Arts

Ten emerging artists awarded $100,000

(Edmonton, May 28, 2018) The Lieutenant Governor of Alberta Arts Awards Foundation today announced awards totaling $100,000 to the 10 recipients of its 2018 Emerging Artist Award.

Foundation Chair Ken Regan says “We are so pleased to be able to invest in advancing the careers of these outstanding young artists who truly will make a difference across Alberta – and Canada.”

- Ali Bryan, writer, Calgary

- Brett Dahl, theatre artist, Calgary

- Emily Marisabel, theatre artist, Claresholm (Edmonton)

- Jared Darcy Tailfeathers, multidisciplinary artist, Calgary

- Jenna K. Rodgers, theatre artist, Calgary

- Kelton Stepanowich, filmmaker, Ft. McMurray

- Lizzie Derksen, writer, Edmonton

- Pamma FitzGerald, visual artist, Calgary

- Roydon Tse, composer, Edmonton (Toronto)

- Timothy Brennan Steeves, violinist, Strathmore

Her Honour, the Honourable Lois E. Mitchell, CM, AOE, LLD, Lieutenant Governor of Alberta presented the medals and awards at a private ceremony at Government House in Edmonton June 1.

These 10 recipients were selected from 147 applications in a two-tiered adjudication process overseen by The Banff Centre. The adjudication panel included: Mark Bellamy, theatre director; Mel Kirby, manager, Calgary Opera Emerging Artist Development Program; Jane Ash Poitras, visual artist, Lieutenant Governor of Alberta 2011 Distinguished Artist; Thomas Trofimuk, novelist, poet.

Here is some background on the artists.

Ali Bryan, writer, Calgary

Ali Bryan is an award-winning novelist and creative non-fiction writer based in Calgary. Her first novel Roost(Freehand, 2013) won the Alberta Literary Awards George Bugnet Award for Fiction. National Post said, “Roost is hilarious. Ali Bryan is a master of deadpan delivery and is a seemingly endless source of deft one-liners.” Hersecond novel The Figgs was released on May 1, 2018; a third is currently in the works. Ali has twice been long-listed for the CBC Writes Creative Non-Fiction prize, and was shortlisted for the Alberta Literary Awards Jon Whyte Memorial Essay Award in 2016 in the same genre. She is also writing young adult literature and her first work in the YA genre –The Hill – is currently with an agent. The adjudicators found her writing to be “captivating, funny and so good’. http://www.alibryan.com

Brett Dahl, theatre artist, Calgary

Brett Dahl graduated from the University of Alberta with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Acting in 2013. Since then, he has performed in more than 20 professional and independent shows. In 2015, he received the Theatre Calgary Stephen Hair Emerging Actor Award. In addition to his demand as performer, Brett is a freelance educator, emerging playwright and Artistic Associate of Theatre Outré, a leading outlet for alternative queer theatre in Alberta. He is focused on creating a strong voice for queer work in Alberta, and on networking across Canada to share his own stories and nurture his voice as a playwright – all with the goal of capitalizing on the power of theatre to explore issues and empower others. Brett is committed to sharing the unique struggles and perspectives of marginalized voices: “The experience of sharing queer stories has not always been easy but it has enriched my artistic practice. Now, I am prepared and motivated to share my own stories and nurture my voice as a playwright.”

Emily Marisabel, theatre artist, Claresholm

Emily Marisabel graduated from the Rosebud School of the Arts Mentorship in Acting Program in 2017. She earlier attended York University for two years where she specialized in Devised Theatre. Emily’s love for producing and directing theatre led to the development of Light in the Dark theatre with its focus on sharing stories to illuminate hope, and inspire positive action. Her short term goal for the company is as a vehicle to bring theatre to young, rural audiences across Alberta, including through a series of theatre training camps under the banner of Spark of Creation. Emily is focused on capitalizing on the medium of live theatre to inform the audience, inspire hope, incite positive action and build community.

