Economy

Federal government’s GHG reduction plan will impose massive costs on Canadians

From the Fraser Institute

Many Canadians are unhappy about the carbon tax. Proponents argue it’s the cheapest way to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which is true, but the problem for the government is that even as the tax hits the upper limit of what people are willing to pay, emissions haven’t fallen nearly enough to meet the federal target of at least 40 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. Indeed, since the temporary 2020 COVID-era drop, national GHG emissions have been rising, in part due to rapid population growth.

The carbon tax, however, is only part of the federal GHG plan. In a new study published by the Fraser Institute, I present a detailed discussion of the Trudeau government’s proposed Emission Reduction Plan (ERP), including its economic impacts and the likely GHG reduction effects. The bottom line is that the package as a whole is so harmful to the economy it’s unlikely to be implemented, and it still wouldn’t reach the GHG goal even if it were.

Simply put, the government has failed to provide a detailed economic assessment of its ERP, offering instead only a superficial and flawed rationale that overstates the benefits and waives away the costs. My study presents a comprehensive analysis of the proposed policy package and uses a peer-reviewed macroeconomic model to estimate its economic and environmental effects.

The Emissions Reduction Plan can be broken down into three components: the carbon tax, the Clean Fuels Regulation (CFR) and the regulatory measures. The latter category includes a long list including the electric vehicle mandate, carbon capture system tax credits, restrictions on fertilizer use in agriculture, methane reduction targets and an overall emissions cap in the oil and gas industry, new emission limits for the electricity sector, new building and motor vehicle energy efficiency mandates and many other such instruments. The regulatory measures tend to have high upfront costs and limited short-term effects so they carry relatively high marginal costs of emission reductions.

The cheapest part of the package is the carbon tax. I estimate it will get 2030 emissions down by about 18 per cent compared to where they otherwise would be, returning them approximately to 2020 levels. The CFR brings them down a further 6 per cent relative to their base case levels and the regulatory measures bring them down another 2.5 per cent, for a cumulative reduction of 26.5 per cent below the base case 2030 level, which is just under 60 per cent of the way to the government’s target.

However, the costs of the various components are not the same.

The carbon tax reduces emissions at an initial average cost of about $290 per tonne, falling to just under $230 per tonne by 2030. This is on par with the federal government’s estimate of the social costs of GHG emissions, which rise from about $250 to $290 per tonne over the present decade. While I argue that these social cost estimates are exaggerated, even if we take them at face value, they imply that while the carbon tax policy passes a cost-benefit test the rest of the ERP does not because the per-tonne abatement costs are much higher. The CFR roughly doubles the cost per tonne of GHG reductions; adding in the regulatory measures approximately triples them.

The economic impacts are easiest to understand by translating these costs into per-worker terms. I estimate that the annual cost per worker of the carbon-pricing system net of rebates, accounting for indirect effects such as higher consumer costs and lower real wages, works out to $1,302 as of 2030. Adding in the government’s Clean Fuels Regulations more than doubles that to $3,550 and adding in the other regulatory measures increases it further to $6,700.

The policy package also reduces total employment. The carbon tax results in an estimated 57,000 fewer jobs as of 2030, the Clean Fuels Regulation increases job losses to 94,000 and the regulatory measures increases losses to 164,000 jobs. Claims by the federal government that the ERP presents new opportunities for jobs and employment in Canada are unsupported by proper analysis.

The regional impacts vary. While the energy-producing provinces (especially Alberta, Saskatchewan and New Brunswick) fare poorly, Ontario ends up bearing the largest relative costs. Ontario is a large energy user, and the CFR and other regulatory measures have strongly negative impacts on Ontario’s manufacturing base and consumer wellbeing.

Canada’s stagnant income and output levels are matters of serious policy concern. The Trudeau government has signalled it wants to fix this, but its climate plan will make the situation worse. Unfortunately, rather than seeking a proper mandate for the ERP by giving the public an honest account of the costs, the government has instead offered vague and unsupported claims that the decarbonization agenda will benefit the economy. This is untrue. And as the real costs become more and more apparent, I think it unlikely Canadians will tolerate the plan’s continued implementation.

