Brownstone Institute

It Was Birx. All Birx.

BY

In two previous articles, I looked into the shady circumstances surrounding Deborah Birx’s appointment to the White House Coronavirus Response Task Force and the laughable lack of actual science behind the claims she used to justify her testing, masking, distancing and lockdown policies.

Considering all that, the questions arise: Who was actually in charge of Deborah Birx and whom was she working with?

But first: Who cares?

Here’s why I think it’s important: If we can show that Birx and the others who imposed totalitarian anti-scientific testing, masking, social distancing, and lockdown policies, knew from the get-go that these policies would not work against an airborne respiratory virus, and nevertheless they imposed them FOR REASONS OTHER THAN PUBLIC HEALTH, then there is no longer acceptable justification for any of those measures.

Furthermore, whatever mountains of post-facto bad science were concocted to rationalize these measures are also completely bunk. Instead of having to go through each ridiculous pseudo-study to demonstrate its scientific worthlessness, we can throw the whole steaming pile in the garbage heap of history, where it belongs, and move on with our lives.

In my admittedly somewhat naive optimism, I also hope that by exposing the non-scientific, anti-public-health origins of the Covid catastrophe, we may lower the chances of it happening again.

And now, back to Birx.

She did not work for or with Trump

We know Birx was definitely not working with President Trump, although she was on a task force ostensibly representing the White House. Trump did not appoint her, nor did the leaders of the Task Force, as Scott Atlas recounts in his revelatory book on White House pandemic lunacy, A Plague Upon Our House. When Atlas asked Task Force members how Birx was appointed, he was surprised to find that “no one seemed to know.” (Atlas, p. 82)

Yet, somehow, Deborah Birx – a former military AIDS researcher and government AIDS ambassador with no training, experience or publications in epidemiology or public health policy – found herself leading a White House Task Force on which she had the power to literally subvert the policy prescriptions of the President of the United States.

As she describes in The Silent Invasion, Birx was shocked when “at the halfway point of our 15 Days to Slow the Spread campaign, President Trump stated that he hoped to lift all restrictions by Easter Sunday.” (Birx, p. 142) She was even more dismayed when “mere days after the president had announced the thirty-day extension of the Slow the Spread campaign to the American public” he became enraged and told her “‘We will never shut down the country again. Never.’” (Birx, p. 152)

Clearly, Trump was not on board with the lockdowns, and every time he was forced to go along with them, he became enraged and lashed out at Birx – the person he believed was forcing him.

Birx laments that “from here on out, everything I worked toward would be harder—in some cases, impossible,” and goes on to say she would basically have to work behind the scenes against the President, having “to adapt to effectively protect the country from the virus that had already silently invaded it.” (Birx, pp. 153-4)

Which brings us back to the question: Where did Birx get the nerve and, more mysteriously, the authority to so blithely act in direct opposition to the President she was supposed to serve, on matters affecting the lives of the entire population of the United States?

Atlas regrets what he thinks was President Trump’s “massive error in judgment.” He argues that Trump acted “against his own gut feeling” and “delegated authority to medical bureaucrats, and then he failed to correct that mistake.” (Atlas, p. 308)

Although I believe massive errors in judgment were not unusual for President Trump, I disagree with Atlas on this one. In the case of the Coronavirus Response Task Force, I actually think there was something much more insidious at play.

Trump had no power over Birx or pandemic response

Dr. Paul Alexander, an epidemiologist and research methodology expert who was recruited to advise the Trump administration on pandemic policy, tells a shocking story in an interview with Jeffrey Tucker, in which bureaucrats at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and lawyers from the Justice Department told him to resign, despite direct orders from President Trump and the White House: “We want you to understand that President Trump has no power,” they reportedly told Alexander. “He cannot tell us what to do.”

Alexander believes these bureaucrats represented the “deep state” which, he was told repeatedly, had decided first not to hire or pay him, and then to get rid of him. Alexander also writes in an upcoming exposé that the entrenched government bureaucracy, particularly at the NIH, CDC, and WHO, used the pandemic response to doom President Trump’s chances for reelection.

Was the entire anti-scientific totalitarian pandemic response, all over the world, a political maneuver to get rid of Trump? It’s possible. I would contend, however, that the politics were only a sideshow to the main event: the engineered virus lab leak and coverup. I believe the “deep state” Alexander repeatedly butted up against was not just the entrenched bureaucracy, but something even deeper and more powerful.

Which brings us back to deep state frontwoman Deborah Birx.

After lamenting Trump’s delegation of authority to “medical bureaucrats,” Scott Atlas also hints at forces beyond Trump’s control. “The Task Force was called ‘the White House Coronavirus Task Force,’” Atlas notes, “but it was not in sync with President Trump. It was directed by Vice President Pence.” (Atlas, p. 306) Yet, whenever Atlas tried to raise questions about Birx’s policies, he was directed to speak with Pence, who then failed to ever address anything with Birx:

“Given that the VP was in charge of the Task Force, shouldn’t the bottom-line advice emanating from it comport with the policies of the administration? But he would never speak with Dr. Birx at all. In fact, (Marc) Short [Pence’s chief of staff], clearly representing the VP’s interests above all else, would do the opposite, telephoning others in the West Wing, imploring friends of mine to tell me to avoid alienating Dr. Birx.” (Atlas, p. 165-6)

Recall that Pence replaced Alex Azar as Task Force director on February 26, 2020 and Birx’s appointment as coordinator, at the instigation of Asst. National Security Advisor Matt Pottinger, came on February 27th. Subsequent to those two appointments, it was Birx who was effectively in charge of United States coronavirus policy.

