Break The Needle

B.C. crime survey reveals distrust in justice system, regional divides

By Alexandra Keeler

In late August, the RCMP seized nearly 40 kilograms of illegal drugs and half-a-million dollars in cash from a home in Prince George, B.C., while responding to a break-and-enter call.

The RCMP linked the drug operation to organized crime and said it was one of the largest busts in the history of the 80,000-person city, which is located in the B.C. heartland.

“It is obvious we can no longer ignore the effects of the B.C. gang conflict in Prince George, as this is a clear indication that more than our local drug traffickers are using Prince George as a base of operations,” Insp. Darin Rappel, interim detachment commander for the Prince George RCMP, told local media at the time.

It is operations such as these that may be contributing to a perception among British Columbians — particularly those in northern parts of the province — that crime rates are rising.

A survey released Sept. 24 shows a majority of respondents believe B.C. crime rates are up — and often unreported — even though official crime data suggest the opposite.

The survey was commissioned by Save Our Streets, a coalition of more than 100 B.C. community and business groups that is calling for non-partisan, province-wide efforts to establish safer communities in the face of widespread mental health and addiction issues and lack of confidence in the justice system.

“I’m glad that we have our data,” said Jess Ketchum, co-founder of Save Our Streets. “[N]ow we can show that, ‘Look, 88 per cent of the public in B.C. believe that crime is going unreported.’”

“[And] the reason that it’s going unreported is that they’ve lost faith in the justice system,” he said.

‘Revolving doors’

Fifty-five per cent of the 1,200 British Columbians who participated in the survey said they believed criminal activity had increased over the past four years. The survey did not specify types of crime, though it mentioned concerns about violence against employees, vandalism and theft.

But crime data tells a different story. B.C. crime rates fell eight per cent during the years 2020 to 2023, according to Statistics Canada.

Underreporting of crime may partly explain the trend. A 2019 nationwide Statistics Canada survey of individuals aged 15 years and older showed only 29 per cent of violent and non-violent incidents were reported to police. Victims often cited the crime being minor, not important, or no one being harmed as reasons for not reporting.

What is clear is many British Columbians perceive crime is being underreported: 88 per cent of all survey respondents said they believe many crimes go unreported.

|

Perceptions of Crime & Public Safety in British Columbia. Online survey commissioned by Save Our Streets, conducted by Research Co. with a representative sample of 1,200 British Columbians, Sept 9-12, 2024. (Graphic: Alexandra Keeler)

Mario Canseco, president of Research Co., the public research company that conducted the Save Our Streets survey, attributes the gap between actual and perceived crime rates to the heightened visibility of mental health and addiction issues in the media.

“You look at the reports, you watch television news, listen to the radio, or read the newspaper, and you see that something happened, or that there was a high-profile attack,” said Canseco. “That leads people to believe that things are going badly.”

Survey respondents, though, attributed the lack of crime reporting to a lack of confidence in the justice system, with 75 per cent saying they believe an inadequate court system is to blame. Eighty-seven per cent said they supported bail reform to keep repeat offenders in custody while awaiting trial.

“There was support [in the survey results] for judicial reform that would allow for steps to resolve the revolving doors of the justice system when it comes to repeat offenders,” said Ketchum.

Cowboys

The survey highlighted regional differences in perceptions of B.C. crime rates and views on whether addiction-related crime ought to be addressed as a public health or law enforcement issue.

Respondents from Northern B.C., Prince George and the surrounding Cariboo region were more likely to say they believed criminal activity had increased than respondents from southern and coastal regions of the province.

Canseco suggests that drug use and associated crime are now becoming more apparent in smaller communities, as the drug crisis has spread beyond the major cities of Vancouver and Victoria. Residents of these communities may thus see these problems as more novel and alarming, he says.

Eighty-four per cent of respondents in Northern B.C. said they viewed opioid addiction as a health issue, while only 68 per cent of respondents in Prince George/Cariboo shared this perspective.

Respondents from Prince George/Cariboo exhibited the strongest preference for punitive measures regarding addiction and mental health, with nearly unanimous support for harsher penalties, bail reform and increased police presence.

