Health

RFK Jr. Shuts Down Measles Scare in His First Network Interview as HHS Secretary

The Vigilant Fox

The Vigilant Fox

CBS’s Jon LaPook tried to hype the measles panic, but Kennedy calmly dismantled the narrative and set the record straight.

The following is a streamlined and editorialized version of a thread that originally appeared on the American Values X page. It was edited and republished with permission. Click here to read the original thread.

HHS Secretary RFK Jr. recently set the record straight in an interview with CBS News’ chief medical correspondent, Dr. Jon LaPook. He pushed back on the claim that a second child had died from measles, exposing the narrative as not just misleading, but flat-out false.

But before that happened, Kennedy addressed the current measles outbreak and ongoing concerns about vaccine safety. He revealed that new safety trials are finally in motion.

“We don’t know the risks of many of these products,” he said. “They’re not adequately safety-tested.” He explained that “many of the vaccines are tested for only 3-4 days with NO placebo group.”

Kennedy made it clear this isn’t about banning vaccines—it’s about transparency. “I’ve always said … I’m not gonna take people’s vaccines away from them,” he said. “I’m gonna make sure that we have good science so that people can make an informed choice.” He added, “We are doing that science today.”

Kennedy was asked about Daisy Hildebrand, the young girl in Texas whose funeral he attended. Her death had been cited in headlines as proof of a growing measles crisis.

“It was very nice to be able to meet the parents in person and spend the whole day with them and share their lives with them and get to know their community,” he said. “The community was very welcoming and loving towards me.”

Kennedy described the experience warmly: “The Mennonite community was beautiful to me.” He added, “I went to a large lunch with the whole community and you had boys and girls sitting together and nobody was on a cell phone.”

That’s when Kennedy dropped the real bombshell: the child didn’t die from measles.

“The child whose funeral I attended this week was hospitalized three times from other illnesses,” he said. “She got measles and she got over the measles, according to her parents.” He added, “I saw the medical report on it today and the thing that killed her was not the measles, but it was a bacteriological infection.”

And it wasn’t the first time the media misled the public. Last month, another child’s death was falsely blamed on measles. But the truth is that it was a case of catastrophic medical error.

“Her death is the result of an egregious medical error,” CHD’s Mary Holland told Steve Bannon. “This girl wound up in the hospital because she did have some difficulty breathing, and instead of giving her breathing care, you’ll understand from the specialists with me that she got inaccurate, wrong-headed medical care, and that’s why she died.”

She added, “She did not die from measles. She died from a medical error, the third leading cause of death in this country.”

Thanks for reading. If you value the work being published here, upgrading your subscription is the most powerful way to support it. The more this Substack earns, the more we can expand the team, improve quality, and create the best reader experience possible.

For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

Health

Expert Medical Record Reviews Of The Two Girls In Texas Who Purportedly Died of Measles

I have long reviewed medical records of patients harmed by poor medical care. Here, I present clear evidence of what actually caused the 2 girls deaths in Texas. It wasn’t measles.

Before I start, I want all to know that the parents of both children are from the same community and know each other. They and the community are obviously in grief over these unnecessary and easily preventable deaths, which you will learn more about why below. I will state at the outset that, in my professional opinion, neither child died of measles. Not even close.

CASE #1 – Kaley Fehr, Age 6

I will only briefly discuss Kaley’s case because it was already covered extensively in an interview I did with CHD TV a little over two weeks ago. Plus, the record and findings are straightforward.

Kaley was a six-year-old previously healthy girl who contracted measles along with her four siblings (all of whom weathered the illness just fine under the care of Dr. Ben Edwards). As her rash was clearing, she began to develop signs and symptoms of “secondary bacterial pneumonia,” a not uncommon complication of almost any viral infection. To wit, one of my three daughters fell ill with the same after she contracted influenza at age 14; however, in her case, she recovered from it two days after receiving an appropriate antibiotic.

In Kaley’s case, her worsening respiratory status led her parents to bring her to Providence Covenant Children’s Hospital in Lubbock, Texas, on 2/22/25 at 12:08 PM.

The hospital correctly diagnosed her with secondary bacterial pneumonia and then treated her with two antibiotics, ceftriaxone and vancomycin. This was a blatant deviation from the standard of care in treating hospitalized patients with “community-acquired pneumonia (CAP),” the guidelines for which have long recommended a different combination, e.g., ceftriaxone and azithromycin (or a quinolone).

