Energy

Canada could have been an energy superpower. Instead we became a bystander

This article was originally published in a collected volume, Canada’s Governance Crisis, which outlines Canada’s policy paralysis across a wide range of government priorities. Read the full paper here.

From the MacDonald-Laurier Institute

By Heather Exner-Pirot

Government has imposed a series of regulatory burdens on the energy industry, creating confusion, inefficiency, and expense

Oil arguably remains the most important commodity in the world today. It paved the way for the industrialization and globalization trends of the post-World War II era, a period that saw the fastest human population growth and largest reduction in extreme poverty ever. Its energy density, transportability, storability, and availability have made oil the world’s greatest source of energy, used in every corner of the globe.

There are geopolitical implications inherent in a commodity of such significance and volume. The contemporary histories of Russia, Iran, Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq are intertwined with their roles as major oil producers, roles that they have used to advance their (often illiberal) interests on the world stage. It is fair to ask why Canada has never seen fit to advance its own values and interests through its vast energy reserves. It is easy to conclude that its reluctance to do so has been a major policy failure.

Canada has been blessed with the world’s third largest reserves of oil, the vast majority of which are in the oil sands of northern Alberta, although there is ample conventional oil across Western Canada and offshore Newfoundland and Labrador as well. The oil sands contain 1.8 trillion barrels of oil, of which just under 10 percent, or 165 billion barrels, are technically and economically recoverable with today’s technology. Canada currently extracts over 1 billion barrels of that oil each year.

The technology necessary to turn the oil sands into bitumen that could then be exported profitably really took off in the early 2000s. Buoyed by optimism of its potential, then Prime Minister Stephen Harper pronounced in July 2006 that Canada would soon be an “energy superproducer.” A surge of investment came to the oil sands during the commodity supercycle of 2000-2014, which saw oil peak at a price of $147/barrel in 2008. For a few good years, average oil prices sat just below $100 a barrel. Alberta was booming until it crashed.

Two things happened that made Harper’s prediction fall apart. The first was the shale revolution – the combination of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling that made oil from the vast shale reserves in the United States economical to recover. Until then, the US had been the world’s biggest energy importer. In 2008 it was producing just 5 million barrels of crude oil a day, and had to import 10 million barrels a day to meet its ravenous need. Shale changed that, and the US is now the world’s biggest oil producer, expecting to hit a production level of 12.4 million barrels a day in 2023.

For producers extracting oil from the oil sands, the shale revolution was a terrible outcome. Just as new major oil sands projects were coming online and were producing a couple of million barrels a day, our only oil customer was becoming energy self-sufficient.

Because the United States was such a reliable and thirsty oil consumer, it never made sense for Canada to export its oil to any other nation, and the country never built the pipeline or export terminal infrastructure to do so. Our southern neighbour wanted all we produced. But the cheap shale oil that flooded North America in the 2010s made that dependence a huge mistake as other markets would have proven to be more profitable.

If shale oil took a hatchet to the Canadian oil industry, the election of the Liberals in 2015 brought on its death by a thousand cuts. For the last eight years, federal policies have incrementally and cumulatively damaged the domestic oil and gas sector. With the benefit of hindsight in 2023, it is obvious that this has had major consequences for global energy security, as well as opportunity costs for Canadian foreign policy.

Once the shale revolution began in earnest, the urgency in the sector to be able to export oil to any other market than the United States led to proposals for the Northern Gateway, Energy East, and TMX pipelines. Opposition from Quebec and BC killed Energy East and Northern Gateway, respectively. The saga of TMX may finally end this year, as it is expected to go into service in late 2023, billions of dollars over cost and years overdue thanks to regulatory and jurisdictional hurdles.

Because Canada has been stuck selling all of its oil to the United States, it does so at a huge discount, known as a differential. That discount hit a staggering US$46 per barrel difference in October 2018, when WTI (West Texas Intermediate) oil was selling for $57 a barrel, but we could only get $11 for WCS (Western Canada Select). The lack of pipelines and the resulting differential created losses to the Canadian economy of $117 billion between 2011 and 2018, according to Frank McKenna, former Liberal New Brunswick Premier and Ambassador to the United States, and now Deputy Chairman of TD Bank.

