Uncategorized

Sickness, fear, harassment in Mexico whittle away at caravan

HUIXTLA, Mexico — Little by little, sickness, fear and police harassment are whittling down the migrant caravan making its way to the U.S. border, with many of the 4,000 to 5,000 migrants camped overnight under plastic sheeting in a town in southern Mexico complaining of exhaustion.

The group, many with children and even pushing toddlers in strollers, planned to depart Mapastepec at dawn Thursday with more than 1,000 miles still to go before they reach the U.S. border.

But in recent days a few hundred have accepted government offers to bus them back to their home countries.

Jose David Sarmientos Aguilar, a 16-year-old student from San Pedro Sula, Honduras, was one of at least 80 migrants waiting in the town square of Huixtla, where the rest of the caravan departed Wednesday morning, for four buses that would take them back to Honduras.

Sarmientos Aguilar said it was partly the spontaneous nature of the caravan — many people joined on the spur of the moment — as well as the

He joined the march “without thinking about what could happen and the consequences it could bring,” he said. He said the death of a migrant who fell off a truck Monday — and vague

“There have been a lot of tragedies. It’s not necessary to go on losing more lives to reach there (the U.S.),” he said. “I am a little sick in the chest. I have a cough. And so instead of risking getter sicker and something happening to me, it’s better to go home.”

Carlos Roberto Hernandez, of Yoro province in Honduras, has a rumbling cough. For him, it was the scorching heat during the day and the evening rains that led him to drop out.

“We got hit by rain, and ever since then I’ve had a cold,” Hernandez said. Asked if he would make another attempt to reach the U.S., he said emphatically: “No. I’m going to make my life in Honduras.”

For Pedro Arturo Torres, it appeared to be homesickness that broke his determination to reach the U.S.

“We didn’t know what lay ahead,” said Torres. “We want to return to our country, where you can get by — even if just with beans, but you can survive, there with our families, at peace.”

The Mexican federal government’s attitude has also played a role in wearing down the caravan.

All the food, old clothes, water and medicine given to the migrants have come from private citizens, church groups or sympathetic local officials.

The federal government hasn’t given the migrants on the road a single meal, a bathroom or a bottle of water. It has reserved those basic considerations only for migrants who turn themselves in at immigration offices to apply for visas or be deported. Officials say nearly 1,700 migrants have already dropped out and applied for asylum in Mexico.

Sometimes federal police have interfered with the caravan.

In at least one instance, The Associated Press saw federal police officers force a half-dozen passenger vans to pull over and make the drivers kick migrants off, while leaving Mexican passengers aboard. In a climate where heat makes walking nearly impossible at midday, such tactics may eventually take a toll on migrants’ health.

In Mapastepec, where the main group stayed Wednesday night, it appeared the size of the caravan had diminished slightly. The United Nations estimated earlier in the week that about 7,000 people were in the group. The Mexican government gave its own figure Wednesday of “approximately 3,630.”

Parents say they keep going for their children’s futures, and fears of what could happen to them back home in gang-dominated Honduras, which was the main motivation for deciding to leave in the first place.

“They can’t be alone. … There’s always danger,” said Ludin Giron, a Honduran street vendor making the difficult journey with her three young children. “When (gang members) see a pretty girl, they want her for themselves. If they see a boy, they want to get him into drugs.”

Refusing either demand can be deadly. Honduras has a homicide rate of about 43 per 100,000 inhabitants, one of the highest in the world for any country not in open war.

On Wednesday, Giron crammed with her children, 3-year-olds Justin and Nicole and 5-year-old Astrid, into the seat of a motorcycle taxi meant for only two passengers. Also perched on the perilously overcrowded motorbike were Reyna Esperanza Espinosa and her 11-year-old daughter, Elsa Araceli.

Espinosa, a tortilla maker from Cortes, Honduras, said there was no work back home. “That’s why we decided to come here, to give a better future for our children,” she said.

Such caravans have taken place regularly, if on a smaller scale, over the years, but U.S. President Donald Trump has seized on the phenomenon this year and made it a rallying call for his Republican base ahead of the Nov. 6 midterm elections.

Trump has blamed Democrats for what he says are weak immigration laws, and he claimed that MS-13 gang members and unknown “Middle Easterners” were hiding among the migrants. He later acknowledged there was “no proof” of the claim Middle Easterners were in the crowd. But he tweeted Wednesday that the U.S. “will never accept people coming into our Country illegally!”