Only azithromycin and quinolones cover mycoplasma pneumonia, a prevalent cause of community-acquired pneumonia (this is why the guidelines recommend them). Neither ceftriaxone nor vancomycin will treat mycoplasma because they work by disrupting the cell walls of bacteria. Mycoplasma does not have a cell wall.

Vancomycin, the antibiotic they chose instead of azithromycin, is used to treat “hospital-acquired pneumonia” as it is one of the only antibiotics that covers MRSA (methicillin-resistant staph aureus). This common organism inhabits hospitals and medical facilities. Kaley was from a rural Mennonite community and had not been in any hospital.

Despite her persistent and increasing deterioration in respiratory status, which eventually led to requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation, this deviation from the standard of care went unnoticed and uncorrected until just over a day before she died, when the test for mycoplasma returned as “positive.”

Azithromycin was then immediately ordered. However, from the chart, it appears it took ten hours before she received her first dose (documentation of the exact time may be missing). She was dead less than 24 hours later, 4 days after being admitted. The time of death was 06:43 on 2/26/25. My opinion as to the cause of death is that it was from an overwhelming lung injury called Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) caused by mycoplasma pneumonia. The sole reason why she died from mycoplasma was because the initial antibiotic regimen violated the standard of care in the treatment of hospitalized community-acquired pneumonia because they neglected to treat her upon admission with azithromycin (i.e., a “Z-Pak deficiency”).

Note that azithromycin has excellent penetration into lung tissues and is highly effective at treating mycoplasma. Again, had they started azithromycin on Day 1, as has been recommended for decades, she would still be alive today.

The above findings were articulated in my interview with CHD TV on 3/19/25 but were subsequently ignored and/or distorted by the mainstream media. A reporter from USA Today reached out to Rebuild Medicine (my new non-profit) with questions. This is the exchange between my Executive Director and the reporter:

The above text also included links to several CAP guidelines, yet, in the USA Today article that was subsequently written about the case, the reporter 1) took a swipe at my credibility by describing me as a misinformationist, 2) did not even mention the treatment guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia that we had sent him, and 3) included parts of this below statement that the hospital released in response to my video interview. The mendacity of the below statement is astonishing:

“A recent video circulating online contains misleading and inaccurate claims regarding care provided at Covenant Children’s. Patient confidentiality laws preclude us from providing information directly related to this case. What we can say is that our physicians and care teams follow evidence-based protocols and make clinical decisions based on a patient’s evolving condition, diagnostic findings, and the best available medical knowledge. Measles is a highly contagious, potentially life-threatening disease that often creates serious, well-known complications like pneumonia, encephalitis and more.”

CASE #2 – Daisy Hillebrand, Age 8

I received Daisy’s medical records this past Monday via email at 5:55 p.m. Intrigued, I immediately dove in. I began reviewing and taking notes in an Excel spreadsheet because the records were not chronological. The printouts of the electronic medical record totaled 291 pages and came in 6 separate PDF files. It represented the total record for two separate admissions to the ICU of University Medical Center and one to Providence Covenant Children’s Hospital, all again located in Lubbock, Texas.

I worked continuously from 6 p.m. until 1:45 a.m., then put in another 2.5 hours more in the morning. Up until approximately midnight, my working impression of the cause of Daisy’s death was that it indeed was from measles pneumonia. Only after I opened and began reviewing the last file did I find data directly contradicting that impression. I had that initial impression because that was the “working diagnosis” of the ICU team, as documented in their daily notes.

In this case, I will start with my determination of the cause of death in the last admission. Then, I will provide details of the multiple poorly managed hospitalizations (understatement) that she suffered over the 4 weeks leading up to her death.

Cause of death: ARDS secondary to hospital-acquired pneumonia caused by a highly antibiotic-resistant E.Coli “superbug.” Based on the progression and trajectories of her illness, I believe that she contracted the infection from her first ICU admission, which is what caused her to return to the ICU 2 days after that discharge.

One of the tragedies (there were multiple) of this case is that the ICU team in charge of her care when she was re-admitted never considered the possibility of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) until day 6 of 8. For an adult ICU specialist admitting a patient with an infection who was just discharged from an ICU, empiric treatment for hospital-acquired organisms is so basic and routine; I was shocked they did not do this.