The story is not dissimilar with liquefied natural gas (LNG). While both the United States and Canada had virtually no LNG export capacity in 2015, the United States has since grown to be the world’s biggest LNG exporter, helping Europe divest itself of its reliance on Russian gas and making tens of billions of dollars in the process. Canada still exports none, with regulatory uncertainty and slow timelines killing investor interest. In fact, the United States imports Canadian natural gas – which it buys for the lowest prices in the world due to that differential problem – and then resells it to our allies for a premium.

Canada’s inability to build pipelines and export capacity is a major problem on its own. But the federal government has also imposed a series of regulatory burdens and hurdles on the industry, one on top of the other, creating confusion, inefficiency, and expense. It has become known in Alberta as a “stacked pancake” approach.

The first major burden was Bill C-48, the tanker moratorium. In case anyone considered reviving the Northern Gateway project, the Liberal government banned oil tankers from loading anywhere between the northernmost point of Vancouver Island to the BC-Alaska border. That left a pathway only for TMX, which goes through Vancouver, amidst fierce local opposition. I have explained it to my American colleagues this way: imagine if Texas was landlocked, and all its oil exports had to go west through California, but the federal government banned oil tankers from loading anywhere on the Californian coast except through ports in San Francisco. That is what C-48 did in Canada.

Added to Bill C-48 was Bill C-69, known colloquially as the “no new pipelines” bill and now passed as the Impact Assessment Act, which has successfully deterred investment in the sector. It imposes new and often opaque regulatory requirements, such as having to conduct a gender-based analysis before proceeding with new projects to determine how different genders will experience them: “a way of thinking, as opposed to a unique set of prescribed methods,” according to the federal government. It also provides for a veto from the Environment and Climate Change Canada Minister – currently, Steven Guilbeault – on any new in situ oil sands projects or interprovincial or international pipelines, regardless of the regulatory agency’s recommendation.

The Alberta Court of Appeal has determined that the act is unconstitutional, and eight other provinces are joining in its challenge. But so far it is the law of the land, and investors are allergic to it.

Federal carbon pricing, and Alberta’s federally compatible alternative for large emitters, the TIER (Technology Innovation and Emissions Reduction) Regulation, was added next, though this regulation makes sense for advancing climate goals. It is the main driver for encouraging emission reductions, and includes charges for excess emissions as well as credits for achieving emissions below benchmark. It may be costly for producers, but from an economic perspective, of all the climate policies carbon pricing is the most efficient.

Industry has committed to their shareholders that they will reduce emissions; their social license and their investment attractiveness depends to some degree on it. The major oil sands companies have put forth a credible plan to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. One conventional operation in Alberta is already net zero thanks to its use of carbon capture technology. Having a predictable and recognized price on carbon is also providing incentives to a sophisticated carbon tech industry in Canada, which can make money by finding smart ways to sequester and use carbon.

In theory, carbon pricing should succeed in reducing emissions in the most efficient way possible. Yet the federal government keeps adding more policies on top of carbon pricing. The Canadian Clean Fuel Standard, introduced in 2022, mandates that fuel suppliers must lower the “lifecycle intensity” of their fuels, for example by blending them with biofuels, or investing in hydrogen, renewables, and carbon capture. This standard dictates particular policy solutions, causes the consumer price of fuels to increase, facilitates greater reliance on imports of biofuels, and conflicts with some provincial policies. It is also puts new demands on North American refinery capacity, which is already highly constrained.

The newest but perhaps most damaging proposal is for an emissions cap, which seeks to reduce emissions solely from the oil and gas sector by 42 percent by 2030. This target far exceeds what is possible with carbon capture in that time frame, and can only be achieved through a dramatic reduction in production. The emissions cap is an existential threat to Canada’s oil and gas industry, and it comes at a time when our allies are trying, and failing, to wean themselves off of Russian oil. The economic damage to the Canadian economy is hard to overestimate.