What was driving that policy, once she took over? As Birx writes, it was the NSC (National Security Council) that appointed her, through Pottinger, and it was her job to “reinforce their warnings” – which, I continue to speculate, were related to the accidental release of an enhanced pandemic potential pathogen from a US-funded lab in Wuhan.

Trump was probably made aware of this, as evidenced not just by his repeated mentions, but by what Time Magazine called his uncharacteristic refusal to explain why he believed it. The magazine quotes Trump saying “I can’t tell you that,” when asked about his belief in the lab leak. And he repeats, “I’m not allowed to tell you that.”

Why in the world was the President of the United States not allowed to override AIDS researcher/diplomat Birx on lockdown policies nor explain to the public why he believed there was a lab leak?

The answer, I believe, is that Trump was uncharacteristically holding back because he was told (by Birx, Pottinger and the military/intelligence/biosecurity interests for whom they worked) that if he did not go along with their policies and proclamations, millions of Americans would die. Why? Because SARS-CoV-2 was not just another zoonotic virus. It was an engineered virus that needed to be contained at all costs.

As Dr. Atlas repeatedly notes with great dismay: “the Task Force doctors were fixated on a single-minded view that all cases of COVID must be stopped or millions of Americans would die.” (Atlas, p. 155-6) [BOLDFACE ADDED]

That was the key message, wielded with great force and success against Trump, his administration, the press, the states, and the public, to suppress any opposition to lockdown policies. Yet the message makes no sense if you believe SARS-CoV-2 is a virus that jumped from a bat to a person in a wet market, severely affecting mostly people who are old and debilitated. It only makes sense if you think, or know, that the virus was engineered to be especially contagious or deadly (even if its behavior in the population at any given moment might not justify that level of alarm).

But, again, before indulging in more speculation, let’s get back to Birx. Who else did she (and her hidden handlers) bulldoze?

She dictated policy to the entire Trump administration

In his book, Atlas observes with puzzlement and consternation that, although Pence was the nominal director of the Task Force, Deborah Birx was the person in charge: “Birx’s policies were enacted throughout the country, in almost every single state, for the entire pandemic—this cannot be denied; it cannot be deflected.” (Atlas, p. 222)

Atlas is “dumbstruck at the lack of leadership in the White House,” in which, “the president was saying one thing while the White House Task Force representative was saying something entirely different, indeed contradictory” and, as he notes, “no one ever set her [Birx] straight on her role.” (Atlas, p. 222-223)

Not only that, but no matter how much Trump, or anyone in the administration, disagreed with Birx, “the White House was held hostage to the anticipated reaction of Dr. Birx” and she “was not to be touched, period.” (Atlas, p. 223)

One explanation for her untouchableness, Atlas suggests, is that Birx and her policies became so popular with the press and public that the administration did not want to “rock the boat” by replacing her before the election. This explanation, however, as Atlas himself realizes, crumbles in the face of what we know about Trump and the media’s hostility towards him:

“They [Trump’s advisors] had convinced him to do exactly the opposite of what he would naturally do in any other circumstance—to disregard his own common sense and allow grossly incorrect policy advice to prevail. … This president, widely known for his signature ‘You’re fired!’ declaration, was misled by his closest political intimates. All for fear of what was inevitable anyway—skewering from an already hostile media.” (Atlas, p. 300-301)

I would suggest, again, the reason for the seemingly inexplicable lack of gumption on Trump’s part to get rid of Birx was not politics, but behind-the-scenes machinations of the (to coin a moniker) lab leak cabal.

Who else was part of this cabal with its hidden agendas and oversized policy influence? Our attention naturally turns to the other members of the Task Force who were presumably co-engineering lockdown policies with Birx. Surprising revelations emerge.

There was no troika. No Birx-Fauci lockdown plan. It was all Birx.

It is universally assumed, by both those in favor and those opposed to the Task Force’s policy prescriptions, that Drs. Deborah Birx, Tony Fauci (head of NIAID at the time) and Bob Redfield (then director of the CDC) worked together to formulate those policies.

The stories told by Birx herself and Task Force infiltrator Scott Atlas suggest otherwise.

