Aristotle Foundation

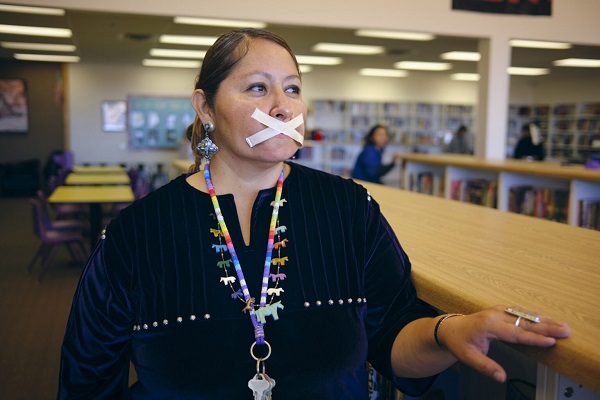

Criminalizing residential school ‘denialism’ would silence indigenous voices, too

By Mark Milke

The effort by MP Leah Gazan to criminalize residential school views she labels “denialist” is a mistake. Gazan’s Bill C-413, if passed, would criminalize any statement that might be interpreted as “condoning, denying, downplaying or justifying the Indian residential school system in Canada through statements communicated other than in private conversation.”

Let’s start with examples of whose speech Gazan’s bill would criminalize, if repeated in the future: indigenous Canadians who have publicly “condoned,” or at least partly justified, residential schools.

In 1998, Rita Galloway, a teacher who grew up on the Pelican Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan and then-president of the First Nations Accountability Coalition, was interviewed about residential schools. She noted that she had “many friends and relatives who attended residential schools,” and argued, “Of course there were good and bad elements, but overall, their experiences were positive.”

In 2008, the late Richard Wagamese, an Ojibwe author and journalist, wrote in the Calgary Herald about the many abuses that took place at residential schools. He then straightforwardly argued that positive stories needed to be told, too, including his mother’s.

After praising her neat, clean home and cultured lawn on a reserve outside Kenora, Ont., Wagamese noted how his 75-year-old mother “credits the residential school experience with teaching her domestic skills.” Critically, “My mother has never spoken to me of abuse or any catastrophic experience at the school.”

Wagamese argued the then-forthcoming Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) “needs to hear those kinds of stories, too,” and that telling “the good along with the bad” will “create a more balanced future for all of us.”

That’s not because such schools were perfect — or even optimal. As has been extensively documented, physical and sexual abuses occurred in some schools, and that is something that no one should downplay.

But it’s too easy to forget the limited choices that existed for 19th- and early 20th-century Canadians. As we do today, most people back then believed in the value of universal education. Many Canadians, indigenous and non-indigenous, lived in poverty, had rudimentary transportation links, limited job opportunities and thus limited possibilities for day schools in remote areas, such as reserves.

Imagine the outcry today if earlier generations of parishioners, parents (including Indigenous parents) and politicians mostly ignored remote reserves and failed to provide indigenous communities with educational opportunities. The same voices today who accept no nuance on residential schools would likely excoriate that choice to deny education to Indigenous children.

The choices in the 19th and 20th centuries were not between perfection and its opposite; they represent a trade-off between suboptimal choices. Understanding this requires nuance, which is in short supply these days.

As an example, consider the perspective of Manitoba school trustee Paul Coffey, a Metis man who made a presentation to the Mountain View School Division board meeting in Dauphin, Man., about racism in April and was pilloried for it. His remarks included comments about residential schools. Coffey tried to argue that residential schools had good and bad aspects, but he was roundly criticized for his views.

In a July interview, Coffey again offered nuance about the schools, noting what much of the media missed in their initial firestorm coverage: “I said they were nice. I then also said they weren’t. I said treaties were nice and then they weren’t. I said even TRC is a good idea, until it isn’t.”

Criminalizing these stories and opinions would mean that these three indigenous voices, and many others, could face fines or jail time. This is precisely why speech, unless urging violence, should never be criminalized.