Oil demand is growing, and even in the most optimistic forecasts it will continue to grow for another decade before plateauing. Our European and Asian allies are already dangerously reliant on Russia and Middle Eastern states for their oil. American shale production is peaking, and will soon start to decline. Low investment levels in global oil exploration and production, due in part to ESG (environmental, social, and governance) and climate polices, are paving the way for shortages by mid-decade.

An energy crisis is looming. Canada is not too late to be the energy superproducer the democratic world needs in order to prosper and be secure. We need more critical minerals, hydrogen, hydro, and nuclear power. But it is essential that we export globally significant levels of oil and LNG as well, using carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) wherever possible.

Meeting this goal will require a very different approach than the one currently taken by the federal government: it must be an approach that encourages growth and exports even as emissions are reduced. What the government has done instead is deter investment, dampen competitiveness, and hand market share to Russia and OPEC.

Heather Exner-Pirot is Director of Energy, Natural Resources and Environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Alberta

National Crisis Approaching Due To The Carney Government’s Centrally Planned Green Economy

From Energy Now

By Ron Wallace

Welcome to the Age of Ottawa’s centrally planned green economy.

On November 13, 2025, the Carney government announced yet another round of projects to be referred to the newly created Major Projects Office (MPO) established under the authority of the Building Canada Act (2025). That Office, designed to coordinate and streamline federal approvals for infrastructure projects deemed by Cabinet to be in the “national interest”. The announcement made scant reference to the fact that most of the referred projects had already received the regulatory permits required for construction or are, in several cases, already well under way.

Meanwhile, the aspirations of Alberta’s Premier Danielle Smith were not realized with a “Memorandum of Understanding” (MoU) signed with the Carney government before the 112th Grey Cup in Winnipeg. It remains to be seen if Canada and Alberta can in fact “create the circumstances whereby the oil and gas emissions cap would no longer be required” and if these negotiations will result in a “grand bargain” with the federal government. For its part, Alberta has signaled a willingness to change its industrial carbon tax program to encourage corporations to invest in emissions reduction projects while Alberta’s major energy producers have signalled that they are willing to consider carbon capture and methane reduction within an agreed industrial carbon pricing scheme. Notwithstanding concerns about its financial and technical viability, the Pathways Alliance Project appears to have become a cornerstone of Alberta’s negotiations with the federal government.

In early 2025 Premier Smith issued a list of nine demands accompanied by a six month ultimatum demanding the federal government roll back key elements of its climate policy. Designed to re-assert Alberta’s autonomy over natural resources, Smith’s core issues centered on the repeal of Bill C-69 (the “no new pipelines act) and Bill C-48 (the Oil Tanker Moratorium Act) scrapping the proposed Clean Electricity Regulations and abandonment of the net-zero automobile mandate. In face of a possible refusal by Ottawa to deal with these outstanding issues, Premier Smith launched a “Next Steps” panel as a province-wide consultation to “strengthen provincial sovereignty within Canada” – a process that could possibly lead to a referendum on Alberta’s future within Confederation.

Subsequently, in early October, Premier Smith also announced that her government, in collaboration with three pipeline industry partners, would advance an application to the Major Projects Office for a new oil pipeline from Alberta to a marine terminal on the northwest coast of British Columbia. The intent of the application is to have this new pipeline designated as a ‘project in the national interest’ to receive an accelerated review and approval timeline. Alberta is planning to submit that application in May 2026 to address the five criteria set by Ottawa for national interest determinations. Notably, the removal of what Premier Smith has termed ‘bad laws’ would be a prerequisite to construction of this proposed project.

As the Carney government continues its complex dance around these issues it remains to be seen how, or if, Smith’s demands for Canada to roll back federal legislation will be met. While Premier Smith staunchly advocated for the removal of what she termed to be the ‘bad laws’ standing in the way of the “ultimate approval” of a pipeline to the B.C. coast it remains to be seen if the Carney government will to accede to most, or even any, of these demands in ways that could clear the way for a new oil export pipeline from Alberta. At a time when the Carney government appears to be doubling down on its priority to reduce Canadian emissions it remains to be seen if Alberta can in fact increase oil production without increasing emissions.

