Addictions

Kensington Market’s overdose prevention site is saving lives but killing business

Business owners and residents weigh in on the controversial closure of Kensington Market’s overdose prevention site

Toronto’s Kensington Market is a bohemian community knit together by an eclectic symphony of cultures, sounds and flavours.

However, debate has been raging in the community over the potential closure of a local overdose consumption site, which some see as a life-saving resource and others consider a burden on the community.

Grey Coyote, who owns Paradise Bound record shop, believes that the Kensington Market Overdose Prevention Site is fuelling theft and property damage. He plans on shutting his store, which is adjacent to the site, after 25 years of operation.

Other nearby business owners have decided to stay. But they, too, are calling for change.

“The merchants in the market are the ones taking the brunt of this … especially the ones closest to [the overdose prevention site],” said David Beaver, co-owner of Wanda’s Pie in the Sky, a nearby bakery.

“There’s a larger issue at hand here,” Beaver said. “We have to help these people out, but perhaps [the status quo] is not the way to go about it.”

In an effort to change the status quo, Ontario recently passed a law prohibiting overdose prevention sites from operating within 200 metres of schools or daycares. The law could force the Kensington Market Overdose Prevention Site to close, although it is challenging the decision.

Coyote says he plans on leaving the neighbourhood regardless. The high concentration of social programs in the area will make continued theft, property damage and defacement likely, he says.

“They’re all still going to be there,” he said.

Court challenge

Ontario’s decision to close supervised consumption sites near schools and daycares affects 10 sites across the province.

The province plans to transition all nine provincially funded overdose prevention sites into Homelessness and Addiction Recovery Treatment (HART) Hubs. These hubs will offer drug users a range of primary care and housing solutions, but not supervised consumption, needle exchanges or the “safe supply” of prescription drugs.

The tenth site, Kensington Market Overdose Prevention Site, is not eligible to become a HART Hub because it is not provincially funded.

In response, The Neighbourhood Group, the social agency that runs the Kensington site, has filed a lawsuit against the province. It claims the closure order violates the Charter rights of the site’s clients by increasing their risk of death and disease.

“There will be a return of [overdose] deaths that would be preventable,” said Bill Sinclair, CEO of The Neighbourhood Group.

“Our neighbours include people who use these sites and … they are very frightened. They want to know what’s going to happen to them if we close.”

In response to the lawsuit, the province has initiated an investigation on the site’s impact on the community. It has enlisted two ex-police officers to canvas the market, question locals and gather information about the site in preparation for the legal challenge.

“Ontario is collecting evidence from communities affected by supervised consumption sites,” said Keesha Seaton, a media spokesperson for Ontario’s Ministry of the Attorney General.

“Ontario’s responding evidence in the court challenge will be served on January 24.”

|

Kensington Market Overdose Prevention Site in Toronto; Dec. 18, 2024. [Photo credit: Alexandra Keeler]

Bad for business

The Kensington Market Overdose Prevention Site sits at the northern entrance of Spadina Avenue, a key thoroughfare into the heart of Kensington Market. It is located within St. Stephen’s Community House, a former community centre.

The site was added to the community centre in 2018 in response to a surge of overdoses in the area. It is funded through federal grants and community donations.

Within the site’s 200-metre radius are Westside Montessori School, Kensington Kids Early Learning Centre and Bellevue Child Care Centre. Bellevue is operated by The Neighbourhood Group, the same organization that operates the overdose prevention site.

The site serves an average of 154 clients per month. It reversed 50 overdoses in 2024, preventing fatalities.

But while the site has saved lives, shop owners claim it is killing business.

“[Kensington] is a very accepting market and very understanding, but [the overdose prevention site is] just not conducive to business right now,” said Mike Shepherd, owner of Trinity Common beer hall — located across the street from the site — and chair of the Kensington Market Business Improvement Area.

Shepherd says it has become more common to find broken glass, needles and condoms outside his bar in recent years. He has also had to deal with stolen propane heaters and vandalism, including a wine bottle thrown at his car.

Shepherd attributes some of these challenges to a growing homeless population and increased drug use in the neighborhood. He says these issues became particularly acute after Covid hit and the province cut funding for community programs once offered by St. Stephen’s.