In a minor defense of the pediatric team caring for Daisy, there are no published national treatment guidelines with specific antibiotic recommendations for the empiric treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia (I did find one from the University of North Carolina (UNC), however). The first adult guidelines for HAP were published by the American Thoracic Society in 2005. Here we are 20 years later, and, aside from UNC, the field of pediatrics has not gotten around to doing the same. I found a paper by the Cochrane Library that proposed the methodology for creating one, but although published in 2019, it has not been completed yet. The American Academy of Pediatrics should be ashamed.

The problem for the hospital is that the absence of a treatment guideline is not why she died because had they sent a sputum culture on admission, by Day 3, they would have not only identified the organism but would have learned the antibiotic it was sensitive to and could have started it immediately. Her death on Day 8 would have likely and easily been prevented. Although they did send a urine culture, a blood culture, a viral PCR respiratory panel, and a PCR for MRSA and Staphylococcus (all of which were negative), they did not send a sputum culture. For a pneumonia.

For the sake of brevity, each time I detail a deviation from the standard of care in the below review of all three hospital stays, rather than explaining why it violates the standard in depth (and because I trust it will be evident to even laypeople), I will use baseball terminology by writing “strike” to indicate that “they missed the ball.” The failure to send a sputum culture in a patient with pneumonia who recently spent days in an ICU is Strike 1.

The failure to send a sputum culture had another tragic consequence – it allowed the care team, based on the viral respiratory panel being negative (which does not include measles PCR, by the way), to instead 1) assume that measles was the underlying cause on Day 2 and then, 2) immediately stop antibiotics in a seriously ill and infected child. Strike 2.

In the 8 days of her second hospital admission, she only received 5 days of antibiotics, and that is because, despite a rising white cell count in her blood, they did not restart antibiotics until Day 4, when she spiked yet another fever (Strike 3).

Further, during the three days Daisy received no antibiotics, she was given high-dose steroids. Please know that steroids, when paired with appropriate antibacterials, improve outcomes in pneumonia, but giving them without worsens outcomes. They presumably did this because their working diagnosis was “measles pneumonitis,” not bacterial pneumonia. The doctor in charge kept writing things like: “severe pulmonary sequela of measles infection around 3 weeks ago” and “we are concerned that the true extent of her lung injury due to measles is unknowable and it may be an end-stage process given the span of illness and the fact she truly is an outlier.” I don’t know what that last part means except that the clinical reasoning is unclear, and a broader “differential diagnosis” was not generated. At all.

Know that I have long taught my ICU residents and fellows the two guideposts that governed my care plans for critically ill patients. The first is, “If what you are doing is working, keep doing what you are doing.” This means that if their clinical trajectory was one of slow or steady improvement, sending endless diagnostic tests or adding therapies just because they were still ill is most often unnecessary.

The other was, “If what you are doing is not working, change what you are doing.” In this situation, I would re-review all the clinical data and further explore any causes I might be missing, or I would add on treatments that, although not standard, might offer benefit. I would try anything that might turn someone around, as long as the risk/benefit profile was favorable (when someone is persistently deteriorating, risk/benefit ratios change rapidly such that almost any treatment that holds the possibility for benefit is worthwhile to prevent death). In my opinion, at least.

With that in mind, I will say that I was encouraged by the one instance I found of the team “thinking outside the box” and trying a somewhat experimental treatment. They decided to give her intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)! One trial from China in 2015 found that IVIG improved outcomes in children with severe pneumonia (not measles-specific), and another study found that IVIG batches tested in 2021 contained measles-neutralizing antibodies. Good for them for trying something “off protocol.” Problem: they did not give her the IVIG until Day 7, one day before death.

Also, it was not until one day after re-starting antibiotics (Day 6) that they sent a sputum culture (Strike 4 – standard practice is to send a culture at the same time you start antibiotics). This was also the first time the thought that she might have HAP appeared in the record. This thought led them to then change her antibiotic to one that is routinely used for possible HAP (ceftazidime). Problem: The adult guidelines would have dictated that they start Imipenem or Meropenem, but since they don’t have a pediatric guideline published yet, I will not give them a strike for this.