Liberal MP Corey Hogan, who serves as parliamentary secretary to the Minister of Energy and Natural Resources the Honourable Tim Hodgson, noted that: “So as long as we can get to common understandings of what all of those mean, there’s not really a need for an emissions cap.” This ‘common understanding’ may signal a willingness by Ottawa to set aside the Trudeau government’s signature proposed oil and gas emissions cap in exchange for major carbon capture and storage projects in Alberta that would be combined with strong carbon pricing and methane regulations.

While this ‘common understanding’ may yet lead to a ‘grand bargain’ it would nevertheless effectively create two different classes of oil in Canada, each operating under different sets of regulations and different cost structures. Western Canada’s crude oil producers would be forced to shoulder costly and technically challenging decarbonization requirements in face of a federal veto over any new oil projects that weren’t ‘decarbonized.’ Canadian-produced oil would be faced with entering international export markets at a significant, if not ruinous, competitive disadvantage risking not only profitability but market share. Meanwhile, this hypocritical policy would allow eastern Canadian oil refiners to import ‘carbonized’ oil from countries with significantly looser environmental standards.

Carney’s November 2025 “Canada Strong” federal budget sets out $141.4 billion in new spending over five years with a projected $78.3 billion deficit for 2025–26. As Jack Mintz points out, while that budget claims to be “spending less to invest more”, annual capital spending will double from $30 billion a year to $60 billion a year over five years:

“… as federal program spending, which excludes interest on debt, is forecast to rise by 16 per cent from $490 billion this fiscal year to $568 billion in 2029-30. During the current year alone, the spending increase is a remarkable seven per cent. Public debt charges will soar by 43 per cent from $53 billion to $76 billion due to growing indebtedness and higher interest rates. No surprise there. Deficits — $78 billion this year alone — accumulate by a whopping $320 billion over five years.”

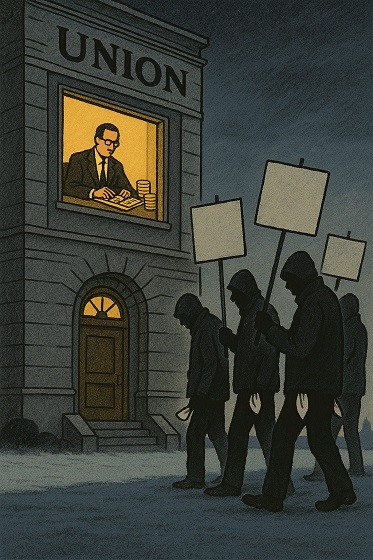

Since 2015 Canada has experienced a flight of investment capital approaching CAD$650 billion due to lost, or deferred, resource projects – particularly in the energy sector. While many economists recognize that Canada’s fiscal status may be worse than it appears, the Carney government is asking Canadians to ignore these figures while they implement industrial policies that, for all intents and purposes, represent a significant regression into central planning. The ‘modernization’ of the National Energy Board that began early in the Trudeau government’s mandate appears now to have been but a first step in the progressive centralization of control by the federal government. Gone are the days when an independent expert energy regulator made national interest determinations based upon cross-examined evidence presented in a public forum. Instead, a cabinet cloaked in confidentiality that is clearly inclined toward emissions reduction as its paramount consideration, will now determine and select projects.

This process of centralized decision-making represents a dilemma that confronts not just Premier Smith but the entire Canadian energy sector. The emerging financial debacle in the Canadian EV battery and vehicular manufacturing market is but one example of how centrally planned criteria designed to achieve a Net Zero economy will almost invariably lead to unanticipated, if not economically disastrous, results.