Inside his bar, he has handled multiple overdoses, administering naloxone and calling ambulances, and has had to physically remove disruptive patrons.

“I don’t have problems throwing people out of my establishment when they’re … getting violent or causing problems, but my staff shouldn’t have to deal with that,” he said.

“I’m literally watching somebody smoke something from a glass pipe right now,” he said, staring across the street from his bar window as he spoke to Canadian Affairs.

|

Trinity Common beer hall and restaurant in Toronto’s Kensington Market; January 19, 2025. [Photo credit: Alexandra Keeler]

Still, he is empathetic.

“A lot of people who are drug addicted are self-diagnosing for mental traumas,” said Shepherd. “Sometimes, when they go down those deep roads, they go off the tracks.”

Other business owners in the area share similar concerns.

Bobina Attlee, the owner of Otto’s Berlin Döner, has struggled to deal with discarded syringes, stolen bins and sanitation concerns like urine and feces.

These issues prevented her from joining the CaféTO program, which allows restaurants and bars to expand their outdoor dining space during the summer months.

Sid Dichter, owner of Supermarket Restaurant and Bar, has dealt with loitering, break-ins and drug paraphernalia being left behind on his patio day after day.

Some business owners, like Coyote, expressed harsher criticisms.

“Weak politicians and law enforcement have been infiltrated by the retarded, woke mafia,” Coyote said, referring to what he sees as overly lenient harm reduction policies and social programs in “liberal” cities.

Toronto Police Service data show increases in auto and bike thefts and break-and-enters in Kensington Market from 2014 to 2023. Auto thefts rose from 23 in 2014 to 50 in 2023, bike thefts from 92 to 137, and break-and-enters from 103 to 145.

Our content is always free. Subscribe to get BTN’s latest news and analysis, or donate to our journalism fund.

Kensington Market’s city councillor, Dianne Saxe, said she has received numerous complaints from constituents about disorder in the area.

In an email to Canadian Affairs, she cited complaints about “feces, drug trafficking, harassment, shoplifting, theft from yards and porches, trash, masturbation in front of children, and shouting at parents and teachers.”

However, Saxe noted it is difficult to determine what portion of these problems are linked to the overdose prevention site, as opposed to factors like nearby homeless encampments.

Encampments emerged at the Church of Saint Stephen-in-the-Fields on Bellevue Avenue in the spring of 2022 and were cleared in November 2023.

|

Supermarket Bar and Variety in Toronto’s Kensington Market; January 19, 2025. [Photo credit: Alexandra Keeler]

‘Fair share’

Wanda’s Pie in the Sky is located just a few doors down from the Kensington Market Overdose Prevention Site. Beaver, the store’s co-owner, says Wanda’s has always provided food and coffee to clients of the site.

However, issues escalated during the pandemic. Beaver had to deal with incidents like drug use in the restaurant’s restrooms, theft, vandalism and violent outbreaks.

“We try to deal with it on a very compassionate level, but there’s only so much we can do,” said Beaver.

Despite the messes left on his patio, Dichter, who owns the Supermarket Restaurant and Bar, has also developed relationships with site clients.

“I’ve talked to a lot of them, and most of them are very good human beings,” he said. “For the most part, they just have bad luck in life.”

|

Wanda’s Pie in the Sky bakery and cafe in Toronto’s Kensington Market; January 19, 2025. [Photo credit: Alexandra Keeler]

Reverend Canon Maggie Helwig has been a priest at Church of Saint Stephen-in-the-Fields since 2013. She described the overdose prevention site as a safe, well-run space where many people have connected to recovery resources.

“It’s clear to me that the overdose prevention site has been a positive influence in the neighbourhood,” she told Canadian Affairs in an email.

“We need more access to harm reduction, not less, and … closing the site will lead to more public drug use, more deaths from toxic drugs, and fewer people connecting to recovery resources.”

Sinclair, CEO of The Neighbourhood Group, described Kensington Market as “an accepting place for people who are sometimes different or excluded from society … it’s been a place where people have practised tolerance.”

“But sometimes it does feel that some neighbourhoods are doing more than their fair share,” he added.