Like everyone else, at the onset of his book, Atlas asserts: “The architects of the American lockdown strategy were Dr. Anthony Fauci and Dr. Deborah Birx. With Dr. Robert Redfield… they were the most influential medical members of the White House Coronavirus Task Force.” (Atlas, p. 22)

But as Atlas’s story unfolds, he presents a more nuanced understanding of the power dynamics on the Task Force:

“Fauci’s role surprised me the most. Most of the country, indeed the entire world, assumed that Fauci occupied a directorial role in the Trump administration’s Task Force. I had also thought that from viewing the news,” Atlas admits. However, he continues, “The public presumption of Dr. Fauci’s leadership role on the Task Force itself…could not have been more incorrect. Fauci held massive sway with the public, but he was not in charge of anything specific on the Task Force. He served mainly as a channel for updates on the trials of vaccines and drugs.” (p. 98) [BOLDFACE ADDED]

By the end of the book, Atlas fully revises his initial assessment, strongly emphasizing that, in fact, it was primarily and predominantly Birx who designed and disseminated the lockdown policies:

“Dr. Fauci held court in the public eye on a daily basis, so frequently that many misconstrue his role as being in charge. However, it was really Dr. Birx who articulated Task Force policy. All the advice from the Task Force to the states came from Dr. Birx. All written recommendations about their on-the-ground policies were from Dr. Birx. Dr. Birx conducted almost all the visits to states on behalf of the Task Force.” (Atlas, p. 309-10) [BOLDFACE ADDED]

It may sound jarring and unlikely, given the public perception of Fauci, as Atlas notes. But in Birx’s book the same unexpected picture emerges.

Methinks the lady doth protest too much

As with her bizarrely self-contradictory statements about how she got hired, and her blatantly bogus scientific claims, Birx’s story about her mind-melded closeness with Fauci and Redfield falls apart upon closer examination.

In her book, Birx repeatedly claims she trusts Redfield and Fauci “implicitly to help shape America’s response to the novel coronavirus.” (Birx, p. 31) She says she has “every confidence, based on past performance, that whatever path the virus took, the United States and the CDC would be on top of the situation.” (Birx, p. 32)

Then, almost immediately, she undermines the credibility of those she supposedly trusts, quoting Matt Pottinger as saying she “‘should take over Azar, Fauci, and Redfield’s jobs, because you’re such a better leader than they are.’” (Birx, p. 38-9)

Perhaps she was just giving herself a little pat on the back, one might innocently suggest. But wait. There’s so much more.

Birx claims that in a meeting on January 31 “everything Drs. Fauci and Redfield said about their approach made sense based on the information available to me at that point,” even though “neither of them spoke” about the two issues she was most obsessed with: “asymptomatic silent spread [and] the role testing should play in the response.” (Birx, p. 39)

Then, although she says she “didn’t read too much into this omission,” (p. 39) just two weeks later, “as early as February 13” Birx again mentions “a lack of leadership and direction in the CDC and the White House Coronavirus Task Force.” (p. 54)

So does Debi trust Tony and Bob’s leadership or does she not? The only answer is more self-contradictory obfuscation.

Birx is horrified that nobody is taking the virus as seriously as they should: “then I saw Tony and Bob repeating that the risk to Americans was low,” she reports. “On February 8, Tony said that the chances of contracting the virus were ‘minuscule.’” And, “on February 29, he said, ‘Right now, at this moment, there is no need to change anything you’re doing on a day-to-day basis.’” (Birx, p. 57)

This does not seem like the kind of leader Birx can trust. She half-heartedly tries to excuse Redfield and Fauci, saying “I now believe that Bob and Tony’s words had spoken to the limited data they had access to from the CDC,” and then, in another whiplash moment, “maybe they had data in the United States that I did not.”

Did Tony and Bob provide less dire warnings because they had insufficient data or because they had more data than Birx did? She never clarifies, but regardless, she assures us that she “trusted them” and “felt reassured every day with them on the task force.” (Birx, p. 57)

If I was worried that the virus was not being taken seriously enough, Birx’s reports on Bob and Tony would not be very reassuring, to say the least.

Apparently, Birx herself felt that way too. “I was somewhat disappointed that Bob and Tony weren’t seeing the situation as I was,” she says, when they disagreed with her alarmist assessments of asymptomatic spread. But, she adds, “at least their number supported my belief that this new disease was far more asymptomatic than the flu. I wouldn’t have to push them as far as I needed to push the CDC.” (Birx, p. 78)

Is someone who disagrees with your assessment to the point that you need to push them in your direction also someone you “implicitly trust” to lead the US through the pandemic?

Apparently, not so much.

Although she supposedly trusts Redfield and sleeps well at night knowing he’s on the Task Force, Birx has nothing but disdain and criticism for the CDC – the organization Redfield leads.

“On aggressive testing I planned to have Tom Frieden [CDC director under Obama] help bring the CDC along,” she recounts. “Like me, the CDC wanted to do everything to stop the virus, but the agency needed to align with us on aggressive testing and silent spread.” (p. 122) Which makes one wonder: If she was so closely aligned with Redfield, the head of the CDC, why did Birx need to bring in a former director – in a direct challenge to the sitting one – to “bring the CDC along?” Who is “us” if not Birx, Fauci and Redfield?

Masks were another issue of apparent contention. Birx is frustrated because the CDC, led by her “we’ve-got-each-other’s-back” bestie, Bob Redfield (Birx, p. 31), will not issue strict enough masking guidelines. In fact, she repeatedly throws Bob’s organization under the bus, basically accusing them of causing American deaths: “For many weeks and months to come,” she writes, “I fretted over how many lives could have been saved if the CDC had trusted the public to understand that …masks would do no harm and could potentially do a great deal of good.” (Birx, p. 86)

Apparently, Fauci was not on board with the masking either, as Birx says that “getting the doctors, including Tom [Frieden] and Tony, to be in complete agreement with me about asymptomatic spread was slightly less of a priority. As with masks, I knew I could return to that issue as soon as I got their buy-in on our recommendations.” (Birx, p. 123)

Who is making “our recommendations” if not Birx, Fauci and Redfield?

