Health

Recovered ‘brain dead’ man dancing at sister’s wedding reminds us organ donors are sometimes alive

TJ Hoover and his sister on her wedding day

From LifeSiteNews

Since brain dead people are not dead, it is not surprising that the only multicenter, prospective study of brain death found that the majority of brains from ‘brain dead’ people were not severely damaged at autopsy.

In 2021, a supposedly brain dead man, Anthony Thomas “TJ” Hoover II, opened his eyes and looked around while being wheeled to the operating room to donate his organs. Hospital staff at Baptist Health hospital in Richmond, Kentucky assured his family that these were just “reflexes.”

But organ preservationist Natasha Miller also thought Hoover looked alive. “He was moving around – kind of thrashing. Like, moving, thrashing around on the bed,” said Miller in an NPR interview. “And then when we went over there, you could see he had tears coming down. He was visibly crying.” Thankfully, the procedure was called off, and Hoover was able to recover and even dance at his sister’s wedding this past summer.

Last month, this case was brought before a U.S. House subcommittee investigating organ procurement organizations. Whistleblowers claimed that even after two doctors refused to remove Hoover’s organs, Kentucky Organ Donor Affiliates ordered their staff to find another doctor to perform the surgery.

Because brain death is a social construct and not death itself, I can tell you exactly how many “brain dead” patients are still alive: all of them. When brain death was first proposed by an ad hoc committee at Harvard Medical School in 1968, the committee admitted that these people are not dead, but rather “desperately injured.” They thought that these neurologically injured people were a burden to themselves and others, and that society would be better served if we redefined them as being “dead.” They described their reasoning this way:

Our primary purpose is to define irreversible coma as a new criterion for death. There are two reasons why there is need for a definition: (1) Improvements in resuscitative and supportive measures have led to increased efforts to save those who are desperately injured. Sometimes these efforts have only partial success so that the result is an individual whose heart continues to beat but whose brain is irreversibly damaged. The burden is great on patients who suffer permanent loss of intellect, on their families, on the hospitals, and on those in need of hospital beds already occupied by these comatose patients. (2) Obsolete criteria for the definition of death can lead to controversy in obtaining organs for transplantation.

Since brain dead people are not dead, it is not surprising that the only multicenter, prospective study of brain death found that the majority of brains from “brain dead” people were not severely damaged at autopsy – and 10 actually looked normal. Dr. Gaetano Molinari, one of the study’s principal investigators, wrote:

[D]oes a fatal prognosis permit the physician to pronounce death? It is highly doubtful whether such glib euphemisms as “he’s practically dead,” … “he can’t survive,” … “he has no chance of recovery anyway,” will ever be acceptable legally or morally as a pronouncement that death has occurred.

But history shows that despite Dr. Molinari’s doubts, “brain death,” a prognosis of possible death, went on to be widely accepted as death per se. Brain death was enshrined into US law in 1981 under the Uniform Determination of Death Act. Acceptance of this law has allowed neurologically disabled people to be redefined as “dead” and used as organ donors. Unfortunately, most of these people do not, like TJ Hoover, wake up in time. They suffer death through the harvesting of their organs, a procedure often performed without the benefit of anesthesia.

Happily, some do manage to avoid becoming organ donors and go on to receive proper medical treatment. In 1985, Jennifer Hamann was thrown into a coma after being given a prescription that was incompatible with her epilepsy medication. She could not move or sign that she was awake and aware when she overheard doctors saying that her husband was being “completely unreasonable” because he would not donate her organs. She went on to made a complete recovery and became a registered nurse.

Zack Dunlap was declared brain dead in 2007 following an ATV accident. Even though his cousin demonstrated that Zack reacted to pain, hospital staff told his family that it was just “reflexes.” But as Zack’s reactions became more vigorous, the staff took more notice and called off the organ harvesting team that was just landing via helicopter to take Zack’s organs. Today, Zack leads a fully recovered life.

Colleen Burns was diagnosed “brain dead” after a drug overdose in 2009, but wasn’t given adequate testing and awoke on the operating table just minutes before her organ harvesting surgery. Because the Burns family declined to sue, the hospital only received a slap on the wrist: the State Health Department fined St. Joseph’s Hospital Health Center in Syracuse, New York, just $6,000.

