If you read the label “buffalo” on an elephant’s cage, don’t believe your eyes.

— Kozma Prutkov

It may be because the eyes of the world are focused on more disturbing and violent international affairs, but it’s still odd that so little attention is being paid to an issue happening in uncanny synchronicity among well over 100 countries. That issue is the development and implementation of central bank digital currency (CBDC), something holding the potential for economic and financial havoc.

The subject of CBDC might seem trivial for some people, complex and obscure for many others and dangerously clear for the rest. The triviality comes from thinking that our society has already embraced digital money in the form of credit cards, online banking, e-transfers, smartphone app payments and so on. Switching to something even more convenient and crypto-like-cool seems natural and desirable. For those less tech-savvy, the subject is complex, unnecessary and plain irritating. And then there are those – dismissed as “conspiracy theorists” by CBDC proponents – who see it as a tool of digital oppression that governments will impose on a naïve citizenry.

While not brand-new, the CBDC idea has gained significant momentum in the last three years. According to the Atlantic Council, a NATO-aligned think tank, 130 countries representing 98 percent of global GDP are exploring a CBDC, up from only 35 countries in May 2020. Such an explosion of interest surely means a significant need for this type of currency. Such a need, in turn, suggests that CBDC should be capable of doing something that conventional money can’t or is inefficient at. Since everyone uses money, those capabilities should be obvious to anyone regardless of his or her technical or financial knowledge.

Canada’s central bank, the Bank of Canada, announced its retail CBDC initiative (not to be confused with its wholesale counterpart) in February 2020, defining it like this: “Simply put, a digital Canadian dollar would be a digital form of the cash in your wallet. Like cash, it could buy the things you need. But the advantage is that you could also use it for online purchases and to transfer money between family and friends. And businesses could use it to pay each other.”

This definition is not helpful. It explains neither the characteristics of nor the need for CBDC. The envisioned digital Canadian dollar comes across as hardly different from a present-day bank account and your bank card, with which you can already buy things online and transfer money to family and friends.

If neither the distinctions from conventional currency nor the benefits are clear from the definition itself, then we should “look under the hood” of this CBDC phenomenon to see which of the three groups mentioned above has the strongest point.

Is CBDC Essentially Cash?

One thing the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) definition does make clear is that it sees CBDC as a like-for-like replacement for cash. The first of the two reasons announced for “building the capacity for cash-like CBDC” is as a contingency in case “the use of bank notes were to continue to decline to a point where Canadians no longer had the option of using them for a wide range of transactions.”

Canada is not alone in this; other countries exploring, piloting or using CBDC, from Cambodia to the United States, say the inevitable disappearance of cash is the major reason. “We aren’t using cash as much as we used to, and digital payments are becoming more and more common,” states the Bank of England, which held public consultations on CBDC this summer. Likewise the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), which declared that, “The first objective is to diversify the forms of cash provided to the public by the central bank, satisfy the public’s demand for digital cash and support financial inclusion.”

CBDC indeed shares some characteristics of cash. It would be issued and guaranteed by a central bank, whereas traditional bank deposits are held as liabilities by commercial banks, with government typically insuring them up to certain limits through deposit insurance programs. Like cash, CBDC by design does not and cannot incur interest, and one cannot have a savings or any kind of investment account with it (so-called “cash” accounts are not literal cash; the term signifies that the holdings are quickly convertible back to cash). There is also the “wallet” – a term widely used when describing the use and prerequisites for holding CBDC, which sounds like what we use for holding physical cash.

But are these characteristics, and the existence of CBDC wallets, enough to make the case for CBDC as a cash replacement?

Let’s consider a real-life scenario. While out fishing one day, you drop your (real) wallet containing (real) cash in Lake Ontario and it sinks from view. Unless you have a friend who’s a scuba diver, geared up and ready to do you a favour, your cash is gone. You can go to the BoC’s Ottawa headquarters and show them a full video recording of how much cash you had and how it got dropped in the water, but they still won’t print replacement banknotes and give them to you. But imagine you drop your phone and so goes your CBDC “wallet” application. As scary as the thought of losing a smartphone is, the app can be reinstalled on a new device and the digital “cash” fully recovered.

