “Restricting the use of cash is a dangerous step toward tyranny and totalitarianism,” the organization posted to X. “Cash gives citizens privacy, autonomy, and freedom from surveillance by government and by banks.”

Under Bill C-2, internet service providers could be compelled—under threat of fines—to hand over names, locations and “pseudonyms” of users without a warrant. Any peace officer or public officer can demand this data by merely claiming “reasonable grounds to suspect” an offence “has been or will be committed.”

It doesn’t stop there. The bill would also authorize the government to open private mail under the same vague threshold of suspicion.

Experts in law and privacy say the bill is a massive overreach. University of Ottawa internet law scholar Michael Geist and Kate Robertson of the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab both point out that successive federal governments have sought to expand internet surveillance for years, but Bill C-2 goes further than ever before.

“Bill C-2’s big brother tactics combine expansive warrantless disclosure with unprecedented secrecy,” Geist warns. He adds that the bill “overreaches by including measures on internet subscriber data that have nothing to do with border safety or security but raise privacy and civil liberties concerns.”

If the intent were truly to combat fentanyl trafficking and transnational crime, better tools already exist. Conservative MP Frank Caputo pointed out that the bill has 16 parts but says nothing about increasing penalties or jail time for fentanyl traffickers.

“There is nothing about bail in the bill,” Caputo said during early debate on the bill. “In this omnibus bill, it says that offenders can serve their sentence for trafficking in fentanyl from their couch.”

Bloc Québécois MP Claude DeBellefeuille argued that strengthening border security requires more boots on the ground. Two rural border crossings in her riding recently had their staffed hours cut in half.

“It is estimated that the CBSA (Canada Border Services Agency) already has a shortage of between 2,000 and 3,000 border services officers for current duties. If they are given new responsibilities, however necessary, there will be an even greater shortage,” she said.

Not only does Bill C-2 contradict Supreme Court precedent. It also sets the stage for Canada to share sensitive personal information with foreign governments. In 2014, the court ruled that Canadians have a “reasonable expectation of privacy in the subscriber information” provided to internet service providers and that police requests for such data amount to a “search” requiring a warrant.

Robertson warns that the bill not only defies this precedent but also enables Canada to share this dubiously acquired information with 49 other countries under the Second Additional Protocol to the Cybercrime Convention. Canada signed the agreement in 2023 but hasn’t ratified it. Bill C-2 would make that possible.

She calls the protocol’s weak human rights safeguards “a direct threat to existing protections under international human rights law.” Robertson co-authored a submission urging the Department of Justice to reject the 2AP and instead support data-sharing frameworks that are built on consistent rights protections across all signatories.

Further complicating matters, Canada is in negotiations with the United States over a data-sharing agreement under that country’s CLOUD Act. Canada’s willingness to comply may reflect lingering trade pressures from the Trump administration, pressures that could again push Canada to compromise its legal independence and citizens’ rights.

This bill should be scrapped or thoroughly revised. Canadians should not have to surrender their privacy and human rights to serve a global law enforcement agenda that disregards civil liberties. If the line between national security and authoritarianism is erased, the greatest threat to Canadians may no longer be drug traffickers—it may be their own government.

Lee Harding is a research fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

New Book Warns The Decline In Marriage Comes At A High Cost

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

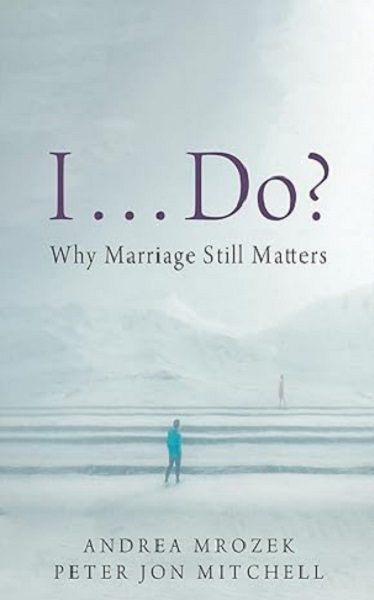

Travis Smith reviews I… Do? by Andrea Mrozek and Peter Jon Mitchell, showing that marriage is a public good, not just private choice, arguing culture, not politics, must lead any revival of this vital institution.

Andrea Mrozek and Peter Jon Mitchell, in I… Do?, write that the fading value of marriage is a threat to social stability

I… Do? by Andrea Mrozek and Peter Jon Mitchell manages to say something both obvious and radical: marriage matters. And not just for sentimental reasons. Marriage is a public good, the authors attest.

