Break The Needle

Canada-US border mayors react to new border security initiative

US President Donald Trump has linked his threat to impose 25-per-cent tariffs on Canadian goods to Canada’s failure to address drug trafficking and illegal migration at the Canada-US border.

Ontario has responded with a border security initiative, Operation Deterrence, which is drawing tepid support from Ontario mayors of border communities.

“Absence of leadership from Ottawa has created this [scenario] where the provinces are all going in to be Captain, or Miss Captain, Canada,” said Mike Bradley, the mayor of Sarnia, Ont., a city of 75,000 that sits on the Ontario-Michigan border.

“[But] anything that helps on the policing side to deal with the black plague of fentanyl is welcome,” Bradley said.

Operation Deterrence

On Dec. 6, Ontario redeployed 200 Ontario Provincial Police officers to unpoliced border areas near the 14 official Ontario-US border crossings, which are staffed by the Canada Border Services Agency.

Officers are using aircraft, drones, boats, off-road vehicles and foot patrols to “deter, detect and disrupt” the illegal trafficking of drugs, guns and people, a Jan. 7 provincial press release says.

Premier Ford’s office and Ontario Solicitor General Michael Kerzner declined to provide further details about the operation in response to requests for comment.

But a spokesperson for the Ontario RCMP said there is little evidence that fentanyl trafficking is a significant issue at the Canada-US border.

“There is limited to no evidence or data from law enforcement agencies in the U.S. or Canada to support the claim that Canadian-produced fentanyl is an increasing threat to the U.S.,” the spokesperson told Canadian Affairs in an emailed statement.

The spokesperson highlighted that fentanyl trafficking frequently occurs by mail, rather than at physical border crossings.

“Reports state fentanyl produced in Canada is being exported in micro shipments, most often through the mail. Micro traffickers are most often found on the dark web,” the spokesperson said.

As Canadian Affairs reported last week, seizures of fentanyl at the Canada-US border remain relatively low. But Canadian authorities have seized significant volumes of precursor chemicals used in the production of fentanyl, and key sources say Canada is a major player in the global fentanyl trade.

Data also show illegal migration is a concern along the Canada-US border.

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported nearly 200,000 cases of individuals in Canada trying to illegally enter the US in the 2024 fiscal year.

Canada Border Services Agency data indicate just under 5,000 individuals were detained trying to enter Canada from the US in 2023-24.

Borderlands

Jim Diodati, the mayor of Niagara Falls, says he is supportive of Ontario launching Operation Deterrence in response to Trump’s tariff threats.

“I’m glad at least we’re reacting,” he said. “The concerns, of course, are that things are slipping through the cracks … both for drugs, guns and human smuggling as well.”

But Diodati stressed that border concerns go both ways. He hopes Operation Deterrence will also address firearms trafficking from the US into Canada.

“Ninety percent of illegal guns that come into Canada come from the US side, across our borders,” he said.

Diodati blames Ottawa for underfunding the Canada Border Services Agency, the federal agency responsible for border security and immigration enforcement. “CBSA needs more resources,” he said.

“The US sees our border as porous, not as secure as theirs, and now, with the incoming president, they’re looking to punish us over it.”

Bev Hand is the mayor of Point Edward, a 2,500-person village located a short drive north of Sarnia, on the southern tip of Lake Huron. The community connects to Port Huron, Mich., by the Blue Water Bridge, a key Canada-US border crossing.

Hand expressed cautious support for Operation Deterrence’s aims of addressing drug trafficking.

She noted that, since 2019, there have been 16 major drug busts at the Point Edward border, including two significant cocaine seizures by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. In December 2023, US authorities found nearly 500 kg of cocaine in a truck entering the US. In August 2024, US authorities discovered over 120 kg of cocaine hidden in the wall of a truck bound for Canada.

“Fifteen of the seizures were in transport trucks,” she said. “This represents millions of dollars in illegal drugs, and we don’t know what wasn’t captured.”