Shepherd, of Trinity Common beer hall, counted five different social service agencies within a two-block radius of the market. These range from food banks and homeless shelters to the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

“When you have that kind of social services infrastructure in one area, it’s going to draw the people that need it to this area and overburden the neighbourhood,” said Shepherd.

|

Late-Victorian bay-and-gable residential buildings in Toronto’s Kensington Market; January 19, 2025. [Photo credit: Alexandra Keeler]

Systemic issues

Some sources pointed to potential root causes of the growing tensions in Kensington Market.

“We mostly blame the provincial government,” said Beaver, referencing funding cuts by the Ford government that began in 2019.

“They cut the funding to the city, and the city can only do so much with whatever budget they have.”

Provincial funding reductions slashed millions from Toronto Public Health’s budget, straining harm reduction, infectious disease control and community health programs.

“The [overdose prevention site] closure is a provincial decision,” said Councillor Saxe. “I was not consulted [and] I am not aware of any evidence that supports Ford’s decision.

A Toronto Public Health report tabled Jan. 20 warns that closing overdose prevention sites could increase fatal overdoses and strain emergency responders.

The report, prepared by the city’s acting Medical Officer of Health Na-Koshie Lamptey, urges the province to reconsider its decision to exclude safe consumption services from the HART Hubs.

The province’s decision to close sites located near schools and daycares came after a mother of two was fatally shot in a gunfight outside a safe consumption site in Toronto’s Riverdale neighbourhood.

Ontario has also cited crime and public safety concerns as reasons for prohibiting supervised consumption services near centres with children. Police chiefs and sergeants in the Ontario cities of London and Ottawa have additionally raised concerns about prescription drugs dispensed through safer supply programs being diverted to the black market.

For some Kensington Market business owners, the answer is to move overdose prevention sites elsewhere.

“Put our safe injection sites as a wing or an area of the hospital,” said Shepherd, referring to Toronto Western Hospital, on the east side of the Kensington Market neighbourhood.

But another local resident, Andy Stevenson, argues for leaving things as they are. “Leave it alone. Just leave it alone,” said Stevenson, whose home is a five-minute walk from the site. “It’s going to become chaotic if they close it down.”

Stevenson says she has felt a deep connection to the market since her teenage years. She spends her leisure time there and continues to do all her shopping in the area.

“When you choose to live around here, it’s a reality that there are drug addicts, homeless people and street people — It’s a fact of life,” she said.

“So you can’t [complain] about it … move to suburbia.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle. Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

Addiction experts demand witnessed dosing guidelines after pharmacy scam exposed

By Alexandra Keeler

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

An addiction medicine advocacy group is urging B.C. to promptly issue new guidelines for witnessed dosing of drugs dispensed under the province’s controversial safer supply program.

In a March 24 letter to B.C.’s health minister, Addiction Medicine Canada criticized the BC Centre on Substance Use for dragging its feet on delivering the guidelines and downplaying the harms of prescription opioids.

The centre, a government-funded research hub, was tasked by the B.C. government with developing the guidelines after B.C. pledged in February to return to witnessed dosing. The government’s promise followed revelations that many B.C. pharmacies were exploiting rules permitting patients to take safer supply opioids home with them, leading to abuse of the program.

“I think this is just a delay,” said Dr. Jenny Melamed, a Surrey-based family physician and addiction specialist who signed the Addiction Medicine Canada letter. But she urged the centre to act promptly to release new guidelines.

“We’re doing harm and we cannot just leave people where they are.”

Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter also includes recommendations for moving clients off addictive opioids altogether.

“We should go back to evidence-based medicine, where we have medications that work for people in addiction,” said Melamed.

‘Best for patients’

On Feb. 19, the B.C. government said it would return to a witnessed dosing model. This model — which had been in place prior to the pandemic — will require safer supply participants to take prescribed opioids under the supervision of health-care professionals.

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

In its Feb. 19 announcement, the province said new participants in the safer supply program would immediately be subject to the witnessed dosing requirement. For existing clients of the program, new guidelines would be forthcoming.

“The Ministry will work with the BC Centre on Substance Use to rapidly develop clinical guidelines to support prescribers that also takes into account what’s best for patients and their safety,” Kendra Wong, a spokesperson for B.C.’s health ministry, told Canadian Affairs in an emailed statement on Feb. 27.