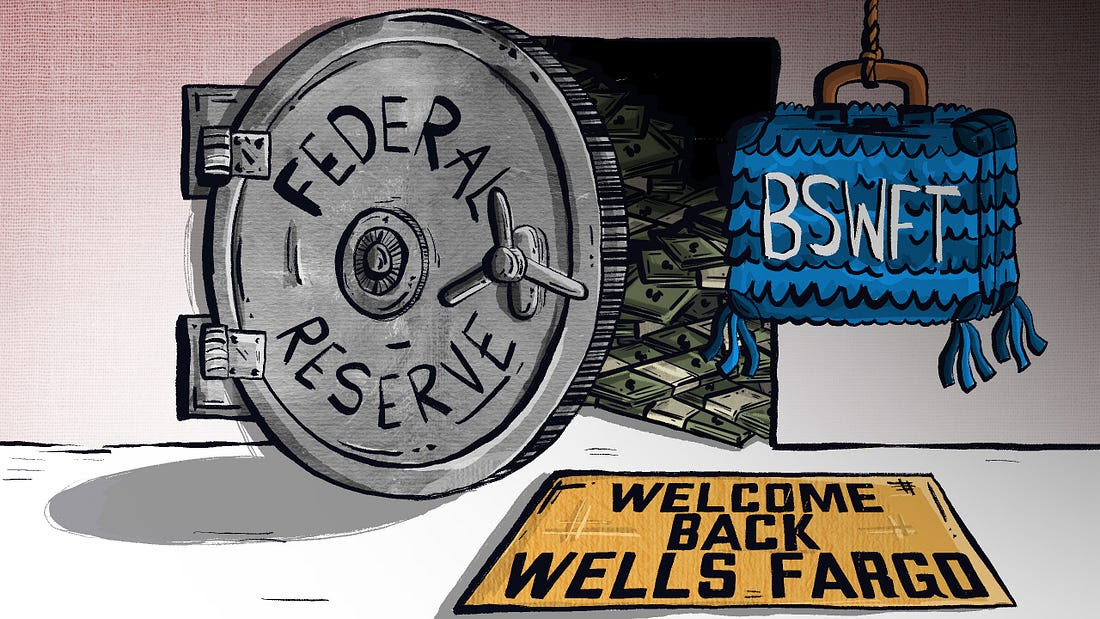

A better analogy than the CBDC “wallet,” then, is a purse that holds a key to your safe deposit box at a central bank vault, and to which the central bank has full access, including a duplicate key. The key is simply digitized. This again means the CBDC’s similarities are more with mobile app versions of your credit or debit card than with physical banknotes.

So if a CBDC is different from cash in that important regard, can it still compete with cash functionally from the perspective of what the tech world might call a “use case”?

Virtually all CBDC use case scenarios tout “financial inclusion” as a justification for pursuing the idea. “Financial inclusion” means tending to the so-called “underbanked,” people who for a number of reasons do not have access to (or do not want) bank accounts, including online banking and bank cards, and who resort to cash instead.

The Bank of Canada paper readily admits that CBDC cannot serve either of the two primary use cases. CBDC inherently lacks privacy as it is designed to always leave a digital trail, and its digital nature implies the use of an internet-connected mobile device, which hardly tends to the ‘technology averse.’

The BoC’s paper, Unmet Payment Needs and a Central Bank Digital Currency, updated in August, reveals its thinking on CBDC’s potential for increasing “financial inclusion.” It offers two major reasons why Canadians still use cash: 1) a preference for the privacy that cash provides, and 2) disliking or being uncomfortable using technology or lacking/unable to afford internet connectivity. (The bank claimed there was a third group of underbanked people, those who can’t afford a bank account, but this seemed odd as many financial institutions offer free bank accounts.)

The same paper readily admits that CBDC cannot serve either of the two primary use cases. CBDC inherently lacks privacy as it is designed to always leave a digital trail, and its digital nature implies the use of an internet-connected mobile device, which hardly tends to the “technology averse.”

The BoC also raises the question of what would happen if cash were to disappear and there was a power or telecommunication outage. “Without cash, a widely used offline method of payment available for any consumer segment would no longer exist, which could be especially important if a network or power outage occurred,” the paper notes. This implies unequivocally that cash is doomed but simultaneously fails to explain exactly why and makes the case (apparently unwittingly) for cash to remain. The BoC paper then mumbles wordily about the possible need for “digital payment innovations that can function offline,” such as peer-to-peer modes for making payments in CBDC during connectivity failure or power loss. But no amount of “digital payment innovations” (i.e., reinventing the financial bicycle) will resolve the problem of powering electronic devices during an extended blackout.

