MacDonald Laurier Institute

Now more than ever we must resist an illiberal turn against free speech

From the MacDonald Laurier Institute

By Kaveh Shahrooz and Aaron Wudrick

The shifting sides of the battle for free speech in the aftermath of Hamas terror

In the wake of Hamas’s brutal attack on Israel and the subsequent armed response, the pitched battle over free speech and cancel-culture in the West has suddenly taken an unexpected turn.

Until last week, it had been the “woke” left deplatforming speakers, calling for boycotts of those who questioned leftist orthodoxy, or firing people for making arguments that progressive cultural arbiters deemed “hateful”. Progressives often denied that cancel-culture even exists, but when pressed would defend punishing the holders of heterodox opinions on the basis that free speech does not mean freedom from consequences.

The political right, often on the receiving end of cancellation attempts, made championing free speech a cornerstone principle.

Almost overnight, these roles were reversed.

In response to deeply offensive rallies and statements coming from the left that seemed to champion (or at least condone) Hamas, it was suddenly the right calling for the government to ban pro-Palestine demonstrations, demanding that those taking part in such protests be fired from their jobs, and even going so far as calling for these people to be blacklisted from future employment opportunities.

Meanwhile, progressive-dominated institutions have conveniently rediscovered a passion for free speech. Harvard University, for example, sits near the bottom of university free speech rankings. Yet suddenly, when faced with criticism for not censuring student groups that applauded Hamas, Harvard President Claudine Gay put out a statement celebrating Harvard’s commitment to free expression.

This is not the first time that the left and right have switched sides on the issue of free speech. In an earlier era, it was the religious right calling for censorship of material it considered to be immoral and the left defending freedom of expression.

The constant shifts in position suggest that many people and institutions want free speech for themselves but their support for those same protections evaporates in the face of ideas they abhor.

But a selective commitment to principle is no commitment at all.

So it is perhaps at this moment, when both right and left have felt the harsh sting of cancel culture, that we can collectively articulate principles that will protect the ability of all sides to express views that others find distasteful.

The first and most important principle that should guide lawmakers and institutions that influence speech rights alike is that society’s zone of permitted speech should be as broad as possible. A free society starts from the premise that all humans are fallible and must continuously search for truth through vigorous debate. Our laws, policies, and norms therefore should be designed to free people to openly question accepted orthodoxies without having to fear financial, professional or reputational ruin.

This should not be mistaken for a ‘absolutist’ interpretation of free speech. Words that incite “imminent lawless action” and public incitement and wilful promotion of hatred are criminalized in the U.S. and Canada, respectively. Most democratic countries also rightly punish fraudulent statements and libelous assertions. This should continue to be the norm in civilized societies.

Nor does it mean that we must refrain from expressing moral outrage or passing judgment on those who hold abhorrent opinions. Offensive speech can, and often should, be met with condemnation and rebuttal from institutions, government and the public at large – but this is not the same thing as outlawing it.

When in doubt, our institutions should err on the side of speech. Substantive institutional punishment for speech that is legally permitted should be rare and reserved for truly extreme cases. Expressing views on controversial topics, be it the view that Israel is to blame for the conflict in Gaza or that there are only two genders, should not lead to a person losing their livelihood or having their right to peaceful protest outlawed.

To achieve this outcome, government officials must show leadership by refusing to cave to demands for censorship. Further, employment laws should be modernized to make it harder for employers to fire someone for political expression outside the workplace. Doing so would blunt the destructive power of cancel culture to threaten livelihoods.

A second principle that will hopefully protect us from the excesses of cancel culture is cultivating a culture of forgiveness and second chances. Everyone makes mistakes, and there should exist a path to redemption – especially in a world where simply Googling someone’s name can reveal the worst mistakes they’ve ever made.

