armed forces

Canadians are finally waking up to the funding crisis that’s sent the Canadian Armed Forces into a “death spiral”

From the Macdonald Laurier Institute

By By J.L. Granatstein

Must we wait for Trump to attack free trade between Canada and the US before our politicians get the message that defence matters to Washington?

Nations have interests – national interests – that lay out their ultimate priorities. The first one for every country is to protect its population and territory. It is sometimes hard to tell, but this also applies to Canada. Ottawa’s primary job is to make sure that Canada and Canadians are safe. And Canada also has a second priority: to work with our allies to protect their and our freedom. As we share this continent with the United States, this means that we must pay close attention to our neighbouring superpower.

Regrettably for the last six decades or so we have not done this very well. During the 1950s, the Liberal government of Louis St. Laurent in some years spent more than 7 percent of GDP on defence, making Canada the most militarily credible of the middle powers. His successors whittled down defence spending and cut the numbers of troops, ships, and aircraft. By the end of the Cold War, in the early 1990s, our forces had shrunk, and their equipment was increasingly obsolescent.

Another Liberal prime minister, Jean Chrétien, balanced the budget in 1998 by slashing the military even more, and by getting rid of most of the procurement experts at the Department of National Defence, he gave us many of the problems the Canadian Armed Forces face today. Canadians and their governments wanted social security measures, not troops with tanks, and they got their wish.

There was another factor of significant importance, though it is one usually forgotten. Lester Pearson’s Nobel Peace Prize for helping to freeze the Suez Crisis of 1956 convinced Canadians that they were natural-born peacekeepers. Give a soldier a blue beret and an unloaded rifle and he could be the representative of Canada as the moral superpower we wanted to be. The Yanks fought wars, but Canada kept the peace, or so we believed, and Canada for decades had servicemen and women in every peacekeeping operation.

There were problems with this. First, peacekeeping didn’t really work that well. It might contain a conflict, but it rarely resolved one – unless the parties to the dispute wanted peace. In Cyprus, for example, where Canadians served for three decades, neither the Greek- or Turkish-Cypriots wanted peace; nor did their backers in Athens and Ankara. The Cold War’s end also unleashed ethnic nationalisms, and Yugoslavia, for one, fractured into conflicts between Serbs, Croats, Bosnians, Christians, and Muslims, leading to all-out war. Peacekeepers tried to hold the lid on, but it took NATO to bash heads to bring a truce if not peace.

And there was a particular Canadian problem with peacekeeping. If all that was needed was a stock of blue berets and small arms, our governments asked, why spend vast sums on the military? Peacekeeping was cheap, and this belief sped up the budget cuts.

Even worse, the public believed the hype and began to resist the idea that the Canadian Armed Forces should do anything else. For instance, the Chrétien government took Canada into Afghanistan in 2001 to participate in what became a war to dislodge the Taliban, but huge numbers of Canadians believed that this was really only peacekeeping with a few hiccups.

Stephen Harper’s Conservative government nonetheless gave the CAF the equipment it needed to fight in Afghanistan, and the troops did well. But the casualties increased as the fighting went on, and Harper pulled Canada out of the conflict well before the Taliban seized power again in 2021.

Harper’s successor, Liberal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, clearly has no interest in the military except as a somewhat rogue element that needs to be tamed, made comfortable for its members, and to act as a social laboratory with quotas for visible minorities and women.

Is this an exaggeration? This was Trudeau’s mandate letter to his defence minister in December 2021: “Your immediate priority is to take concrete steps to build an inclusive and diverse Defence Team, characterized by a healthy workplace free from harassment, discrimination, sexual misconduct, and violence.” DND quickly permitted facial piercings, coloured nail polish, beards, long hair, and, literally, male soldiers in skirts, so long as the hem fell below the knees. This was followed by almost an entire issue of the CAF’s official publication, Canadian Military Journal, devoted to culture change in the most extreme terms. You can’t make this stuff up.

Thus, our present crisis: a military short some 15,000 men and women, with none of the quotas near being met. A defence minister who tells a conference the CAF is in a “death spiral” because of its inability to recruit soldiers. (Somehow no one in Ottawa connects the culture change foolishness to a lack of recruits.) Fighter pilots, specialized sailors, and senior NCOs, their morale broken, taking early retirement. Obsolete equipment because of procurement failures and decade-long delays. Escalating costs for ships, aircraft, and trucks because every order requires that domestic firms get their cut, no matter if that hikes prices even higher. The failure to meet a NATO accord, agreed to by Canada, that defence spending be at least 2 percent of GDP, and no prospect that Canada will ever meet this threshold.

But something has changed.