Another reason not to criminalize speech is because it makes it even more difficult to correct bad ideas and lingering injustices. An open society requires open discourse. It’s the only way errors can only be corrected. That disappears if one becomes subject to fines and imprisonment for thinking out loud, including when one is ultimately proved to be in error.

Gazan’s bill is the latest attempt by Canadian politicians to suppress views and conclusions with which they disagree. That suppression is illiberal and unhelpful. Mandating a single point of view damages the accumulation of knowledge that’s necessary for progress, prevents a useful dissection of why abuses occurred in residential schools and will prevent the open discrediting of wrongheaded positions.

No one person will be right every time. Open, public debate is critical to exposing errors and advancing human progress.

Mark Milke is the president of the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy.

Aristotle Foundation

The extreme ideology behind B.C.’s radical reconciliation agenda

BC government advisors believe ‘settlers’ must atone for Canada’s ‘original sin’

British Columbians are understandably perplexed as to why their provincial government is going headlong down an economically devastating, undemocratic and divisive “reconciliation” path that is so obviously counter to the public interest.

But the reason is simple, and it’s in plain view for anyone who cares to look. Premier David Eby has surrounded himself with advisors who fervently believe in a radical ideology that sees the drastic reshaping of our society as a moral imperative.

One advisor has even suggested that Canada’s formation is analogous to an “original sin,” and his recipe for redemption demands — in his own words — turbulence, rupture, sacrifice, pain, and the utter transformation of human affairs.

Understanding this alarming worldview is necessary for anyone concerned with where things are headed on the reconciliation front.

In early November, Eby came as close as he’s ever been to revealing the “original sin” mentality behind his agenda, stating in a video that changes resulting from B.C.’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA) are “about correcting that original colonial mistake.”

This isn’t just a passing remark. It’s a tip of his hand exposing a disconcerting philosophy long held and frequently expressed by his hand-selected reconciliation advisors.

Doug White and Dr. Roshan Danesh both played key roles in expanding B.C.’s Indigenous policies.

White serves Eby directly as special counsel to the premier on reconciliation, providing guidance on Indigenous policy and the implementation of DRIPA, which is the B.C. government’s enabling legislation that gets its framework from the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Danesh served the government as a facilitator on reconciliation and wrote the report upon which the province’s interim approach to implementing DRIPA’s section 3 was based (this is a crucial section that requires the province to take “all measures necessary” to ensure consistency between the laws of B.C. and UNDRIP).

In addition, both White and Danesh have been officially acknowledged for playing an “absolutely fundamental role” in the Haida agreement. That agreement set a concerning policy precedent by recognizing Aboriginal title over private property in B.C. for the first time, a precursor to the B.C. Supreme Court’s seriously problematic Cowichan decision, which has created considerable uncertainty for property owners across the province.

Given the critical role played by White and Danesh in some of the province’s most consequential reconciliation initiatives, it’s important to understand their views on what reconciliation truly requires.

In a 2023 joint article titled “Rising to the Challenge of Reconciliation,” Danesh and White write of their desire to achieve “turbulent transition,” and of how “this moment in history is one of rupture.”

“We cannot build the new,” they write, “on infirm foundations.” Achieving true reconciliation “will require human affairs to be utterly reorganized. We must all be persistent and audacious in our efforts to advance and achieve this outcome.”

The changes involved in the “work of true reconciliation” are described in the article as analogous to “the struggle of a human being coming of age. At such a time, widely accepted practices and conventions, cherished attitudes and habits, are one by one being rendered obsolete.”

When asked about the article’s revolutionary language during legislative debates in 2024, then-minister of Indigenous relations Murray Rankin responded that the language in the article did “not strike (him) as extreme at all.” He went on to say reconciliation “is not for sissies.”