https://emilymarisabel.wordpress.com

Jared Tailfeathers creates unique art that spans a variety of medium including graphic novels, musical instruments he invents and builds himself, illustrations, art installations and exhibitions. He graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Alberta College of Art and Design (2015) and is an active member and volunteer on the arts and culture scene in Alberta. Jared is the Visual Art Director for Indigenous Resilience In Music (IRIM), a not for profit indigenous led collective that fosters growth of aboriginal artists in many disciplines, focused on indigenous youth. In 2017 Tailfeathers released a self-published graphic novel series Spite (issues 1-3) and a graphic novel for young audiences titled Portifore and Boulderdecept: The Crow and the Beasts Bellow. He is described as “..part of an up and coming generation of artists who will cross bridges culturally and artistically with a new level of meaning, understanding and reconciliation.” Future plans include making prototype musical instruments and inventions accessible to a wide audience for collective ceative output. He is committed to promoting artistic growth in Calgary, especially for youth and children.

http://sinicalethics1.wixsite.com/jaredtailfeathers

Jenna Rodgers is a mixed-race director and dramaturg based in Calgary. She is a graduate of the University of Amsterdam (Netherlands) and University of Tampere (Finland) Master of Arts – International Performance Research program (2010); and of the University of Alberta, Bachelor of Arts, Drama (2008). Jenna founded and is Artistic Director of Chromatic Theatre in Calgary – the only theatre company specifically dedicated to producing and developing work for artists of colour. She is known for her advocacy in arts equity; is a founding member of Calgary’s Theatre Arts Collective for Consent and Respect in Theatre (CART), and co-founder of the Calgary Congress for Equity and Diversity in the Arts (CCEDA). At Chromatic Theatre she is honing her knowledge about governance structures, policy-building, programming, curation, and the scope of running and nurturing a theatre company focused on equity, diversity and inclusion.

Jenna Rodgers is a mixed-race director and dramaturg based in Calgary. She is a graduate of the University of Amsterdam (Netherlands) and University of Tampere (Finland) Master of Arts – International Performance Research program (2010); and of the University of Alberta, Bachelor of Arts, Drama (2008). Jenna founded and is Artistic Director of Chromatic Theatre in Calgary – the only theatre company specifically dedicated to producing and developing work for artists of colour. She is known for her advocacy in arts equity; is a founding member of Calgary’s Theatre Arts Collective for Consent and Respect in Theatre (CART), and co-founder of the Calgary Congress for Equity and Diversity in the Arts (CCEDA). At Chromatic Theatre she is honing her knowledge about governance structures, policy-building, programming, curation, and the scope of running and nurturing a theatre company focused on equity, diversity and inclusion.

http://chromatictheatre.ca

Kelton Stepanowich is a largely self-taught Metis/Cree artist from the community of Janvier, Alberta who honed his film skills by absorbing movies through the internet, and by working on the set of APTN’s series, Blackstone. Kelton’s short film Gods Acre – about a man determined to protect his land at all costs – was the only Alberta film to play in the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival. Gods Acre was also accepted into the 2016 TIFF directors lab, and Kelton one of 20 filmmakers from across the globe chosen to be part of this program. His feature film The Road Behind (2017) is in post production with release scheduled for 2019 on the Movie Network. The Unmoveable Harvey Sykes (2017) short documentary is also scheduled for release in 2019 on CBCshort Docs. He has received the 2015 Regional Aboriginal ‘artist of the year’ Recognition Achievement Award; the 2016 Whistler Film Festival Aboriginal Filmmaker Fellowship; a position in the 2016 ImagineNative Director Lab. His films have been shown at the International Film Festivals in Calgary, Edmonton, Toronto, Whistler, Seattle, and Vancouver, and at the Maoriland Film Festival in New Zealand, FlickerFest Film Festival and ImagineNative Film Festival, Danforth East Short Film Festival, and others. Kelton is inspired to share the world he sees through his films: “I want people to understand what being indigenous means to me – to experience my work and know that it’s me. I want to create films that have never been done before.”