More than a month later, addiction specialists are still waiting.

According to Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter, the BC Centre on Substance Use posed “fundamental questions” to the B.C. government, potentially causing the delay.

“We’re stuck in a place where the government publicly has said it’s told BCCSU to make guidance, and BCCSU has said it’s waiting for government to tell them what to do,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

This lag has frustrated addiction specialists, who argue the lack of clear guidance is impeding the transition to witnessed dosing and jeopardizing patient care. They warn that permitting take-home drugs leads to more diversion onto the streets, putting individuals at greater risk.

“Diversion of prescribed alternatives expands the number of people using opioids, and dying from hydromorphone and fentanyl use,” reads the letter, which was also co-signed by Dr. Robert Cooper and Dr. Michael Lester. The doctors are founding board members of Addiction Medicine Canada, a nonprofit that advises on addiction medicine and advocates for research-based treatment options.

“We have had people come in [to our clinic] and say they’ve accessed hydromorphone on the street and now they would like us to continue [prescribing] it,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

A spokesperson for the BC Centre on Substance Use declined to comment, referring Canadian Affairs to the Ministry of Health. The ministry was unable to provide comment by the publication deadline.

Big challenges

Under the witnessed dosing model, doctors, nurses and pharmacists will oversee consumption of opioids such as hydromorphone, methadone and morphine in clinics or pharmacies.

The shift back to witnessed dosing will place significant demands on pharmacists and patients. In April 2024, an estimated 4,400 people participated in B.C.’s safer supply program.

Chris Chiew, vice president of pharmacy and health-care innovation at the pharmacy chain London Drugs, told Canadian Affairs that the chain’s pharmacists will supervise consumption in semi-private booths.

Nathan Wong, a B.C.-based pharmacist who left the profession in 2024, fears witnessed dosing will overwhelm already overburdened pharmacists, creating new barriers to care.

“One of the biggest challenges of the retail pharmacy model is that there is a tension between making commercial profit, and being able to spend the necessary time with the patient to do a good and thorough job,” he said.

“Pharmacists often feel rushed to check prescriptions, and may not have the time to perform detailed patient counselling.”

Others say the return to witnessed dosing could create serious challenges for individuals who do not live close to health-care providers.

Shelley Singer, a resident of Cowichan Bay, B.C., on Vancouver Island, says it was difficult to make multiple, daily visits to a pharmacy each day when her daughter was placed on witnessed dosing years ago.

“It was ridiculous,” said Singer, whose local pharmacy is a 15-minute drive from her home. As a retiree, she was able to drive her daughter to the pharmacy twice a day for her doses. But she worries about patients who do not have that kind of support.

“I don’t believe witnessed supply is the way to go,” said Singer, who credits safer supply with saving her daughter’s life.

Melamed notes that not all safer supply medications require witnessed dosing.

“Methadone is under witness dosing because you start low and go slow, and then it’s based on a contingency management program,” she said. “When the urine shows evidence of no other drug, when the person is stable, [they can] take it at home.”

She also noted that Suboxone, a daily medication that prevents opioid highs, reduces cravings and alleviates withdrawal, does not require strict supervision.

Kendra Wong, of the B.C. health ministry, told Canadian Affairs that long-acting medications such as methadone and buprenorphine could be reintroduced to help reduce the strain on health-care professionals and patients.

“There are medications available through the [safer supply] program that have to be taken less often than others — some as far apart as every two to three days,” said Wong.

“Clinicians may choose to transition patients to those medications so that they have to come in less regularly.”

Such an approach would align with Addiction Medicine Canada’s recommendations to the ministry.

The group says it supports supervised dosing of hydromorphone as a short-term solution to prevent diversion. But Melamed said the long-term goal of any addiction treatment program should be to reduce users’ reliance on opioids.

The group recommends combining safer supply hydromorphone with opioid agonist therapies. These therapies use controlled medications to reduce withdrawal symptoms, cravings and some of the risks associated with addiction.

