Business

Canada’s risky and misguided bet on EV battery manufacturing

From the Macdonald Laurier Institute

By Tom McCaffrey and Denaige McDonnell for Inside Policy

By investing $52.5 billion in a handful of foreign-controlled companies, the government has failed to create a sustainable, long-term economic advantage. Instead of fostering innovation and building a robust, homegrown supply chain, Canada has committed itself to an outdated model of industrial policy that relies on foreign entities and low-value manufacturing jobs.

Two years ago, Canada’s minister of natural resources urged Canadians “to fully seize” the economic opportunity presented by the country’s abundant critical minerals.

“We must ensure that value is added to the entire supply chain, including exploration, extraction, intermediate processing, advanced manufacturing, and recycling,” Jonathan Wilkinson stated. “We must create the necessary conditions for Canadian companies to grow, scale-up, and expand globally in markets that depend on critical minerals.”

Two years later, the Canadian government has gone all-in with a $52.5 billion dollar bet on EV battery manufacturing in Ontario and Quebec. The decision goes against the recommendations of industry specialists and the government’s own departments responsible for strategic development who advised officials to go slow, steady, and think full supply chain development when targeting incentives.

Why didn’t the politicians listen?

Ottawa’s risky bet on EV battery manufacturing

By 2033, the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) estimates three recent Canadian Government EV battery manufacturing subsidies will cost the country a total $37.7 billion dollars. The Northvolt, Volkswagen, Stellantis-LGES manufacturing facilities are estimated to take 15 years to pay back Canadian taxpayers.

The repayment estimate is 6 years longer than the government originally estimated because the PBO has now used the manufacturers’ production rate estimations, a more conservative number, than the originally used full production rates. In total, the national investment across the full value chain of EV battery manufacturing equates to $52.5 billion into just 13 companies.

The Canadian government is betting big on EVs, but not by investing in innovation, intellectual property, or Canadian technology. It is betting the farm on foreign entities delivering 8,500 manufacturing jobs. Capital investment for the purpose of growth in labour productivity isn’t a new strategy and it can be effective, but at $4 million per job the likelihood of return on investment is low.

Could the Bet Pay Off?

The global EV battery market is expected to surge over the next 10 years from US$132.6 billion in 2023 to US$508.8 by 2033. So far, growth has been slower than expected, and some major players, like Tesla, will be challenged to meet their sales volumes from last year according to analysts – but basing an opinion on a single year of car sales is not wise.

The truth is car manufacturing in Canada is important to our GDP ($14.6 billion) and to jobs (125,000). It is also true that Canada has lost 50 per cent of its market share in manufacturing of cars ($8 billion in 2000 to $4 billion in 2022), but it has maintained it market share in motor vehicle parts ($9 billion).

Canada appears to be betting that it can maintain it’s position in the car automotive industry rather than cementing its place in the battery metals and manufacturing value chain. But is this wager wise?

Sustainable policy development

Governments can encourage economic and industrial development in several ways. Policy-makers can set efficient regulations and approval mechanisms; create frameworks that build a bridge between government and the private sector; support the development of skilled labour and innovation ecosystems; enable direct collaboration and procurement mechanisms between industry, academia, innovation ecosystems, and government; and share a clear vision and pathway for industrial growth.

Governments can also use subsidies and tax credits to create market share, but there is growing concern that using these methods to create or protect markets will cause more harm than opportunity in developing countries. These kinds of investments risk triggering international protectionism and geopolitical trade-offs as nations turn inward rather than collaborating for development.

What’s needed is a sustainable policy approach – one that influences and benefits the largest subset of market outcomes, including start-up development, foreign direct investment, technology development, technology adoption, investment attraction, the creation of circular economy value chains, and more.

Ottawa’s misguided approach to economic investment

In the EV world, a fully integrated supply chain that includes mining, chemical processing, battery production, and recycling is critical. The battery value chain road map published by Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) Canada, and the Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy published by Natural Resources Canada (NRC) both call for government to develop the full supply chain.

In 2021, a standing committee advised how best to develop the full supply chain. That same year Clean Energy Canada wrote a report on how Canada could build the domestic battery industry across the country, and in 2022 another full suite of associations including the Battery Metals Association, Energy Futures Lab, Transition Accelerator, and Accelerate ZEV developed a roadmap to develop Canada’s battery value chain.

The Canadian industrial policies being used to create the EV supply chain are a mix of production subsidies, investment tax credits, foregone corporate income tax revenue, construction capital expenses, and other monetary supports. Though large, the $52.5 billion investment ignores key aspects of the upstream supply chain (mining, refining, etc.) that would allow us to reap full value from EV battery production. Worse, it comes at a time when automakers are pulling back from EV investments due to lower than expected demands, making the investment increasingly risky given changing market conditions.