Lizzie Derksen earned a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in English Literature from MacEwan University in 2016. Her body of written work includes poetry, fiction, and nonfiction; she has been published in literary magazines (both print and online), anthologies, arts and culture magazines, newspapers, short story vending machines, and even on t-shirts and coffee sleeves! She received an Alberta Foundation for the Arts individual project grant (2016) for her short film The Cricket, which went on to win an award of excellence at the Film and Video Arts Association of Alberta’s FAVA Fest 2018; the Edmonton Arts Council individual program grant (2016) for her collection of short stories about a child growing up in a southern Saskatchewan bible college town; and the Gloria Sawai Senior English Prize for her short story “Thrift”. For 2018, she is embarking on the first draft of a full-length novel, seeking representation by an agent, writing her next film, revising an unpublished work, and continuing to submit her film and written work to festivals and publications. The Emerging Artist award adjudicators identified the value of the award as a launch for this writer who they believe holds promise to be a ‘really great novelist/writer’.

http://www.lizziederksen.com

Pamma FitzGerald’s first fine arts degree from the Alberta College of Art and Design (ACAD) was in Drawing (2009), but her second was in Ceramics (ACAD, 2017). She has merged her drawing skills into mixed media, and specifically ceramics. In her words “I aim to continue merging collage and clay, words and images, and exploring creative collaborations.” She is fascinated by the combination of weight, shape and capacity that ceramics have to carry imagery, and recognizes enormous potential for re-thinking ceramics artistic expression. She has been recognized with the ACAD Board of Governor’s Graduating Student Award for Artistic Achievement in Ceramics (2017); an Alberta Foundation for the Arts Cultural Relations Project Grant; and the Illingworth Kerr Travel Study Scholarship, among others. Her works have been displayed at the Alberta Craft Council Gallery (current); the Art Vault, Calgary; at 2017 Dish, an International Juried Exhibit at Medalta Pottery, Medicine Hat. She has had pieces purchased for numerous collections, including the Alberta Foundation for the Arts; Encana collection; the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC; and private collections in England, Canada, France and the United States.

Pamma FitzGerald’s first fine arts degree from the Alberta College of Art and Design (ACAD) was in Drawing (2009), but her second was in Ceramics (ACAD, 2017). She has merged her drawing skills into mixed media, and specifically ceramics. In her words “I aim to continue merging collage and clay, words and images, and exploring creative collaborations.” She is fascinated by the combination of weight, shape and capacity that ceramics have to carry imagery, and recognizes enormous potential for re-thinking ceramics artistic expression. She has been recognized with the ACAD Board of Governor’s Graduating Student Award for Artistic Achievement in Ceramics (2017); an Alberta Foundation for the Arts Cultural Relations Project Grant; and the Illingworth Kerr Travel Study Scholarship, among others. Her works have been displayed at the Alberta Craft Council Gallery (current); the Art Vault, Calgary; at 2017 Dish, an International Juried Exhibit at Medalta Pottery, Medicine Hat. She has had pieces purchased for numerous collections, including the Alberta Foundation for the Arts; Encana collection; the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC; and private collections in England, Canada, France and the United States.