The myth of the troika

Whether or not she trusted them (and it’s hard to believe, based on her own accounts, that she did), it was apparently very important to Birx that she, Fauci and Redfield appear as a single entity with no disagreements whatsoever.

When Scott Atlas, an outsider not privy to whatever power plays were happening on the Task Force, came in, his presence apparently rattled Birx (Atlas, p. 83-4), and for good reason. Atlas immediately noticed strange goings-on. In his book, he repeatedly uses words like “bizarre,” “odd” and “uncanny” to describe how Fauci, Redfield and Birx behaved. Most notably, they never ever questioned or disagreed with one another in Task Force meetings. Not ever.

“They shared thought processes and views to an uncanny level,” Atlas writes, then reiterates that “there was virtually no disagreement among them.” What he saw “was an amazing consistency, as though there were an agreed-upon complicity” (Atlas, pp. 99-100). They “virtually always agreed, literally never challenging one another.” (p. 101) [BOLDFACE ADDED]

An agreed-upon complicity? Uncanny agreement? Based on all of the disagreements reported by Birx and her repeated questioning and undermining of Bob and Tony’s authority, how can this be explained?

I would contend that in order to obscure the extent to which Birx alone was in charge of Task Force policy, the other doctors were compelled to present a facade of complete agreement. Otherwise, as with any opposition to, or even discussion of, potential harms of lockdown policies, “millions of Amercans would die.”

This assessment is strengthened by Atlas’s ongoing bafflement and distress at how the Task Force – and particularly the doctors/scientists who were presumably formulating policy based on data and research – functioned:

“I never saw them act like scientists, digging into the numbers to verify the very trends that formed the basis of their reactive policy pronouncements. They did not act like researchers, using critical thinking to dissect the published science or differentiate a correlation from a cause. They certainly did not show a physician’s clinical perspective. With their single-minded focus, they did not even act like public health experts.” (Atlas, p. 176)

Atlas was surprised, indeed stunned, that “No one on the Task Force presented any data” to justify lockdowns or to contradict the evidence on lockdown harms that Atlas presented. (Atlas, p. 206) More specifically, no data or research was ever presented (except by Atlas) to contradict or question anything Birx said. “Until I arrived,” Atlas observes, “no one had challenged anything she said during her six months as the Task Force Coordinator.” (Atlas, p. 234) [BOLDFACE ADDED]

Atlas cannot explain what he’s witnessing. “That was all part of the puzzle of the Task Force doctors,” he states. “There was a lack of scientific rigor in meetings I attended. I never saw them question the data. The striking uniformity of opinion by Birx, Redfield, Fauci, and (Brett) Giroir [former Admiral and Task Force “testing czar”] was not anything like what I had seen in my career in academic medicine.” (Atlas, p. 244)

How can we explain the puzzle of this uncanny apparent complicity by the Task Force troika?

Methinks the intelligence agent also doth protest too much

An interesting hint comes from the string of anecdotes comprising Matthew Lawrence’s New Yorker article “The Plague Year.” Lawrence writes that Matt Pottinger (the NSC liaison to Birx) tried to convince Task Force members that masking could stop the virus “‘dead in its tracks’” but his views “stirred up surprisingly rigid responses from the public-health contingent.” Lawrence continues to report that “In Pottinger’s opinion, when Redfield, Fauci, Birx, and (Stephen) Hahn spoke, it could sound like groupthink,” implying that those were the members of the “public-health contingent” who did not agree with Pottinger’s masking ideas.

But wait. We just noted Birx’s frustration, indeed deep regret, that the CDC led by Redfield, as well as Fauci (and even Frieden) did not agree with her ideas on asymptomatic spread and masking. So why does Pottinger imply that she and the “public-health contingent” of the Task Force were group-thinking this issue, against him?

I would suggest that the only way to make sense of these contradictions within Birx’s narrative and between her, Atlas and Pottinger’s stories, is if we understand “align with us” and “our recommendations” to refer not to the perceived Birx-Fauci-Redfield troika, but to the Birx-Pottinger-lab leak cabal that was actually running the show.

In fact, Birx and Pottinger put so much effort into insisting on the solidarity of the troika, even when it contradicts their own statements, that the question inevitably arises: what do they have to gain from it? The benefit of insisting that Birx was allied with Fauci, Redfield and the “public-health contingent” on the Task Force, I would argue, is that this deflects attention from the Birx-Pottinger-cabal non-public-health alliance.

Her authority and policies emanated from a hidden source

The explanation of Atlas’s perceived “puzzle of the Task Force doctors” that makes the most sense to me is that Deborah Birx, in contrast and often in opposition to the other doctors on the Task Force, represented the interests of what I’m calling the lab leak cabal: those not just in the US but in the international intelligence/biosecurity community who needed to cover up a potentially devastating lab leak and who wanted to impose draconian lockdown measures such as the world had never known.

Who exactly they were and why they needed lockdowns are subjects of ongoing investigations.