In recent years, as progressives cancelled many people for increasingly minor infractions, we began to see a growing trend of groveling apologies, uncomfortably reminiscent of Maoist struggle sessions. These apologies would often be rejected by a ferocious online mob which, sensing weakness, called for blood. But an unforgiving society in which expressing the wrong idea or even telling an off-colour joke can render one persona non grata indefinitely is, by definition, a highly illiberal one. And it is not one in which any decent person would wish to live.

The solution here is largely cultural. It requires that our institutions not immediately fire or blacklist people when faced with organized pressure tactics to do so. Instead, they should develop thoughtful ways for people who have expressed genuinely repulsive views, not just politically unpopular ones, to learn why their community rejects such views. If the speaker shows genuine remorse and makes amends, they should eventually be forgiven.

The left and the right each portray the other side’s speech as “hate speech” and accuse opponents of “censorship”. But many of these claims are in the eye of the beholder, and still others are made in bad faith.

The effect of this, as both sides have now experienced, has been a poisoned atmosphere. The free speech values that have served liberal democratic societies well for the past few centuries are the antidote. It is time for us to rediscover those values.

Kaveh Shahrooz is a lawyer, human-rights activist and senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Aaron Wudrick is the domestic policy director at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Business

Why a domestic economy upgrade trumps diversification

From the Macdonald Laurier Institute

By Stephan Nagy for Inside Policy

The path to Canadian prosperity lies not in economic decoupling from the US but in strategic modernization within the North American context.

President Donald Trump’s ongoing tariff threats against Canadian exports has sent shockwaves through Ottawa’s political establishment. As businesses from Windsor to Vancouver brace for potential economic fallout, a fundamental question has emerged: Should Canada diversify away from its overwhelming economic dependence on the United States, or should it instead use this moment to modernize and upgrade its economic hard and software within the North American context? The evidence overwhelmingly supports the latter approach in which Canada reduces interprovincial trade barriers and regulations, builds infrastructure to move energy and other resources within Canada, and invests in Canadian human capital and relationships with the US to maximize synergies, stakeholder buy-in and mutual benefit.

The knee-jerk reaction to blame Trump’s economic nationalism misses a crucial point: America’s retreat from championing global free trade began well before his unorthodox political ascendance in 2016. The Obama administration’s signature Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) faced mounting bipartisan skepticism before Trump withdrew from it in 2017. Hillary Clinton, during her presidential campaign, explicitly stated she would oppose the deal, reversing her earlier support. “I will stop any trade deal that kills jobs or holds down wages, including the Trans-Pacific Partnership,” Clinton declared during a campaign speech in Michigan in August 2016.

When President Joe Biden took office, rather than resurrect the TPP, his administration proposed the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). Unlike traditional trade agreements, the IPEF conspicuously omitted market access provisions while emphasizing supply chain resilience and environmental standards. During the IPEF ministerial meeting in Los Angeles in September 2022, U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai specifically noted that the framework “moves beyond the traditional model” of free trade agreements.

These policy evolutions reflect a deeper transformation in American economic thinking: a bipartisan consensus has emerged around industrial policy aimed at rebuilding domestic manufacturing, securing critical supply chains, and maintaining technological leadership against authoritarian competitors such as China.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his Cabinet fundamentally misunderstood these shifts, leading to a series of diplomatic missteps that have damaged Canada-US relations. Most damaging has been a pattern of public rhetoric dismissive of both Trump personally and his MAGA supporters more broadly.

In June 2018, following the G7 summit in Charlevoix, Quebec, Trudeau declared in a press conference that Canada “will not be pushed around” by the United States, characterizing Trump’s tariffs as “insulting.” This prompted Trump to withdraw his endorsement of the summit’s joint statement and label Trudeau as “very dishonest and weak” on Twitter.

Former Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland repeatedly aligned the MAGA movement with authoritarianism. In an August 2022 speech at the Brookings Institution, she characterized Trump supporters as part of a global “anti-democratic movement.” In October 2023, she went further, drawing parallels between MAGA and authoritarian regimes like Russia and China. These statements resonate poorly with nearly half of American voters who supported Trump in recent elections and are borderline disinformation with such exaggerated mischaracterizations of American voters.