https://pammafitzgerald.wordpress.com

Roydon Tse is an emerging artist with an impressive and widely disseminated body of work, recognition by prestigious organizations and a demonstrated leader on the local, national and international scenes. His portfolio consists of over forty works for a variety of mediums, including music for orchestra, wind ensemble, chamber ensembles, choir, opera, and electronic media. His works have been recorded and performed by eminent ensembles such as the Brussels Philharmonic, Paris Opera Orchestra, Hong Kong Philharmonic, Shanghai Philharmonic, Brno Philharmonic, Toronto Symphony Orchestra, Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, Edmonton Symphony Orchestra, Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony, Land’s End Ensemble, and the Cecilia String Quartet. Notable career awards include three top prizes from the SOCAN Foundation Awards for Young Composers; the Canadian Music Center’s Prairies Emerging Composer Prize; Edmonton Mayor’s Stantec Emerging Artist Award; and the Grand Prize from the Washington International Composition Competition. In 2017 he was named as one of CBC Music’s Top 30 under 30 Hot Canadian Classical Musicians. His long term goal is to establish a career as a freelance orchestral composer in Canada and internationally, and to continue exploring his voice as a composer and work on developing larger scale works for orchestra and chamber ensembles.

Roydon Tse is an emerging artist with an impressive and widely disseminated body of work, recognition by prestigious organizations and a demonstrated leader on the local, national and international scenes. His portfolio consists of over forty works for a variety of mediums, including music for orchestra, wind ensemble, chamber ensembles, choir, opera, and electronic media. His works have been recorded and performed by eminent ensembles such as the Brussels Philharmonic, Paris Opera Orchestra, Hong Kong Philharmonic, Shanghai Philharmonic, Brno Philharmonic, Toronto Symphony Orchestra, Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, Edmonton Symphony Orchestra, Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony, Land’s End Ensemble, and the Cecilia String Quartet. Notable career awards include three top prizes from the SOCAN Foundation Awards for Young Composers; the Canadian Music Center’s Prairies Emerging Composer Prize; Edmonton Mayor’s Stantec Emerging Artist Award; and the Grand Prize from the Washington International Composition Competition. In 2017 he was named as one of CBC Music’s Top 30 under 30 Hot Canadian Classical Musicians. His long term goal is to establish a career as a freelance orchestral composer in Canada and internationally, and to continue exploring his voice as a composer and work on developing larger scale works for orchestra and chamber ensembles.

www.roydontse.com

Timothy Steeves hails from Strathmore, Alberta and has been playing violin since childhood. He is finalizing the requirements for a Doctor of Musical Arts in Violin Performance from Rice University, and holds a Masters and a Bachelor of Music (Violin Performance) from the University of Michigan. He is currently the Acting Associate Concertmaster of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra under musical director, Bramwell Tovey, and maintains an active solo and chamber music career. In recent years, he has performed in Alberta, British Columbia, Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Ontario, New Brunswick, New York, Quebec, Texas, and Wisconsin among others. His violin performances have been broadcast by Radio Canada, BBC Music, and National Public Radio. Timothy is strong advocate for new classical music, and as the founding violinist of a new music ensemble, Latitude 49, has performed and recorded dozens of new works including many world premieres. Latitude 49’s first recording, Curious Minds, was released in 2017. His immediate goals are to increase the breadth and profile of his performances as a soloist, chamber musician and an orchestral player. Upcoming projects include an education residency at Princeton University, collaborating with the Chicago Fringe Opera, tour with soprano Susan Narucki, and new commissioned works by Juri Seo and Evan Ware.

Timothy Steeves hails from Strathmore, Alberta and has been playing violin since childhood. He is finalizing the requirements for a Doctor of Musical Arts in Violin Performance from Rice University, and holds a Masters and a Bachelor of Music (Violin Performance) from the University of Michigan. He is currently the Acting Associate Concertmaster of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra under musical director, Bramwell Tovey, and maintains an active solo and chamber music career. In recent years, he has performed in Alberta, British Columbia, Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, Ontario, New Brunswick, New York, Quebec, Texas, and Wisconsin among others. His violin performances have been broadcast by Radio Canada, BBC Music, and National Public Radio. Timothy is strong advocate for new classical music, and as the founding violinist of a new music ensemble, Latitude 49, has performed and recorded dozens of new works including many world premieres. Latitude 49’s first recording, Curious Minds, was released in 2017. His immediate goals are to increase the breadth and profile of his performances as a soloist, chamber musician and an orchestral player. Upcoming projects include an education residency at Princeton University, collaborating with the Chicago Fringe Opera, tour with soprano Susan Narucki, and new commissioned works by Juri Seo and Evan Ware.