“It’s one of the tougher areas in the province … somewhat more cowboys,” Ketchum said about Prince George and the Cariboo region, where his hometown of Quesnel is located. “I think there’s less tolerance.”

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis, or donate to our journalism fund.

Differences in each region’s demographic makeup may also help to explain differing sentiments.

Northern B.C. has the highest concentration of B.C.’s Indigenous population, with about 17 per cent of the population identifying as Indigenous, versus eight per cent in Prince George.

Indigenous communities tend to emphasize addiction as a health issue rooted in historical trauma and social inequities, and prefer community-based healing over punitive measures. Indigenous communities are also frequently distrustful of the RCMP, given its history of being used to extend colonial control.

A majority of all survey respondents favoured investing in mental health facilities, drug education campaigns and rehabilitation over harm-reduction strategies such as safer supply programs, supervised injection sites and drug decriminalization.

“People want to see a more holistic approach [to the drug crisis],” said Canseco. “[T]he voter who hasn’t been exposed to something like [harm reduction], and who may be reacting to what they see on social media, is having a harder time understanding whether this is actually going to help.”

“I was pleased to see the level of support for more investments in recovery, more investments in treatment, around the province,” said Ketchum.

But Ketchum says the preference of some respondents for punitive approaches to B.C. crime rates – particularly in the province’s more northern regions — worries him.

“I believe that if governments don’t respond adequately now, and this is allowed to escalate, that there’ll be more and more instances of people taking these things into their own hands.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle. Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Break The Needle

Why psychedelic therapy is stuck in the waiting room

There is mounting evidence of psychedelics’ effectiveness at treating mental disorders. But researchers face obstacles conducting rigorous studies

In a move that made international headlines, America’s top drug regulator denied approval last year for psychedelic-assisted therapy to treat post-traumatic stress disorder.

In its decision, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration cited concerns about study design and inadequate evidence to assess the benefits and harms of using the drug MDMA.

The decision was a significant setback for psychedelics researchers and veterans’ groups who had been advocating for the therapy to be approved. It is also reflective of a broader challenge faced by researchers keen to validate the therapeutic potential of psychedelics.

“Sometimes I feel like it’s death by 1,000 paper cuts,” said Leah Mayo, a researcher at the University of Calgary.

“If the regulatory burden were a little bit less, that would be helpful,” added Mayo, who holds the Parker Psychedelics Research Chair at the Psychedelic and Cannabinoid Therapeutics Lab. The lab develops new treatments for mental health disorders using psychedelics and cannabinoids.

Sources say the weak research body behind psychedelics is due to a complex interplay of factors. But they would like to see more research conducted to make psychedelics more accessible to people who could benefit from them.

“If you want [psychedelics] to work within existing health-care infrastructure, you have to play by [Canadian research] rules,” said Mayo.

“Therapy has to be reproducible, it has to be evidence-based, it has to be grounded in reality.”

Psychedelics in Canada

Psychedelics are hallucinogenic substances such as psilocybin, MDMA and ketamine that alter people’s perceptions, mood and thought processes. Psychedelic therapy involves the use of psychedelics in guided sessions with therapists to treat mental health conditions.

Psychedelics are generally banned for possession, production and distribution in Canada. However, two per cent of Canadians consumed hallucinogens in 2019, according to the latest Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey. Psychedelics are also used in Canada and abroad in unregulated clinics and settings to treat conditions such as substance use disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and various mental disorders.

“The cat’s out of the bag, and people are using this,” said Zachary Walsh, a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of British Columbia.

Within Canada, there are three ways for psychedelics to be accessed legally.

The federal health minister can approve their use for medical, scientific or public interest purposes. Health Canada runs a Special Access Program that allows doctors to request the use of unapproved drugs for patients with serious conditions that have not responded to other treatments. And Health Canada can approve psychedelics for use in clinical trials.

Researchers interested in conducting clinical trials involving psychedelics face significant hurdles.

“There’s been a concerted effort — and it’s just fading now — to mischaracterize the risks of these substances,” said Walsh, who has conducted several studies on the therapeutic uses of psychedelics. These include studies on MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD, and the effects of microdosing psilocybin on stress, anxiety and depression.