Danesh had previously expressed such views in a 2021 video on reconciliation saying, “this appeal to harmony in conditions of injustice is really just the veiling over of systems of oppression all over again. The hard work, the real work of building unity is not hanging out and getting along with each other and being understanding. It involves sacrifice. It involves structural, systemic, individual, collective societal change.” In the same video, he calls for “painful” change that ought to “reshap(e) the patterns of relations.”

In a paper for the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs in 2019, White explicitly summons the notion of “original sin.” He explains that “transformative” federal and provincial programs “hold the potential to place the future on a different course — one which significantly diverges from the original sin of Canada.”

Danesh similarly speaks of “original sin,” and its consequences for Crown title and private property rights. In a 2020 paper for B.C.’s First Nations Energy and Mining Council, he writes, “the history of colonialism has created what might be called the ‘domino effect’ among property rights in Canada. The original sin of ignoring Indigenous title, and as such denying Aboriginal title, knocks down much of what has been presumed to be aspects of Crown title in Canadian history, which then knocks down much of the foundation for certainty of fee simple property title,” — the standard form of private land ownership in Canada.

Radical perspectives on land ownership are not confined to Eby’s advisors. They are held by key elected members of his government as well.

In 2023, then-minister for mining Josie Osborne commented, “our approach to natural-resource development must be done in collaboration and partnership with the rightful owners of the land.”

Current Indigenous relations minister Spencer Chandra Herbert, in reference to 1.2 million acres of public land on the Sunshine Coast, has said, “if it’s (shíshálh Nation’s) land, they get to make decisions on it.”

And Eby’s previous Indigenous relations minister, Christine Boyle, is a staunch believer in the “LandBack” movement, an initiative that has been critical of Canada and the provinces’ “stubborn insistence… that they own the land” and that holds that change must involve “Canada ceding real jurisdiction to Indigenous peoples.”

Another B.C. NDP MLA, Rohini Arora, suggested in the legislature that non-Indigenous British Columbians are “settlers,” “colonizers,” and “uninvited guests,” to the applause of her colleagues.

Eby and his reconciliation advisors are fiercely committed to an atonement project of massive proportions for an “original sin” they believe mars the very conception of this country. Expiation will require turbulent and painful change that renders obsolete our “cherished habits.” And they will undertake “persistent and audacious” efforts aimed at a drastic reorganization of human affairs to achieve it.

Only when we understand the ideology underlying the B.C. government’s radical reconciliation agenda can we comprehend where things are going. And right now, we’re being zealously led towards an ungovernable province in pursuit of absolution.

Caroline Elliott is a senior fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. Photo: Legislative Assembly of British Columbia Reconciliation Action Plan 2024-2028.

Aristotle Foundation

We’re all “settlers”

By Mark Milke and Tom Flanagan

The settler-indigenous distinction is false. We all originated in Africa.

If Canadians care to understand why our country is increasingly fractured, one key driver is the notion that non-Indigenous Canadians — “settlers” as they are called — should be grateful to live anywhere in the Americas.

The “settler” label is mostly directed at those of British and European ancestry. But it can apply to anyone whose families arrived from anywhere — Africa, Asia, the Levant, the Pacific — who were not part of the prior waves of migration to the Americas.

According to the most recent scientific knowledge, human settlement in the Americas began about 15,000 to 20,000 years ago. These pioneers of settlement must have arrived from Asia by boat and hopscotched along the Pacific coast because the interior land was glaciated. They migrated as far south as modern-day Chile, but it is unknown how far inland they penetrated and whether they survived to merge with later migratory settlers.

Another wave of migration started around 13,000 years ago when an ice-free corridor opened through Alberta between the two great glaciers covering North America. This made it possible for people from the now submerged land of Beringia to move south through Alaska, Yukon and Alberta across North America.

Later, but at an unknown date, came the movement of the Dene-speaking peoples now living mostly in Alaska and Canada’s North (though the Tsuut’ina got to southern Alberta and the Navajo to the southwestern United States). Their languages still show traces of their relatively recent Siberian origins.