Former Foreign Affairs Minister François-Philippe Champagne was caught on camera in December 2022 referring to Trump’s policies as “deranged” while speaking with European counterparts. The video, which social media users circulated widely, further inflamed tensions between the administrations.

Such diplomatic indiscretions might be dismissed as political theatre if they didn’t coincide with concrete policy failures. The Trudeau government neglected critical infrastructure projects that would have strengthened North American economic integration while reducing Canada’s vulnerability to U.S. policy shifts.

To illustrate, Japan and Germany approached Canada to secure liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports as part of their efforts to reduce reliance on Russian energy supplies. Japan expressed high expectations for Canadian LNG during Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s visit, while Germany explored LNG opportunities during Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s visit, emphasizing the urgency of diversifying energy sources due to geopolitical tensions. However, Trudeau rejected these requests, citing a weak business case for LNG exports from Canada’s East Coast due to logistical challenges and lack of infrastructure. Instead, Trudeau shifted focus to clean energy initiatives and critical minerals, reflecting Canada’s evolving industrial policy priorities.

The economic relationship between Canada and the US represents perhaps the most thoroughly integrated bilateral commercial partnership in the world. The statistics alone tell a compelling story: daily two-way trade exceeds $3 billion, supporting approximately 2.7 million Canadian jobs – roughly one-in-six workers in the country.

This integration manifests in countless ways across industries.

For example, in automotive manufacturing, a single vehicle assembled in Ontario typically crosses the Canada-US border seven times during production. A Honda Civic assembled in Alliston, Ontario, contains components from both countries, with engines from Ohio and transmissions from Georgia integrated with Canadian-made bodies and electronics.

The energy infrastructure between the two nations functions essentially as a single system. The North American power grid delivers Canadian hydroelectricity to major US markets, while Canadian refineries process crude oil from both countries. TransCanada’s natural gas pipeline network serves both markets seamlessly, with approximately 3.2 trillion cubic feet flowing between the countries annually.

In aerospace, Bombardier’s commercial aircraft division collaborates with American suppliers like Pratt & Whitney and Collins Aerospace, creating integrated supply chains that span the border. Montreal’s aerospace cluster works in close coordination with counterparts in Seattle and Wichita.

Beyond traditional industries, American-Canadian technological collaboration has accelerated in recent years. For example, the Vector Institute in Toronto has established formal research partnerships with MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, collaborating on foundational AI research. Their joint papers on neural network optimization have been cited more than 3,000 times since 2020.

Quantum computing initiatives at the University of Waterloo’s Institute for Quantum Computing maintain ongoing research exchanges with Google’s quantum computing team in Santa Barbara, California. Their shared work on quantum error correction protocols has advanced the field significantly.

In clean technology, Hydro-Québec’s energy storage division and Massachusetts-based Form Energy announced in 2023 a $240 million joint venture developing grid-scale iron-air batteries to enable renewable energy deployment across North America.

The SCALE.AI supercluster, headquartered in Montreal, includes American tech giants like Microsoft, Amazon, and IBM collaborating with Canadian start-ups on supply chain optimization technologies.

Against this backdrop of deep integration, calls for Canada to diversify away from the US toward markets like China reflect wishful thinking rather than economic reality. Dezan Shira & Associates in its China Briefing advocated expanding commercial ties with Beijing despite China’s documented history of economic coercion toward Canada.

This recommendation ignores the painful lessons of recent history. The arbitrary detention of Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor for over 1,000 days in Chinese prisons, the imposition of punitive restrictions on Canadian agricultural exports following the arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou, and documented interference in Canadian domestic politics all demonstrate the risks of economic dependence on China.