This Substack is reader-supported.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The U.S. government demonized psychedelic substances during its War on Drugs in the 1970s, exaggerating their risks and blocking research into their medical potential. Influenced by this war, Canada adopted similar tough-on-drugs policies and restricted research.

Today, younger researchers are pushing forward.

“New ideas really come into the forefront when the people in charge of the old ideas retire and die,” said Norman Farb, an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Toronto.

But it remains a challenge to secure funding for psychedelic research. Government funding is limited, and pharmaceutical companies are often hesitant to invest because psychedelic-assisted therapy does not generally fit the traditional pharmaceutical model.

“It’s not something that a pharmaceutical company wants to pay for, because it’s not going to be a classic pharmaceutical,” said Walsh.

As a result, many researchers rely on private donations or venture capital. This makes it difficult to fund large-scale studies, says Farb, who has faced institutional obstacles researching microdosing for treatment-resistant depression.

“No one wants to be that first cautionary tale,” he said. “No one wants to invest a lot of money to do the kind of study that would be transparent if it didn’t work.”

Difficulties in clinical trials

But funding is not the only challenge. Sources also pointed to the difficulty of designing clinical trials for psychedelics.

In particular, it can be difficult to implement a blind trial process, given the potent effects of psychedelics. Double blind trials are the gold standard of clinical trials, where neither the person administering the drug or patient knows if the patient is receiving the active drug or placebo.

Health Canada also requires researchers to meet strict trial criteria, such as demonstrating that the benefits outweigh the risks, that the drug treats an ongoing condition with no other approved treatments, and that the drug’s effects exceed any placebo effect.

It is especially difficult to isolate the effects of psychedelics. Psychotherapy, for example, can play a crucial role in treatment, making it difficult to disentangle the role of therapy from the drugs.

Mayo, of the University of Calgary, worries the demands of clinical trial models are not practical given the limitations of Canada’s health-care system.

“The way we’re writing these clinical trials, it’s not possible within our existing health-care infrastructure,” she said. She cited as one example the expectation that psychiatrists in clinical trials spend eight or more hours with each patient.

Ethical issues

Psychedelics research can also raise ethical concerns, particularly where it involves individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions.

A 2024 study found that people who visited an emergency room after using hallucinogens were at a significantly increased risk of developing schizophrenia — raising concerns that trials could harm vulnerable participants.

Another problem is a lack of standardization in psychedelic therapy. “We haven’t standardized it,” said Mayo. “We don’t even know what people are being taught psychedelic therapy is.”

This concern was underscored in a 2015 clinical trial on MDMA in Canada, where one of the trial participants was subjected to inappropriate physical contact and questioning by two unlicensed therapists.

Mayo advocates for the creation of a regulatory body to standardize therapist training and prevent misconduct.

Others have raised concerns about whether the research exploits Indigenous knowledge or cultural practices.

“There’s no psychedelic science without Indigenous communities,” said Joseph Mays, a doctorate candidate at the University of Saskatchewan.

“Whether it’s medicalized or ceremonial, there’s a direct continuity with Indigenous practices.”

Mays is an advisor to the Indigenous Reciprocity Initiative, which funnels psychedelic investments back to Indigenous communities. He believes those working with psychedelics must incorporate reciprocity into their work.

“If you’re using psychedelics in any way, it only makes sense that you would also have a commitment to fighting for the rights of [Indigenous] communities, which are still lacking basic necessities,” said Mays, suggesting that companies profiting from psychedelic medicine should contribute to Indigenous causes.

Despite these various challenges, sources remained optimistic that psychedelics would eventually be legalized — although not due to their work.

“It’s inevitable,” said Mays. “They’re already widespread, being used underground.”

Farb agrees. “A couple more research studies is not going to change the law,” he said. “Power is going to change the law.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

There’s No Such Thing as a “Safer Supply” of Drugs

By Adam Zivo

Sweden, the U.K., and Canada all experimented with providing opioids to addicts. The results were disastrous.