Two days later, on Day 8, she died of refractory hypoxemia – they could no longer get oxygen into her blood via her lungs despite numerous heroic mechanical ventilation maneuvers. This, to me, is a condition that is akin to drowning in pus.

A few hours after her death, the sputum culture they sent on Day 6 was reported in the record (this is what caused me to change my working diagnosis as to the cause of her pneumonia). My jaw dropped as I read it: It showed 4+ growth of “E.Coli,” a nasty bug generally found in our GI tract only. If you don’t know what 4+ means, see this chart below, which explains the “semi-quantitative growth scale” for bacterial cultures:

If you think this can’t get any worse, you would be wrong: next came the panel of susceptibilities to a slew of antibiotics. Read it and weep:

Ampicillin – Resistant, Ampicillin/Sulbactam – Resistant, Aztreonam – Resistant, Cefazolin – Resistant, Cefepime – Resistant, Cefoxitin – Resistant, Ceftriaxone – Resistant, Cefuroxime- Resistant, Ciprofloxacin – Resistant, Levofloxacin – Resistant, Piperacillin – Resistant, Tetracycline – Resistant, Tobramycin – Resistant, and finally and tragically, Ceftazidime- Resistant.

It was sensitive to only a handful of antibiotics, one of which was meropenem, which is what would have been recommended by the Adult HAP Guidelines. Daisy had numerous risk factors for HAP (previous antibiotics, previous ICU, immunosuppressed, really sick, mechanically ventilated). In conclusion, an appropriate differential diagnosis for her pneumonia did not occur until Day 5, and a sputum culture was sent too late for them to discover that the antibiotic they selected was resistant to the organism she died from.

I am going to temporarily interrupt this post to warn you that, in the below reviews of the two hospital admissions she underwent in the week before the above “final” one, the above pattern of error-prone care and missed opportunities to save her life will continue.

HOSPITAL ADMISSION AT UMC 2 DAYS BEFORE THE FINAL ICU STAY

In this hospitalization, which began on 3/21/25, 6 days before the above admission, Daisy presented with typical symptoms of pneumonia along with a chest x-ray showing a left lower lobe process, classic for bacterial pneumonia. Her admitting diagnosis was “viral illness with probable secondary bacterial pneumonia.” Just like in Kaley Fehr’s case at Covenant Hospital, at UMC, they also decided to treat Daisy with the same inexplicable and standard-violating combination of ceftriaxone and vancomycin. Strike 1. However, Daisy did not suffer the same fate as Kaley because whatever bug was making her ill at this point, it appeared that it was sensitive to this combination, plus her mycoplasma test was negative. Near miss though. Not all medical errors lead to harm, and malpractice cannot be established without harm.

Although the mother was not aware that Daisy had a subtle rash on her back on admission, the ER physician suspected it was measles and sent off a PCR test, which returned positive on the day of discharge. OK, so she had measles too.

She was pretty sick lung-wise at first because she required admission to the ICU for oxygen support. However, her oxygen requirements decreased pretty quickly, her appetite improved, her rash began to “heal and fade,” and she was discharged home on oral antibiotics on Day 4. They prescribed her oral cefdinir, which was a fine choice, in my opinion, because she had responded to ceftriaxone in the hospital (a similar antibiotic).

Problem: in the discharge note, the doctor documented that “the parents appeared concerned” with the discharge and then reported that he/she had “reassured them.” Privately, Daisy’s father told me that was the same day her measles test came back positive, and he thinks that is why they sent her out so quickly. He felt she “didn’t look too good” and was concerned. I would have to agree with him based on the fact that she quickly began to get worse upon arriving home such that 2 days later, on 3/26/25, she had to return to the ER to be readmitted with what turned out to be the fatal E.Coli pneumonia episode I detailed above. My thought: she was beginning to fall ill with E.Coli pneumonia as she was being discharged (resistant to the cefdinir she left with).

I hope you have noticed that I have not overused the phrase, “If you think that was bad, it only gets worse.” If you allow me, I will invoke that phrase again here. Read on:

ADMISSION TO COVENANT HOSPITAL TWO DAYS PRIOR TO THE ABOVE UMC ADMISSIONS

If the sequence of events is confusing because I am “going back in time,” let’s change it up and start from the beginning so I can provide you with the timeline from the beginning of her illnesses.