In the meantime, once we separate Birx from Trump, from the rest of the administration, and from the others on the Task Force, we can see clearly that her single-minded and scientifically nonsensical emphasis on silent spread and asymptomatic testing was geared toward a single goal: to scare everyone so much that lockdowns would appear to be a sensible policy. This is the same strategy that was, uncannily in my opinion, implemented almost to the letter in nearly every other country around the world. But that’s for the next article.

I’ll close this chapter of the Birx riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, with Scott Atlas’s report of his parting conversation with President Trump:

“‘You were right about everything, all along the way,’” Trump said to Atlas. “‘And you know what? You were also right about something else. Fauci wasn’t the biggest problem of all of them. It really wasn’t him. You were right about that.’ I found myself nodding as I held the phone in my hand,” Atlas says. “I knew exactly whom he was talking about.” (Atlas, p. 300)

And now, so do we.

Brownstone Institute

The Unmasking of Vaccine Science

From the Brownstone Institute

By

I recently purchased Aaron Siri’s new book Vaccines, Amen. As I flipped though the pages, I noticed a section devoted to his now-famous deposition of Dr Stanley Plotkin, the “godfather” of vaccines.

I’d seen viral clips circulating on social media, but I had never taken the time to read the full transcript — until now.

Siri’s interrogation was methodical and unflinching…a masterclass in extracting uncomfortable truths.

A Legal Showdown

In January 2018, Dr Stanley Plotkin, a towering figure in immunology and co-developer of the rubella vaccine, was deposed under oath in Pennsylvania by attorney Aaron Siri.

The case stemmed from a custody dispute in Michigan, where divorced parents disagreed over whether their daughter should be vaccinated. Plotkin had agreed to testify in support of vaccination on behalf of the father.

What followed over the next nine hours, captured in a 400-page transcript, was extraordinary.

Plotkin’s testimony revealed ethical blind spots, scientific hubris, and a troubling indifference to vaccine safety data.

He mocked religious objectors, defended experiments on mentally disabled children, and dismissed glaring weaknesses in vaccine surveillance systems.

A System Built on Conflicts

From the outset, Plotkin admitted to a web of industry entanglements.

He confirmed receiving payments from Merck, Sanofi, GSK, Pfizer, and several biotech firms. These were not occasional consultancies but long-standing financial relationships with the very manufacturers of the vaccines he promoted.

Plotkin appeared taken aback when Siri questioned his financial windfall from royalties on products like RotaTeq, and expressed surprise at the “tone” of the deposition.

Siri pressed on: “You didn’t anticipate that your financial dealings with those companies would be relevant?”

Plotkin replied: “I guess, no, I did not perceive that that was relevant to my opinion as to whether a child should receive vaccines.”

The man entrusted with shaping national vaccine policy had a direct financial stake in its expansion, yet he brushed it aside as irrelevant.

Contempt for Religious Dissent

Siri questioned Plotkin on his past statements, including one in which he described vaccine critics as “religious zealots who believe that the will of God includes death and disease.”

Siri asked whether he stood by that statement. Plotkin replied emphatically, “I absolutely do.”

Plotkin was not interested in ethical pluralism or accommodating divergent moral frameworks. For him, public health was a war, and religious objectors were the enemy.

He also admitted to using human foetal cells in vaccine production — specifically WI-38, a cell line derived from an aborted foetus at three months’ gestation.

Siri asked if Plotkin had authored papers involving dozens of abortions for tissue collection. Plotkin shrugged: “I don’t remember the exact number…but quite a few.”

Plotkin regarded this as a scientific necessity, though for many people — including Catholics and Orthodox Jews — it remains a profound moral concern.

Rather than acknowledging such sensitivities, Plotkin dismissed them outright, rejecting the idea that faith-based values should influence public health policy.

That kind of absolutism, where scientific aims override moral boundaries, has since drawn criticism from ethicists and public health leaders alike.

As NIH director Jay Bhattacharya later observed during his 2025 Senate confirmation hearing, such absolutism erodes trust.

“In public health, we need to make sure the products of science are ethically acceptable to everybody,” he said. “Having alternatives that are not ethically conflicted with foetal cell lines is not just an ethical issue — it’s a public health issue.”

Safety Assumed, Not Proven

When the discussion turned to safety, Siri asked, “Are you aware of any study that compares vaccinated children to completely unvaccinated children?”

Plotkin replied that he was “not aware of well-controlled studies.”

Asked why no placebo-controlled trials had been conducted on routine childhood vaccines such as hepatitis B, Plotkin said such trials would be “ethically difficult.”

That rationale, Siri noted, creates a scientific blind spot. If trials are deemed too unethical to conduct, then gold-standard safety data — the kind required for other pharmaceuticals — simply do not exist for the full childhood vaccine schedule.

Siri pointed to one example: Merck’s hepatitis B vaccine, administered to newborns. The company had only monitored participants for adverse events for five days after injection.

Plotkin didn’t dispute it. “Five days is certainly short for follow-up,” he admitted, but claimed that “most serious events” would occur within that time frame.

Siri challenged the idea that such a narrow window could capture meaningful safety data — especially when autoimmune or neurodevelopmental effects could take weeks or months to emerge.

Siri pushed on. He asked Plotkin if the DTaP and Tdap vaccines — for diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis — could cause autism.

“I feel confident they do not,” Plotkin replied.