[This article was originally published in City Journal, a public policy magazine and website published by the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. We encourage our readers to subscribe to them for high-quality analysis on urban issues]

Last August, Denver’s city council passed a proclamation endorsing radical “harm reduction” strategies to address the drug crisis. Among these was “safer supply,” the idea that the government should give drug users their drug of choice, for free. Safer supply is a popular idea among drug-reform activists. But other countries have already tested this experiment and seen disastrous results, including more addiction, crime, and overdose deaths. It would be foolish to follow their example.

The safer-supply movement maintains that drug-related overdoses, infections, and deaths are driven by the unpredictability of the black market, where drugs are inconsistently dosed and often adulterated with other toxic substances. With ultra-potent opioids like fentanyl, even minor dosing errors can prove fatal. Drug contaminants, which dealers use to provide a stronger high at a lower cost, can be just as deadly and potentially disfiguring.

Because of this, harm-reduction activists sometimes argue that governments should provide a free supply of unadulterated, “safe” drugs to get users to abandon the dangerous street supply. Or they say that such drugs should be sold in a controlled manner, like alcohol or cannabis—an endorsement of partial or total drug legalization.

But “safe” is a relative term: the drugs championed by these activists include pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl, hydromorphone (an opioid as potent as heroin), and prescription meth. Though less risky than their illicit alternatives, these drugs are still profoundly dangerous.

The theory behind safer supply is not entirely unreasonable, but in every country that has tried it, implementation has led to increased suffering and addiction. In Europe, only Sweden and the U.K. have tested safer supply, both in the 1960s. The Swedish model gave more than 100 addicts nearly unlimited access through their doctors to prescriptions for morphine and amphetamines, with no expectations of supervised consumption. Recipients mostly sold their free drugs on the black market, often through a network of “satellite patients” (addicts who purchased prescribed drugs). This led to an explosion of addiction and public disorder.

Most doctors quickly abandoned the experiment, and it was shut down after just two years and several high-profile overdose deaths, including that of a 17-year-old girl. Media coverage portrayed safer supply as a generational medical scandal and noted that the British, after experiencing similar problems, also abandoned their experiment.

While the U.S. has never formally adopted a safer-supply policy, it experienced something functionally similar during the OxyContin crisis of the 2000s. At the time, access to the powerful opioid was virtually unrestricted in many parts of North America. Addicts turned to pharmacies for an easy fix and often sold or traded their extra pills for a quick buck. Unscrupulous “pill mills” handed out prescriptions like candy, flooding communities with OxyContin and similar narcotics. The result was a devastating opioid epidemic—one that rages to this day, at a cumulative cost of hundreds of thousands of American lives. Canada was similarly affected.

The OxyContin crisis explains why many experienced addiction experts were aghast when Canada greatly expanded access to safer supply in 2020, following a four-year pilot project. They worried that the mistakes of the recent past were being made all over again, and that the recently vanquished pill mills had returned under the cloak of “harm reduction.”

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Most Canadian safer-supply prescribers dispense large quantities of hydromorphone with little to no supervised consumption. Patients can receive up to 40 eight-milligram pills per day—despite the fact that just two or three are enough to cause an overdose in someone without opioid tolerance. Some prescribers also provide supplementary fentanyl, oxycodone, or stimulants.

Unfortunately, many safer-supply patients sell or trade a significant portion of these drugs—primarily hydromorphone—in order to purchase more potent illicit substances, such as street fentanyl.

The problems with safer supply entered Canada’s consciousness in mid-2023, through an investigative report I wrote for the National Post. I interviewed 14 addiction physicians from across the country, who testified that safer-supply diversion is ubiquitous; that the street price of hydromorphone collapsed by up to 95 percent in communities where safer supply is available; that youth are consuming and becoming addicted to diverted safer-supply drugs; and that organized crime traffics these drugs.

Facing pushback, I interviewed former drug users, who estimated that roughly 80 percent of the safer-supply drugs flowing through their social circles was getting diverted. I documented dozens of examples of safer-supply trafficking online, representing tens of thousands of pills. I spoke with youth who had developed addictions from diverted safer supply and adults who had purchased thousands of such pills.