Three opinion polls at the beginning of March all reported similar results: the Canadian public – worried about Russia and Putin’s war against Ukraine, and anxious about China, North Korea, and Iran (all countries with undemocratic regimes and, Iran temporarily excepted, nuclear weapons) – has noticed at last that Canada is unarmed and undefended. Canadians are watching with concern as Ottawa is scorned by its allies in NATO, Washington, and the Five Eyes intelligence sharing alliance.

At the same time, official Department of National Defence documents laid out the alarming deficiencies in the CAF’s readiness: too few soldiers ready to respond to crises and not enough equipment that is in working order for those that are ready.

The bottom line? Canadians finally seem willing to accept more spending on defence.

The media have been hammering at the government’s shortcomings. So have retired generals. General Rick Hillier, the former chief of the defence staff, was especially blunt: “[The CAF’s] equipment has been relegated to sort-of-broken equipment parked by the fence. Our fighting ships are on limitations to the speed that they can sail or the waves that they can sail in. Our aircraft, until they’re replaced, they’re old and sort of not in that kind of fight anymore. And so, I feel sorry for the men and women who are serving there right now.”

The Trudeau government has repeatedly demonstrated that it simply does not care. It offers more money for the CBC and for seniors’ dental care, pharmaceuticals, and other vote-winning objectives, but nothing for defence (where DND’s allocations astonishingly have been cut by some $1 billion this year and at least the next two years). There is no hope for change from the Liberals, their pacifistic NDP partners, or from the Bloc Québécois.

The Conservative Party, well ahead in the polls, looks to be in position to form the next government. What will they do for the military? So far, we don’t know – Pierre Poilievre has been remarkably coy. The Conservative leader has said he wants to cut wasteful spending and eliminate foreign aid to dictatorial regimes and corrupted UN agencies like UNRWA. He says he will slash the bureaucracy and reform the procurement shambles in Ottawa, and he will “work towards” spending on the CAF to bring us to the equivalent of 2 percent of GDP. His staff say that Poilievre is not skeptical about the idea of collective security and NATO; rather, he is committed to balancing the books.

What this all means is clear enough. No one should expect that a Conservative government will move quickly to spend much more on defence than the Grits. A promise to “work towards” 2 percent is not enough, and certainly not if former US President Donald Trump ends up in the White House again. Must we wait for Trump to attack free trade between Canada and the US before our politicians get the message that defence matters to Washington? Unfortunately, it seems so, and Canadians will not be able to say that they weren’t warned. After all, it should be obvious that it is in our national interest to protect ourselves.

J.L. Granatstein taught Canadian history, was Director and CEO of the Canadian War Museum, and writes on military and political history. His most recent book is Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace. (3rd edition).

armed forces

Canada’s Military Can’t Be Fixed With Cash Alone

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Michel Maisonneuve

Canada’s military is broken, and unless Ottawa backs its spending with real reform, we’re just playing politics with national security