In 2015, George Pickering III was declared brain dead, but his father thought doctors were moving too fast. Armed and dangerous, he held off a SWAT team for three hours, during which time his son began to squeeze his hand on command. “There was a law broken, but it was broken for all the right reasons. I’m here now because of it,” said George III.

Trenton McKinley, a 13-year-old boy, suffered a head injury in 2018 but regained consciousness after his parents signed paperwork to donate his organs. His mother told CBS News that signing the consent to donate allowed doctors to continue Trenton’s intensive care treatment, ultimately giving him time to wake up.

Doctors often say that cases like these prove nothing, and that they are obviously the result of misdiagnosis and medical mistakes. But since all these people were about to become organ donors regardless of whether their diagnoses were correct, I doubt they find the “mistake” excuse comforting.

However, Jahi McMath was indisputably diagnosed as being “brain dead” correctly. She was declared brain dead by three different doctors, she failed three apnea tests, and she had four flat-line EEGs, as well as a cerebral perfusion scan showing “no flow.” But because her parents refused to make her an organ donor and insisted on continuing her medical care, McMath recovered to the point of being able to follow commands. Two neurologists later testified that she was no longer brain dead, but a in minimally conscious state. Her case shows that people correctly declared “brain dead” can still recover.

READ: Woman with no brainwave activity wakes up after hearing her daughter’s voice

Brain death is not death because the brain death concept does not reflect the reality of the phenomenon of death. Therefore, any guideline for its diagnosis will have no basis in scientific facts. People declared brain dead are neurologically disabled, but they are still alive. “Brain dead” organ donation is a concealed form of euthanasia.

Heidi Klessig MD is a retired anesthesiologist and pain management specialist who writes and speaks on the ethics of organ harvesting and transplantation. She is the author of “The Brain Death Fallacy” and her work may be found at respectforhumanlife.com.

2025 Federal Election

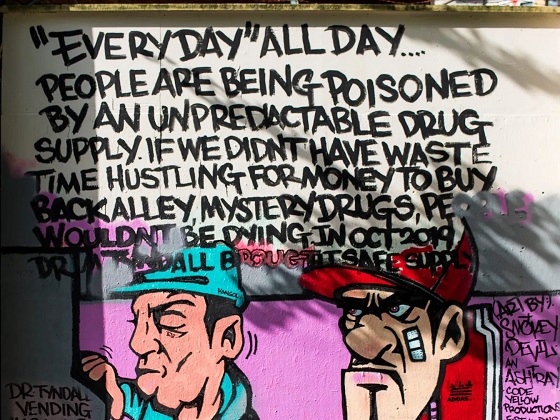

Study links B.C.’s drug policies to more overdoses, but researchers urge caution

By Alexandra Keeler

A study links B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization to more opioid hospitalizations, but experts note its limitations

A new study says B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization policies may have failed to reduce overdoses. Furthermore, the very policies designed to help drug users may have actually increased hospitalizations.

“Neither the safer opioid supply policy nor the decriminalization of drug possession appeared to mitigate the opioid crisis, and both were associated with an increase in opioid overdose hospitalizations,” the study says.

The study has sparked debate, with some pointing to it as proof that B.C.’s drug policies failed. Others have questioned the study’s methodology and conclusions.

“The question we want to know the answer to [but cannot] is how many opioid hospitalizations would have occurred had the policy not have been implemented,” said Michael Wallace, a biostatistician and associate professor at the University of Waterloo.

“We can never come up with truly definitive conclusions in cases such as this, no matter what data we have, short of being able to magically duplicate B.C.”

Jumping to conclusions

B.C.’s controversial safer supply policies provide drug users with prescription opioids as an alternative to toxic street drugs. Its decriminalization policy permitted drug users to possess otherwise illegal substances for personal use.

The peer-reviewed study was led by health economist Hai Nguyen and conducted by researchers from Memorial University in Newfoundland, the University of Manitoba and Weill Cornell Medicine, a medical school in New York City. It was published in the medical journal JAMA Health Forum on March 21.

The researchers used a statistical method to create a “synthetic” comparison group, since there is no ideal control group. The researchers then compared B.C. to other provinces to assess the impact of certain drug policies.

Examining data from 2016 to 2023, the study links B.C.’s safer supply policies to a 33 per cent rise in opioid hospitalizations.