Associated Press journalists

Another, smaller caravan earlier this year dwindled greatly as it passed through Mexico, with only about 200 making it to the California border. Those who do make it into the U.S. face a hard time being allowed to stay. U.S. authorities do not consider poverty, which many cite as a reason for migrating, in processing asylum applications.

Carmen Mejia from Copan, Honduras, carried 3-year-old Britany Sofia Alvarado in her arms, and clutched the hand of 7-year-old Miralia Alejandra Alvarado, also sweaty — and feverish.

Mejia said she was worn out. Still, she pledged to go on. “I’ve walked a long way. I don’t want to return. I want a better future for my children.”

Mark Stevenson, The Associated Press

Uncategorized

CNN’s Shock Climate Polling Data Reinforces Trump’s Energy Agenda

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

As the Trump administration and Republican-controlled Congress move aggressively to roll back the climate alarm-driven energy policies of the Biden presidency, proponents of climate change theory have ramped up their scare tactics in hopes of shifting public opinion in their favor.

But CNN’s energetic polling analyst, the irrepressible Harry Enten, says those tactics aren’t working. Indeed, Enten points out the climate alarm messaging which has permeated every nook and cranny of American society for at least 25 years now has failed to move the public opinion needle even a smidgen since 2000.

Appearing on the cable channel’s “CNN News Central” program with host John Berman Thursday, Enten cited polling data showing that just 40% of U.S. citizens are “afraid” of climate change. That is the same percentage who gave a similar answer in 2000.

Dear Readers:

As a nonprofit, we are dependent on the generosity of our readers.

Please consider making a small donation of any amount here.

Thank you!

Enten’s own report is an example of this fealty. Saying the findings “kind of boggles the mind,” Enten emphasized the fact that, despite all the media hysteria that takes place in the wake of any weather disaster or wildfire, an even lower percentage of Americans are concerned such events might impact them personally.

“In 2006, it was 38%,” Enten says of the percentage who are even “sometimes worried” about being hit by a natural disaster, and adds, “Look at where we are now in 2025. It’s 32%, 38% to 32%. The number’s actually gone down.”

In terms of all adults who worry that a major disaster might hit their own hometown, Enten notes that just 17% admit to such a concern. Even among Democrats, whose party has been the major proponent of climate alarm theory in the U.S., the percentage is a paltry 27%.

While Enten and Berman both appear to be shocked by these findings, they really aren’t surprising. Enten himself notes that climate concerns have never been a driving issue in electoral politics in his conclusion, when Berman points out, “People might think it’s an issue, but clearly not a driving issue when people go to the polls.”

“That’s exactly right,” Enten says, adding, “They may worry about in the abstract, but when it comes to their own lives, they don’t worry.”

This reality of public opinion is a major reason why President Donald Trump and his key cabinet officials have felt free to mount their aggressive push to end any remaining notion that a government-subsidized ‘energy transition’ from oil, gas, and coal to renewables and electric vehicles is happening in the U.S. It is also a big reason why congressional Republicans included language in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act to phase out subsidies for those alternative energy technologies.

It is key to understand that the administration’s reprioritization of energy and climate policies goes well beyond just rolling back the Biden policies. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin is working on plans to revoke the 2010 endangerment finding related to greenhouse gases which served as the foundation for most of the Obama climate agenda as well.

If that plan can survive the inevitable court challenges, then Trump’s ambitions will only accelerate. Last year’s elimination of the Chevron Deference by the Supreme Court increases the chances of that happening. Ultimately, by the end of 2028, it will be almost as if the Obama and Biden presidencies never happened.

The reality here is that, with such a low percentage of voters expressing concerns about any of this, Trump and congressional Republicans will pay little or no political price for moving in this direction. Thus, unless the polls change radically, the policy direction will remain the same.

David Blackmon is an energy writer and consultant based in Texas. He spent 40 years in the oil and gas business, where he specialized in public policy and communications.

Uncategorized

Kananaskis G7 meeting the right setting for U.S. and Canada to reassert energy ties

Energy security, resilience and affordability have long been protected by a continentally integrated energy sector.

The G7 summit in Kananaskis, Alberta, offers a key platform to reassert how North American energy cooperation has made the U.S. and Canada stronger, according to a joint statement from The Heritage Foundation, the foremost American conservative think tank, and MEI, a pan-Canadian research and educational policy organization.

“Energy cooperation between Canada, Mexico and the United States is vital for the Western World’s energy security,” says Diana Furchtgott-Roth, director of the Center for Energy, Climate and Environment and the Herbert and Joyce Morgan Fellow at the Heritage Foundation, and one of America’s most prominent energy experts. “Both President Trump and Prime Minister Carney share energy as a key priority for their respective administrations.