Author:

Alberta

Federal budget: It’s not easy being green

From Resource Works

Canada’s climate rethink signals shift from green idealism to pragmatic prosperity.

Bill Gates raised some eyebrows last week – and probably the blood pressure of climate activists – when he published a memo calling for a “strategic pivot” on climate change.

In his memo, the Microsoft founder, whose philanthropy and impact investments have focused heavily on fighting climate change, argues that, while global warming is still a long-term threat to humanity, it’s not the only one.

There are other, more urgent challenges, like poverty and disease, that also need attention, he argues, and that the solution to climate change is technology and innovation, not unaffordable and unachievable near-term net zero policies.

“Unfortunately, the doomsday outlook is causing much of the climate community to focus too much on near-term emissions goals, and it’s diverting resources from the most effective things we should be doing to improve life in a warming world,” he writes.

Gates’ memo is timely, given that world leaders are currently gathered in Brazil for the COP30 climate summit. Canada may not be the only country reconsidering things like energy policy and near-term net zero targets, if only because they are unrealistic and unaffordable.

It could give some cover for Canadian COP30 delegates, who will be at Brazil summit at a time when Prime Minister Mark Carney is renegotiating his predecessor’s platinum climate action plan for a silver one – a plan that contains fewer carbon taxes and more fossil fuels.

It is telling that Carney is not at COP30 this week, but rather holding a summit with Alberta Premier Danielle Smith.

The federal budget handed down last week contains kernels of the Carney government’s new Climate Competitiveness Strategy. It places greater emphasis on industrial strategy, investment, energy and resource development, including critical minerals mining and LNG.

Despite his Davos credentials, Carney is clearly alive to the fact it’s a different ballgame now. Canada cannot afford a hyper-focus on net zero and the green economy. It’s going to need some high octane fuel – oil, natural gas and mining – to prime Canada’s stuttering economic engine.

The prosperity promised from the green economy has not quite lived up to its billing, as a recent Fraser Institute study reveals.

Spending and tax incentives totaling $150 billion over a decade by Ottawa, B.C, Ontario, Alberta and Quebec created a meagre 68,000 jobs, the report found.

“It’s simply not big enough to make a huge difference to the overall performance of the economy,” said Jock Finlayson, chief economist for the Independent Contractors and Business Association and co-author of the report.

“If they want to turn around what I would describe as a moribund Canadian economy…they’re not going to be successful if they focus on these clean, green industries because they’re just not big enough.”

There are tentative moves in the federal budget and Climate Competitiveness Strategy to recalibrate Canada’s climate action policies, though the strategy is still very much in draft form.

Carney’s budget acknowledges that the world has changed, thanks to deglobalization and trade strife with the U.S.

“Industrial policy, once seen as secondary to market forces, is returning to the forefront,” the budget states.

Last week’s budget signals a shift from regulations towards more investment-based measures.

These measures aim to “catalyse” $500 billion in investment over five years through “strengthened industrial carbon pricing, a streamlined regulatory environment and aggressive tax incentives.”

There is, as-yet, no commitment to improve the investment landscape for Alberta’s oil industry with the three reforms that Alberta has called for: scrapping Bill C-69, a looming oil and gas emissions cap and a West Coast oil tanker moratorium, which is needed if Alberta is to get a new oil pipeline to the West Coast.

“I do think, if the Carney government is serious about Canada’s role, potentially, as an global energy superpower, and trying to increase our exports of all types of energy to offshore markets, they’re going to have to revisit those three policy files,” Finlayson said.

Heather Exner-Pirot, director of energy, natural resources and environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, said she thinks the emissions cap at least will be scrapped.

“The markets don’t lie,” she said, pointing to a post-budget boost to major Canadian energy stocks. “The energy index got a boost. The markets liked it. I don’t think the markets think there is going to be an emissions cap.”