The CD Howe Institute’s March 2025 analysis cites the overwhelming preponderance of trade flows: 76 per cent of Canadian exports go to the United States, compared to just 3.7 per cent to China, 2.4 per cent to the UK, and 2.32 per cent to Japan. As the report notes, “Given geographic proximity, linguistic compatibility, and complementary regulatory frameworks, any significant trade diversification away from the United States would require decades of sustained effort and acceptance of considerably higher transaction costs.”

Rather than pursuing illusory diversification, Canada should focus on strategic economic modernization that positions it as an indispensable partner in America’s industrial revitalization.

First, Canada must dismantle internal trade barriers that fragment its domestic market. The Canadian Federation of Independent Business estimates these interprovincial trade barriers cost the economy $130 billion annually – nearly 7 per cent of GDP. Harmonizing regulations and procurement practices would create a more efficient national market better positioned to integrate with the US economy.

Second, Canada should leverage its critical mineral resources – including lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements – as strategic assets for North American supply chain security. The Minerals Security Partnership launched in 2022 provides a framework for such co-operation, but Canada has yet to fully capitalize on its geological advantages.

Third, Ottawa should accelerate east-west energy infrastructure development to enhance continental energy security. The proposed Energy East pipeline, which would have transported Western Canadian crude to Eastern refineries, fell victim to regulatory hurdles in 2017. Reviving such projects would reduce Eastern Canada’s dependence on imported oil while creating more resilient North American energy networks.

Finally, Canada should position itself as a key contributor to emerging technology initiatives. Trump’s proposed $500 billion AI infrastructure investment represents an opportunity for Canadian AI researchers and companies to integrate more deeply into US innovation ecosystems.

The path to Canadian prosperity lies not in economic decoupling from the US but in strategic modernization within the North American context. The integrated nature of the two economies – built over generations through geographic proximity, shared values, and complementary capabilities – represents a competitive advantage too valuable to abandon.

As American industrial policy evolves to address 21st-century challenges, Canada faces a choice: it can either adapt its economic framework to remain an essential partner in this transformation or risk marginalization through misguided diversification efforts. The evidence overwhelmingly supports the former approach.

For Canada, the answer is smarter, not less, North American integration.

Dr. Stephen Nagy is as a professor at the International Christian University, Tokyo and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Concurrently, he is a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs (JIIA). He serves as the director of policy studies for the Yokosuka Council of Asia Pacific Studies (YCAPS), spearheading their Indo-Pacific Policy Dialogue series. He is currently working on middle-power approaches to great-power competition in the Indo-Pacific.

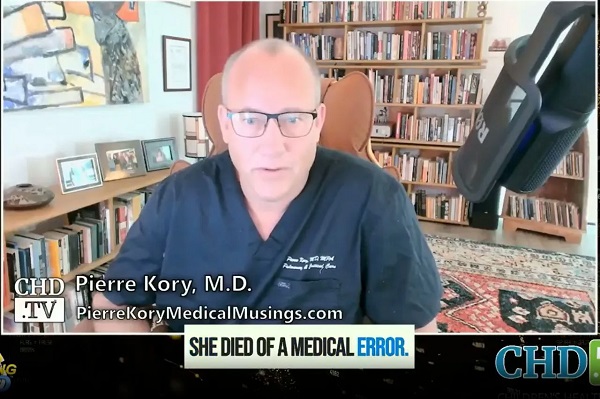

Health

How gender activists stole the media, distorted medicine, and hurt Canadian kids:

By Mia Hughes for Inside Policy

By Mia Hughes for Inside Policy

News outlets abandoned balanced reporting on medical transitions for minors long ago

There is a major medical scandal unfolding in Canada, and our media is fueling it. In gender clinics across the country, doctors put healthy adolescents on invasive medical procedures that can impair fertility, sexual function, and bone density, damage bodily systems, and result in the removal of healthy organs. Teenage girls are being put into menopause, and young men are being chemically and surgically castrated. This is all done without a clear diagnosis or solid scientific evidence that these treatments are safe or beneficial.