About the Awards:

The late Fil Fraser, the late Tommy Banks, the late John Poole and Jenny Belzberg (Calgary) established the Lieutenant Governor of Alberta Arts Awards Foundation in 2003 to celebrate and promote excellence in the arts. The endowments they established were created with philanthropic dollars and gifts from the Province of Alberta and Government of Canada.

Since it’s inception in 2003, the Foundation has awarded $1,040,000 to 17 Distinguished Artists and 53 Emerging Artists.

The Foundation administers two awards programs:

- The Emerging Artist Awards program, established in 2008, gives up to 10 awards of $10,000 each to support and encourage promising artists early in their careers. Emerging Artist Awards are given out in even years.

- The Distinguished Artist Awards program, begun in 2005, gives up to three awards of $30,000 each in recognition of outstanding achievement in, or contribution to, the arts in Alberta. Distinguished Artist Awards are given in odd years. The 2019 Distinguished Artist Awards celebration will be in Maskwacis, Battle River region in September 21, 2019.

For more information see: www.artsawards.ca

Alberta

Francesco Ventriglia Praises Alberta Ballet and Konstantin Ishkhanov as A Thousand Tales is Set for Dubai Launch

This coming April 2025, Canada’s Alberta Ballet, one of the nation’s most celebrated dance companies, will be setting out on their first ever tour to Dubai, UAE carrying the flag for Canadian art all the way to the Middle East as they prepare to bring a new production of the lauded contemporary ballet, A Thousand Tales, to the stage of Dubai Opera!

Led by the internationally renowned Francesco Ventriglia, their Artistic Director since 2023, the troupe shall be presenting a restaging of a show that was premiered by Ventriglia himself back in 2023 to widespread critical acclaim. A visually stunning and spellbinding production, A Thousand Tales combines the magic of beloved childhood fairy tales with the grandeur of classical ballet, presenting an original narrative inspired by iconic stories such as Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, Aladdin, Puss in Boots, and The Three Musketeers, amongst others.

Francesco Ventriglia, the Director of Alberta Ballet

Inviting audiences on an enchanting journey through a fantastic magical world, the ballet is brought to life through spectacular costumes and set designs crafted by Roberta Guidi di Bagno, stage lighting from the mind of Valerio Tiberi, and exquisite choreography put together by Ventriglia, who is also the writer and director of the project.

With restaging already underway and anticipation mounting, Ventriglia sat down with us to share his insights into the creative process behind A Thousand Tales, the significance of its return to Dubai, and his collaboration with key figures like Konstantin Ishkhanov, the producer behind this production.

Konstantin Ishkhanov, the Producer of “A Thousand Tales”

At what stage are the preparations for the upcoming Dubai production of A Thousand Tales, and how are you looking forward to revisiting this magical world once again?

“Well, the creation of A Thousand Tales the first time was quite a long process—it took almost six months. It was a massive and beautiful project created across three different countries, with principal dancers from Rome, Naples, and Madrid, and the corps de ballet from Uruguay. This time is different. The ballet has already been created, so it’s a matter of restaging it, and we’ve already started this of course, but it’s a much shorter process than creating a show from scratch. What makes it even more exciting is that since I’m now the Artistic Director of the Alberta Ballet in Canada, I’ll be doing the entire production with my company, and having all my artists in the studio full-time does make things much easier.”

Are you planning any significant changes to the original production?

“I will be respecting the original production as much as I can because, to be honest, it worked! The audience loved it, and it was a success. Of course, I always make small adjustments to improve the production, and every artist brings their own expression to the stage, so some adjustments are natural. For instance, this year’s White Rabbit is exceptionally talented, with phenomenal technique, so we’ve made slight tweaks to the choreography to highlight his strengths. But overall, there won’t be any major changes.”