The study says the province’s decriminalization policies further drove up hospitalizations by 58 per cent.

“Neither the safer supply policy nor the subsequent decriminalization of drug possession appeared to alleviate the opioid crisis,” the study concludes. “Instead, both were associated with an increase in opioid overdose hospitalizations.”

The B.C. government rolled back decriminalization in April 2024 in response to widespread concerns over public drug use. This February, the province also officially acknowledged that diversion of safer supply drugs does occur.

The study did not conclusively determine whether the increase in hospital visits was due to diverted safer supply opioids, the toxic illicit supply, or other factors.

“There was insufficient evidence to conclusively attribute an increase in opioid overdose deaths to these policy changes,” the study says.

Nguyen’s team had published an earlier, 2024 study in JAMA Internal Medicine that also linked safer supply to increased hospitalizations. However, it failed to control for key confounders such as employment rates and naloxone access. Their 2025 study better accounts for these variables using the synthetic comparison group method.

The study’s authors did not respond to Canadian Affairs’ requests for comment.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Correlation vs. causation

Chris Perlman, a health data and addiction expert at the University of Waterloo, says more studies are needed.

He believes the findings are weak, as they show correlation but not causation.

“The study provides a small signal that the rates of hospitalization have changed, but I wouldn’t conclude that it can be solely attributed to the safer supply and decrim[inalization] policy decisions,” said Perlman.

He also noted the rise in hospitalizations doesn’t necessarily mean more overdoses. Rather, more people may be reaching hospitals in time for treatment.

“Given that the [overdose] rate may have gone down, I wonder if we’re simply seeing an effect where more persons survive an overdose and actually receive treatment in hospital where they would have died in the pre-policy time period,” he said.

The Nguyen study acknowledges this possibility.

“The observed increase in opioid hospitalizations, without a corresponding increase in opioid deaths, may reflect greater willingness to seek medical assistance because decriminalization could reduce the stigma associated with drug use,” it says.

“However, it is also possible that reduced stigma and removal of criminal penalties facilitated the diversion of safer opioids, contributing to increased hospitalizations.”

Karen Urbanoski, an associate professor in the Public Health and Social Policy department at the University of Victoria, is more critical.

“The [study’s] findings do not warrant the conclusion that these policies are causally associated with increased hospitalization or overdose,” said Urbanoski, who also holds the Canada Research Chair in Substance Use, Addictions and Health Services.

Her team published a study in November 2023 that measured safer supply’s impact on mortality and acute care visits. It found safer supply opioids did reduce overdose deaths.

Critics, however, raised concerns that her study misrepresented its underlying data and showed no statistically significant reduction in deaths after accounting for confounding factors.

The Nguyen study differs from Urbanoski’s. While Urbanoski’s team focused on individual-level outcomes, the Nguyen study analyzed broader, population-level effects, including diversion.

Wallace, the biostatistician, agrees more individual-level data could strengthen analysis, but does not believe it undermines the study’s conclusions. Wallace thinks the researchers did their best with the available data they had.

“We do not have a ‘copy’ of B.C. where the policies weren’t implemented to compare with,” said Wallace.

B.C.’s overdose rate of 775 per 100,000 is well above the national average of 533.

Elenore Sturko, a Conservative MLA for Surrey-Cloverdale, has been a vocal critic of B.C.’s decriminalization and safer supply policies.

“If the government doesn’t want to believe this study, well then I invite them to do a similar study,” she told reporters on March 27.

“Show us the evidence that they have failed to show us since 2020,” she added, referring to the year B.C. implemented safer supply.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

Addiction experts demand witnessed dosing guidelines after pharmacy scam exposed

By Alexandra Keeler

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

An addiction medicine advocacy group is urging B.C. to promptly issue new guidelines for witnessed dosing of drugs dispensed under the province’s controversial safer supply program.

In a March 24 letter to B.C.’s health minister, Addiction Medicine Canada criticized the BC Centre on Substance Use for dragging its feet on delivering the guidelines and downplaying the harms of prescription opioids.

The centre, a government-funded research hub, was tasked by the B.C. government with developing the guidelines after B.C. pledged in February to return to witnessed dosing. The government’s promise followed revelations that many B.C. pharmacies were exploiting rules permitting patients to take safer supply opioids home with them, leading to abuse of the program.