Daisy had a history of chronic tonsillitis and was being scheduled for a tonsillectomy. A month before her death, as per Dr. Richard Bartlett, Daisy was diagnosed with mononucleosis and developed persistent fevers, which continued throughout the month, including all her hospital admissions. Daisy’s father told me that at one point in the first few weeks, she was also diagnosed and treated for strep at another facility, which Dr. Bartlett thinks was Seminole Hospital District (I don’t have the records for that visit). Then, late in the third week of her illnesses, she was admitted to Covenant Children’s Hospital in Lubbock, stayed one night, and was discharged. 2 days later, she was admitted to UMC for the first of her two hospital admissions there. We good with the timeline?

Now, we have to talk about what happened during her one-night stay at Covenant because had she been appropriately treated there, she would never have ended up at UMC, and all of the above would have been avoided.

Briefly, on 3/18/25, she was at a community health clinic where they found her to require oxygen, so she was sent to the ER. She complained of difficulty breathing, abdominal pain, nausea, and inability to eat and was found with thrush on exam. She had a recent Tmax of 103.7. A CT scan of the abdomen and chest was done, which found splenomegaly and a left lower lobe pneumonia surrounded by a small amount of fluid (e.g., a pleural effusion).

She was given IV ceftriaxone (no azithromycin – Strike), corticosteroids, a breathing treatment (albuterol), and a painkiller (Toradol). This was in the ER, and I do not have the records from the ER, just the hospital stay. She was then admitted to Covenant Children’s Hospital with the diagnosis of pneumonia with a “plan to transition to oral antibiotics in the a.m.” Strike 1 for the absence of azithromycin in her regimen. Again. 3rd hospital this has happened at in my reviews of these cases (someone please call the Department of Health in Texas). No sputum culture was ordered, although a blood culture was. Strike 2.

She was given oral amoxicillin and IV ceftriaxone (unnecessarily redundant coverage but not a strike), Motrin, and Tylenol (ugh, but not a strike). By the next day, her oxygen levels had improved, and she was eating OK, so they discharged her. Problem: the only medication she was discharged with, per the record, was the anti-fungal drug nystatin for the thrush. No antibiotics for her pneumonia. Strike 3, and I really mean Strike 3.

What? The only possible defense is that someone forgot what the CT showed (it appears the ED is separate from the hospital) and instead went by the chest X-ray (CXR) they did in the hospital. Why you would do a CXR on the same day she had a CT is beyond me (CTs are much more sophisticated and detailed).

I suspect the CXR caused the problem because it only revealed bronchial wall thickening. It missed the lower lobe process seen on CT, which is not uncommon as CXRs are much less sensitive to diagnosing pneumonia than CTs. The radiologist stated in his report that “bronchial wall thickening can be seen in asthma or viral illnesses.”

Below is the email with my preliminary findings that I sent to Brian Hooker, Chief Scientific Officer at Children’s Health Defense

I did a quick review, not detailed, but this is what I came up with, and I am again absolutely gobsmacked:

1) I can find no lab work in the chart; it appears from her discharge they did not do any

2) The admission note mentions a CT of the abdomen and chest. The CT abdomen revealed splenomegaly, and the CT Chest revealed a lower lobe opacity and a small pleural effusion. The reports are not included; I think they were done in another facility. The CT is diagnostic of bacterial pneumonia ( focal process with an effusion—i.e., not viral).

3) She was given antibiotics while in hospital but not upon discharge

OVERALL IMPRESSION: Left lower lobe bacterial pneumonia and thrush indicating an immunosuppressed status. They gave her one day of antibiotics for this bacterial pneumonia and then discharged her without an oral antibiotic regimen. She was discharged on 3/19. Two days later (3/21) was her first hospitalization to UMC… for a left lower lobe pneumonia, which landed her in the ICU. To me, this is a clear case of a “missed diagnosis.” Had she been given appropriate oral antibiotics upon discharge, the slow-moving train wreck at UMC would likely have been avoided. There are no words for this. I advise any parent or guardian of a young child to move from that area of Texas immediately in the event they ever need competent medical care. This is almost certainly a separate instance of medical malpractice for which this hospital and its pediatricians could be held liable.