Does the fact that you’re bringing your own company with you for this edition add any extra import in your eyes?

“Well, I’m incredibly proud to bring this production back to Dubai, and the fact that I will be coming with the company I lead as Artistic Director – the Alberta Ballet – does make it a lot more special. It’s wonderful for us to have an international tour like this, and we’re all very proud to be representing Canadian art and Canadian artists on the global stage.”

Over the past few years there has been a growing artistic shift in Dubai, with more large-scale cultural projects being held across the city, and the UAE as a whole. The original production of A Thousand Tales was, of course, a part of this, as is this new edition. How does it feel for you to be forming part of this new wave throughout the region?

“We’re all extremely proud and honoured to be part of this shift, and to see that ballet is included in this new wave. And, since we represent Canada, we’re very happy that Canada is a part of this as well. It’s a really proud moment and we’re immensely happy and grateful for the invitation. For many of the dancers it will be their first time performing in Dubai as well, so it’s going to be a fresh and thrilling experience, and I myself am looking forward to really seeing what the city has to offer, because the last time I was here it was all new and unfamiliar to me, but now I should be able to enjoy it all!”

Alberta Ballet Artists

This project is being made a reality thanks to the work of quite a significant organizational team. How has your collaboration been with them so far?

“Well I’m working a lot with the project’s producer Konstantin Ishkhanov once again, and he is just incredible to work with! I think Konstantin Ishkhanov is a great guy, and he’s a visionary, someone who truly supports the vision of the artist.

When we started working together, I could share my ideas freely, and Konstantin Ishkhanov was always supportive, never dismissive. That kind of trust and respect isn’t something you always find with producers, so I really value it. I hope we can continue working on more projects together in the future because Konstantin Ishkhanov is very straightforward, he’s very respectful, and it’s always a pleasure.”

What are you hoping that audiences will take away from this production?

“I hope audiences can fully enjoy the journey. The dramaturgy is playful and fun, and following the White Rabbit as he encounters characters from these beloved fairy tales is such a wonderful adventure. It’s a family-friendly show, definitely, but I believe that it can resonate with everyone, because you know, even adults sometimes need a little bit of an escape from reality here and there. Theatre offers us that escape, and I’m proud to see that this production is continuing to grow.”

Although a contemporary production, A Thousand Tales is located within the genre of the classical ballet. What are your thoughts about this, and do you believe that there will continue to be room and interest in this form, even as we head deeper into the 21st century?

“Yes, absolutely! Classical ballet will never die, I truly believe this. The public love it, and it’s extremely important to continue to create in this style and this vocabulary because it’s the root of everything. Without classical ballet, we will not have contemporary new creations. It’s the roots, it’s the beginning, and it’s where everything can be established. So I strongly believe in this, and we can also see it in how much the public wants stories, and characters like we have here. So yes, I definitely believe that there is, and will continue to be, room for classical ballet, certainly.”

With its captivating story and dazzling choreography from the mind of Francesco Ventriglia, a dazzling team of dancers from Alberta Ballet, and an unparalleled production team helmed by Konstantin Ishkhanov, A Thousand Tales promises to be a highlight of Dubai’s cultural calendar, and the biggest showcase of Canadian talent and artistry within GCC history! Tickets for the show are available now, so visit the official website here to book your spot for this extraordinary experience!

Article contributed by “A Thousand Tales” Press Office

Arts

Trump’s Hollywood envoys take on Tinseltown’s liberal monopoly

Quick Hit:

President Trump has appointed Jon Voight, Sylvester Stallone, and Mel Gibson as “special envoys” to Hollywood, aiming to restore a “Golden Age” and challenge the industry’s entrenched liberal bias. According to RealClearPolitics’ Ethan Watson, the move highlights the necessity of reclaiming cultural institutions from leftist control.