The BoC has also published a research note on using CBDC for offline payments to mimic physical notes and coins more realistically. But despite all this contemplation, among the following countries that have launched CBDC (in chronological order), so far none has implemented offline wallets: the Bahamas (Sand Dollar), Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (DCash), Nigeria (e-Naira), Jamaica (JamDex), China (eCNY), India (Digital Rupee), Russia (Digital Ruble). Among those, the Bank of Russia seems to be the only one that has announced an effort at developing an offline CBDC that would allow people to keep a limited amount in digital rubles available for payment in case of connectivity loss. “Offline” simply does not seem to be a priority, despite being probably the most relevant functionality for ensuring “financial inclusion.”

But even with the offline functionality available, CBDC does not look like cash and does not address the cash use cases – and this by the admission of those, like the BoC, who have prioritized cash replacement in implementing CBDC.

Nigeria’s Calamitous Experiment on 100 Million Citizens

The Bahamas’ Sand Dollar was the world’s first state-backed digital currency to be launched, its pilot program beginning in December 2019. The Sand Dollar’s value is tied to the Bahamian dollar which is, in turn, pegged to the U.S. dollar. Transactions with digital money are conducted through smartphone electronic wallets, and about 90 percent of the archipelago’s residents own smartphones. The regulator plans to issue new CBDC tokens as demand grows and concurrently phase out cash dollars to maintain market balance. This begs the question: is the CBDC filling in the gaps created by cash dying off naturally, or is the CBDC being artificially imposed in order to replace and bring about the demise of cash?

As to CBDC’s “financial inclusion” benefit, that should be most visible in jurisdictions with a large number of underbanked people. Are there any success stories in this regard? A good place to look is Nigeria, with a population of over 200 million, of whom about half did not have bank accounts when CBDC was implemented there.

Nigeria’s eNaira official launch ceremony, October 2021. (Source of photo: Bashir Ahmad, retrieved from Premium Times)

Nigeria’s eNaira official launch ceremony, October 2021. (Source of photo: Bashir Ahmad, retrieved from Premium Times)Nigeria’s CBDC, the eNaira, was officially launched in October 2021 and was the first serious test of CBDC implementation. With half of the population cash-dependent, the project’s primary stated goal was an “increase in financial inclusion.” After the first year, during which the eNaira was made available only to those with bank accounts, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) noted that, “The public adoption of the eNaira thus far has been disappointingly low.” How low? Only 0.8 percent of Nigerians with bank accounts downloaded eNaira wallets, of which most remained idle, not engaging in any transactions.

Despite that overwhelming indifference, in late 2022 the project went into its second phase, making eNaira available for the unbanked (but without any offline functionality), and last December Nigeria’s government launched an all-out attack on cash. The highest-denomination banknotes were demonetized, followed by the Central Bank of Nigeria announcing that by the end of January 2023 the country would fully transition to eNaira. People were required to transfer their cash holdings to the central bank, despite earlier assurances that physical cash would not be eliminated until CBDC was fully operational.

Despite the massive push on eNaira, many Nigerians remain confused about the very need for this government offering. While adoption is increasing, it is still driven entirely by artificially created cash shortages – not exactly as intended or at least advertised in the government’s claimed goal of ‘financial inclusion.’

As a result, the nation’s 100 million underbanked people were left with cancelled paper money they could no longer use to buy food or other necessities. This calamitous decision triggered violent riots with casualties as desperate hungry people took to the streets, demanding reinstatement of cash. The situation persisted for more than three months until Nigeria’s new president, Bola Ahmed Tinubu, restored the old currency’s validity, alongside a new naira (another story) and the eNaira.

It appears that the government in Abuja had no real appetite nor any good plan for this project. Its advisors from the World Economic Forum and IMF lacked a plan, too – offering only their strong support for digitization (as opposed to food or real money for starving Nigerians). Despite the massive push on eNaira, many Nigerians remain confused about the very need for this government offering. While adoption is increasing, it is still driven entirely by artificially created cash shortages – not exactly as intended or at least advertised in the government’s claimed goal of “financial inclusion.”

