Agriculture

Moisture situation in Alberta following warm and dry first half of winter

Agricultural Moisture Situation Update – January 3, 2024

Synopsis

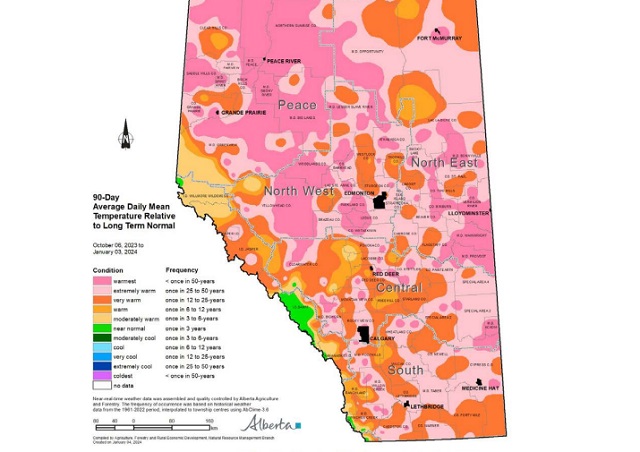

This year’s El Niño has developed into a strong El Niño and currently has a 54% chance of developing into a “historically strong” event, according to NOAA. Current forecasts are projecting El Niño to diminish in April 2024. In the past for Alberta, not all El Niño’s have resulted in warmer and drier weather; however, this unusually warm and dry winter will forever be tied to the 2023-2024 El Niño and will serve as an important data point in the future.

In the 90-days since October 6, 2023, temperatures have remained well above average, with many parts of the northern-half of the province seeing temperatures this warm less than once in 50 years (Map 1). This coupled with low precipitation accumulations has resulted in virtually snow free

conditions across parts of all four of our agricultural regions

(Map 2).

Winter Precipitation Accumulations

November 1, 2023 to January 3, 2024

Since November 1st, the unofficial start to winter in Alberta, precipitation has been well below average across much of Alberta’s agricultural areas (Map 3).

Most of the lands south of Grande Prairie and north of Ponoka are estimated to have a winter thus far, this dry on average, less than once in 50-years. Dry conditions have also persisted across the Central and Southern Regions, ranging from a few widely scattered pockets of near normal to at least once in 25 year lows, centered around the Jenner area (approx. 200 km east of Calgary). Total accumulations currently range from less than 3 mm through parts of the North West and North East Regions up to only 20-30 mm along the foothills and through the western and northern portions of the Peace Region (Map 4).

For the dryer parts of the North West and North East Regions this translates to less than 10% of the 1991-2020 average (Map 5).

Elsewhere, most other lands have received precipitation accumulations that have generally been less

than 50% of the 1991-2020 average.

Perspective

From an annual moisture budget perspective, October through to March generally mark the dry season across the agricultural areas (Map 6), accounting for only about 20% of average annual accumulations across most of the Southern Region, to upwards of 30-35% across the Peace Region.

These significant moisture deficits thus far (50% of the way through the dry season), while discouraging to many, make up only a small portion of the annual moisture budget for an area. Winter is not over yet and if the current forecast is correct, a significant cold snap is on its way over the next few days and it is expected to persist well into next week, perhaps even longer. Along with the cold snap, there is also a forecast for moisture and the promise of at least some snow cover across many areas.

Spring is yet many weeks away and anything can happen between now and then. Furthermore, February on average, is the driest month of the year with most agricultural lands normally receiving less than 15 mm of moisture during this month (Map 6). Let’s hope, for the sake of our producers,

that we descend into at least near “normal” winter conditions and that we see one of Alberta’s famous weather reversals, with respect to moisture. Above average snow fall is very much needed now. Much of the land is extremely dry and has been held tenaciously in the grip of a long-lasting dry

cycle that needs to end soon!

Agriculture

Growing Alberta’s fresh food future

A new program funded by the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership will accelerate expansion in Alberta greenhouses and vertical farms.

Albertans want to keep their hard-earned money in the province and support producers by choosing locally grown, high-quality produce. The new three-year, $10-milllion Growing Greenhouses program aims to stimulate industry growth and provide fresh fruit and vegetables to Albertans throughout the year.

“Everything our ministry does is about ensuring Albertans have secure access to safe, high-quality food. We are continually working to build resilience and sustainability into our food production systems, increase opportunities for producers and processors, create jobs and feed Albertans. This new program will fund technologies that increase food production and improve energy efficiency.”

“Through this investment, we’re supporting Alberta’s growers and ensuring Canadians have access to fresh, locally-grown fruits and vegetables on grocery shelves year-round. This program strengthens local communities, drives innovation, and creates new opportunities for agricultural entrepreneurs, reinforcing Canada’s food system and economy.”