After months of public queries, the police department of London, Ontario—where safer supply was first piloted—revealed last summer that annual hydromorphone seizures rose over 3,000 percent between 2019 and 2023. The department later held a press conference warning that gangs clearly traffic safer supply. The police departments of two nearby midsize cities also saw their post-2019 hydromorphone seizures increase more than 1,000 percent.

The Canadian government quietly dropped its support for safer supply last year, cutting funding for many of its pilot programs. The province of British Columbia (the nexus of the harm-reduction movement) finally pulled back support last month, after a leaked presentation confirmed that safer-supply drugs are getting sold internationally and that the government is investigating 60 pharmacies for paying kickbacks to safer-supply patients. For now, all safer-supply drugs dispensed within the province must be consumed under supervision.

Harm-reduction activists have insisted that no hard evidence exists of widespread diversion of safer-supply drugs, but this is only because they refuse to study the issue. Most “studies” supporting safer supply are produced by ideologically driven activist-scholars, who tend to interview a small number of program enrollees. These activists also reject attempts to track diversion as “stigmatizing.”

The experiences of Sweden, the United Kingdom, and Canada offer a clear warning: safer supply is a reliably harmful policy. The outcomes speak for themselves—rising addiction, diversion, and little evidence of long-term benefit.

As the debate unfolds in the United States, policymakers would do well to learn from these failures. Americans should not be made to endure the consequences of a policy already discredited abroad simply because progressive leaders choose to ignore the record. The question now is whether we will repeat others’ mistakes—or chart a more responsible course.

Our content is always free –

but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

-

conflict2 days ago

conflict2 days agoZelensky Alleges Chinese Nationals Fighting for Russia, Calls for Global Response

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoAn In-Depth Campaign Trail “Interview” With Pierre Poilievre

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoHarper Endorses Poilievre at Historic Edmonton Rally: “This Crisis Was Made in Canada”

-

John Stossel1 day ago

John Stossel1 day agoGovernment Gambling Hypocrisy: Bad Odds and No Competition

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

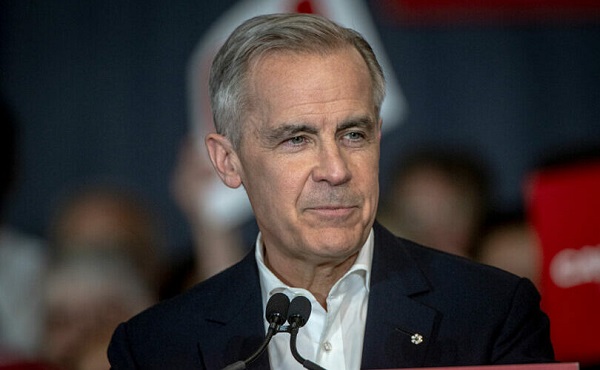

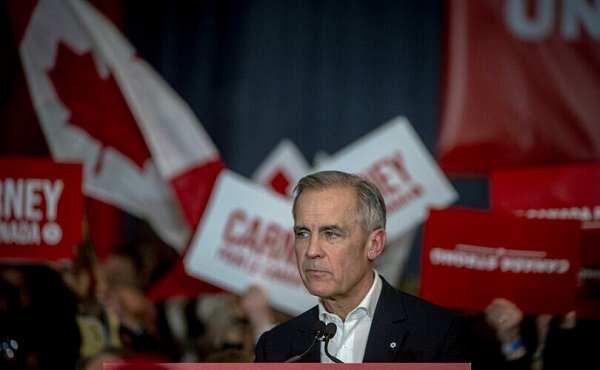

2025 Federal Election2 days agoMark Carney’s radical left-wing, globalist record proves he is Justin Trudeau 2.0

-

2025 Federal Election17 hours ago

2025 Federal Election17 hours agoFifty Shades of Mark Carney

-

2025 Federal Election1 day ago

2025 Federal Election1 day agoMark Carney pledges another $150 million for CBC ahead of federal election

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta’s embrace of activity-based funding is great news for patients