Calamitous imposition: In January, Nigeria announced the enforced elimination of cash under its eNaira CBDC transition, leaving the country’s 100 million “unbanked” people with no way to buy food or other necessities; hungry Nigerians rioted in the streets. Shown at top, people queueing at a cash machine in Yola; at bottom, angry protesters demolishing a commercial bank in Benin City. (Sources of photos: (top) AP Photo/Sunday Alamba; (bottom) Michael Egbejule, retrieved from The Guardian)

Calamitous imposition: In January, Nigeria announced the enforced elimination of cash under its eNaira CBDC transition, leaving the country’s 100 million “unbanked” people with no way to buy food or other necessities; hungry Nigerians rioted in the streets. Shown at top, people queueing at a cash machine in Yola; at bottom, angry protesters demolishing a commercial bank in Benin City. (Sources of photos: (top) AP Photo/Sunday Alamba; (bottom) Michael Egbejule, retrieved from The Guardian)To put the last nail in the coffin of the financial inclusion argument, consider what the IMF itself said in a recent Fintech Note. “Financial inclusion is a key policy objective that central banks, especially those in emerging and low-income countries, are considering for retail central bank digital currency (CBDC),” it wrote, and then concluded that, “The impact of CBDC for improving financial inclusion is currently speculative, where further evidence and experience are needed to fully understand benefits and limitations.”

How can the major reason for a large financial overhaul with many risks be…speculative, unless it is not the reason at all?

Is CBDC Effectively Crypto?

Another reason frequently cited for implementing CBDC is to counter the proliferation of cryptocurrency. “It’s also possible that private cryptocurrencies or central bank digital currencies issued by other countries could become widely used in Canada in the future,” said the BoC in its May news release announcing public consultation on the digital dollar. “This could compromise the role of an official, centrally issued currency – the Canadian dollar – in our economy and pose a risk to the stability of our financial system.” But how exactly CBDC is expected to counteract or adequately replace private crypto remains a mystery. Aside from both being digital, the two payment systems have completely different use cases and foundational principles.

Cryptocurrency was invented by an unknown person or group under the pseudonym Satoshi, who described it in a now-famous 2008 white paper as “an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust, allowing any two willing parties to transact directly with each other without the need for a trusted third party.” The concept of permissionless transactions became – and remains – the major defining characteristic and cornerstone for the first crypto, Bitcoin, and its hundreds of successors.

Even though the technological underpinning of CBDC and crypto can indeed be similar, CBDC is the conceptual opposite. It is a “permissioned” system as it is based on transactions being rendered trustworthy through the approval of a third party – i.e., a Central Bank. To provide permissionless consensus, cryptocurrency must rely upon cryptography-loaded and computationally heavy distributed ledger technology (DLT) (commonly known as blockchain), so far the only known effective technology for doing so. CBDC does not need to do this and China’s e-CNY, for example, does not.

Still, the comparisons with crypto keep creeping into discussion of CBDC, obfuscating such fundamental incompatibility. For example, Investopedia states that the U.S. Federal Reserve’s planned “digital fiat money will be similar to cryptocurrencies.”

Even some of the central banks claiming that digital currencies will counter crypto don’t, paradoxically, claim that CBDC and crypto are the same thing. “A digital Canadian dollar would not be a cryptocurrency, also known as a cryptoasset or private digital currency,” the BoC writes. Unlike with a CBDC, if you lose access to your crypto wallet, your crypto assets are lost forever. Confusingly, central banks describe CBDC as being somewhat like crypto, in that it’s digital, which ostensibly will make it a bulwark against those new players.

Central banks, curiously, frequently assert yet rarely actually enumerate the risks of crypto, besides referring to its volatile nature and the vulnerability of users to being fleeced by digital fraudsters – something which has always been the case for any speculative asset. In its January 2022 paper, Money and Payments: The U.S. Dollar in the Age of Digital Transformation, the U.S. Federal Reserve Board of Governors claims (but never substantiates why), “In our rapidly digitizing economy, the proliferation of private digital money could present risks to both individual users and the financial system as a whole. A U.S. CBDC could mitigate some of these risks while supporting private sector innovation.”

More and more it appears that a major motivator of central banks pushing CBDC is simply their fear of missing out (FOMO). FOMO can account for their chasing after innovation. If anyone is going to do digital currencies, they seem to be saying, it should be us. You can trust us and, besides, we need to build up our technological muscles. One certainly smells more than a whiff of FOMO in the BoC’s commitment, stated in 2020, to “build the capacity to issue a general purpose, cash-like CBDC should the need to implement one arise. Because it will take several years to build this capacity, the Bank cannot wait until the need is evident before launching preparatory work.”