Some key measures in the budget for unlocking investments in energy, mining and decarbonization include:

- incentives to leverage $1 trillion in investment over the next five years in nuclear and wind power, energy storage and grid infrastructure;

- an expansion of critical minerals eligible for a 30% clean technology manufacturing investment tax credit;

- $2 billion over five years to accelerate critical mineral production;

- tax credits for turquoise hydrogen (i.e. hydrogen made from natural gas through methane pyrolysis); and

- an extension of an investment tax credit for carbon capture utilization and storage through to 2035.

As for carbon taxes, the budget promises “strengthened industrial carbon pricing.”

This might suggest the government’s plan is to simply simply shift the burden for carbon pricing from the consumer entirely onto industry. If that’s the case, it could put Canadian resource industries at a disadvantage.

“How do we keep pushing up the carbon price — which means the price of energy — for these industries at a time when the United States has no carbon pricing at all?” Finlayson wonders.

Overall, Carney does seem to be moving in the right direction in terms of realigning Canada’s energy and climate policies.

“I think this version of a Liberal government is going to be more focused on investment and competitiveness and less focused around the virtue-signaling on climate change, even though Carney personally has a reputation as somebody who cares a lot about climate change,” Finlayson said.

“It’s an awkward dance for them. I think they are trying to set out a different direction relative to the Trudeau years, but they’re still trying to hold on to the Trudeau climate narrative.”

Pictured is Mark Carney at COP26 as UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance. He is not at COP30 this week. UNRIC/Miranda Alexander-Webber

Resource Works News

Business

Carney government needs stronger ‘fiscal anchors’ and greater accountability

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill and Grady Munro

Following the recent release of the Carney government’s first budget, Fitch Ratings (one of the big three global credit rating agencies) issued a warning that the “persistent fiscal expansion” outlined in the budget—characterized by high levels of spending, borrowing and debt accumulation—will erode the health of Canada’s finances and could lead to a downgrade in Canada’s credit rating.

Here’s why this matters. Canada’s credit rating impacts the federal government’s cost of borrowing money. If the government’s rating gets downgraded—meaning Canadian federal debt is viewed as an increasingly risky investment due to fiscal mismanagement—it will likely become more expensive for the government to borrow money, which ultimately costs taxpayers.

The cost of borrowing (i.e. the interest paid on government debt) is a significant part of the overall budget. This year, the federal government will spend a projected $55.6 billion on debt interest, which is more than one in every 10 dollars of federal revenue, and more than the government will spend on health-care transfers to the provinces. By 2029/30, interest costs will rise to a projected $76.1 billion or more than one in every eight dollars of revenue. That’s taxpayer money unavailable for programs and services.

Again, if Canada’s credit rating gets downgraded, these costs will grow even larger.

To maintain a good credit rating, the government must prevent the deterioration of its finances. To do this, governments establish and follow “fiscal anchors,” which are fiscal guardrails meant to guide decisions regarding spending, taxes and borrowing.

Effective fiscal anchors ensure governments manage their finances so the debt burden remains sustainable for future generations. Anchors should be easily understood and broadly applied so that government cannot get creative with its accounting to only technically abide by the rule, but still give the government the flexibility to respond to changing circumstances. For example, a commonly-used rule by many countries (including Canada in the past) is a ceiling/target for debt as a share of the economy.

The Carney government’s budget establishes two new fiscal anchors: balancing the federal operating budget (which includes spending on day-to-day operations such as government employee compensation) by 2028/29, and maintaining a declining deficit-to-GDP ratio over the years to come, which means gradually reducing the size of the deficit relative to the economy. Unfortunately, these anchors will fail to keep federal finances from deteriorating.

For instance, the government’s plan to balance the “operating budget” is an example of creative accounting that won’t stop the government from borrowing money each year. Simply put, the government plans to split spending into two categories: “operating spending” and “capital investment” —which includes any spending or tax expenditures (e.g. credits and deductions) that relates to the production of an asset (e.g. machinery and equipment)—and will only balance operating spending against revenues. As a result, when the government balances its operating budget in 2028/29, it will still incur a projected deficit of $57.9 billion when spending on capital is included.

