Fraser Institute

Federal government’s fiscal record—one for the history books

From the Fraser Institute

By Jake Fuss and Grady Munro

Per-person federal spending is expected to equal $11,901 this year. To put this into perspective, this is significantly more than Ottawa spent during the global financial crisis in 2008 or either world war.

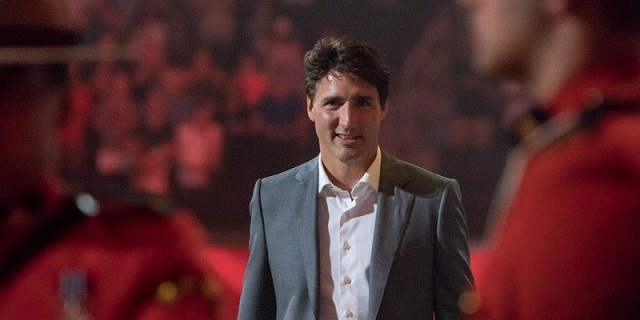

The Trudeau government tabled its 2024 budget earlier this month and the contents of the fiscal plan laid bare the alarming state of federal finances. Both spending and debt per person are at or near record highs and prospects for the future don’t appear any brighter.

In the budget, the Trudeau government outlined plans for federal finances over the next five years. Annual program spending (total spending minus debt interest costs) will reach a projected $483. billion in 2024/25, $498.7 billion in 2025/26, and continue growing in the years following. By 2028/29 the government plans to spend $542.0 billion on programs—an 18.4 per cent increase from current levels.

This is not a new or surprising development for federal finances. Since taking office in 2015, the Trudeau government has shown a proclivity to spend at nearly every turn. Prime Minister Trudeau has already recorded the five highest levels of federal program spending per person (adjusted for inflation) in Canadian history from 2018 to 2022. Projections for spending in the 2024 budget assert the prime minister is now on track to have the eight highest years of per-person spending on record by the end of the 2025/26 fiscal year.

Per-person federal spending is expected to equal $11,901 this year. To put this into perspective, this is significantly more than Ottawa spent during the global financial crisis in 2008 or either world war. It’s also about 28.0 per cent higher than the full final year of Stephen Harper’s time as prime minister, meaning the size of the federal government has expanded by more than one quarter in a decade.

The government has chosen to borrow substantial sums of money to fund a lot of this marked growth in spending. Federal debt under the Trudeau government has risen before, during and after COVID regardless of whether the economy is performing relatively well or comparatively poor. Between 2015 and 2024, Ottawa is expected to run 10 consecutive deficits, with total gross debt set to reach $2.1 trillion within the next 12 months.

The scale of recent debt accumulation is eye-popping even after accounting for a growing population and the relatively high inflation of the past two years. By the end of the current fiscal year, each Canadian will be burdened with $12,769 more in total federal debt (adjusted for inflation) than they were in 2014/15.

You can attribute some of this increase in borrowing to the effects of COVID, but debt had already grown by $2,954 per person from 2014 to 2019—before the pandemic. Moreover, budget estimates show gross debt per person (adjusted for inflation) is expected to rise by more than $2,500 by 2028/29.

As with spending, the Trudeau government is on track to record the six highest years of federal debt per-person (adjusted for inflation) in Canadian history between 2020/21 and the end of its term next autumn. Why should Canadians care about this record debt?

Simply put, rising debt leads to higher interest payments that current and future generations of taxpayers must pay—leaving less money for important priorities such as health care and social services. Moreover, all this spending and debt hasn’t helped improve living standards for Canadians. Canada’s GDP per person—a broad measure of incomes—was lower at the end of 2023 than it was nearly a decade ago in 2014.

The Trudeau government’s track record with federal finances is one for the history books. Ottawa’s spending continues to be at near-record levels and Canadians have never been burdened with more debt. Those aren’t the type of records we should strive to achieve.

Authors:

Business

Residents in economically free states reap the rewards

From the Fraser Institute

A report published by the Fraser Institute reaffirms just how much more economically free some states are compared with others. These are places where citizens are allowed to make more of their economic choices. Their taxes are lighter, and their regulatory burdens are easier. The benefits for workers, consumers and businesses have been clear for a long time.

There’s another group of states to watch: “movers” that have become much freer in recent decades. These are states that may not be the freest, but they have been cutting taxes and red tape enough to make a big difference.

How do they fare?

I recently explored this question using 22 years of data from the same Economic Freedom of North America index. The index uses 10 variables encompassing government spending, taxation and labour regulation to assess the degree of economic freedom in each of the 50 states.

Some states, such as New Hampshire, have long topped the list. It’s been in the top five for three decades. With little room to grow, the Granite State’s level of economic freedom hasn’t budged much lately. Others, such as Alaska, have significantly improved economic freedom over the last two decades. Because it started so low, it remains relatively unfree at 43rd out of 50.

Three states—North Carolina, North Dakota and Idaho—have managed to markedly increase and rank highly on economic freedom.

In 2000, North Carolina was the 19th most economically free state in the union. Though its labour market was relatively unhindered by the state’s government, its top marginal income tax rate was America’s ninth-highest, and it spent more money than most states.

From 2013 to 2022, North Carolina reduced its top marginal income tax rate from 7.75 per cent to 4.99 per cent, reduced government employment and allowed the minimum wage to fall relative to per-capita income. By 2022, it had the second-freest labour market in the country and was ninth in overall economic freedom.