Can you guys find out where the CAT scans were done and get records from that visit? It sounds like it was an outside ER or free-standing ER.

My short, narrative summary of what happened to poor Daisy:

Daisy became ill with mononucleosis a month before death, soon followed by a strep infection and then thrush. Fevers persisted throughout, and then three weeks after the mono diagnosis, she was admitted to Covenant Childrens, diagnosed with left lower lobe pneumonia, and treated successfully. However, she was sent home without oral antibiotics. Unsurprisingly, 2 days later, she was admitted to UMC’s ICU with measles and a worsening left lower lobe pneumonia, which was again, despite errors in antibiotic selection, successfully treated, and she was discharged despite concerns by her parents. The measles rash was clearing at this point. Then, 2 days after that, she was re-admitted to UMC’s ICU with a worsening CXR (now involving her right lung) and severely worsened oxygenation. Instead of suspecting a severe hospital-acquired bacterial infection and sending a sputum culture, the presumptive diagnosis was that her lungs were failing from measles pneumonia, and her antibiotics were stopped. She was instead given corticosteroids for “measles pneumonitis.” She continued to deteriorate despite their re-starting antibiotics on Day 4 and giving IVIG on Day 7. She died on Day 8 of what a few hours later was discovered to be a large amount of E.Coli in her sputum that was highly resistant to the antibiotics she was on.

I largely (and atypically for me as a writer) left out the many emotions I felt while writing this review. I will write a separate post to explore my thoughts about these two cases and why I think hospital care is deteriorating throughout the country, and not just in pediatrics. Recent papers have documented significant decreases in Americans’ trust in their hospitals and doctors (and media) compared to before Covid.

Further, these cases are being widely and repeatedly portrayed as “measles deaths” by a pharma-controlled press in an attempt to regenerate enthusiasm for vaccines (IMO by instilling exaggerated fears of measles (over 90% of measles cases are benign, and most complications can be easily treated with competent medical care). If the media continues to do this fear-mongering by using cases of non-measles deaths, public trust will plummet even further (or maybe I should say public distrust will skyrocket further).

I want to thank Dr. Ben Edwards and Dr. Richard Bartlett, who are in Lubbock doing everything they can to keep kids out of the hospital by delivering appropriate and effective outpatient care.

If you appreciate the pro-bono time and effort I put into performing these extensive case reviews and

researching and writing my posts, please consider a paid subscription.

Alberta

Province introducing “Patient-Focused Funding Model” to fund acute care in Alberta

Alberta’s government is introducing a new acute care funding model, increasing the accountability, efficiency and volume of high-quality surgical delivery.

Currently, the health care system is primarily funded by a single grant made to Alberta Health Services to deliver health care across the province. This grant has grown by $3.4 billion since 2018-19, and although Alberta performed about 20,000 more surgeries this past year than at that time, this is not good enough. Albertans deserve surgical wait times that don’t just marginally improve but meet the medically recommended wait times for every single patient.

With Acute Care Alberta now fully operational, Alberta’s government is implementing reforms to acute care funding through a patient-focused funding (PFF) model, also known as activity-based funding, which pays hospitals based on the services they provide.

“The current global budgeting model has no incentives to increase volume, no accountability and no cost predictability for taxpayers. By switching to an activity-based funding model, our health care system will have built-in incentives to increase volume with high quality, cost predictability for taxpayers and accountability for all providers. This approach will increase transparency, lower wait times and attract more surgeons – helping deliver better health care for all Albertans, when and where they need it.”

Activity-based funding is based on the number and type of patients treated and the complexity of their care, incentivizing efficiency and ensuring that funding is tied to the actual care provided to patients. This funding model improves transparency, ensuring care is delivered at the right time and place as multiple organizations begin providing health services across the province.

“Exploring innovative ways to allocate funding within our health care system will ensure that Albertans receive the care they need, when they need it most. I am excited to see how this new approach will enhance the delivery of health care in Alberta.”

Patient-focused, or activity-based, funding has been successfully implemented in Australia and many European nations, including Sweden and Norway, to address wait times and access to health care services, and is currently used in both British Columbia and Ontario in various ways.

“It is clear that we need a new approach to manage the costs of delivering health care while ensuring Albertans receive the care they expect and deserve. Patient-focused funding will bring greater accountability to how health care dollars are being spent while also providing an incentive for quality care.”