The Inuit migrated from Siberia across the Arctic to Greenland around AD 1000. Another group inhabited the Arctic starting around 2500 BC, but their relationship to the Inuit is uncertain.

In short, the Americas were settled in waves from Asia. Everyone alive today is descended from settlers. The latest “Indigenous” settlers arrived barely ahead of the first European settlers, the Vikings, who settled in Greenland and Newfoundland, and of Christopher Columbus, who started Spanish settlement in the Caribbean.

Singling out Europeans as “settlers” drives land acknowledgments, as well as demands for compensation and reconciliation. It plays on guilt about the actions of actors long since dead, while the concurrent demands for land, decision-making power and financial settlements occur on an open-ended basis. Internationally, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) also assumes the Indigenous vs. settler-colonial divide is valid.

Why does this matter? Because peaceful, relatively prosperous nation-states are not guaranteed to last. In fact, they’re the exception, not the rule. To make actual progress in unifying Canada as opposed to watching it break down and fragment into hundreds of inconsequential principalities (a separate Quebec, a separate Alberta, and multiple First Nations with state-like powers, of which there would be up to 200 in British Columbia alone), it is overdue to dissect these assumptions, and the related belief that Canadians have done little to make up for some of the wrongs done in history.

Language clarifications

Let’s begin with language.

The notion that some groups in the Americas have been here since “time immemorial” and thus are indigenous in the truest sense of that term is evolutionarily and historically false. The evolutionary origin of every human being lies in Africa, where Homo sapiens evolved as a distinct species about 315,000 years ago. Also, as Encyclopædia Britannica notes, “we were preceded for millions of years by other hominins, such as Ardipithecus, Australopithecus, and other species of Homo.”

The fact that all of us jointly link back to origins in Africa should be enough to stop using the “time immemorial” phrase, as well as any artificial distinction between those considered “Indigenous,” whose ancestors arrived in separate waves of migration separated by thousands of years, and those considered “settlers,” whose ancestors arrived during the last 500 years.

That some people’s ancestors beat others by 19,500 years or less to what we now call Canada does not create a permanent obligation on the part of later arrivals, or their progeny, to those whose families arrived first, just as Indigenous people today are not responsible for the actions of their own ancestors against other tribes over thousands of years. In the grand scheme of evolutionary time, all our ancestors’ lives were but a relative blip.

The ‘stolen land’ assertion

A stronger argument might be that later settlers owe the families of earlier settlers for stealing their land, which is a popular claim. However, that assertion ignores the multitude of treaties signed across Canada as well as the very approach by the colonial British and Sir John A. Macdonald that treaties were preferable to brazen conquest, as happened with other empires throughout history, including those now labelled Indigenous.

Further, that not every inch of Canada is covered by treaty still does not negate how the Canadian nation-state provided funds even to those First Nations not covered by treaty — in British Columbia, for example. Or how the 1982 constitutional amendments recognized Aboriginal and treaty rights, which are being constantly expanded by Canadian courts.

Moreover, the first Europeans and later British did not come to the Americas and “steal” a $2.5 trillion economy (Canada’s GDP in 2025). Rather, the earlier inhabitants were followed by French fur traders, Scottish explorers, Western farmers, Toronto financiers, Atlantic and Pacific fishermen, British and Asian workers, entrepreneurs in the 19th and 20th centuries and many other arrivals. All of them built Canada up. They did so with their own sweat, time and investment. That’s why farms feed Canadian families, mines provide steel for automobiles, natural gas and hydroelectricity heat homes, and skyscrapers can be built on First Nations reserves — because all “settlers” together made modern-day Canada possible.

Reconciliation considerations: Money flows and tax exemptions

Whenever reconciliation conversations begin, they inevitably assume “stolen” land as per above and ignore the significant past and present cash transfers as well as generous tax exemptions — many of which are not constitutionally required but exist as a result of the Indian Act, and thus could have been eliminated at any point in our collective history but were not.