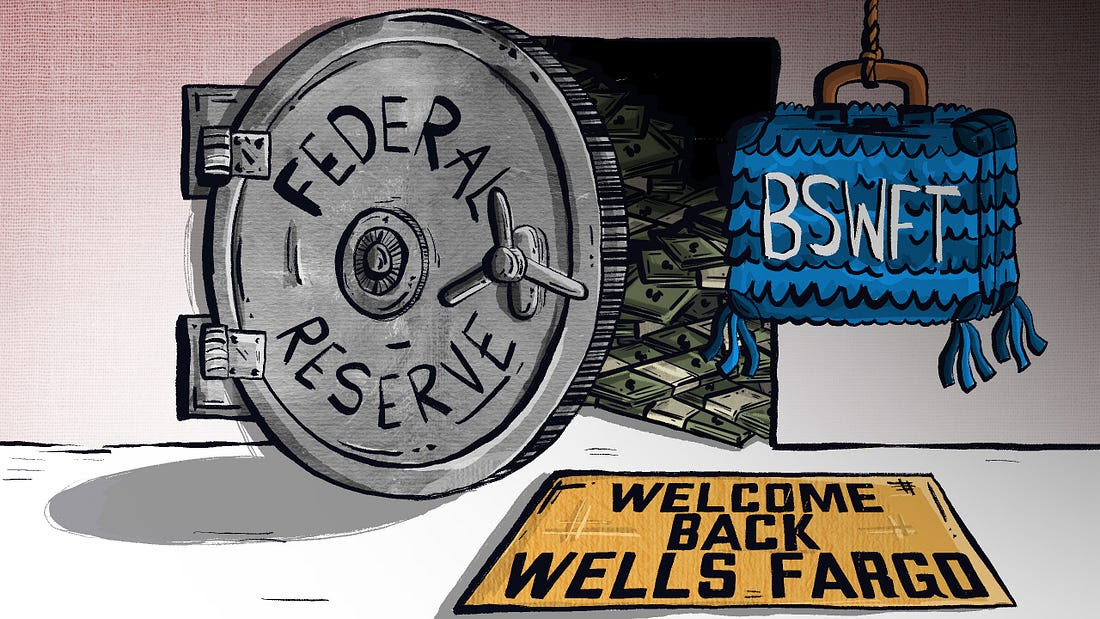

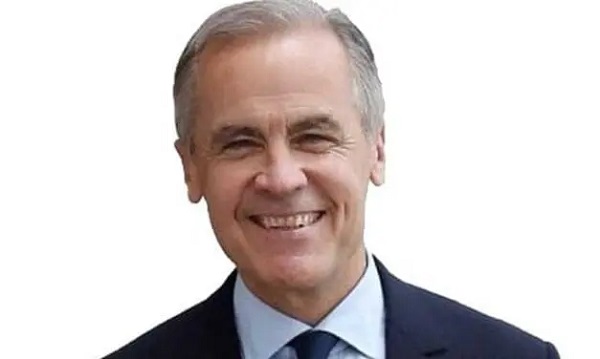

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s surprise pledge to meet NATO’s defence spending target is long overdue, but without real reform, leadership and a shift away from bureaucracy and social experimentation, it risks falling short of what the moment demands.

Canada committed in 2014 to spend two per cent of its gross national product on defence—a NATO target meant to ensure collective security and more equitable burden-sharing. We never made it past 1.37 per cent, drawing criticism from allies and, in my view, breaching our obligation. Now, the prime minister says we’ll hit the target by the end of fiscal year 2025-26. That’s welcome news, but it comes with serious challenges.

Reaching the two per cent was always possible. It just required political courage. The announced $9 billion in new defence spending shows intent, and Carney’s remarks about protecting Canadians are encouraging. But the reality is our military readiness is at a breaking point. With global instability rising—including conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East—Canada’s ability to defend its territory or contribute meaningfully to NATO is under scrutiny. Less than half of our army vehicles, ships and aircraft are currently operational.

I’m told the Treasury Board has already approved the new funds, making this more than just political spin. Much of the money appears to be going where it’s most needed: personnel. Pay and benefit increases for serving members should help with retention, and bonuses for re-enlistment are reportedly being considered. Recruiting and civilian staffing will also get a boost, though I question adding more to an already bloated public service. Reserves and cadet programs weren’t mentioned but they also need attention.

Equipment upgrades are just as urgent. A new procurement agency is planned, overseen by a secretary of state—hopefully with members in uniform involved. In the meantime, accelerating existing projects is a good way to ensure the money flows quickly. Restocking ammunition is a priority. Buying Canadian and diversifying suppliers makes sense. The Business Council of Canada has signalled its support for a national defence industrial strategy. That’s encouraging, but none of it will matter without follow-through.

Infrastructure is also in dire shape. Bases, housing, training facilities and armouries are in disrepair. Rebuilding these will not only help operations but also improve recruitment and retention. So will improved training, including more sea days, flying hours and field operations.

All of this looks promising on paper, but if the Department of National Defence can’t spend funds effectively, it won’t matter. Around $1 billion a year typically lapses due to missing project staff and excessive bureaucracy. As one colleague warned, “implementation [of the program] … must occur as a whole-of-government activity, with trust-based partnerships across industry and academe, or else it will fail.”

The defence budget also remains discretionary. Unlike health transfers or old age security, which are legally entrenched, defence funding can be cut at will. That creates instability for military suppliers and risks turning long-term procurement into a political football. The new funds must be protected from short-term fiscal pressure and partisan meddling.

One more concern: culture. If Canada is serious about rebuilding its military, we must move past performative diversity policies and return to a warrior ethos. That means recruiting the best men and women based on merit, instilling discipline and honour, and giving them the tools to fight and, if necessary, make the ultimate sacrifice. The military must reflect Canadian values, but it is not a place for social experimentation or reduced standards.

Finally, the announcement came without a federal budget or fiscal roadmap. Canada’s deficits continue to grow. Taxpayers deserve transparency. What trade-offs will be required to fund this? If this plan is just a last-minute attempt to appease U.S. President Donald Trump ahead of the G7 or our NATO allies at next month’s summit, it won’t stand the test of time.

Canada has the resources, talent and standing to be a serious middle power. But only action—not announcements—will prove whether we truly intend to be one.

The NATO summit is over, and Canada was barely at the table. With global threats rising, Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Michel Maisonneuve joins David Leis to ask: How do we rebuild our national defence—and why does it matter to every Canadian? Because this isn’t just about security. It’s about our economy, our identity, and whether Canada remains sovereign—or becomes the 51st state.