In 2022, the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) stated that the main objective of CBDC – which it described as programmable digital money – is to provide a safe environment for innovation. In March 2022, the Biden Administration released a framework for the “responsible development of digital assets,” which included exploring the digital dollar in part due to the need for financial innovation. The Central Bank of Russia, too, defines staying competitive in financial markets, creating new financial products and developing new payment infrastructure as its reasons for CBDC.

‘If currency and payments are already digital, and central banks are not embracing technologies like blockchain, it begs the question of what, if anything, is truly new in CBDCs.’

Digital currency innovation usually deals with crypto’s aforementioned foundational technology, DLT or blockchain. The use of this computationally heavy, cryptography-based technology is not warranted or even desirable, however, in the case of “permissioned” CBDC. Indeed, the world’s CBDC leader, China, made no fuss about this in running its e-CNY (digital RMB). PBOC officials have confirmed that China’s CBDC does not use DLT because doing so would be unsuited to handling the anticipated volume of digital transactions.

In any event, a report presented as testimony to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission two years ago asserted that the U.S. financial elite’s FOMO vis-à-vis China may be misplaced. “China’s fintech success has been impressive, but it remains mostly a domestic affair,” wrote Martin Chorzempa from the Peter C. Peterson Institute for International Economics. “Its fintech giants Ant Group and Tencent have achieved enormous valuations, but their attempts to gain users internationally other than Chinese tourists abroad have so far made little inroads, and national security concerns in jurisdictions around the world mean that this is not likely to change anytime soon. Hype has far outpaced the reality in digital currencies, CBDCs, and China’s digital RMB in particular.” So China’s fintech success, while impressive, has nothing to do with CBDC. The report also states: “If currency and payments are already digital, and central banks are not embracing technologies like blockchain, it begs the question of what, if anything, is truly new in CBDCs.”

It begs the question, indeed.

What’s Unique about Central Bank Digital Currency?

If CBDC does not effectively close the gap for cash that allegedly is going extinct (or being pushed toward extinction), cannot serve the market needs fulfilled by cryptocurrencies, and does not constitute useful innovation in fintech, then what are the defining features that can give us clues about why it might be thought necessary?

CBDC does have two other properties that do not draw due spotlight in the official justification papers and popular announcements, but do make it distinctly different from the money we use today. Those properties, however low-profile, are surely not there by accident. They are what give some observers (often dismissed as conspiracy theorists or the “looney tunes crowd”) cause for concern.

First, alluded to previously, is CBDC’s centrally monitored and controlled traceability. Unlike cash, CBDC offers no anonymity whatsoever, as every transaction is recorded centrally and is always attached to a person, business or organization. “Recorded centrally” is also an important distinction from the traceable private digital money used today, for which records are stored at a bank and are thus free from direct and immediate government oversight. And while the technical implementation of such recording may be done on a distributed infrastructure, control and transparency are always centralized.

Whether national populations are ready for full visibility of their transactions by their respective government is a big question. Not everyone likes it when his or her payments cease to be anonymous and confidential, and this is not necessarily about illegal operations or transactions. Some may not want their name to be associated with a purchase from, say, a sex shop, some may not want it known if they are transferring funds to one child and not another, and some may want to keep a visit to a private health care clinic private. Some may simply think it’s no one’s business but their own how they spend their money; their money is their property, to use and enjoy as they see fit.

Curiously enough, governments keep touting CBDC’s confidentiality and security by offering not to disclose data about transactions to other organizations (where, by contrast, banks do often abuse and sell such information to merchants for targeted advertisement, for example). But that’s just another way of saying that a CBDC user’s “anonymity” is under the full control of the government and the government decides what gets disclosed, to whom and when.

The architects of China’s e-CNY even coined the euphemism “controllable anonymity” to obscure their CBDC’s obvious and innate absence of anonymity. Explanations from PBOC officials as well as the established usage of “controllable” in Chinese technology policy discourse make it clear that “controllable” means controlled by a central authority rather than an individual.