She added, “The G7 should embrace energy abundance by cooperating and committing to a rapid expansion of energy infrastructure. Members should commit to streamlined permitting, including a one-stop shop permitting and environmental review process, to unleash the capital investment necessary to make energy abundance a reality.”

North America’s energy industry is continentally integrated, benefitting from a blend of U.S. light crude oil and Mexican and Canadian heavy crude oil that keeps the continent’s refineries running smoothly.

Each day, Canada exports 2.8 million barrels of oil to the United States.

These get refined into gasoline, diesel and other higher value-added products that furnish the U.S. market with reliable and affordable energy, as well as exported to other countries, including some 780,000 barrels per day of finished products that get exported to Canada and 1.08 million barrels per day to Mexico.

A similar situation occurs with natural gas, where Canada ships 8.7 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day to the United States through a continental network of pipelines.

This gets consumed by U.S. households, as well as transformed into liquefied natural gas products, of which the United States exports 11.5 billion cubic feet per day, mostly from ports in Louisiana, Texas and Maryland.

“The abundance and complementarity of Canada and the United States’ energy resources have made both nations more prosperous and more secure in their supply,” says Daniel Dufort, president and CEO of the MEI. “Both countries stand to reduce dependence on Chinese and Russian energy by expanding their pipeline networks – the United States to the East and Canada to the West – to supply their European and Asian allies in an increasingly turbulent world.”

Under this scenario, Europe would buy more high-value light oil from the U.S., whose domestic needs would be back-stopped by lower-priced heavy oil imports from Canada, whereas Asia would consume more LNG from Canada, diminishing China and Russia’s economic and strategic leverage over it.

* * *

The MEI is an independent public policy think tank with offices in Montreal, Ottawa, and Calgary. Through its publications, media appearances, and advisory services to policymakers, the MEI stimulates public policy debate and reforms based on sound economics and entrepreneurship.

As the nation’s largest, most broadly supported conservative research and educational institution, The Heritage Foundation has been leading the American conservative movement since our founding in 1973. The Heritage Foundation reaches more than 10 million members, advocates, and concerned Americans every day with information on critical issues facing America.

-

espionage2 days ago

espionage2 days agoInside Xi’s Fifth Column: How Beijing Uses Gangsters to Wage Political Warfare in Taiwan — and the West

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoDecision expected soon in case that challenges Alberta’s “safe spaces” law

-

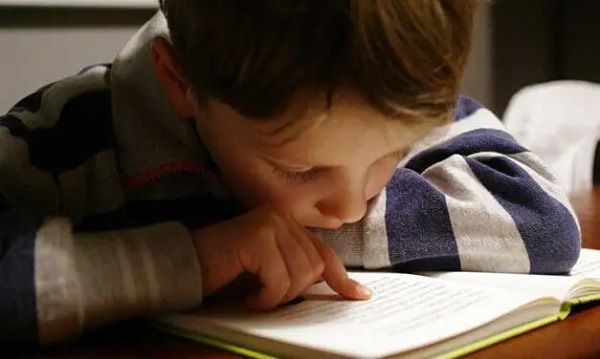

Education2 days ago

Education2 days agoOur kids are struggling to read. Phonics is the easy fix

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoBrazil sentences former President Bolsonaro to 27 years behind bars

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoWhy FDA Was Right To Say No To COVID-19 Vaccines For Healthy Kids

-

Business7 hours ago

Business7 hours agoCarney Admits Deficit Will Top $61.9 Billion, Unveils New Housing Bureaucracy

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoTrump Admin Torpedoing Biden’s Oil And Gas Crackdown

-

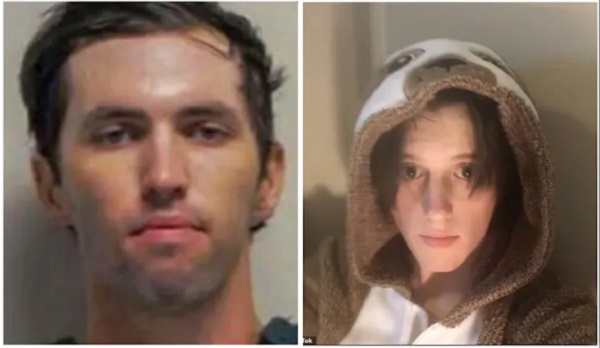

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day agoTransgender Roomate of Alleged Charlie Kirk Assassin Cooperating with Investigation