“I think this is just a delay,” said Dr. Jenny Melamed, a Surrey-based family physician and addiction specialist who signed the Addiction Medicine Canada letter. But she urged the centre to act promptly to release new guidelines.

“We’re doing harm and we cannot just leave people where they are.”

Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter also includes recommendations for moving clients off addictive opioids altogether.

“We should go back to evidence-based medicine, where we have medications that work for people in addiction,” said Melamed.

‘Best for patients’

On Feb. 19, the B.C. government said it would return to a witnessed dosing model. This model — which had been in place prior to the pandemic — will require safer supply participants to take prescribed opioids under the supervision of health-care professionals.

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

In its Feb. 19 announcement, the province said new participants in the safer supply program would immediately be subject to the witnessed dosing requirement. For existing clients of the program, new guidelines would be forthcoming.

“The Ministry will work with the BC Centre on Substance Use to rapidly develop clinical guidelines to support prescribers that also takes into account what’s best for patients and their safety,” Kendra Wong, a spokesperson for B.C.’s health ministry, told Canadian Affairs in an emailed statement on Feb. 27.

More than a month later, addiction specialists are still waiting.

According to Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter, the BC Centre on Substance Use posed “fundamental questions” to the B.C. government, potentially causing the delay.

“We’re stuck in a place where the government publicly has said it’s told BCCSU to make guidance, and BCCSU has said it’s waiting for government to tell them what to do,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

This lag has frustrated addiction specialists, who argue the lack of clear guidance is impeding the transition to witnessed dosing and jeopardizing patient care. They warn that permitting take-home drugs leads to more diversion onto the streets, putting individuals at greater risk.

“Diversion of prescribed alternatives expands the number of people using opioids, and dying from hydromorphone and fentanyl use,” reads the letter, which was also co-signed by Dr. Robert Cooper and Dr. Michael Lester. The doctors are founding board members of Addiction Medicine Canada, a nonprofit that advises on addiction medicine and advocates for research-based treatment options.

“We have had people come in [to our clinic] and say they’ve accessed hydromorphone on the street and now they would like us to continue [prescribing] it,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

A spokesperson for the BC Centre on Substance Use declined to comment, referring Canadian Affairs to the Ministry of Health. The ministry was unable to provide comment by the publication deadline.

Big challenges

Under the witnessed dosing model, doctors, nurses and pharmacists will oversee consumption of opioids such as hydromorphone, methadone and morphine in clinics or pharmacies.

The shift back to witnessed dosing will place significant demands on pharmacists and patients. In April 2024, an estimated 4,400 people participated in B.C.’s safer supply program.

Chris Chiew, vice president of pharmacy and health-care innovation at the pharmacy chain London Drugs, told Canadian Affairs that the chain’s pharmacists will supervise consumption in semi-private booths.

Nathan Wong, a B.C.-based pharmacist who left the profession in 2024, fears witnessed dosing will overwhelm already overburdened pharmacists, creating new barriers to care.

“One of the biggest challenges of the retail pharmacy model is that there is a tension between making commercial profit, and being able to spend the necessary time with the patient to do a good and thorough job,” he said.

“Pharmacists often feel rushed to check prescriptions, and may not have the time to perform detailed patient counselling.”

Others say the return to witnessed dosing could create serious challenges for individuals who do not live close to health-care providers.

Shelley Singer, a resident of Cowichan Bay, B.C., on Vancouver Island, says it was difficult to make multiple, daily visits to a pharmacy each day when her daughter was placed on witnessed dosing years ago.

“It was ridiculous,” said Singer, whose local pharmacy is a 15-minute drive from her home. As a retiree, she was able to drive her daughter to the pharmacy twice a day for her doses. But she worries about patients who do not have that kind of support.

“I don’t believe witnessed supply is the way to go,” said Singer, who credits safer supply with saving her daughter’s life.

Melamed notes that not all safer supply medications require witnessed dosing.

“Methadone is under witness dosing because you start low and go slow, and then it’s based on a contingency management program,” she said. “When the urine shows evidence of no other drug, when the person is stable, [they can] take it at home.”

She also noted that Suboxone, a daily medication that prevents opioid highs, reduces cravings and alleviates withdrawal, does not require strict supervision.