By flying in the face of the very industries it supports and specialists it employs, it raises the question: why is Canadian government failing to follow its own strategy? Why choose to support an undeveloped strategy that banks on foreign investment and manufacturing jobs when experts across Canada’s supply chain, and two government departments, had a fulsome and balanced approach to supply chain development? Why shun a balanced approach to government investment focused on building out the entire supply chain?

Where Canada continues to go astray

Canada’s investment strategies have long been plagued by short-term thinking, favouring politically motivated quick wins over sustainable, long-term value creation. The government’s $52.5 billion bet on EV battery manufacturing is a prime example—subsidizing foreign companies while neglecting the development of critical upstream supply chains and domestic innovation. This approach leaves Canada reliant on international markets for critical materials, with little to show in terms of intellectual property or R&D growth.

By ignoring expert advice and focusing on politically strategic regions, Canada misses opportunities to build fully integrated industries across the country, ultimately failing to support homegrown solutions that could foster long-term economic resilience. Instead, Canada continues to prioritize high-risk, low-return investments, with little consideration for the foundational elements needed for a competitive, innovative economy.

Research on industrial policy shows countries are better served when governments focus on delivering well-designed policies aimed at improving general business environments than attempting to artificially create new markets. This is why industrial policies went out of vogue more than two decades ago.

It raises the question – are there examples of successful government interventions that seeded new sectors?

How the Asia-Pacific region cornered the semiconductor market

In the 1980s both the South Korea and Taiwanese governments made strategic early investments in companies that were well positioned to accelerate growth of the semiconductor sector. Today, the Asia-Pacific region is dominating the global market share of what has become a US$620 billion industry. Both South Korea and Taiwan were investing in the semiconductor industry in the 1960s. From a policy perspective, the two countries took similar approaches and focused their state-directed capital allocations to companies like Samsung LG and the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). Through strong government support, both countries created technology institutes, centres for research and development, infrastructure and tax incentives, tax holidays, and interest-free loans.

Those investments helped to seed highly successful sectors in each country. Both countries continue to invest tax dollars back into the sector to help maintain the competitive advantages they helped to foster. South Korea’s semiconductor industry received a $US19 billion show of support from its government earlier this year to create a comprehensive support program spanning financial, research and development, and infrastructure support. The investment is part of a decades long commitment to the semiconductor industry which now accounts for nearly 20 per cent of total exports and plays a leading role in the South Korean economy. In Taiwan, the semiconductor sector is a powerhouse that accounts for 15 per cent of the national GDP and ranks number one globally for wafer foundry and packaging and testing, and number two for integrated circuit (IC) design.

These successes were largely enabled by government-controlled economies and early, and ongoing support to industry. This support did not waiver for decades. It is unlikely that Canada will be able to maintain this level of stability and government focus.

Other factors like access to cheap labour, willingness to specialize, commitment to product quality, and streamlined manufacturing played an important role.

Policy Challenges: Economic and Political Complexities

The challenge of creating successful industrial policy is that it is complex, long-term, has uncertain benefits, and requires government departments to have deep industry expertise. Experts worry that the current federal government simply isn’t up to the task.

In 2023, more than 2,500 new industrial policies were introduced globally, and more than 70 per cent were subsidies, tariffs, or import/export restrictions. These policies create trade distortion more often than they lead to market creation. Trade distortion can unfairly tilt the playing field in favour of domestic industries, often at the expense of foreign competitors.

With Canada’s recent industrial policy on EV battery manufacturing, we are choosing to distort our own economy.

Industrial policies strain global trade and economic relations. Such policies can have wide-ranging effects on both the implementing country and the global economy. They also appear protectionist even to allied nations.

How can Canada get it right?

Many of Canada’s mature sectors have enjoyed government support or protection at some point in our nation’s history. Past Canadian governments have protected the industries of their time, be it agriculture, steel manufacturing, pulp and paper, aerospace, and even defence.

There are recent examples of small sums of government dollars creating big wins for Canada’s homegrown innovation and sustainability economy.

At the provincial level, one organization that stands out is Emissions Reduction Alberta (ERA), an arms-length provincial organization that has weather several changes in government in its 15 years. ERA uses Technology Innovation and Emissions Reduction dollars to invest in late-stage sustainable technology. To date, the organization has invested almost $1 billion dollars into 277 technologies at a ratio of 8 industry dollars to 1 ERA dollar.

Federally, Prairies Economic Development Canada (PrairiesCan) is an example of a highly innovative approach to economic development. It has invested millions of dollars in repayable interest-free loans and regional innovation ecosystem supports. Ecosystem supports include accelerators and incubators that have exponentially increased the success of start ups and mature firms alike.