Let’s follow the money. In 2013, one of us (Milke) authored the first comprehensive Fraser Institute report on the money spent in just the postwar world until 2012, at the federal and provincial levels, on Indigenous Canadians, including those once called “treaty Indians” but also others.

The results? In 2013 dollars (i.e., adjusted for inflation), in what was then known as the Department of Indian Affairs, spending on Canada’s Aboriginal peoples rose to almost $7.9 billion by 2011-12 from $79 million annually in 1946-47. That was an increase from $922 per Indigenous person per year to $9,056 — a rise of 882 per cent. By comparison, total federal program spending per person on all Canadians in the same years rose by 387 per cent. Of course, Indigenous Canadians are also eligible for and receive other government spending because they are Canadians.

Another one of us (Flanagan), updated that report and published several of his own for the Fraser Institute, which echoed the findings of the 2013 report on Aboriginal spending: ever-higher budgetary spending, plus eye-popping recent settlements of lawsuits. The largest of these was a $40 billion settlement in 2022 for children taken from reserves into foster care.

Spending on Indigenous programs and services in the 2024-25 budget was $32 billion, nearly triple what it was 10 years ago, even as outcomes have not measurably improved. Multiple multi-billion-dollar financial settlements also continue to be awarded every year, on top of the program and services funding itemized in the budget.

In addition to the child welfare settlement noted above, ponder a $10 billion settlement in 2023 related to the Robinson Huron Treaty (including individual payments of at least $110,000 per person), and an $8.5 billion agreement in 2025 to reform First Nations child and family services in Ontario, among others.

Much of the above spending on Indigenous peoples goes beyond traditional treaty and constitutional requirements. There is also much more to come. In the federal departments of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, beyond “routine” spending on Indigenous Canadians, several transfer programs explicitly provide funds to Indigenous Canadians and/or to support further claims upon the public purse.

That’s the spending side. Now the tax exemptions. In 2024, Flanagan published a report for the Aristotle Foundation on tax exemptions given to First Nations under Section 87 of the Indian Act. That’s the longstanding tax exemption for real and personal property owned by “Indians,” including employment income, on reserves. One incomplete estimate from 2015 quantified the value of those exemptions at roughly $1.3 billion a year.

At some point — we suggest now — all this should count towards the “paid” column in the reconciliation ledger.

The mistaken morality play

Financial matters aside, what drives one-sided reconciliation talk in Canada is not only the mistaken claim that those now labelled “Indigenous” have existed in the Americas from “time immemorial,” a creationist myth, but that pre-contact, First Nations were unlike all other human beings in history — peaceful with each other, and at one with the environment.

This image is ludicrously far from historical fact. Amerindians were environmentalists only because their small numbers limited the environmental damage they caused. And warfare was endemic among them. At the time of the American Revolution, the Iroquois were waging war to create an empire in Ontario and the American Midwest. The Ojibwe and Cree, originally woodland peoples, blasted their way onto the prairies after they got guns from the Hudson’s Bay Company. As late as 1870, the Cree and Blackfoot, both weakened by smallpox, fought a lethal battle near the site of modern Lethbridge, which is still remembered in tribal lore.

As the Romans said, Vae victis (“woe to the conquered.”) If the losers in intra-Indigenous wars did not die in battle, they were often tortured to death or enslaved. Slavery was practiced on a particularly large scale on the Pacific coast, where slaves could be put to work cutting wood. Indigenous slavery persisted in British Columbia even after that province joined Confederation and still has echoes today. And in other parts of the Americas, pre-contact, human sacrifice was practiced. It was of course colonialists — the British in Canada as only one example — who ended such practices.

How Indigenous identity politics imitate … Europe

Chopping up Canada into ever-more tribal enclaves is historically reminiscent of the continent often vilified in modern-day discourse: Europe. Both before the Roman Empire and after its collapse into the medieval age and until at least 1945 in various forms, the innate tribalism of Europe has long been costly in blood and treasure.