Hand noted, however, that funds allocated to border security might be better spent on addressing the root causes of drug trafficking, such as addiction.

In December, Ottawa announced it would spend an additional $1.3 billion over six years on enhancing its border security. Ontario has not disclosed how much Operation Deterrence will cost.

Like Diodati, Hand also emphasized the role Operation Deterrence could play in helping to curb firearms trafficking from the US.

She referenced a May 2022 case where a resident discovered a bag with 11 handguns in a tree near Port Lambton, Ont., a city approximately 15 kilometres south of Point Edward.

“The package had fallen from a drone that is assumed to have come from the US side,” she said.

Our content is always free. Subscribe to get BTN’s latest news and analysis, or donate to our journalism fund.

‘Fentanyl Czar’

Bradley, Sarnia’s mayor, said border security initiatives must be balanced against the need to facilitate trade, particularly at critical crossings like the CN Rail tunnel — which runs beneath the St. Clair River and connects Canada to Michigan — and Blue Water Bridge.

“We want security, but you also want trade, and that’s the balance right now that we’re struggling with,” Bradley said.

A 13-year review by professors at Carleton University found that tighter Canada-US border security following the 9/11 attacks increased inspection times and delays at the border. This has “negatively impacted” bilateral trade and cost the Canadian economy billions in foregone economic opportunities and productivity.

Diodati, of Niagara Falls, said he would prefer to see Canada and the US take a bilateral approach to border security that focuses on bolstering security around the continent.

“We want to take a perimeter approach around North America, rather than the borders between us,” he said.

While diplomatic relations between Canada and the US are tense, further collaboration on border security may be on the horizon.

On Feb. 3, Trump paused the imposition of tariffs on Canada after Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised Canada would send nearly 10,000 frontline personnel to protect the border.

“Canada is making new commitments to appoint a Fentanyl Czar, we will list cartels as terrorists, ensure 24/7 eyes on the border, launch a Canada-U.S. Joint Strike Force to combat organized crime, fentanyl and money laundering,” Trudeau wrote in a post on social media platform X.

“I have also signed a new intelligence directive on organized crime and fentanyl and we will be backing it with $200 million.

“Proposed tariffs will be paused for at least 30 days while we work together.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

2025 Federal Election

Study links B.C.’s drug policies to more overdoses, but researchers urge caution

By Alexandra Keeler

A study links B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization to more opioid hospitalizations, but experts note its limitations

A new study says B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization policies may have failed to reduce overdoses. Furthermore, the very policies designed to help drug users may have actually increased hospitalizations.

“Neither the safer opioid supply policy nor the decriminalization of drug possession appeared to mitigate the opioid crisis, and both were associated with an increase in opioid overdose hospitalizations,” the study says.

The study has sparked debate, with some pointing to it as proof that B.C.’s drug policies failed. Others have questioned the study’s methodology and conclusions.

“The question we want to know the answer to [but cannot] is how many opioid hospitalizations would have occurred had the policy not have been implemented,” said Michael Wallace, a biostatistician and associate professor at the University of Waterloo.

“We can never come up with truly definitive conclusions in cases such as this, no matter what data we have, short of being able to magically duplicate B.C.”

Jumping to conclusions

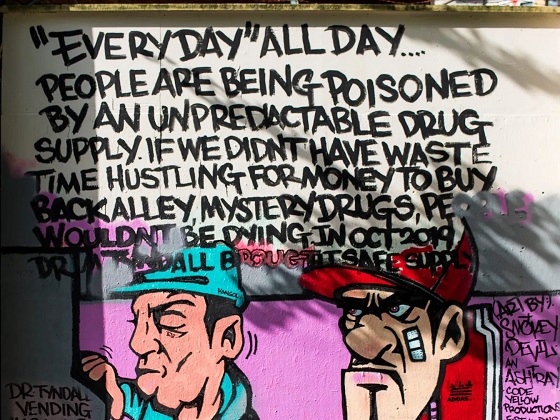

B.C.’s controversial safer supply policies provide drug users with prescription opioids as an alternative to toxic street drugs. Its decriminalization policy permitted drug users to possess otherwise illegal substances for personal use.

