Business

Carbon tax costs Canadian economy $12 billion this year

From the Canadian Taxpayers Federation

Author: Franco Terrazzano

The Canadian Taxpayers Federation estimates the carbon tax will cost the Canadian economy $12 billion in 2024, based on data published by Environment and Climate Change Canada.

“The government’s own data shows the carbon tax costs our economy billions of dollars every year,” said Franco Terrazzano, CTF Federal Director. “Prime Minister Justin Trudeau should immediately make life more affordable and help the economy by scrapping his carbon tax.”

The government of Canada released data modelling the economic cost of the carbon tax between 2018 and 2030. Based on this data, the CTF estimates the carbon tax will cost the Canadian economy $12 billion in 2024, or an estimated $295 per person.

In 2030, the carbon tax will cost the Canadian economy $30 billion, or an estimated $678 per person based on Statistics Canada population projections.

The economic cost is the difference between what GDP would be without the carbon tax minus the projected GDP with the carbon tax.

The table at the end of this news release breaks down the economic cost to each province and territory and the economic cost per person this year.

“The carbon tax costs Canadians big time for gas, home heating bills and everything else,” Terrazzano said. “And the carbon tax is a huge drag on the Canadian economy that we just can’t afford.”

Economic cost of carbon tax (2023 $)

| Region | Economic cost 2024 | Per person economic cost |

| Canada |

$11.9 billion |

$295 |

| British Columbia |

$1.7 billion |

$311 |

| Alberta |

$1.8 billion |

$372 |

| Saskatchewan |

$476 million |

$390 |

| Manitoba |

$216 million |

$150 |

| Ontario |

$4.1 billion |

$258 |

| Quebec |

$3.2 billion |

$361 |

| New Brunswick |

$137 million |

$169 |

| Nova Scotia |

$103 million |

$99 |

| Prince Edward Island |

$22 million |

$122 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador |

$143 million |

$274 |

| Northwest Territories |

-$15 million |

-$324 |

| Yukon |

$6 million |

$136 |

| Nunavut |

$14 million |

$352 |

Note: A negative figure represents an economic benefit.

Business

Mark Carney’s Fiscal Fantasy Will Bankrupt Canada

By Gwyn Morgan

Mark Carney was supposed to be the adult in the room. After nearly a decade of runaway spending under Justin Trudeau, the former central banker was presented to Canadians as a steady hand – someone who could responsibly manage the economy and restore fiscal discipline.

Instead, Carney has taken Trudeau’s recklessness and dialled it up. His government’s recently released spending plan shows an increase of 8.5 percent this fiscal year to $437.8 billion. Add in “non-budgetary spending” such as EI payouts, plus at least $49 billion just to service the burgeoning national debt and total spending in Carney’s first year in office will hit $554.5 billion.

Even if tax revenues were to remain level with last year – and they almost certainly won’t given the tariff wars ravaging Canadian industry – we are hurtling toward a deficit that could easily exceed 3 percent of GDP, and thus dwarf our meagre annual economic growth. It will only get worse. The Parliamentary Budget Officer estimates debt interest alone will consume $70 billion annually by 2029. Fitch Ratings recently warned of Canada’s “rapid and steep fiscal deterioration”, noting that if the Liberal program is implemented total federal, provincial and local debt would rise to 90 percent of GDP.

This was already a fiscal powder keg. But then Carney casually tossed in a lit match. At June’s NATO summit, he pledged to raise defence spending to 2 percent of GDP this fiscal year – to roughly $62 billion. Days later, he stunned even his own caucus by promising to match NATO’s new 5 percent target. If he and his Liberal colleagues follow through, Canada’s defence spending will balloon to the current annual equivalent of $155 billion per year. There is no plan to pay for this. It will all go on the national credit card.

This is not “responsible government.” It is economic madness.

And it’s happening amid broader economic decline. Business investment per worker – a key driver of productivity and living standards – has been shrinking since 2015. The C.D. Howe Institute warns that Canadian workers are increasingly “underequipped compared to their peers abroad,” making us less competitive and less prosperous.

The problem isn’t a lack of money; it’s a lack of discipline and vision. We’ve created a business climate that punishes investment: high taxes, sluggish regulatory processes, and politically motivated uncertainty. Carney has done nothing to reverse this. If anything, he’s making the situation worse.

Recall the 2008 global financial meltdown. Carney loves to highlight his role as Bank of Canada Governor during that time but the true credit for steering the country through the crisis belongs to then-prime minister Stephen Harper and his finance minister, Jim Flaherty. Facing the pressures of a minority Parliament, they made the tough decisions that safeguarded Canada’s fiscal foundation. Their disciplined governance is something Carney would do well to emulate.

Instead, he’s tearing down that legacy. His recent $4.3 billion aid pledge to Ukraine, made without parliamentary approval, exemplifies his careless approach. And his self-proclaimed image as the experienced technocrat who could go eyeball-to-eyeball against Trump is starting to crack. Instead of respecting Carney, Trump is almost toying with him, announcing in June, for example that the U.S. would pull out of the much-ballyhooed bilateral trade talks launched at the G7 Summit less than two weeks earlier.

Ordinary Canadians will foot the bill for Carney’s fiscal mess. The dollar has weakened. Young Canadians – already priced out of the housing market – will inherit a mountain of debt. This is not stewardship. It’s generational theft.

Some still believe Carney will pivot – that he will eventually govern sensibly. But nothing in his actions supports that hope. A leader serious about economic renewal would cancel wasteful Trudeau-era programs, streamline approvals for energy and resource projects, and offer incentives for capital investment. Instead, we’re getting more borrowing and ideological showmanship.