Mid-20th century historian Will Durant described the after-effects of the collapse of that empire and how Europe retreated into today what we could call “balkanization”: “half-isolated economic units in the countryside,” “state revenues declined as commerce contracted and industry fell,” and “impoverished governments could no longer provide protection for life, property, and trade.”

Of course, most people in human history have endured what the philosopher Thomas Hobbes described as nasty, brutish and short lives precisely because human beings have, for much of our history, found reasons to divide from each other. They did so most often for less-than-ideal reasons and with even less ideal results. But unlike those under most empires (at one end of possible political organization) or tribes (at the other), what mostly began as a British colonial experiment and is now modern-day Canada increasingly gave rights and prosperity to a diverse set of peoples — all of us “settlers.”

Of those who wish to turn Canada into a thousand mini-fiefdoms, we ask the same question Pierre Trudeau asked during a speech to a Montreal crowd during the 1980 referendum on separation. After describing Canada’s virtues and also the interdependent world we live in, Trudeau challenged the separatist-isolationists this way: “These people in Quebec and in Canada want to split it up? They want to take it away from their children? They want to break it down? No! — that’s our answer!” to which the crowd roared their approval.

What about one Canada for all?

The mostly peaceful northern country of Canada was not an accident but a conscious creation, mostly of the British, after their win on the Plains of Abraham in 1759 (with Indigenous allies, it should be noted). That led to the eventual victory of the British in 1763 and Canada’s eventual creation as a nation-state in 1867. Its success over centuries, pre- and post-Confederation, but especially in the postwar world, is also due to 19th-century British presumptions which fully flowered in the last century. That included expanded freedoms for all, including in 1960 when Indigenous Canadians were rightfully restored the right to vote.

Canada’s accomplishments include individual rights, including equality before the law and in policy (with the noted exception of reverse discrimination and DEI); legal protection of property rights (albeit not constitutionalized), a mostly open, free economy; the rule of law and independent courts; and democratic rule, among other achievements rare in human history.

There are thus two questions every Canadian today should ask.

First, was the arrival of later settlers, be they French or British in the 16th and 17th centuries and beyond, and later arrivals from Africa and Asia, mostly a positive development? We would argue that the answer is “yes” for all the above-noted reasons: Increasing freedoms for all over time, more prosperity, and peace on the northern half of the North American continent.

Second, the most fundamentally important question we can ask of each other in 2025 is not “When did your ancestors arrive here?” but “What kind of Canada do we want in the future?” Little good and much harm will come from destroying our inheritance, including private property, or ramping up identity politics which comes at the expense of equality of the individual, or continuing down the path of balkanization.

The better future for Canada is one where all are treated as equal in law and policy as much as practically possible. It is one where property rights are secure and the economy thrives, and where the “fusion” of peoples from all over the world continues what the first settlers began 20,000 years ago: A near-miraculous project where Canada is renewed to be a free, flourishing country where all are welcome.

Mark Milke is the president of the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. Tom Flanagan is a senior fellow at the Aristotle Foundation. Photo credit: iStock.

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoThe Canadian Energy Centre’s biggest stories of 2025

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoResurfaced Video Shows How Somali Scammers Used Day Care Centers To Scam State

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoIn Contentious Canada Reality Is Still Six Degrees Of Hockey

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoMinneapolis day care filmed empty suddenly fills with kids

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoDisclosures reveal Minnesota politician’s husband’s companies surged thousands-fold amid Somali fraud crisis

-

Business12 hours ago

Business12 hours agoDark clouds loom over Canada’s economy in 2026

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoDOOR TO DOOR: Feds descend on Minneapolis day cares tied to massive fraud

-

Addictions9 hours ago

Addictions9 hours agoCoffee, Nicotine, and the Politics of Acceptable Addiction