Yet Canada’s mainstream media portrays these interventions, euphemistically called “gender-affirming care,” as evidence-based, medically necessary, and lifesaving. Top outlets such as CBC, CTV, and Global present paediatric gender medicine as uncontroversial.

Flawed Coverage Putting Canada’s Youth at Risk

The scandal of paediatric gender medicine contains all the elements of a sensational news story – conspiracy, intrigue, deception, and blackmail. It involves powerful institutions suppressing dissent, whistleblowers risking their careers to speak out, and innocent young people being harmed in the crossfire. There are medical professionals ignoring basic ethical principles, activists influencing policy under the guise of science, and victims being vilified and silenced. All this should prove irresistible to the inquisitive journalistic mind.

Which makes it all the more puzzling that, aside from the National Post, Canada’s mainstream media has opted to ignore the story and instead act as a mouthpiece for extremist trans activists, uncritically echoing their talking points. To understand how harmful and inaccurate the mainstream coverage of this issue is, it is essential to debunk the key claims of the trans activist lobby.

Let’s start with puberty blockers as a fully reversible pause. CBC first reported this claim in 2012, when the puberty suppression experiment was still in its infancy, then it pops up consistently throughout the intervening years, all the way up to the present day and the network’s dismal coverage of England’s Cass Report in 2024. CBC also feeds this misinformation directly to children in a CBC Kids article from 2023.

CTV, Global, the Globe and Mail, and others are equally guilty of spreading this inaccuracy to the public. It is understandable that many Canadians believe puberty blockers are a fully reversible pause and that therefore restricting access to these drugs is unnecessary government overreach. The trouble is the claim is false.

In truth, before Dutch researchers introduced puberty suppression for trans-identified adolescents, studies showed that 63 per cent to 98 per cent of youth eventually outgrew their gender distress. However, once puberty blockers were implemented, nearly all adolescents progressed to irreversible cross-sex hormones, with persistence rates of 98 per cent to 100 per cent. The explanation for this striking reversal of persistence rates is that the cognitive and sexual development that occurs during puberty naturally resolves gender dysphoria in most cases. Blocking puberty, therefore, means blocking the natural cure for gender-related distress.

Yet our mainstream media continues to call puberty blockers reversible because Canada’s “experts” in “gender-affirming care” continue to cling to this belief, despite the mounds of scientific evidence to the contrary. It is the same for the claim that affirming a young person’s transgender identity and providing access to puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgeries amounts to “life-saving care.” The most pernicious of all trans activist misinformation, the transition-or-suicide narrative is ubiquitous in Canada’s mainstream coverage of this controversial medical treatment.

There are many examples. The most reprehensible is in the CBC Kids piece, in which a young trans-identified person is quoted as saying, “If I wasn’t able to start this therapy, honestly, I probably wouldn’t be here anymore.” This content directly contradicts suicide prevention guidelines, which emphasize that the media must never oversimplify or attribute suicide to a single cause because suicide is known to be socially contagious.

The truth is the transition-or-suicide claim rests on exceptionally flimsy scientific evidence. Surveys of trans-identified youth do show increased risk of suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts, but completed suicide in this population is rare. The elevated risk is likely due to co-existing mental health issues that are extremely common in youth who identify as transgender. All systematic reviews to date have found no good quality evidence to support the transition-or-suicide narrative, and the Cass Report and a recent robust study out of Finland reached the same conclusion.

The final most common falsehood repeated by our top news outlets is that very few people regret undergoing these hormonal and surgical procedures. This appears regularly in articles on the subject. Once again, this falsehood appears in the same CBC Kids article, in which children are told that regret is experienced by only “around one per cent of all patients who received gender-affirming surgery, according to a review of 27 studies.” (Of note, the review cited by CBC is among the most poorly conducted study in a field already known for exceptionally low standards, leading one exasperated critic of the paper to ask, “where exactly is the line between incompetence and fraud?”)