This transition is part of Acute Care Alberta’s mandate to oversee and arrange for the delivery of acute care services such as surgeries, a role that was historically performed by AHS. With Alberta’s government funding more surgeries than ever, setting a record with 304,595 surgeries completed in 2023-24 and with 310,000 surgeries expected to have been completed in 2024-25, it is crucial that funding models evolve to keep pace with the growing demand and complexity of services.

“With AHS transitioning to a hospital-based services provider, it’s time we are bold and begin to explore how to make our health care system more efficient and manage the cost of care on a per patient basis. The transition to a PFF model will align funding with patient care needs, based on actual service demand and patient needs, reflecting the communities they serve.”

“Covenant Health welcomes a patient-focused approach to acute care funding that drives efficiency, accountability and performance while delivering the highest quality of care and services for all Albertans. As a trusted acute care provider, this model better aligns funding with outcomes and supports our unwavering commitment to patients.”

“Patient-focused hospital financing ties funding to activity. Hospitals are paid for the services they deliver. Efficiency may improve and surgical wait times may decrease. Further, hospital managers may be more accountable towards hospital spending patterns. These features ensure that patients receive quality care of the highest value.”

Leadership at Alberta Health and Acute Care Alberta will review relevant research and the experience of other jurisdictions, engage stakeholders and define and customize patient-focused funding in the Alberta context. This working group will also identify and run a pilot to determine where and how this approach can best be applied and implemented this fiscal year.

Final recommendations will be provided to the minister of health later this year, with implementation of patient-focused funding for select procedures across the system in 2026.

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoProvince introducing “Patient-Focused Funding Model” to fund acute care in Alberta

-

2025 Federal Election9 hours ago

2025 Federal Election9 hours agoMark Carney To Ban Free Speech if Elected

-

Carbon Tax2 days ago

Carbon Tax2 days agoTrump targets Washington’s climate laws in recent executive order

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoBill Maher Breaks His Silence on His Private Meeting With President Trump

-

Canadian Energy Centre1 day ago

Canadian Energy Centre1 day agoWhy nation-building Canadian resource projects need Indigenous ownership to succeed

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

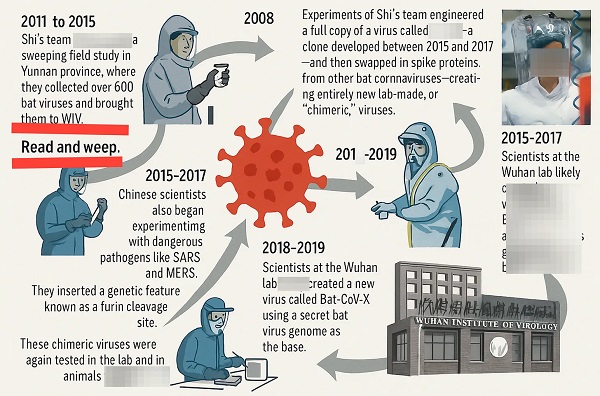

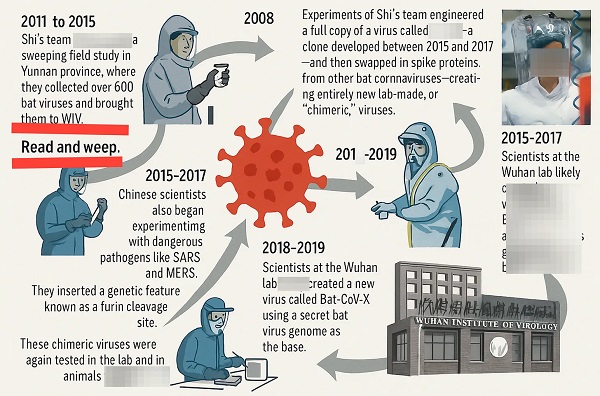

2025 Federal Election1 day agoBLOCKBUSTER REPORT: Canada’s ties to Wuhan Institute of Virology and creation of COVID uncovered by Sam Cooper of The Bureau

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoTrumpian chaos—where we are now and what’s coming for Canada

-

espionage24 hours ago

espionage24 hours agoHong Kong Detains Parents of Activist Frances Hui Amid $1M Bounty, Echoing Election Interference Fears in Canada