PrairiesCan and ERA operate on annual budgets of $300 million and $50–200 million, respectively. These dollars employ various types of expertise and invest across large swaths of the mature and new economy. They look across hundreds of organizations, understand the regional context, varying business dynamics and make strategic investments.

If government persists in committing tax dollars to the growth of the economy, then it should draw inspiration from these kinds of organizations.

Do Governments Make Effective Market Makers?

Canadians are rightly skeptical about Ottawa’s $52.5 billion bet on EV battery manufacturing.

Ottawa is rolling the dice that it will make Canada a leader in battery supply chains. It’s one of the largest industrial policy bets we have seen in our lifetimes. However, industrial policy analysts are warning about the risk of misallocation of funds.

Expert critics say Canada’s economy is too reliant on government-driven innovation policies. These researchers believe that competition creates markets, and that the government should commit to focusing on reducing policy and regulatory barriers. Many still believe in the capitalist ethos – that fostering a cultural and economic environment that naturally supports risk-taking and competition is the best route to success. The same people would note that the natural process of business turnover is essential for innovation and growth.

Conclusion

Canada’s current strategy of picking winners through massive, targeted subsidies is not just risky – it’s short-sighted. By investing $52.5 billion in a handful of foreign-controlled companies, the government has failed to create a sustainable, long-term economic advantage. Instead of fostering innovation and building a robust, homegrown supply chain, Canada has committed itself to an outdated model of industrial policy that relies on foreign entities and low-value manufacturing jobs. This approach ignores the foundational elements that drive true competitiveness – innovation, R&D, and full value chain development.

What Canada needs is a fundamental shift in its investment strategy. Instead of betting the farm on politically motivated, high-risk subsidies, the government should focus on strengthening ecosystems that support innovation, entrepreneurship, and domestic industry. Investments should be directed at building a fully integrated supply chain that includes mining, refining, and manufacturing, while supporting Canadian companies that will keep intellectual property and jobs at home.

If Canada continues down the current path, it risks becoming a player in someone else’s game, perpetually reliant on foreign companies and global markets. The country should seize this moment to redefine its complete industrial strategy, making bold investments in innovation and infrastructure that can secure economic resilience for generations to come. Without this shift, Canada’s $52.5 billion bet may very well be remembered as one of the biggest missed opportunities in modern economic history.

Tom McCaffery, M.B.A., is the CEO and managing director of Two River Advisory and former executive director of policy and engagement for Emissions Reduction Alberta.

Denaige McDonnell, Ph.D., is an accomplished business management strategist and CEO of People Risk Management, specializing in organizational systems, culture, and psychological safety.

Business

Largest fraud in US history? Independent Journalist visits numerous daycare centres with no children, revealing massive scam

A young journalist has uncovered perhaps the largest fraud scheme in US history.

He certainly isn’t a polished reporter with many years of experience, but 23 year old independent journalist Nick Shirley seems to be getting the job done. Shirley has released an incredible video which appears to outline fraud after fraud after fraud in what appears to be a massive taxpayer funded scheme involving up to $9 Billion Dollars.

In one day of traveling around Minneapolis-St. Paul, Shirley appears to uncover over $100 million in fraudulent operations.

🚨 Here is the full 42 minutes of my crew and I exposing Minnesota fraud, this might be my most important work yet. We uncovered over $110,000,000 in ONE day. Like it and share it around like wildfire! Its time to hold these corrupt politicians and fraudsters accountable

We ALL… pic.twitter.com/E3Penx2o7a

— Nick shirley (@nickshirleyy) December 26, 2025

Business

“Magnitude cannot be overstated”: Minnesota aid scam may reach $9 billion

Federal prosecutors say Minnesota’s exploding social-services fraud scandal may now rival nearly the entire economy of Somalia, with as much as $9 billion allegedly stolen from taxpayer-funded programs in what authorities describe as industrial-scale abuse that unfolded largely under the watch of Democrat Gov. Tim Walz. The staggering new estimate is almost nine times higher than the roughly $1 billion figure previously suspected and amounts to about half of the $18 billion in federal funds routed through Minnesota-run social-services programs since 2018, according to prosecutors. “The magnitude cannot be overstated,” First Assistant U.S. Attorney Joe Thompson said Thursday, stressing that investigators are still uncovering massive schemes. “This is not a handful of bad actors. It’s staggering, industrial-scale fraud. Every day we look under a rock and find another $50 million fraud operation.”

Authorities say the alleged theft went far beyond routine overbilling. Dozens of defendants — the vast majority tied to Minnesota’s Somali community — are accused of creating sham businesses and nonprofits that claimed to provide housing assistance, food aid, or health-care services that never existed, then billing state programs backed by federal dollars. Thompson said the opportunity became so lucrative it attracted what he called “fraud tourism,” with out-of-state operators traveling to Minnesota to cash in. Charges announced Thursday against six more people bring the total number of defendants to 92.