But when shown the Institute of Medicine’s 2011 report, which found the evidence “inadequate to accept or reject” a causal link between DTaP and autism, Plotkin countered, “Yes, but the point is that there were no studies showing that it does cause autism.”

In that moment, Plotkin embraced a fallacy: treating the absence of evidence as evidence of absence.

“You’re making assumptions, Dr Plotkin,” Siri challenged. “It would be a bit premature to make the unequivocal, sweeping statement that vaccines do not cause autism, correct?”

Plotkin relented. “As a scientist, I would say that I do not have evidence one way or the other.”

The MMR

The deposition also exposed the fragile foundations of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

When Siri asked for evidence of randomised, placebo-controlled trials conducted before MMR’s licensing, Plotkin pushed back: “To say that it hasn’t been tested is absolute nonsense,” he said, claiming it had been studied “extensively.”

Pressed to cite a specific trial, Plotkin couldn’t name one. Instead, he gestured to his own 1,800-page textbook: “You can find them in this book, if you wish.”

Siri replied that he wanted an actual peer-reviewed study, not a reference to Plotkin’s own book. “So you’re not willing to provide them?” he asked. “You want us to just take your word for it?”

Plotkin became visibly frustrated.

Eventually, he conceded there wasn’t a single randomised, placebo-controlled trial. “I don’t remember there being a control group for the studies, I’m recalling,” he said.

The exchange foreshadowed a broader shift in public discourse, highlighting long-standing concerns that some combination vaccines were effectively grandfathered into the schedule without adequate safety testing.

In September this year, President Trump called for the MMR vaccine to be broken up into three separate injections.

The proposal echoed a view that Andrew Wakefield had voiced decades earlier — namely, that combining all three viruses into a single shot might pose greater risk than spacing them out.

Wakefield was vilified and struck from the medical register. But now, that same question — once branded as dangerous misinformation — is set to be re-examined by the CDC’s new vaccine advisory committee, chaired by Martin Kulldorff.

The Aluminium Adjuvant Blind Spot

Siri next turned to aluminium adjuvants — the immune-activating agents used in many childhood vaccines.

When asked whether studies had compared animals injected with aluminium to those given saline, Plotkin conceded that research on their safety was limited.

Siri pressed further, asking if aluminium injected into the body could travel to the brain. Plotkin replied, “I have not seen such studies, no, or not read such studies.”

When presented with a series of papers showing that aluminium can migrate to the brain, Plotkin admitted he had not studied the issue himself, acknowledging that there were experiments “suggesting that that is possible.”

Asked whether aluminium might disrupt neurological development in children, Plotkin stated, “I’m not aware that there is evidence that aluminum disrupts the developmental processes in susceptible children.”

Taken together, these exchanges revealed a striking gap in the evidence base.

Compounds such as aluminium hydroxide and aluminium phosphate have been injected into babies for decades, yet no rigorous studies have ever evaluated their neurotoxicity against an inert placebo.

This issue returned to the spotlight in September 2025, when President Trump pledged to remove aluminium from vaccines, and world-leading researcher Dr Christopher Exley renewed calls for its complete reassessment.

A Broken Safety Net

Siri then turned to the reliability of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) — the primary mechanism for collecting reports of vaccine-related injuries in the United States.

Did Plotkin believe most adverse events were captured in this database?

“I think…probably most are reported,” he replied.

But Siri showed him a government-commissioned study by Harvard Pilgrim, which found that fewer than 1% of vaccine adverse events are reported to VAERS.

“Yes,” Plotkin said, backtracking. “I don’t really put much faith into the VAERS system…”

Yet this is the same database officials routinely cite to claim that “vaccines are safe.”

Ironically, Plotkin himself recently co-authored a provocative editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, conceding that vaccine safety monitoring remains grossly “inadequate.”

Experimenting on the Vulnerable

Perhaps the most chilling part of the deposition concerned Plotkin’s history of human experimentation.

“Have you ever used orphans to study an experimental vaccine?” Siri asked.

“Yes,” Plotkin replied.

“Have you ever used the mentally handicapped to study an experimental vaccine?” Siri asked.

“I don’t recollect…I wouldn’t deny that I may have done so,” Plotkin replied.

Siri cited a study conducted by Plotkin in which he had administered experimental rubella vaccines to institutionalised children who were “mentally retarded.”

Plotkin stated flippantly, “Okay well, in that case…that’s what I did.”

There was no apology, no sign of ethical reflection — just matter-of-fact acceptance.

Siri wasn’t done.

He asked if Plotkin had argued that it was better to test on those “who are human in form but not in social potential” rather than on healthy children.

Plotkin admitted to writing it.

Siri established that Plotkin had also conducted vaccine research on the babies of imprisoned mothers, and on colonised African populations.

Plotkin appeared to suggest that the scientific value of such studies outweighed the ethical lapses—an attitude that many would interpret as the classic ‘ends justify the means’ rationale.

But that logic fails the most basic test of informed consent. Siri asked whether consent had been obtained in these cases.

“I don’t remember…but I assume it was,” Plotkin said.

Assume?

This was post-Nuremberg research. And the leading vaccine developer in America couldn’t say for sure whether he had properly informed the people he experimented on.

In any other field of medicine, such lapses would be disqualifying.