In short, the “green economy” is not working. The Fraser Institute noted that while Federal spending on the green economy surged from $600 million in 2014/15 to $23 billion in 2024/25, a nearly 40-fold increase, the green economy’s share of GDP rose only marginally from 3.1% in 2014 to 3.6% in 2023. Moreover, promised “green jobs” have not materialized at scale while traditional energy sectors vital to Alberta’s and the Canadian GDP have been actively constrained.

This economic reality has apparently not yet dawned in Ottawa. As Gwyn Morgan points out, Prime Minister Carney who, in 2021 with Michael Bloomberg, launched the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), has not changed his determination to hike Canadian carbon taxes, proposing to increase the industrial levy from $80 to $170/ton by 2030. GFANZ was created to align global financial institutions with net-zero emissions targets bringing together sector-specific alliances like the Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA) and the Net Zero Asset Managers (NZAM). However, early in 2025 GFANZ faced significant challenges as major U.S. banks exited the NZBA followed by the Net-Zero Insurance Alliance (NZIA) that disbanded entirely in 2024 after a wave of member withdrawals. GFANZ was forced to undergo a strategic restructuring in January 2025 to shift from a coalition-of-alliances to a more open, standalone platform focused on mobilizing capital for the low-carbon transition through pragmatic climate financing. ‘Pragmatic’ indeed.

While Carney’s GFANZ has effectively imploded, his government ignores developing new realities in climate policy by continuing to implement the Trudeau government’s green agenda with programs like the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. That program contains a plethora of ‘green economy’ measures designed to reduce carbon emissions in parallel with the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan that commits Canada to reducing greenhouse gases (GHG) to achieve net-zero by 2050.

These policies ignore the recent change of mind by thought-leaders like Bill Gates who acknowledges that “climate change, disease, and poverty are all major problems we should deal with them in proportion to the suffering they cause.” This aligns his thinking with that of Bjorn Lomborg who states:

“Climate change demands action, but not at the expense of poverty reduction. Rich governments should invest in long-overdue R&D for breakthrough green technologies — affordable, reliable alternatives that everyone, rich and poor alike, will adopt. That is how we can solve climate without sacrificing the vulnerable. More countries, including Canada, need to get on board with the mission of returning the World Bank to focusing on poverty. Raiding development funds for climate initiatives isn’t just misguided. It’s an affront to human suffering.”

Philip Cross also expressed hope that 2025 may yet represent a “turning point in a return to sanity in public policy:”

“Nowhere is the change more evident than in attitudes to green energy policies, once the rallying cry for left-wing parties in North America. Support has collapsed for three pillars of green energy advocacy: building electric vehicles to eliminate our need for oil pipelines and refineries; using the financial clout of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance to force firms to eliminate carbon emissions; and legally mandating the shift from fossil fuels to green energy.”

Nonetheless, Prime Minister Carney appears resolute in the belief that Canadian policies for Net Zero are not hobbling investment in the energy sector while choosing to ignore alternative regulatory and investment tools that could make a material difference for the economy. Carney also appears to ignore major Canadian firms like TC Energy that have re-directed investments of $8.5 billion into the U.S. as they cite significant concerns about the Canadian regulatory structure. Similarly, Enbridge has advocated for “significant energy policy changes” in Canada while focussing attention not on new export pipelines but instead to incrementally upgrade capacity within its existing Mainline system network.

Canada’s destiny as a ‘decarbonized energy superpower’ will be largely determined by the serious economic consequences that will result from a sustained ideological push into ‘clean energy’. That said, will this be accomplished by a chaotic, ever-more centralized process of decision making, masquerading as a coherent national energy policy?

Conclusion

As Gwyn Morgan has succinctly written, it remains to be seen if the Carney government will be willing to make a “climate climbdown” in face of the reality that net zero goals are being broadly abandoned globally or will they continue to sacrifice the Canadian economy to single-minded, unrealistic or unattainable, goals for emissions reduction?