The book is a modestly sized but extensively researched work that compiles decades of social science data to make one central point: stable marriages improve individual and societal well-being. Married people are generally healthier, wealthier and more resilient. Children from married-parent homes do better across almost every major indicator: academic success, mental health, future earnings and reduced contact with the justice system.

The authors refer to this consistent pattern as the “marriage advantage.” It’s not simply about income. Even in low-income households, children raised by married parents tend to outperform their peers from single-parent families. Mrozek and Mitchell make the case that marriage functions as a stabilizing institution, producing better outcomes not just for couples and kids but for communities and, by extension, the country.

While the book compiles an impressive array of empirical findings, it is clear the authors know that data alone can’t fix what’s broken. There’s a quiet but important concession in these pages: if statistics alone could persuade people to value marriage, we would already be seeing a turnaround.

Marriage in Canada is in sharp decline. Fewer people are getting married, the average age of first marriage continues to climb, and fertility rates are hitting historic lows. The cultural narrative has shifted. Marriage is seen less as a cornerstone of adult life and more as a personal lifestyle choice, often put off indefinitely while people wait to feel ready, build their careers or find emotional stability.

The real value of I… Do? lies in its recognition that the solutions are not primarily political. Policy changes might help stop making things worse, but politicians are not going to rescue marriage. In fact, asking them to may be counterproductive. Looking to politicians to save marriage would involve misunderstanding both marriage and politics. Mrozek and Mitchell suggest the best the state can do is remove disincentives, such as tax policies and benefit structures that inadvertently penalize marriage, and otherwise get out of the way.

The liberal tradition once understood that family should be considered prior to politics for good reason. Love is higher than justice, and the relationships based in it should be kept safely outside the grasp of bureaucrats, ideologues, and power-seekers. The more marriage has been politicized over recent decades, the more it has been reshaped in ways that promote dependency on the impersonal and depersonalizing benefactions of the state.

The book takes a brief detour into the politics of same-sex marriage. Mrozek laments that the topic has become politically untouchable. I would argue that revisiting that battle is neither advisable nor desirable. By now, most Canadians likely know same-sex couples whose marriages demonstrate the same qualities and advantages the authors otherwise praise.

Where I… Do? really shines is in its final section. After pages of statistics, the authors turn to something far more powerful: culture. They explore how civil society—including faith communities, neighbourhoods, voluntary associations and the arts can help revive a vision of marriage that is compelling, accessible and rooted in human experience. They point to storytelling, mentorship and personal witness as ways to rebuild a marriage culture from the ground up.

It’s here that the book moves from description to inspiration. Mrozek and Mitchell acknowledge the limits of top-down efforts and instead offer the beginnings of a grassroots roadmap. Their suggestions are tentative but important: showcase healthy marriages, celebrate commitment and encourage institutions to support rather than undermine families.

This is not a utopian manifesto. It’s a realistic, often sobering look at how far marriage has fallen off the public radar and what it might take to put it back. In a political climate where even mentioning marriage as a public good can raise eyebrows, I… Do? attempts to reframe the conversation.

To be clear, this is not a book for policy wonks or ideologues. It’s for parents, educators, community leaders and anyone concerned about social cohesion. It’s for Gen Xers wondering if their children will ever give them grandchildren. It’s for Gen Zers wondering if marriage is still worth it. And it’s for those in between, hoping to build something lasting in a culture that too often encourages the opposite.

If your experiences already tell you that strong, healthy marriages are among the greatest of human goods, I… Do? will affirm what you know. If you’re skeptical, it won’t convert you overnight, but it might spark a much-needed conversation.

Travis D. Smith is an associate professor of political science at Concordia University in Montreal. This book review was submitted by the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

-

illegal immigration2 days ago

illegal immigration2 days agoICE raids California pot farm, uncovers illegal aliens and child labor

-

Uncategorized14 hours ago

Uncategorized14 hours agoCNN’s Shock Climate Polling Data Reinforces Trump’s Energy Agenda

-

Opinion6 hours ago

Opinion6 hours agoPreston Manning: Three Wise Men from the East, Again

-

Addictions6 hours ago

Addictions6 hours agoWhy B.C.’s new witnessed dosing guidelines are built to fail

-

Business4 hours ago

Business4 hours agoCarney Liberals quietly award Pfizer, Moderna nearly $400 million for new COVID shot contracts

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoTrump to impose 30% tariff on EU, Mexico

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoLNG Export Marks Beginning Of Canadian Energy Independence

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney government should apply lessons from 1990s in spending review