A Casual Dismissal of Parental Rights

Plotkin’s indifference to experimenting on disabled children didn’t stop there.

Siri asked whether someone who declined a vaccine due to concerns about missing safety data should be labelled “anti-vax.”

Plotkin replied, “If they refused to be vaccinated themselves or refused to have their children vaccinated, I would call them an anti-vaccination person, yes.”

Plotkin was less concerned about adults making that choice for themselves, but he had no tolerance for parents making those choices for their own children.

“The situation for children is quite different,” said Plotkin, “because one is making a decision for somebody else and also making a decision that has important implications for public health.”

In Plotkin’s view, the state held greater authority than parents over a child’s medical decisions — even when the science was uncertain.

The Enabling of Figures Like Plotkin

The Plotkin deposition stands as a case study in how conflicts of interest, ideology, and deference to authority have corroded the scientific foundations of public health.

Plotkin is no fringe figure. He is celebrated, honoured, and revered. Yet he promotes vaccines that have never undergone true placebo-controlled testing, shrugs off the failures of post-market surveillance, and admits to experimenting on vulnerable populations.

This is not conjecture or conspiracy — it is sworn testimony from the man who helped build the modern vaccine program.

Now, as Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. reopens long-dismissed questions about aluminium adjuvants and the absence of long-term safety studies, Plotkin’s once-untouchable legacy is beginning to fray.

Republished from the author’s Substack

Brownstone Institute

Bizarre Decisions about Nicotine Pouches Lead to the Wrong Products on Shelves

From the Brownstone Institute

A walk through a dozen convenience stores in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, says a lot about how US nicotine policy actually works. Only about one in eight nicotine-pouch products for sale is legal. The rest are unauthorized—but they’re not all the same. Some are brightly branded, with uncertain ingredients, not approved by any Western regulator, and clearly aimed at impulse buyers. Others—like Sweden’s NOAT—are the opposite: muted, well-made, adult-oriented, and already approved for sale in Europe.

Yet in the United States, NOAT has been told to stop selling. In September 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued the company a warning letter for offering nicotine pouches without marketing authorization. That might make sense if the products were dangerous, but they appear to be among the safest on the market: mild flavors, low nicotine levels, and recyclable paper packaging. In Europe, regulators consider them acceptable. In America, they’re banned. The decision looks, at best, strange—and possibly arbitrary.

What the Market Shows

My October 2025 audit was straightforward. I visited twelve stores and recorded every distinct pouch product visible for sale at the counter. If the item matched one of the twenty ZYN products that the FDA authorized in January, it was counted as legal. Everything else was counted as illegal.

Two of the stores told me they had recently received FDA letters and had already removed most illegal stock. The other ten stores were still dominated by unauthorized products—more than 93 percent of what was on display. Across all twelve locations, about 12 percent of products were legal ZYN, and about 88 percent were not.

The illegal share wasn’t uniform. Many of the unauthorized products were clearly high-nicotine imports with flashy names like Loop, Velo, and Zimo. These products may be fine, but some are probably high in contaminants, and a few often with very high nicotine levels. Others were subdued, plainly meant for adult users. NOAT was a good example of that second group: simple packaging, oat-based filler, restrained flavoring, and branding that makes no effort to look “cool.” It’s the kind of product any regulator serious about harm reduction would welcome.

Enforcement Works

To the FDA’s credit, enforcement does make a difference. The two stores that received official letters quickly pulled their illegal stock. That mirrors the agency’s broader efforts this year: new import alerts to detain unauthorized tobacco products at the border (see also Import Alert 98-06), and hundreds of warning letters to retailers, importers, and distributors.

But effective enforcement can’t solve a supply problem. The list of legal nicotine-pouch products is still extremely short—only a narrow range of ZYN items. Adults who want more variety, or stores that want to meet that demand, inevitably turn to gray-market suppliers. The more limited the legal catalog, the more the illegal market thrives.

Why the NOAT Decision Appears Bizarre

The FDA’s own actions make the situation hard to explain. In January 2025, it authorized twenty ZYN products after finding that they contained far fewer harmful chemicals than cigarettes and could help adult smokers switch. That was progress. But nine months later, the FDA has approved nothing else—while sending a warning letter to NOAT, arguably the least youth-oriented pouch line in the world.

The outcome is bad for legal sellers and public health. ZYN is legal; a handful of clearly risky, high-nicotine imports continue to circulate; and a mild, adult-market brand that meets European safety and labeling rules is banned. Officially, NOAT’s problem is procedural—it lacks a marketing order. But in practical terms, the FDA is punishing the very design choices it claims to value: simplicity, low appeal to minors, and clean ingredients.

This approach also ignores the differences in actual risk. Studies consistently show that nicotine pouches have far fewer toxins than cigarettes and far less variability than many vapes. The biggest pouch concerns are uneven nicotine levels and occasional traces of tobacco-specific nitrosamines, depending on manufacturing quality. The serious contamination issues—heavy metals and inconsistent dosage—belong mostly to disposable vapes, particularly the flood of unregulated imports from China. Treating all “unauthorized” products as equally bad blurs those distinctions and undermines proportional enforcement.

A Better Balance: Enforce Upstream, Widen the Legal Path

My small Montgomery County survey suggests a simple formula for improvement.