These falsehoods remain ever-present in Canada’s reporting on paediatric gender medicine because our journalists have misplaced trust in medical associations, most notably the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH). WPATH, an activist group masquerading as a medical association, has been thoroughly discredited in recent years, but these revelations have failed to penetrate the Canadian media landscape.

Even more remarkably, it is not only the media who were duped by WPATH. Almost every major medical association in North America, including the Canadian Paediatric Society, follows the lead of this fraudulent activist group that sets standards of care based on flimsy science, buries evidence that does not align with its political goals, and believes “eunuch” is a valid gender identity even children can possess.

The WPATH Files, released in March 2024, revealed professionals within WPATH, including a prominent Canadian endocrinologist, are aware that children and adolescents are not capable of understanding the lifelong implications of puberty suppression, that there is significant regret among this cohort, and that gender-affirming clinicians are conducting an unregulated experiment on people who identify as transgender.

How Activists Shaped the Narrative

In October 2011, CBC’s The Passionate Eye aired a documentary titled Transgender Kids. The four children featured in the film were some of the earliest participants in the puberty suppression experiment and the filmmakers compassionately tackled some tough questions, such as how young is too young? And how should parents respond to their child’s desire for these extreme medical interventions?

This was the first time CBC had reported on “transgender children,” a brand-new type of human being only made possible by the puberty suppression experiment. What happened next very likely shaped the way the institution handled the issue going forward.

On January 27, 2012, Egale, which describes itself as a “2SLGBTQI+” charity, published an open letter accusing the CBC of “violence” towards “transgender children” due to repeated instances of misgendering in the documentary. According to Egale, “this significantly increases the likelihood that the viewing public will incorrectly view these children as victims of ‘gender confusion’ and their parents as horribly misguided.” The group demanded a public apology from CBC and recommended that the public broadcaster use the GLAAD media style guide going forward when reporting on trans issues.

Egale’s public response sent a clear warning to Canadian media: questioning whether children and adolescents could truly be transgender or make such life-altering decisions would not be tolerated. As a result, from the outset, activists tied the experiment to change the sex of children to a human rights cause, dictated the tone of media coverage, and effectively forbade genuine journalistic scrutiny of these invasive medical procedures.

The highly publicized suicide of trans-identified teen Leelah Alcorn in 2014 injected the “transition-or-suicide” myth into the Canadian mainstream narrative. Trans activists seized on Alcorn’s suicide note as supposed proof that affirmation and medical interventions saved lives, and from that moment on, our news outlets led parents to believe that questioning their child’s sudden transgender identity or desire for irreversible hormones and surgeries could have fatal consequences.

Having learned its lesson five years previously, in 2017, CBC pulled a second documentary called Transgender Kids: Who Knows Best before it aired after “over a dozen” complaints from Canadian trans activists. The activists claimed the documentary was “harmful, would “disseminate inaccurate information about trans youth and gender dysphoria,” and would “feed transphobia.”

In reality, the documentary was fair and measured. It contained all the standard trans activist talking points but also presented the opposing perspective. It featured Dr. Kenneth Zucker, who highlighted the historically high desistance rates before the introduction of puberty blockers and pointed out that many children experiencing gender distress would likely grow up to be gay.

This is what journalism is meant to do: present the full picture. But in a media landscape dominated by trans activists, news outlets abandoned balanced reporting.

A Lesson from the Past

In May 1941, the Saturday Evening Post published an article with the headline “Turning the Mind Inside Out.” In it, Waldemar Kaempffert, an editor of the New York Times, described a miraculous new brain surgery called a lobotomy that cut “worries, persecution complexes, suicidal intentions, obsessions, indecisiveness and nervous tensions” out of the mind. Kaempffert compared the procedure that involved blindly swinging knives inside a patient’s brain to the delicate work of a watchmaker.