Nonsense, the bank asserted: ‘You will be able to spend your digital rubles as you see fit.’ But then Interfax in September reported that marking digital rubles so they can only be used for specific purposes would be explored by the Bank of Russia.

Some CBDC architects have foregone soothing assurances or ludicrous euphemisms for brusque honesty. Ivan Zimin, Director of the Financial Technologies Department of the Bank of Russia, puts it this way: “Anonymity will be incomplete in any case, unlike cash, which the digital ruble is an analogue of. The digital ruble will be issued and circulated on the Central Bank’s platform. Each digital ruble will have its own unique code, which will allow tracking its lifecycle. For example, this will allow the government to verify that the funds allocated under government contracts, programs, or subsidies are not used for other purposes.”

Zimin’s bracing clarity brings us to the second unique feature of CBDC: centrally controlled traceability will facilitate many ways for a government to not only see but influence where this alleged “cash replacement” goes and how it is used. A closer look at Zimin’s statement reveals another important characteristic of the digital ruble – programmability. The ability to make CBDC “smart” is unequivocally present in all of its current implementations. The unique code of each digital ruble, states one Russian bank in its CBDC explainer, “Allows tracing and even its programming for certain actions, similar to what cryptocurrencies can do.”

This revelation seems to have caused some embarrassment. In April, the Bank of Russia published an FAQ (in Russian) about its digital token, which included debunking “myths about the digital ruble.” One of these was that “digital rubles can only be spent on a limited list of goods.” Nonsense, the bank asserted: “You will be able to spend your digital rubles as you see fit.” But then Interfax in September reported (in Russian) that marking digital rubles so they can only be used for specific purposes would be explored by the Bank of Russia. “This opportunity will be considered at later stages of promoting the digital ruble,” the central bank’s deputy chairman, Alexey Zabotkin, told reporters.

At the end of the day, the debate about what CBDC design is the best and most risk-free is moot because such design can be changed by the designer as long as the technology allows it. And it does, and the designer (i.e., government) knows it and seems willing to change its mind as progress is made.

Does the Looney-Tunes Crowd have a Point?

Centrally controlled traceability and programmability are CBDC’s two defining (as opposed to claimed) characteristics. These could very well have useful applications: reduction of crime and tax evasion; elimination of counterparty risk with commercial banks which, in turn, would increase the financial system’s security and stability; implementing efficient policies by bypassing intermediaries and directly targeting sectors or groups (such as parents with children); manipulating currency value to manage economic instability, stimulate growth or support certain industries; or implement negative interest rates on cash holdings and thus reduce money in circulation.

Patrick Schueffel, writing in the Journal of Digital Assets, provides an excellent overview of these kinds of CBDC advantages in a happy utopian society under wise, benevolent and altruistic government. According to Fabio Panetta, a member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank (ECB), which is also actively working on a digital euro, “Central bank money is a risk-free form of money that is guaranteed by the State: by its strength, its credibility, its authority.” (Emphasis added.) This is the foundational premise of any argument in favour of fully traceable and programmable CBDC.

The problem is that wise, benevolent and altruistic government has been hard to come by throughout history. Recent examples of Western democratic governments forcing political compliance by attacking dissidents’ bank accounts serve as a reminder of today’s state of affairs (as also discussed in this recent C2Cessay). Indeed, Schueffel also warns about a worrying number of other, not-so-welcome CBDC “special purposes”: spending caps or blocks on individuals or organizations; transfer limits; foreign exchange limits; capital export/foreign asset purchase controls; consumption controls; penalty taxes; forced loans (the government, for example, borrowing money from you arbitrarily); nudge economics; geo fencing; and curfew enforcement (such as by imposing automatic fines for violations). Those utterly undemocratic and, indeed, tyrannical purposes should outrage any Westerner, but they fit China’s social credit system like a glove.

And those are just the dangers of abuse in the perfect implementation scenario. But CBDC also bears the risks of destabilizing the financial system by disintermediating fiscal transactions from commercial banks and eroding the established banking system, which could lead to a financial crisis. And as with any other information system, CBDCs will be like catnip to hackers. CBDCs will be especially vulnerable due to their centralized nature, which could lead to counterfeiting of money, theft or disruption of the whole financial system. With foreign governments joining the “hackathon,” CBDCs will become another front in the expanding theatre of “hybrid warfare,” bringing such attacks to a whole new level for espionage and to destabilize the target country’s entire economy.