They also recommend limiting unsupervised hydromorphone to a maximum of five 8 mg tablets a day — down from the 30 tablets currently permitted with take-home supplies. And they recommend that doses be tapered over time.

“This protocol is being used with success by clinicians in B.C. and elsewhere,” the letter says.

“Please ensure that the administrative delay of the implementation of your new policy is not used to continue to harm the public.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle

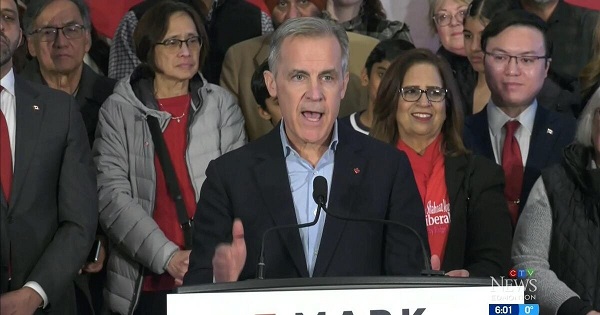

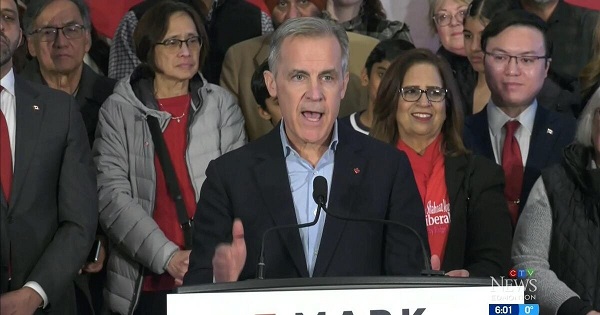

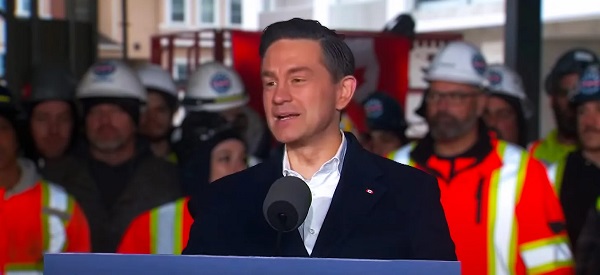

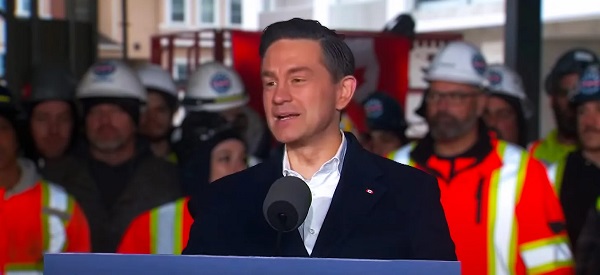

2025 Federal Election

Poilievre to invest in recovery, cut off federal funding for opioids and defund drug dens

From Conservative Party Communications

Poilievre will Make Recovery a Reality for 50,000 Canadians

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre pledged he will bring the hope that our vulnerable Canadians need by expanding drug recovery programs, creating 50,000 new opportunities for Canadians seeking freedom from addiction. At the same time, he will stop federal funding for opioids, defund federal drug dens, and ensure that any remaining sites do not operate within 500 meters of schools, daycares, playgrounds, parks and seniors’ homes, and comply with strict new oversight rules that focus on pathways to treatment.

More than 50,000 people have lost their lives to fentanyl since 2015—more Canadians than died in the Second World War. Poilievre pledged to open a path to recovery while cracking down on the radical Liberal experiment with free access to illegal drugs that has made the crisis worse and brought disorder to local communities.

Specifically, Poilievre will:

- Fund treatment for 50,000 Canadians. A new Conservative government will fund treatment for 50,000 Canadians in treatment centres with a proven record of success at getting people off drugs. This includes successful models like the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre, which helps people recover and reunite with their families, communities, and culture. To ensure the best outcomes, funding will follow results. Where spaces in good treatment programs exist, we will use them, and where they need to expand, these funds will allow that.