The peer-reviewed study was led by health economist Hai Nguyen and conducted by researchers from Memorial University in Newfoundland, the University of Manitoba and Weill Cornell Medicine, a medical school in New York City. It was published in the medical journal JAMA Health Forum on March 21.

The researchers used a statistical method to create a “synthetic” comparison group, since there is no ideal control group. The researchers then compared B.C. to other provinces to assess the impact of certain drug policies.

Examining data from 2016 to 2023, the study links B.C.’s safer supply policies to a 33 per cent rise in opioid hospitalizations.

The study says the province’s decriminalization policies further drove up hospitalizations by 58 per cent.

“Neither the safer supply policy nor the subsequent decriminalization of drug possession appeared to alleviate the opioid crisis,” the study concludes. “Instead, both were associated with an increase in opioid overdose hospitalizations.”

The B.C. government rolled back decriminalization in April 2024 in response to widespread concerns over public drug use. This February, the province also officially acknowledged that diversion of safer supply drugs does occur.

The study did not conclusively determine whether the increase in hospital visits was due to diverted safer supply opioids, the toxic illicit supply, or other factors.

“There was insufficient evidence to conclusively attribute an increase in opioid overdose deaths to these policy changes,” the study says.

Nguyen’s team had published an earlier, 2024 study in JAMA Internal Medicine that also linked safer supply to increased hospitalizations. However, it failed to control for key confounders such as employment rates and naloxone access. Their 2025 study better accounts for these variables using the synthetic comparison group method.

The study’s authors did not respond to Canadian Affairs’ requests for comment.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Correlation vs. causation

Chris Perlman, a health data and addiction expert at the University of Waterloo, says more studies are needed.

He believes the findings are weak, as they show correlation but not causation.

“The study provides a small signal that the rates of hospitalization have changed, but I wouldn’t conclude that it can be solely attributed to the safer supply and decrim[inalization] policy decisions,” said Perlman.

He also noted the rise in hospitalizations doesn’t necessarily mean more overdoses. Rather, more people may be reaching hospitals in time for treatment.

“Given that the [overdose] rate may have gone down, I wonder if we’re simply seeing an effect where more persons survive an overdose and actually receive treatment in hospital where they would have died in the pre-policy time period,” he said.

The Nguyen study acknowledges this possibility.

“The observed increase in opioid hospitalizations, without a corresponding increase in opioid deaths, may reflect greater willingness to seek medical assistance because decriminalization could reduce the stigma associated with drug use,” it says.

“However, it is also possible that reduced stigma and removal of criminal penalties facilitated the diversion of safer opioids, contributing to increased hospitalizations.”

Karen Urbanoski, an associate professor in the Public Health and Social Policy department at the University of Victoria, is more critical.

“The [study’s] findings do not warrant the conclusion that these policies are causally associated with increased hospitalization or overdose,” said Urbanoski, who also holds the Canada Research Chair in Substance Use, Addictions and Health Services.

Her team published a study in November 2023 that measured safer supply’s impact on mortality and acute care visits. It found safer supply opioids did reduce overdose deaths.

Critics, however, raised concerns that her study misrepresented its underlying data and showed no statistically significant reduction in deaths after accounting for confounding factors.

The Nguyen study differs from Urbanoski’s. While Urbanoski’s team focused on individual-level outcomes, the Nguyen study analyzed broader, population-level effects, including diversion.

Wallace, the biostatistician, agrees more individual-level data could strengthen analysis, but does not believe it undermines the study’s conclusions. Wallace thinks the researchers did their best with the available data they had.

“We do not have a ‘copy’ of B.C. where the policies weren’t implemented to compare with,” said Wallace.