The UK’s House of Commons economic affairs committee’s paper, Central bank digital currencies: A solution in search of a problem? flagged many concerns about a retail CBDC. Among them: “To what problem is a CBDC the answer?”, “How can a CBDC be a competitive payments option without causing a level of banking sector disintermediation that would have negative consequences for credit allocation and financial stability?”, “How can a CBDC ensure strong privacy safeguards while also meeting financial compliance rules?”, and “Which organisations will be able to access sensitive CBDC payments data, and for what purpose will that data be used?”

Just this month came new evidence of the creep toward this troubling future. The European Parliament and member states came to a provisional agreement to establish an “EU Digital Identity Wallet.” Issued by member states, on a voluntary basis to start, it will hold digital identification and personal information, from drivers’ licences and educational diplomas to medical records and banking information. The EU touts is as a secure way for people to prove their identity and share electronic documents with a tap on a smartphone icon. Robert Roos, a Dutch Member of the European Parliament, quoted EU Commissioner Thierry Breton as saying: “Now that we have a Digital Identity Wallet, we have to put something in it.” Roos helpfully explained: “What he meant is the digital euro, also known as a CBDC,” clearly indicating where the effort is headed.

If the traceable and programmable nature of CBDC – plus its entwinement with other intrusive, privacy-killing measures like digital identification – is hushed while virtue-signalling but meaningless “financial inclusion” and questionable innovation motives are publicly advertised instead, then it’s little surprise that the “looney tunes crowd” has reached this conclusion: full adoption of CBDC, especially if accompanied by elimination of cash and any alternative trust-less, permission-less, decentralized monetary systems like cryptocurrency, would close the loop of digitized surveillance with integrated incentives/punishments and AI-enabled automation for ensuring “the right” behaviour of the citizens. Humanity would face a dystopian future of a sort not imagined even by Orwell or Huxley.

What about Canada?

In Ontario most community centres have gone annoyingly cashless. It was done under the pretext of the Covid-19 pandemic and has never been reversed; similar things have occurred in other organizations and some private businesses. Governments so concerned about “financial inclusion” seem to be busy generating inclusion gaps themselves. Who’s going to bet that once the Canadian e-dollar becomes available it will be made immediately acceptable at those community centres and celebrated as a gap getting closed?

The Bank of Canada’s cognitive conversation is backwards: instead of looking for a justifiable use case, it goes into talk of ‘overcoming the barriers’ – and not technical barriers, mind you, but the absence of popular desire or substantive need for a CBDC at all.

Unlike in Nigeria, where about half of adults have no bank account, only 2 percent of Canadians still rely heavily on cash. Would Canadian governments be as “lenient” as Nigeria in tolerating such a small group when introducing a CBDC? We can take many hints already from the governments’ past attitudes toward “fringe minorities,” unvaccinated truckers or nurses, and common-sense voices in general, but one specific example stands out. The BoC’s August 2023 paper, Unmet Payment Needs and a Central Bank Digital Currency, admits there’s an apparent lack of need for CBDC among Canadians. “As a practical matter, achieving wide adoption, acceptance and use of CBDC could be challenging because most Canadians have access to several methods of payment using commercial bank money, provided by sophisticated incumbents,” the paper states. “Overcoming such barriers could require significant and sustained investment by the central bank.”

The BoC’s cognitive conversation is backwards: instead of looking for a justifiable use case, it goes into talk of “overcoming the barriers” – and not technical barriers, mind you, but the absence of popular desire or substantive need for a CBDC at all. This is because the BoC already announced its commitment in February 2020 to “build the capacity to issue a general purpose, cash-like CBDC,” reaffirming its commitment in May of this year and launching an online public consultation on the features “Canadians want” from a digital Canadian dollar. The consultation closed in just five weeks, and its results are yet to be published. We can only speculate why.

So, like Nigerians, although with a much smaller “financial inclusion” gap to close, Canadians have expressed no desire, understanding or even, for the most part, awareness of the headlong rush towards imposing a CBDC. And as in Nigeria, the nation’s central bank does not listen but simply insists on and proceeds with this compulsive love affair, claiming that it is to benefit Canadians but failing or not even trying to articulate how.

Gleb Lisikh is a researcher and IT management professional, and a father of three children. He lives in Vaughan, Ontario and grew up in various parts of the Soviet Union.