Similarly, the government’s plan to reduce the size of the annual deficit relative to the economy each year does little to prevent debt accumulation. This year’s deficit is expected to equal 2.5 per cent of the overall economy—which, since 2000, is the largest deficit (as a share of the economy) outside of those run during the 2008/09 financial crisis and the pandemic. By measuring its progress off of this inflated baseline, the government will technically abide by its anchor even as it runs relatively large deficits each and every year.

Moreover, according to the budget, total federal debt will grow faster than the economy, rising from a projected 73.9 per cent of GDP in 2025/26 to 79.0 per cent by 2029/30, reaching a staggering $2.9 trillion that year. Simply put, even the government’s own fiscal plan shows that its fiscal anchors are unable to prevent an unsustainable rise in government debt. And that’s assuming the government can even stick to these anchors—which, according to a new report by the Parliamentary Budget Officer, is highly unlikely.

Unfortunately, a federal government that can’t stick to its own fiscal anchors is nothing new. The Trudeau government made a habit of abandoning its fiscal anchors whenever the going got tough. Indeed, Fitch Ratings highlighted this poor track record as yet another reason to expect federal finances to continue deteriorating, and why a credit downgrade may be on the horizon. Again, should that happen, Canadian taxpayers will pay the price.

Much is riding on the Carney government’s ability to restore Canada’s credibility as a responsible fiscal manager. To do this, it must implement stronger fiscal rules than those presented in the budget, and remain accountable to those rules even when it’s challenging.

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days agoRichmond Mayor Warns Property Owners That The Cowichan Case Puts Their Titles At Risk

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSluggish homebuilding will have far-reaching effects on Canada’s economy

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoMark Carney Seeks to Replace Fiscal Watchdog with Loyal Lapdog

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoBondi and Patel deliver explosive “Clinton Corruption Files” to Congress

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoUS announces Operation Southern Spear, targeting narco-terrorists

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoEU’s “Democracy Shield” Centralizes Control Over Online Speech

-

Business2 days ago

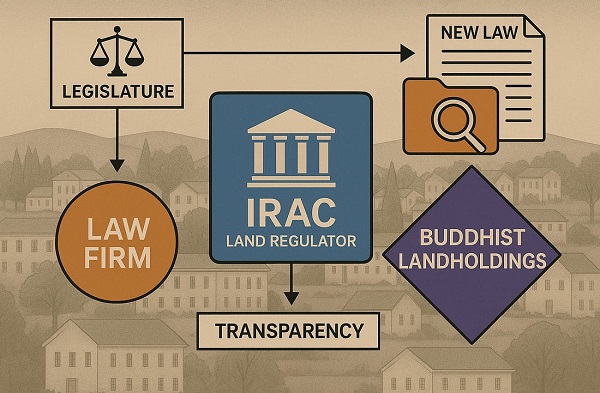

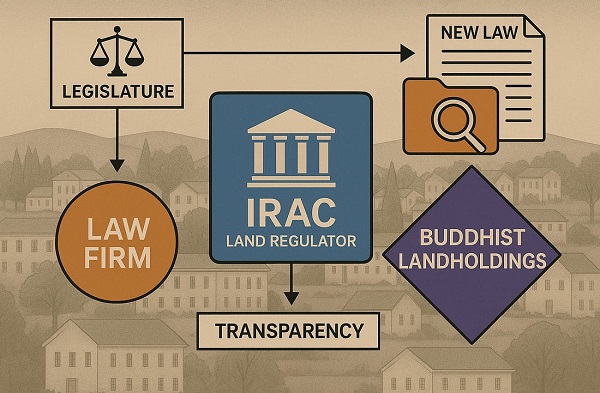

Business2 days agoP.E.I. Moves to Open IRAC Files, Forcing Land Regulator to Publish Reports After The Bureau’s Investigation

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoMajor new studies link COVID shots to kidney disease, respiratory problems