From The Center Square

A judge appointed to the bench by former President Donald Trump rejected calls from the man accused of trying to assassinate Trump in September for a new judge in the case.

U.S. Judge Aileen Cannon said in an order Tuesday that she saw “no proper basis for recusal.”

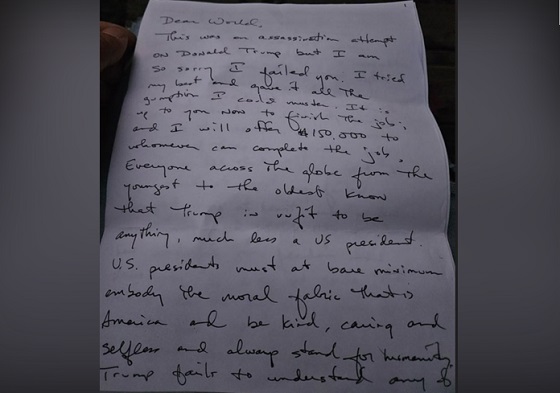

Prosecutors charged Ryan Wesley Routh, 58, of Hawaii, with possession of a firearm by a felon, possession of a firearm with an obliterated serial number, and attempted assassination of a major presidential candidate. Secret Service agents said Routh built a sniper’s nest on the sixth hole of the Trump International Golf Club West Palm Beach. Prosecutors accused Routh of stalking Trump for a month before that. Routh has pleaded not guilty.

Routh’s defense team wants a new judge on the case because of Cannon’s past work on Trump’s classified documents criminal complaint. Routh said if Trump were reelected on Nov. 5 to the White House, he would be in a position to offer Cannon a better federal job. The team also said some people have questioned how the case got in front of Cannon. They also noted that Cannon had attended high school with one of the prosecutors on the case and attended his wedding nine years ago while serving as an Assistant United States Attorney.

“After all, the facts here are unprecedented,” the defense wrote in a reply to prosecutor’s opposition to the recusal. “To briefly recap: a former President, Mr. Trump, is the alleged victim in this criminal case; Mr. Trump appointed Your Honor to the federal bench; this Court previously presided over cases where Mr. Trump was a party and issued some rulings that were favorable to him, including one dismissing a criminal case against him; while on the campaign trail, Mr. Trump has repeatedly and publicly praised this Court and its rulings; Mr. Trump would have authority to appoint Your Honor to a position of power were he to become President again; and given the low odds of this Court being assigned three cases involving Mr. Trump, some have questioned whether the cases have been assigned at random.”

Prosecutors opposed the recusal motion.

Cannon said she has no relationship with Trump.

“I have never spoken to or met former President Trump except in connection with his required presence at an official judicial proceeding, through counsel,” she wrote in the order.

Cannon also said she had no control over what Trump says about her or her rulings. Trump praised her decision to dismiss the classified documents case.

In July, Cannon dismissed the 40 felonies Trump faced in the classified documents-related criminal case because she said the appointment of Special Counsel Jack Smith violated the Constitution. Smith has appealed that decision. Legal experts widely considered the classified documents case as Trump’s most challenging legal hurdle.

Cannon also shot back at claims from the defense that the case might not have been randomly assigned to her.

“This case, like the prior cited cases involving former President Trump, were randomly assigned to me through the Clerk’s random case assignment system. Period. I will not be guided by highly inaccurate, uninformed, or speculative opinions to the contrary,” she wrote.

Cannon also said her professional friendship with a former colleague didn’t pass the recusal test.

“I maintain no ongoing personal relationship with the prosecutor, nor have I communicated with him in years,” she wrote. “In short, my personal friendship years ago with the prosecutor has no bearing or influence whatsoever on my impartial handling of this case or any other case in which he may appear as counsel of record.”