B.C.’s overdose rate of 775 per 100,000 is well above the national average of 533.

Elenore Sturko, a Conservative MLA for Surrey-Cloverdale, has been a vocal critic of B.C.’s decriminalization and safer supply policies.

“If the government doesn’t want to believe this study, well then I invite them to do a similar study,” she told reporters on March 27.

“Show us the evidence that they have failed to show us since 2020,” she added, referring to the year B.C. implemented safer supply.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Break The Needle

Why psychedelic therapy is stuck in the waiting room

There is mounting evidence of psychedelics’ effectiveness at treating mental disorders. But researchers face obstacles conducting rigorous studies

In a move that made international headlines, America’s top drug regulator denied approval last year for psychedelic-assisted therapy to treat post-traumatic stress disorder.

In its decision, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration cited concerns about study design and inadequate evidence to assess the benefits and harms of using the drug MDMA.

The decision was a significant setback for psychedelics researchers and veterans’ groups who had been advocating for the therapy to be approved. It is also reflective of a broader challenge faced by researchers keen to validate the therapeutic potential of psychedelics.

“Sometimes I feel like it’s death by 1,000 paper cuts,” said Leah Mayo, a researcher at the University of Calgary.

“If the regulatory burden were a little bit less, that would be helpful,” added Mayo, who holds the Parker Psychedelics Research Chair at the Psychedelic and Cannabinoid Therapeutics Lab. The lab develops new treatments for mental health disorders using psychedelics and cannabinoids.

Sources say the weak research body behind psychedelics is due to a complex interplay of factors. But they would like to see more research conducted to make psychedelics more accessible to people who could benefit from them.

“If you want [psychedelics] to work within existing health-care infrastructure, you have to play by [Canadian research] rules,” said Mayo.

“Therapy has to be reproducible, it has to be evidence-based, it has to be grounded in reality.”

Psychedelics in Canada

Psychedelics are hallucinogenic substances such as psilocybin, MDMA and ketamine that alter people’s perceptions, mood and thought processes. Psychedelic therapy involves the use of psychedelics in guided sessions with therapists to treat mental health conditions.

Psychedelics are generally banned for possession, production and distribution in Canada. However, two per cent of Canadians consumed hallucinogens in 2019, according to the latest Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey. Psychedelics are also used in Canada and abroad in unregulated clinics and settings to treat conditions such as substance use disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and various mental disorders.

“The cat’s out of the bag, and people are using this,” said Zachary Walsh, a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of British Columbia.

Within Canada, there are three ways for psychedelics to be accessed legally.

The federal health minister can approve their use for medical, scientific or public interest purposes. Health Canada runs a Special Access Program that allows doctors to request the use of unapproved drugs for patients with serious conditions that have not responded to other treatments. And Health Canada can approve psychedelics for use in clinical trials.

Researchers interested in conducting clinical trials involving psychedelics face significant hurdles.

“There’s been a concerted effort — and it’s just fading now — to mischaracterize the risks of these substances,” said Walsh, who has conducted several studies on the therapeutic uses of psychedelics. These include studies on MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD, and the effects of microdosing psilocybin on stress, anxiety and depression.

This Substack is reader-supported.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The U.S. government demonized psychedelic substances during its War on Drugs in the 1970s, exaggerating their risks and blocking research into their medical potential. Influenced by this war, Canada adopted similar tough-on-drugs policies and restricted research.

Today, younger researchers are pushing forward.

“New ideas really come into the forefront when the people in charge of the old ideas retire and die,” said Norman Farb, an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Toronto.

But it remains a challenge to secure funding for psychedelic research. Government funding is limited, and pharmaceutical companies are often hesitant to invest because psychedelic-assisted therapy does not generally fit the traditional pharmaceutical model.

“It’s not something that a pharmaceutical company wants to pay for, because it’s not going to be a classic pharmaceutical,” said Walsh.