It’s no longer credible to say Carney is better than Trudeau. He’s worse. Trudeau at least pretended deficits were temporary. Carney has made them permanent – and more dangerous.

This is a betrayal of the fiscal stability Canadians were promised. If we care about our credit rating, our standard of living, or the future we are leaving our children, we must change course.

That begins by removing a government unwilling – or unable – to do the job.

Canada once set an economic example for others. Those days are gone. The warning signs – soaring debt, declining productivity, and diminished global standing – are everywhere. Carney’s defenders may still hope he can grow into the job. Canada cannot afford to wait and find out.

The original, full-length version of this article was recently published in C2C Journal.

Gwyn Morgan is a retired business leader who was a director of five global corporations.

Business

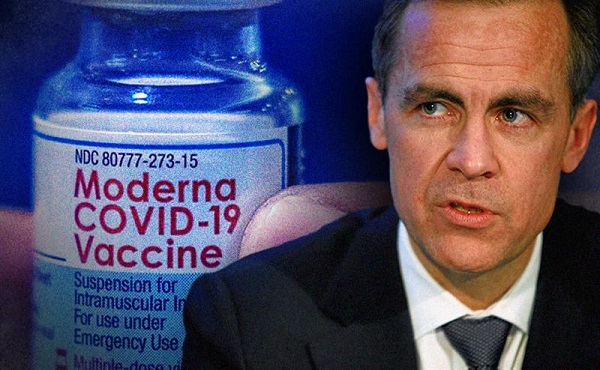

Carney Liberals quietly award Pfizer, Moderna nearly $400 million for new COVID shot contracts

From LifeSiteNews

Carney’s Liberal government signed nearly $400 million in contracts with Pfizer and Moderna for COVID shots, despite halted booster programs and ongoing delays in compensating Canadians for jab injuries.

Prime Minister Mark Carney has awarded Pfizer and Moderna nearly $400 million in new COVID shot contracts.

On June 30th, the Liberal government quietly signed nearly $400 million contracts with vaccine companies Pfizer and Moderna for COVID jabs, despite thousands of Canadians waiting to receive compensation for COVID shot injuries.

The contracts, published on the Government of Canada website, run from June 30, 2025, until March 31, 2026. Under the contracts, taxpayers must pay $199,907,418.00 to both companies for their COVID shots.

Notably, there have been no press releases regarding the contracts on the Government of Canada website nor from Carney’s official office.

Additionally, the contracts were signed after most Canadians provinces halted their COVID booster shot programs. At the same time, many Canadians are still waiting to receive compensation from COVID shot injuries.

Canada’s Vaccine Injury Support Program (VISP) was launched in December 2020 after the Canadian government gave vaccine makers a shield from liability regarding COVID-19 jab-related injuries.

There has been a total of 3,317 claims received, of which only 234 have received payments. In December, the Canadian Department of Health warned that COVID shot injury payouts will exceed the $75 million budget.

The December memo is the last public update that Canadians have received regarding the cost of the program. However, private investigations have revealed that much of the funding is going in the pockets of administrators, not injured Canadians.

A July report by Global News discovered that Oxaro Inc., the consulting company overseeing the VISP, has received $50.6 million. Of that fund, $33.7 million has been spent on administrative costs, compared to only $16.9 million going to vaccine injured Canadians.

Furthermore, the claims do not represent the total number of Canadians injured by the allegedly “safe and effective” COVID shots, as inside memos have revealed that the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) officials neglected to report all adverse effects from COVID jabs and even went as far as telling staff not to report all events.

The PHAC’s downplaying of jab injuries is of little surprise to Canadians, as a 2023 secret memo revealed that the federal government purposefully hid adverse effect so as not to alarm Canadians.

The secret memo from former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Privy Council Office noted that COVID jab injuries and even deaths “have the potential to shake public confidence.”

“Adverse effects following immunization, news reports and the government’s response to them have the potential to shake public confidence in the COVID-19 vaccination rollout,” read a part of the memo titled “Testing Behaviourally Informed Messaging in Response to Severe Adverse Events Following Immunization.”

Instead of alerting the public, the secret memo suggested developing “winning communication strategies” to ensure the public did not lose confidence in the experimental injections.

Since the start of the COVID crisis, official data shows that the virus has been listed as the cause of death for less than 20 children in Canada under age 15. This is out of six million children in the age group.

The COVID jabs approved in Canada have also been associated with severe side effects, such as blood clots, rashes, miscarriages, and even heart attacks in young, healthy men.

Additionally, a recent study done by researchers with Canada-based Correlation Research in the Public Interest showed that 17 countries have found a “definite causal link” between peaks in all-cause mortality and the fast rollouts of the COVID shots, as well as boosters.

Interestingly, while the Department of Health has spent $16 million on injury payouts, the Liberal government spent $54 million COVID propaganda promoting the shot to young Canadians.

The Public Health Agency of Canada especially targeted young Canadians ages 18-24 because they “may play down the seriousness of the situation.”

-

Uncategorized14 hours ago

Uncategorized14 hours agoCNN’s Shock Climate Polling Data Reinforces Trump’s Energy Agenda

-

illegal immigration2 days ago

illegal immigration2 days agoICE raids California pot farm, uncovers illegal aliens and child labor

-

Opinion7 hours ago

Opinion7 hours agoPreston Manning: Three Wise Men from the East, Again

-

Addictions6 hours ago

Addictions6 hours agoWhy B.C.’s new witnessed dosing guidelines are built to fail

-

Business4 hours ago

Business4 hours agoCarney Liberals quietly award Pfizer, Moderna nearly $400 million for new COVID shot contracts

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoTrump to impose 30% tariff on EU, Mexico

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoLNG Export Marks Beginning Of Canadian Energy Independence

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney government should apply lessons from 1990s in spending review