First, keep enforcement targeted and focused on suppliers, not just clerks. Warning letters clearly change behavior at the store level, but the biggest impact will come from auditing distributors and importers, and stopping bad shipments before they reach retail shelves.

Second, make compliance easy. A single-page list of authorized nicotine-pouch products—currently the twenty approved ZYN items—should be posted in every store and attached to distributor invoices. Point-of-sale systems can block barcodes for anything not on the list, and retailers could affirm, once a year, that they stock only approved items.

Third, widen the legal lane. The FDA launched a pilot program in September 2025 to speed review of new pouch applications. That program should spell out exactly what evidence is needed—chemical data, toxicology, nicotine release rates, and behavioral studies—and make timely decisions. If products like NOAT meet those standards, they should be authorized quickly. Legal competition among adult-oriented brands will crowd out the sketchy imports far faster than enforcement alone.

The Bottom Line

Enforcement matters, and the data show it works—where it happens. But the legal market is too narrow to protect consumers or encourage innovation. The current regime leaves a few ZYN products as lonely legal islands in a sea of gray-market pouches that range from sensible to reckless.

The FDA’s treatment of NOAT stands out as a case study in inconsistency: a quiet, adult-focused brand approved in Europe yet effectively banned in the US, while flashier and riskier options continue to slip through. That’s not a public-health victory; it’s a missed opportunity.

If the goal is to help adult smokers move to lower-risk products while keeping youth use low, the path forward is clear: enforce smartly, make compliance easy, and give good products a fair shot. Right now, we’re doing the first part well—but failing at the second and third. It’s time to fix that.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoOttawa Pretends To Pivot But Keeps Spending Like Trudeau

-

Business17 hours ago

Business17 hours agoCanada Hits the Brakes on Population

-

Crime6 hours ago

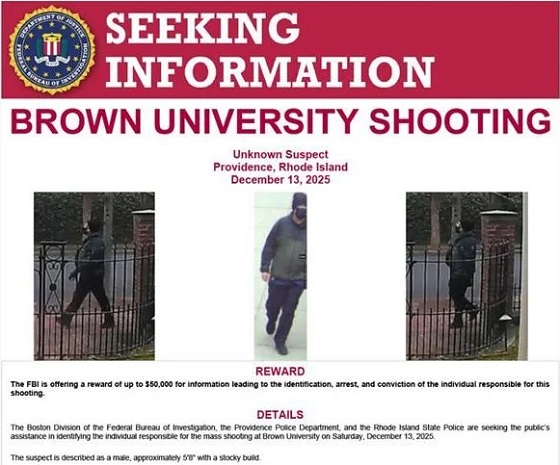

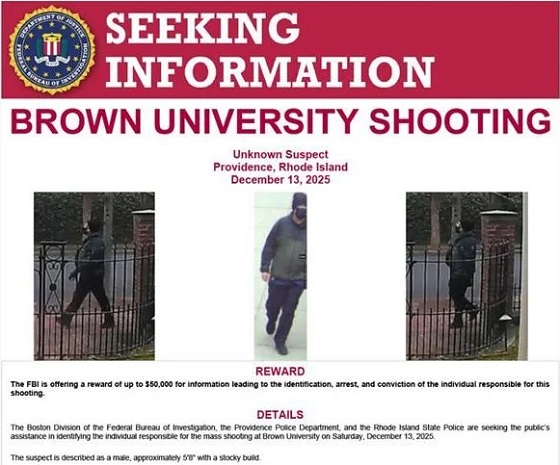

Crime6 hours agoBrown University shooter dead of apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoLiberals Twisted Themselves Into Pretzels Over Their Own Pipeline MOU

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoHow Wikipedia Got Captured: Leftist Editors & Foreign Influence On Internet’s Biggest Source of Info

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy20 hours ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy20 hours agoCanada Lets Child-Porn Offenders Off Easy While Targeting Bible Believers

-

International2 days ago

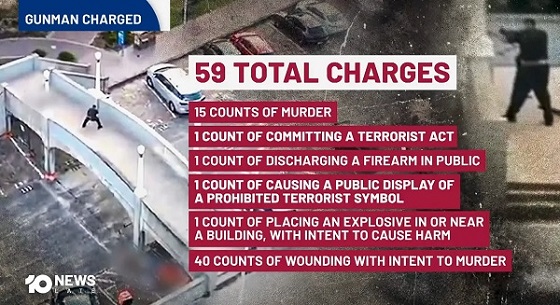

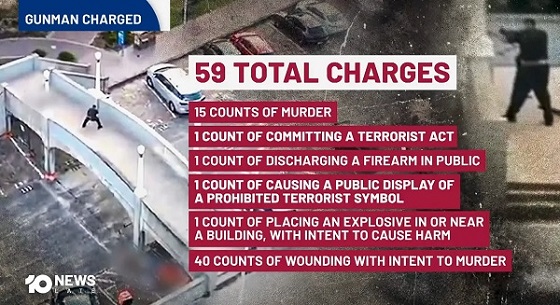

International2 days agoBondi Beach Shows Why Self-Defense Is a Vital Right

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoThe Uncomfortable Demographics of Islamist Bloodshed—and Why “Islamophobia” Deflection Increases the Threat