As a result, many researchers rely on private donations or venture capital. This makes it difficult to fund large-scale studies, says Farb, who has faced institutional obstacles researching microdosing for treatment-resistant depression.

“No one wants to be that first cautionary tale,” he said. “No one wants to invest a lot of money to do the kind of study that would be transparent if it didn’t work.”

Difficulties in clinical trials

But funding is not the only challenge. Sources also pointed to the difficulty of designing clinical trials for psychedelics.

In particular, it can be difficult to implement a blind trial process, given the potent effects of psychedelics. Double blind trials are the gold standard of clinical trials, where neither the person administering the drug or patient knows if the patient is receiving the active drug or placebo.

Health Canada also requires researchers to meet strict trial criteria, such as demonstrating that the benefits outweigh the risks, that the drug treats an ongoing condition with no other approved treatments, and that the drug’s effects exceed any placebo effect.

It is especially difficult to isolate the effects of psychedelics. Psychotherapy, for example, can play a crucial role in treatment, making it difficult to disentangle the role of therapy from the drugs.

Mayo, of the University of Calgary, worries the demands of clinical trial models are not practical given the limitations of Canada’s health-care system.

“The way we’re writing these clinical trials, it’s not possible within our existing health-care infrastructure,” she said. She cited as one example the expectation that psychiatrists in clinical trials spend eight or more hours with each patient.

Ethical issues

Psychedelics research can also raise ethical concerns, particularly where it involves individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions.

A 2024 study found that people who visited an emergency room after using hallucinogens were at a significantly increased risk of developing schizophrenia — raising concerns that trials could harm vulnerable participants.

Another problem is a lack of standardization in psychedelic therapy. “We haven’t standardized it,” said Mayo. “We don’t even know what people are being taught psychedelic therapy is.”

This concern was underscored in a 2015 clinical trial on MDMA in Canada, where one of the trial participants was subjected to inappropriate physical contact and questioning by two unlicensed therapists.

Mayo advocates for the creation of a regulatory body to standardize therapist training and prevent misconduct.

Others have raised concerns about whether the research exploits Indigenous knowledge or cultural practices.

“There’s no psychedelic science without Indigenous communities,” said Joseph Mays, a doctorate candidate at the University of Saskatchewan.

“Whether it’s medicalized or ceremonial, there’s a direct continuity with Indigenous practices.”

Mays is an advisor to the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative, which funnels psychedelic investments back to Indigenous communities. He believes those working with psychedelics must incorporate reciprocity into their work.

“If you’re using psychedelics in any way, it only makes sense that you would also have a commitment to fighting for the rights of [Indigenous] communities, which are still lacking basic necessities,” said Mays, suggesting that companies profiting from psychedelic medicine should contribute to Indigenous causes.

Despite these various challenges, sources remained optimistic that psychedelics would eventually be legalized — although not due to their work.

“It’s inevitable,” said Mays. “They’re already widespread, being used underground.”

Farb agrees. “A couple more research studies is not going to change the law,” he said. “Power is going to change the law.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

-

Alberta9 hours ago

Alberta9 hours agoGovernments in Alberta should spur homebuilding amid population explosion

-

Automotive1 day ago

Automotive1 day agoCanadians’ Interest in Buying an EV Falls for Third Year in a Row

-

Entertainment2 days ago

Entertainment2 days agoPedro Pascal launches attack on J.K. Rowling over biological sex views

-

conflict2 days ago

conflict2 days agoTrump tells Zelensky: Accept peace or risk ‘losing the whole country’

-

Alberta8 hours ago

Alberta8 hours agoLow oil prices could have big consequences for Alberta’s finances

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoPoilievre Campaigning To Build A Canadian Economic Fortress

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoAs PM Poilievre would cancel summer holidays for MP’s so Ottawa can finally get back to work

-

armed forces19 hours ago

armed forces19 hours agoYet another struggling soldier says Veteran Affairs Canada offered him euthanasia