BREAKING: First Assistant U.S. Attorney Joe Thompson revealed that 14 state Medicaid programs have cost Minnesota $18 billion since 2018, including more than $3.5 billion in 2024 alone.

Thompson stated, "Now, I'm sure everyone is wondering how much of this $18 billion was… pic.twitter.com/hCNDBuCTYH

— FOX 9 (@FOX9) December 18, 2025

Among the newly charged are Anthony Waddell Jefferson, 37, and Lester Brown, 53, who prosecutors say traveled from Philadelphia to Minnesota after spotting what they believed was easy money in the state’s housing assistance system. The pair allegedly embedded themselves in shelters and affordable-housing networks to pose as legitimate providers, then recruited relatives and associates to fabricate client notes. Prosecutors say they submitted about $3.5 million in false claims to the state’s Housing Stability Services Program for roughly 230 supposed clients.

Other cases show how deeply the alleged fraud penetrated Minnesota’s health-care programs. Abdinajib Hassan Yussuf, 27, is accused of setting up a bogus autism therapy nonprofit that paid parents to enroll children regardless of diagnosis, then billed the state for services never delivered, netting roughly $6 million. Another defendant, Asha Farhan Hassan, 28, allegedly participated in a separate autism scheme that generated $14 million in fraudulent reimbursements, while also pocketing nearly $500,000 through the notorious Feeding Our Future food-aid scandal. “Roughly two dozen Feeding Our Future defendants were getting money from autism clinics,” Thompson said. “That’s how we learned about the autism fraud.”

The broader scandal began to unravel in 2022 when Feeding Our Future collapsed under federal investigation, but prosecutors say only in recent months has the true scope of the alleged theft come into focus. Investigators allege large sums were wired overseas or spent on luxury vehicles and other high-end purchases. The revelations have fueled political fallout in Minnesota and prompted renewed federal scrutiny of immigration-linked fraud as well as criticism of state oversight failures. Walz, who is seeking re-election in 2026 after serving as Kamala Harris’ running mate in 2024, defended his administration Thursday, saying, “We will not tolerate fraud, and we will continue to work with federal partners to ensure fraud is stopped and fraudsters are caught.” Prosecutors, however, made clear the investigation is far from finished — and warned the final tally could climb even higher.

-

Censorship Industrial Complex12 hours ago

Censorship Industrial Complex12 hours agoUS Under Secretary of State Slams UK and EU Over Online Speech Regulation, Announces Release of Files on Past Censorship Efforts

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta project would be “the biggest carbon capture and storage project in the world”

-

Energy2 days ago

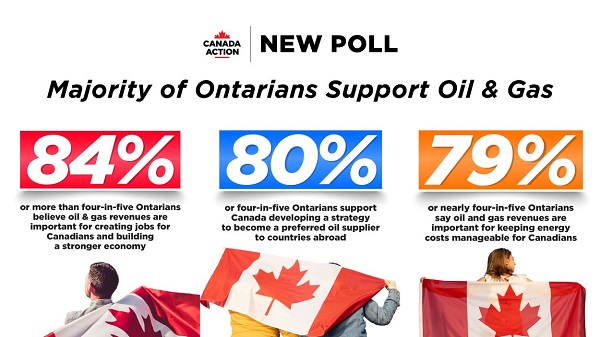

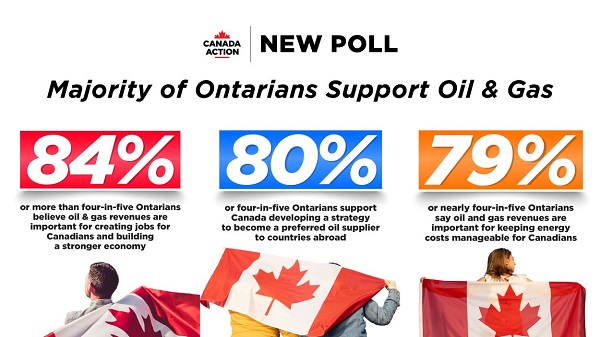

Energy2 days agoNew Poll Shows Ontarians See Oil & Gas as Key to Jobs, Economy, and Trade

-

Business15 hours ago

Business15 hours ago“Magnitude cannot be overstated”: Minnesota aid scam may reach $9 billion

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoSocialism vs. Capitalism

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoCanada’s debate on energy levelled up in 2025

-

Fraser Institute2 days ago

Fraser Institute2 days agoCarney government sowing seeds for corruption in Ottawa

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoIs Ukraine Peace Deal Doomed Before Zelenskyy And Trump Even Meet At Mar-A-Lago?