North Dakota took a similar path, reducing its 5.54 per cent top income tax rate to 2.9 per cent, scaling back government employment, and lowering its minimum wage to better reflect local incomes. It went from the 27th most economically free state in the union in 2000 to the 10th freest by 2022.

Idaho saw the most significant improvement. The Gem State has steadily improved spending, taxing and labour market freedom, allowing it to rise from the 28th most economically free state in 2000 to the eighth freest in 2022.

We can contrast these three states with a group that has achieved equal and opposite distinction: California, Delaware, New Jersey and Maryland have managed to decrease economic freedom and end up among the least free overall.

What was the result?

The economies of the three liberating states have enjoyed almost twice as much economic growth. Controlling for inflation, North Carolina, North Dakota and Idaho grew an average of 41 per cent since 2010. The four repressors grew by just 24 per cent.

Among liberators, statewide personal income grew 47 per cent from 2010 to 2022. Among repressors, it grew just 26 per cent.

In fact, when it comes to income growth per person, increases in economic freedom seem to matter even more than a state’s overall, long-term level of freedom. Meanwhile, when it comes to population growth, placing highly over longer periods of time matters more.

The liberators are not unique. There’s now a large body of international evidence documenting the freedom-prosperity connection. At the state level, high and growing levels of economic freedom go hand-in-hand with higher levels of income, entrepreneurship, in-migration and income mobility. In economically free states, incomes tend to grow faster at the top and bottom of the income ladder.

These states suffer less poverty, homelessness and food insecurity and may even have marginally happier, more philanthropic and more tolerant populations.

In short, liberation works. Repression doesn’t.

Alberta

Alberta Next Panel calls for less Ottawa—and it could pay off

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill

Last Friday, less than a week before Christmas, the Smith government quietly released the final report from its Alberta Next Panel, which assessed Alberta’s role in Canada. Among other things, the panel recommends that the federal government transfer some of its tax revenue to provincial governments so they can assume more control over the delivery of provincial services. Based on Canada’s experience in the 1990s, this plan could deliver real benefits for Albertans and all Canadians.

Federations such as Canada typically work best when governments stick to their constitutional lanes. Indeed, one of the benefits of being a federalist country is that different levels of government assume responsibility for programs they’re best suited to deliver. For example, it’s logical that the federal government handle national defence, while provincial governments are typically best positioned to understand and address the unique health-care and education needs of their citizens.

But there’s currently a mismatch between the share of taxes the provinces collect and the cost of delivering provincial responsibilities (e.g. health care, education, childcare, and social services). As such, Ottawa uses transfers—including the Canada Health Transfer (CHT)—to financially support the provinces in their areas of responsibility. But these funds come with conditions.

Consider health care. To receive CHT payments from Ottawa, provinces must abide by the Canada Health Act, which effectively prevents the provinces from experimenting with new ways of delivering and financing health care—including policies that are successful in other universal health-care countries. Given Canada’s health-care system is one of the developed world’s most expensive universal systems, yet Canadians face some of the longest wait times for physicians and worst access to medical technology (e.g. MRIs) and hospital beds, these restrictions limit badly needed innovation and hurt patients.

To give the provinces more flexibility, the Alberta Next Panel suggests the federal government shift tax points (and transfer GST) to the provinces to better align provincial revenues with provincial responsibilities while eliminating “strings” attached to such federal transfers. In other words, Ottawa would transfer a portion of its tax revenues from the federal income tax and federal sales tax to the provincial government so they have funds to experiment with what works best for their citizens, without conditions on how that money can be used.

According to the Alberta Next Panel poll, at least in Alberta, a majority of citizens support this type of provincial autonomy in delivering provincial programs—and again, it’s paid off before.

In the 1990s, amid a fiscal crisis (greater in scale, but not dissimilar to the one Ottawa faces today), the federal government reduced welfare and social assistance transfers to the provinces while simultaneously removing most of the “strings” attached to these dollars. These reforms allowed the provinces to introduce work incentives, for example, which would have previously triggered a reduction in federal transfers. The change to federal transfers sparked a wave of reforms as the provinces experimented with new ways to improve their welfare programs, and ultimately led to significant innovation that reduced welfare dependency from a high of 3.1 million in 1994 to a low of 1.6 million in 2008, while also reducing government spending on social assistance.

The Smith government’s Alberta Next Panel wants the federal government to transfer some of its tax revenues to the provinces and reduce restrictions on provincial program delivery. As Canada’s experience in the 1990s shows, this could spur real innovation that ultimately improves services for Albertans and all Canadians.

-

Haultain Research1 day ago

Haultain Research1 day agoSweden Fixed What Canada Won’t Even Name

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoWhat Do Loyalty Rewards Programs Cost Us?

-

Business22 hours ago

Business22 hours agoLand use will be British Columbia’s biggest issue in 2026

-

International11 hours ago

International11 hours agoChina Stages Massive Live-Fire Encirclement Drill Around Taiwan as Washington and Japan Fortify

-

Digital ID9 hours ago

Digital ID9 hours agoThe Global Push for Government Mandated Digital IDs And Why You Should Worry

-

Business7 hours ago

Business7 hours agoFeds pull the plug on small business grants to Minnesota after massive fraud reports

-

Energy23 hours ago

Energy23 hours agoWhy Japan wants Western Canadian LNG

-

Business20 hours ago

Business20 hours agoMainstream media missing in action as YouTuber blows lid off massive taxpayer fraud