- Ban drug dens from being located within 500 metres of schools, daycares, playgrounds, parks, and seniors’ homes and impose strict new oversight rules. Poilievre also pledged to crack down on the Liberals’ reckless experiments with free access to illegal drugs that allow provinces to operate drug sites with no oversight, while pausing any new federal exemptions until evidence justifies they support recovery. Existing federal sites will be required to operate away from residential communities and places where families and children frequent and will now also have to focus on connecting users with treatment, meet stricter regulatory standards or be shut down. He will also end the exemption for fly-by-night provincially-regulated sites.

“After the Lost Liberal Decade, Canada’s addiction crisis has spiralled out of control,” said Poilievre. “Families have been torn apart while children have to witness open drug use and walk through dangerous encampments to get to school. Canadians deserve better than the endless Liberal cycle of crime, despair, and death.”

Since the Liberals were first elected in 2015, our once-safe communities have become sordid and disordered, while more and more Canadians have been lost to the dangerous drugs the Liberals have flooded into our streets. In British Columbia, where the Liberals decriminalized dangerous drugs like fentanyl and meth, drug overdose deaths increased by 200 percent.

The Liberals also pursued a radical experiment of taxpayer-funded hard drugs, which are often diverted and resold to children and other vulnerable Canadians. The Vancouver Police Department has said that roughly half of all hydromorphone seizures were diverted from this hard drugs program, while the Waterloo Regional Police Service and Niagara Regional Police Service said that hydromorphone seizures had exploded by 1,090% and 1,577%, respectively.

Despite the death and despair that is now common on our streets, bizarrely Mark Carney told a room of Liberal supporters that 50,000 fentanyl deaths in Canada is not “a crisis.” He also hand-picked a Liberal candidate who said the Liberals “would be smart to lean into drug decriminalization” and another who said “legalizing all drugs would be good for Canada.”

Carney’s star candidate Gregor Robertson, an early advocate of decriminalization and so-called safe supply, wanted drug dens imposed on communities without any consultation or public safety considerations. During his disastrous tenure as Vancouver Mayor, overdoses increased by 600%.

Alberta has pioneered an approach that offers real hope by adopting a recovery-focused model of care, leading to a nearly 40 percent reduction in drug-poisoning deaths since 2023—three times the decrease seen in British Columbia. However, we must also end the Liberal drug policies that have worsened the crisis and harmed countless lives and families.

To fund this policy, a Conservative government will stop federal funding for opioids, defund federal drug dens, and sue the opioid manufacturers and consulting companies who created this crisis in the first place.

“Canadians deserve better than the Liberal cycle of crime, despair, and death,” said Poilievre. “We will treat addiction with compassion and accountability—not with more taxpayer-funded poison. We will turn hurt into hope by shutting down drug dens, restoring order in our communities, funding real recovery, and bringing our loved ones home drug-free.”

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoOttawa Confirms China interfering with 2025 federal election: Beijing Seeks to Block Joe Tay’s Election

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoNearly Half of “COVID-19 Deaths” Were Not Due to COVID-19 – Scientific Reports Journal

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoHow Canada’s Mainstream Media Lost the Public Trust

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoBREAKING: THE FEDERAL BRIEF THAT SHOULD SINK CARNEY

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoReal Homes vs. Modular Shoeboxes: The Housing Battle Between Poilievre and Carney

-

International17 hours ago

International17 hours agoNew York Times publishes chilling new justification for assisted suicide

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoPOLL: Canadians want spending cuts

-

John Stossel1 day ago

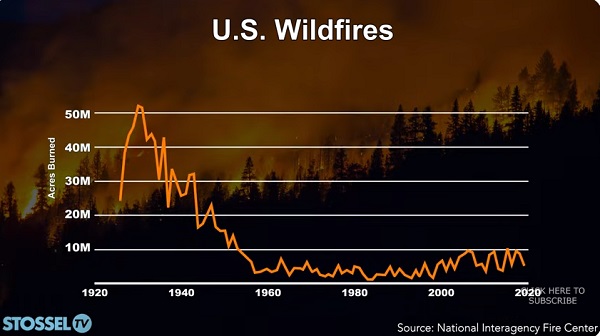

John Stossel1 day agoClimate Change Myths Part 2: Wildfires, Drought, Rising Sea Level, and Coral Reefs