Kendra Wong, of the B.C. health ministry, told Canadian Affairs that long-acting medications such as methadone and buprenorphine could be reintroduced to help reduce the strain on health-care professionals and patients.

“There are medications available through the [safer supply] program that have to be taken less often than others — some as far apart as every two to three days,” said Wong.

“Clinicians may choose to transition patients to those medications so that they have to come in less regularly.”

Such an approach would align with Addiction Medicine Canada’s recommendations to the ministry.

The group says it supports supervised dosing of hydromorphone as a short-term solution to prevent diversion. But Melamed said the long-term goal of any addiction treatment program should be to reduce users’ reliance on opioids.

The group recommends combining safer supply hydromorphone with opioid agonist therapies. These therapies use controlled medications to reduce withdrawal symptoms, cravings and some of the risks associated with addiction.

They also recommend limiting unsupervised hydromorphone to a maximum of five 8 mg tablets a day — down from the 30 tablets currently permitted with take-home supplies. And they recommend that doses be tapered over time.

“This protocol is being used with success by clinicians in B.C. and elsewhere,” the letter says.

“Please ensure that the administrative delay of the implementation of your new policy is not used to continue to harm the public.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoPolice Associations Endorse Conservatives. Poilievre Will Shut Down Tent Cities

-

2025 Federal Election17 hours ago

2025 Federal Election17 hours agoStudy links B.C.’s drug policies to more overdoses, but researchers urge caution

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoRed Deer Justice Centre Grand Opening: Building access to justice for Albertans

-

Business2 days ago

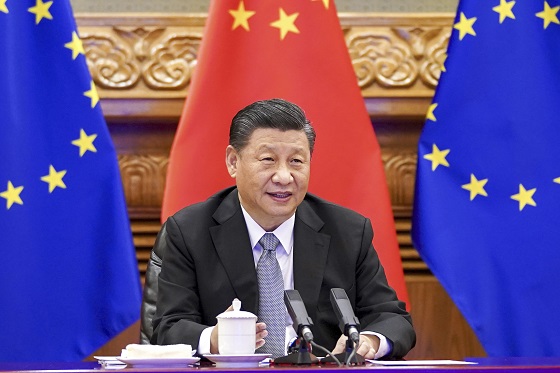

Business2 days agoTrump: China’s tariffs to “come down substantially” after negotiations with Xi

-

conflict2 days ago

conflict2 days agoMarco Rubio says US could soon ‘move on’ from Ukraine conflict: ‘This is not our war’

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoChinese firm unveils palm-based biometric ID payments, sparking fresh privacy concerns

-

International2 days ago

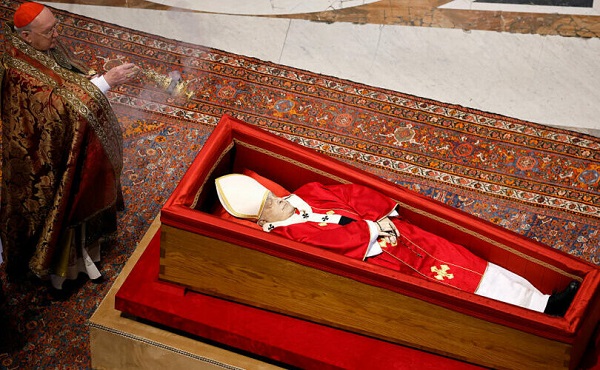

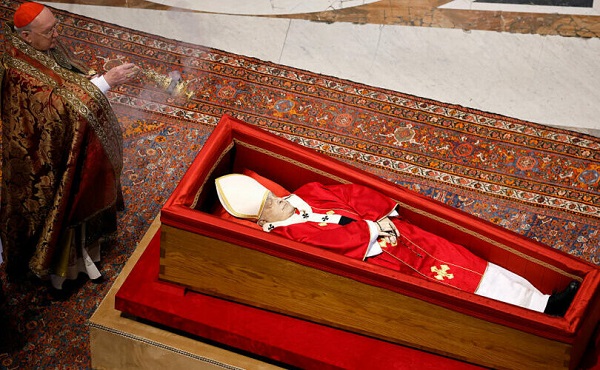

International2 days agoPope Francis’ body on display at the Vatican until Friday

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoConservatives promise to ban firing of Canadian federal workers based on COVID jab status