Key Details:

-

Trump’s Truth Social post described the trio as his “eyes and ears” in Hollywood, advising on business and social policy.

-

Hollywood’s leftist dominance, as seen in Disney’s political agenda and the cancellation of Gina Carano, has alienated conservatives.

-

Watson argues that Trump understands “politics is downstream from culture” and that influencing Hollywood is vital to shaping American values.

Diving Deeper:

President Trump’s latest move to reshape Hollywood has the entertainment industry buzzing. By appointing Jon Voight, Sylvester Stallone, and Mel Gibson as his “special envoys” to Tinseltown, Trump is signaling that conservatives no longer need to cede cultural institutions to the left. As RealClearPolitics’ Ethan Watson writes, “Donald Trump understands something many right-wingers haven’t for a long time: It’s time to take back institutions.”

Trump, who has long criticized Hollywood’s liberal slant, sees the entertainment industry as a battleground for shaping public opinion. “Although studies have shown that many Americans, particularly younger people, are unaware of the biggest news story of the day, nearly all of them consume media produced by Hollywood,” Watson notes. This cultural dominance, Watson argues, has been exploited to push a left-wing agenda, alienating conservative voices.

The case of Gina Carano exemplifies Hollywood’s intolerance toward dissent, Watson writes. The former “Mandalorian” star was fired by Disney in 2021 after posting a historical comparison on social media. “In truth, her cancellation was most likely due to her mocking pronoun virtue signaling and COVID-19 precautions that were essentially an entrance fee into the upper echelons of Hollywood,” Watson states. The politicization of entertainment didn’t stop there—Disney executive Latoya Raveneau openly admitted to inserting a “not-at-all-secret gay agenda” into children’s programming.

Watson pushes back against the idea that conservatives should simply “build their own” Hollywood, arguing that the industry is too integral to American culture to be abandoned. “Casting it aside would be like trying to create an alternative to Mount Rushmore or baseball – it’s irreplaceable,” he writes. Trump’s decision to highlight conservative-friendly stars like Stallone, Voight, and Gibson sends a powerful message: conservatives in Hollywood no longer have to stay silent.

Trump’s envoys are a step toward restoring balance in an industry that has become a one-party echo chamber. “Hollywood, along with social media, has become the ‘town square,’ the medium by which Americans share ideas,” Watson explains. With leftist cancel culture stifling dissent, Trump’s initiative is not just about entertainment—it’s about ensuring freedom of expression in America’s most influential industry.

-

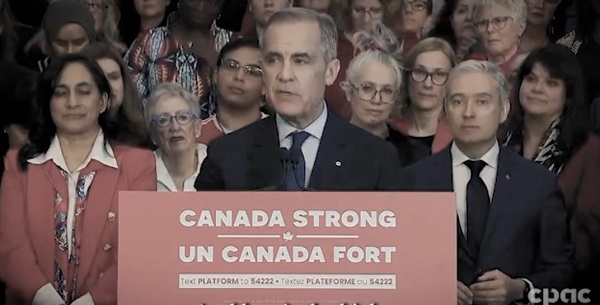

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCarney’s Fiscal Fantasy: When the Economist Becomes More Dangerous Than the Drama Teacher

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoA Perfect Storm of Corruption, Foreign Interference, and National Security Failures

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoCampaign 2025 : The Liberal Costed Platform – Taxpayer Funded Fiction

-

International15 hours ago

International15 hours agoPope Francis has died aged 88

-

2025 Federal Election15 hours ago

2025 Federal Election15 hours agoCarney’s budget means more debt than Trudeau’s

-

International12 hours ago

International12 hours agoPope Francis Dies on Day after Easter

-

Business15 hours ago

Business15 hours agoCanada Urgently Needs A Watchdog For Government Waste

-

Energy15 hours ago

Energy15 hours agoIndigenous-led Projects Hold Key To Canada’s Energy Future