Michel Maisonneuve is a retired lieutenant-general who served 45 years in uniform. He is a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy and author of In Defence of Canada: Reflections of a Patriot (2024).

armed forces

Mark Carney Thinks He’s Cinderella At The Ball

And we all pay when the dancing ends

How to explain Mark Carney’s obsession with Europe and his lack of attention to Canada’s economy and an actual budget?

Carney’s pirouette through NATO meetings, always in his custom-tailored navy blue power suits, carries the desperate whiff of an insecure, small-town outsider who has made it big but will always yearn for old-money credibility. Canada is too young a country, too dynamic and at times a bit too vulgar to claim equal status with Europe’s formerly magnificent and ancient cultures — now failed under the yoke of globalism.

Hysterical foreign policy, unchecked immigration, burgeoning censorship and massive income disparity have conquered much of the continent that many of us used to admire and were even somewhat intimidated by. But we’ve moved on. And yet Carney seems stuck, seeking approval and direction from modern Europe — a place where, for most countries, the glory days are long gone.

Carney’s irresponsible financial commitment to NATO is a reckless and unnecessary expenditure, given that many Canadians are hurting. But it allowed Carney to pick up another photo of himself glad-handing global elites to whom he just sold out his struggling citizens.

From the Globe and Mail

“Prime Minister Mark Carney has committed Canada to the biggest increase in military spending since the Second World War, part of a NATO pledge designed to address the threat of Russian expansionism and to keep Donald Trump from quitting the Western alliance.

Mr. Carney and the leaders of the 31 other member countries issued a joint statement Wednesday at The Hague saying they would raise defence-related spending to the equivalent of 5 per cent of their gross domestic product by 2035.

NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte said the commitment means “European allies and Canada will do more of the heavy lifting” and take “greater responsibility for our shared security.”

For Canada, this will require spending an additional $50-billion to $90-billion a year – more than doubling the existing defence budget to between $110-billion and $150-billion by 2035, depending on how much the economy grows. This year Ottawa’s defence-related spending is due to top $62-billion.”

You’ll note that spending money we don’t have in order to keep President Trump happy is hardly an elbows up moment, especially given that the pledge followed Carney’s embarrassing interactions with Trump at the G7. I’m all for diplomacy but sick to my teeth of Carney’s two-faced approach to everything. There is no objective truth to anything our prime minister touches. Watch the first few minutes of the video below.

The portents are bad. This from the Globe:

We are poorer than we think. Canadians running their retirement numbers are shining light in the dark corners of household finances in this country. The sums leave many “anxious, fearful and sad about their finances,” according to a Healthcare of Ontario Pension Plan survey recently reported in these pages.

Fifty-two per cent of us worry a lot about our personal finances. Fifty per cent feel frustrated, 47 per cent feel emotionally drained and 43 per cent feel depressed. There is not one survey indicator to suggest Canadians have made financial progress in 2025 compared with 2024.

The video below is a basic “F”- you to Canadians from a Prime Minister who smirks and roles his eyes when questioned about his inept money management.

He did spill the beans to CNN with this unsettling revelation about the staggering numbers we are talking about:

Signing on to NATO’s new defence spending target could cost the federal treasury up to $150 billion a year, Prime Minister Mark Carney said Tuesday in advance of the Western military alliance’s annual summit.

The prime minister made the comments in an interview with CNN International.

“It is a lot of money,” Carney said.

This guy was a banker?

We are witnessing the political equivalent of a vain woman who blows her entire paycheque to look good for an aspirational event even though she can’t afford food or rent. Yes, she sparkled for a moment, but in reality her domaine is crumbling. All she has left are the photographs of her glittery night. Our Prime Minister is collecting his own album of power-proximity photos he can use to wallpaper over his failures as our economy collapses.

The glass slipper doesn’t fit.

Trish Wood is Critical is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoBlackouts Coming If America Continues With Biden-Era Green Frenzy, Trump Admin Warns

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days ago‘I Know How These People Operate’: Fmr CIA Officer Calls BS On FBI’s New Epstein Intel

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoChicago suburb purchases childhood home of Pope Leo XIV

-

Crime23 hours ago

Crime23 hours agoTrump supporters cry foul after DOJ memo buries the Epstein sex trafficking scandal

-

Daily Caller23 hours ago

Daily Caller23 hours agoTrump Issues Order To End Green Energy Gravy Train, Cites National Security

-

Daily Caller16 hours ago

Daily Caller16 hours agoUSAID Quietly Sent Thousands Of Viruses To Chinese Military-Linked Biolab

-

Addictions16 hours ago

Addictions16 hours ago‘Over and over until they die’: Drug crisis pushes first responders to the brink

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoPrime minister can make good on campaign promise by reforming Canada Health Act