To date none of the projects referred by the Carney government to the Major Projects Office has been designated as ‘being in the national interest’. Moreover, the Alberta bitumen pipeline advocated by Premier Smith has not yet appeared on any list. Nonetheless, she apparently remains resolute in maintaining negotiations with Ottawa stating: “Currently, we are working on an agreement with the federal government that includes the removal, carve out or overhaul of several damaging laws chasing away private investment in our energy sector, and an agreement to work towards ultimate approval of a bitumen pipeline to Asian markets.”

As Alberta’s ultimatums and deadlines to Ottawa pass, it would be reasonable to question whether Premier Smith is, in fact, being confronted with the illusory freedom of a Hobson’s choice: Either Alberta must accept, at unprecedented cost, Ottawa’s determination to realize Net Zero or it will get nothing at all. While she may be seeking federal support to enable, or accelerate, construction of new pipelines, all Ottawa may be willing to concede is a promise to do better with an MoU that would ultimately impose massive costs for ‘decarbonization’ on Alberta while eastern Canada imports oil from other, less constrained, jurisdictions. Is this a “Grand Bargain?”

Budget 2025 has introduced a Climate Competitiveness Strategy for nuclear, hydro, wind and grid modernization that projects over CAD$1 trillion in spending over five years. It also reaffirms a commitment to increase carbon taxes by $80-$170/tonne for CO2-equivalent emissions by 2030. Since it appears committed to maintaining, or even expanding, Trudeau-era green legislation, some might question any commitments from the Carney government to enter into an even-handed debate on Canadian energy policies that are so critical to Alberta’s energy sector? As the Fraser Institute points out:

“The Canadian case shows an even greater mismatch between Ottawa’s COP commitments and its actual results. Despite billions spent by the federal government on the low-carbon economy (electric vehicle subsidies, tax credits to corporations, etc.), fossil fuel consumption increased 23 per cent between 1995 and 2024. Over the same period, the share of fossil fuels in Canada’s total energy consumption rose from 62.0 to 66.3 per cent.”

While the creation of the MPO may give the appearance of accelerating projects deemed to be in the national interest it nonetheless requires a circumvention of an existing legislative base. This approach further enhances a centrally-planned economy and presupposes that more, not less, bureaucracy will somehow make Canada an “energy superpower”.

Canada continues to overlook rising economic challenges while pursuing climate goals with inconsistent policies. As such, it risks becoming an outlier in energy policy at a time when the world is beginning to recognize the immense costs and implausibility of implementing policies for Net Zero.

Premier Danielle Smith may yet face a pivotal moment in Alberta’s, and possibly Canadian, history. If Ottawa’s past performance is but a prologue, predictions of a happy outcome may require a significant dose of optimism.

Ron Wallace is a former Member of the National Energy Board.

Business

Carney doubles down on NET ZERO

If you only listened to the mainstream media, you would think Justin Trudeau’s carbon tax is long gone. But the Liberal government’s latest budget actually doubled down on the industrial carbon tax.

While the consumer carbon tax may be paused, the industrial carbon tax punishes industry for “emitting” pollution. It’s only a matter of time before companies either pass the cost of the carbon tax to consumers or move to a country without a carbon tax.

Dan McTeague explains how Prime Minister Carney is doubling down on net zero scams.

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoLack of adequate health care pushing Canadians toward assisted suicide

-

National1 day ago

National1 day agoWatchdog Demands Answers as MP Chris d’Entremont Crosses Floor

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoATA Collect $72 Million in Dues But Couldn’t Pay Striking Teachers a Dime

-

Artificial Intelligence2 days ago

Artificial Intelligence2 days agoAI Faces Energy Problem With Only One Solution, Oil and Gas

-

Artificial Intelligence1 day ago

Artificial Intelligence1 day agoAI seems fairly impressed by Pierre Poilievre’s ability to communicate

-

Alberta7 hours ago

Alberta7 hours agoCalgary mayor should retain ‘blanket rezoning’ for sake of Calgarian families

-

Media1 day ago

Media1 day agoBreaking News: the public actually expects journalists to determine the truth of statements they report

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoLiberal’s green spending putting Canada on a road to ruin