Kaempffert’s article was just one of many glowing media endorsements of what would become one of medicine’s greatest atrocities. With each published piece, word spread, offering desperate families a false sense of hope. Encouraged by the promise of a “cure,” relatives sought lobotomies for their loved ones – including, most famously, the Kennedys, who, in the same year as Kaempffert’s article, subjected their daughter Rosemary to the procedure, with devastating consequences.

The misleading coverage of “gender-affirming care” has a similarly dangerous impact. First, each article reinforces the pseudoscientific notion that some children are transgender, embedding this idea into public consciousness and fueling the social contagion of adolescents adopting trans identities. Then, with every article that exaggerates the benefits of hormones and surgeries and downplays the harms, young people come to believe that this medical treatment is the solution to their pain. However, minors do not sign consent forms. That is the responsibility of parents.

Therefore, consider the real-world consequences of the falsehoods our journalists are propagating. Parents who rely on mainstream media may make disastrous decisions for their child based on ideologically driven narratives.

Glimmers of Courage

Amidst a sea of misinformation, there has been the occasional glimmer of courage. In 2021, CTV’s W5 produced a balanced segment showcasing the voices of detransitioners and asking whether there was adequate safeguarding in youth gender medicine.

In February 2024, Radio-Canada’s Enquête team produced a stunning piece of investigative journalism in which an actress posing as a trans-identified 14-year-old obtained a prescription for testosterone after just a nine-minute appointment at a private gender clinic in Quebec. In response, local trans activists smashed the windows of the Radio-Canada headquarters in Montreal. Then in April 2024, the Globe and Mail published a balanced and thoroughly researched opinion piece calling for a review of Canada’s approach to treating this vulnerable cohort.

CBC’s The National tackled the issue twice, approximately one year apart, and the second showed some measure of improvement in willingness to grapple with the complexity of the issue. However, this is nowhere near enough. These brief glimmers of hope are still drowned out in a sea of activist propaganda.

A Call to Action

One of the greatest challenges in exposing the scandal of paediatric gender medicine is that the truth is so shocking it defies belief. To the average person, it seems impossible that an entire medical field could be hijacked by an unscientific and irrational ideology – that endocrinologists could be chemically castrating healthy adolescents without solid scientific justification, that surgeons could be removing the healthy breasts of teenage girls without any proof of benefit, and that the World Professional Association for Transgender Health could have fraudulently duped the entire medical world into endorsing a reckless, ideology-driven experiment with no scientific underpinning. It sounds like a wild conspiracy theory. Yet every word is true.

Which means now more than ever, journalists must do their job – question, investigate, and expose the corruption of gender medicine. Skeptics need a platform, victims must be heard, and the harms must be scrutinized. Now is the time to plainly state that there is no evidence that “gender-affirming care” is lifesaving, puberty blockers are neither evidence-based nor reversible, and detransition rates are clearly rising. For over a decade, Canadian media have trusted activist-clinicians and the discredited WPATH while ignoring or vilifying those fighting to protect young people. This must end – immediately.

Mia Hughes specializes in pediatric gender medicine, psychiatric epidemics, social contagion and the intersection of trans rights and women’s rights. She is the author of “The WPATH Files” and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoProvince announces plans for nine new ‘urgent care centres’ – redirecting 200,000 hospital visits

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoArkansas approves ivermectin for purchase without prescription

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoDonald Trump suggests Mark Carney will win Canadian election, touts ‘productive call’ with leader

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoElon Musk, DOGE officials reveal ‘astonishing’ government waste, fraud in viral interview

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoRFK Jr. says ‘everything is going to change’ with CDC vaccine policy in Michael Knowles interview

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoNext federal government should recognize Alberta’s important role in the federation

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoLabor Department cancels “America Last” spending spree spanning five continents

-

Education24 hours ago

Education24 hours agoOur Kids Are Struggling To Read. Phonics Is The Easy Fix