The Growing Greenhouses program supports the controlled environment agriculture sector with new construction or expansion improvements to existing greenhouses and vertical farms that produce food at a commercial scale. It also aligns with Alberta’s Buy Local initiative launched this year as consumers will be able to purchase more local produce all year-round.

The program was created in alignment with the needs identified by the greenhouse sector, with a goal to reduce seasonal import reliance entering fall, which increases fruit and vegetable prices.

“This program is a game-changer for Alberta’s greenhouse sector. By investing in expansion and innovation, we can grow more fresh produce year-round, reduce reliance on imports, and strengthen food security for Albertans. Our growers are ready to meet the demand with sustainable, locally grown vegetables and fruits, and this support ensures we can do so while creating new jobs and opportunities in communities across the province. We are very grateful to the Governments of Canada and Alberta for this investment in our sector and for working collaboratively with us.”

Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership (Sustainable CAP)

Sustainable CAP is a five-year, $3.5-billion investment by federal, provincial and territorial governments to strengthen competitiveness, innovation and resiliency in Canada’s agriculture, agri-food and agri-based products sector. This includes $1 billion in federal programs and activities and $2.5 billion that is cost-shared 60 per cent federally and 40 per cent provincially/territorially for programs that are designed and delivered by provinces and territories.

Quick facts

- Alberta’s greenhouse sector ranks fourth in Canada:

- 195 greenhouses produce $145 million in produce and 60 per cent of them operate year-round.

- Greenhouse food production is growing by 6.2 per cent annually.

- Alberta imports $349 million in fresh produce annually.

- The program supports sector growth by investing in renewable and efficient energy systems, advanced lighting systems, energy-saving construction, and automation and robotics systems.

Related information

Agriculture

Canada’s air quality among the best in the world

From the Fraser Institute

By Annika Segelhorst and Elmira Aliakbari

Canadians care about the environment and breathing clean air. In 2023, the share of Canadians concerned about the state of outdoor air quality was 7 in 10, according to survey results from Abacus Data. Yet Canada outperforms most comparable high-income countries on air quality, suggesting a gap between public perception and empirical reality. Overall, Canada ranks 8th for air quality among 31 high-income countries, according to our recent study published by the Fraser Institute.

A key determinant of air quality is the presence of tiny solid particles and liquid droplets floating in the air, known as particulates. The smallest of these particles, known as fine particulate matter, are especially hazardous, as they can penetrate deep into a person’s lungs, enter the blood stream and harm our health.

Exposure to fine particulate matter stems from both natural and human sources. Natural events such as wildfires, dust storms and volcanic eruptions can release particles into the air that can travel thousands of kilometres. Other sources of particulate pollution originate from human activities such as the combustion of fossil fuels in automobiles and during industrial processes.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) publish air quality guidelines related to health, which we used to measure and rank 31 high-income countries on air quality.

Using data from 2022 (the latest year of consistently available data), our study assessed air quality based on three measures related to particulate pollution: (1) average exposure, (2) share of the population at risk, and (3) estimated health impacts.

The first measure, average exposure, reflects the average level of outdoor particle pollution people are exposed to over a year. Among 31 high-income countries, Canadians had the 5th-lowest average exposure to particulate pollution.

Next, the study considered the proportion of each country’s population that experienced an annual average level of fine particle pollution greater than the WHO’s air quality guideline. Only 2 per cent of Canadians were exposed to fine particle pollution levels exceeding the WHO guideline for annual exposure, ranking 9th of 31 countries. In other words, 98 per cent of Canadians were not exposed to fine particulate pollution levels exceeding health guidelines.

Finally, the study reviewed estimates of illness and mortality associated with fine particle pollution in each country. Canada had the fifth-lowest estimated death and illness burden due to fine particle pollution.

Taken together, the results show that Canada stands out as a global leader on clean air, ranking 8th overall for air quality among high-income countries.

Canada’s record underscores both the progress made in achieving cleaner air and the quality of life our clean air supports.

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoParis Climate Deal Now Decade-Old Disaster

-

armed forces2 days ago

armed forces2 days agoOttawa’s Newly Released Defence Plan Crosses a Dangerous Line

-

Censorship Industrial Complex21 hours ago

Censorship Industrial Complex21 hours agoHow Wikipedia Got Captured: Leftist Editors & Foreign Influence On Internet’s Biggest Source of Info

-

Indigenous1 day ago

Indigenous1 day agoResidential school burials controversy continues to fuel wave of church arsons, new data suggests

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta’s huge oil sands reserves dwarf U.S. shale

-

Business24 hours ago

Business24 hours agoOttawa Pretends To Pivot But Keeps Spending Like Trudeau

-

Energy23 hours ago

Energy23 hours agoLiberals Twisted Themselves Into Pretzels Over Their Own Pipeline MOU

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCanada’s New Green Deal