Censorship Industrial Complex

Australian politicians attack Elon Musk for refusing to remove video of Orthodox bishop’s stabbing

Photo by Leon Neal/Getty Images

From LifeSiteNews

By David James

The video is available on YouTube but Australia’s political class is singling out and waging war on X owner Elon Musk for his refusal to delete footage of the stabbing of Orthodox Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel.

In a demonstration of governmental overreach the Australian prime minister, Anthony Albanese, has attacked Elon Musk, the owner of X (formerly Twitter) for not acceding to demands to put a worldwide ban on video footage of an attempted stabbing of a bishop in a Sydney church.

Albanese is not alone; virtually the entire Australian political class has joined in the attack. Tanya Plibersek, minister for Environment and Water called Musk an “egotistical billionaire.” Greens senator Sarah Hanson-Young described him as a “narcissistic cowboy.” Albanese chimed in by describing him as an “arrogant billionaire who thinks he’s above the law.”

Senator Jacqui Lambie went as far as suggesting that Musk be “jailed” for his refusal to bend to the demands of the Australian government.

In response to Lambie’s comments, Musk declared her to be an “enemy of the people of Australia,” agreeing with another social media user who suggested it should be Lambie, not Musk, who belongs in jail.

This Australian Senator should be in jail for censoring free speech on X. https://t.co/vnYvBjpXav

— Rothmus 🏴 (@Rothmus) April 23, 2024

The right wing Liberal-National coalition was only slightly less aggressive saying Musk was offering an “insulting and offensive argument” in his refusal to remove graphic footage of the stabbing. How Musk saying that posts should not be taken down is “insulting and offensive” was not explained.

The victim of the attack, Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel, an Iraqi-born Assyrian Australian prelate who is head of the Eastern Christ the Good Shepherd Church, has displayed a maturity and moral virtue conspicuously lacking in the political arena. Emmanuel recorded a message saying that he loved his assailant, and that he wanted the video to stay online, urging people not to respond to violence with violence.

After the incident there were riots outside the church, resulting in 51 officers sustaining injuries. A 16-year-old boy has been arrested and charged with a religiously motivated terrorist attack.

The court battle between the Australian government and Musk is being characterised as a contest between free speech and the government’s role in protecting people. Certainly for Musk it is very much about protecting free speech.

That formulation is inaccurate. There is no effective protection of free speech in Australia, unlike the US, which has the First Amendment of the Constitution. The Federal government is currently preparing a misinformation and disinformation bill to force social media companies only to allow content of which the government approves.

As Senator Ralph Babet of the United Australia Party observes it is a “censorship agenda” that will be pushed no matter which party is in power. “The office of the eSafety commissioner was created under the Liberal Party and is now being emboldened by the Labor Party,” he writes.

The public battle with Musk is better seen as an attempt by the Australian government to control what is on the internet. The newly appointed eSafety commissioner, Julie Inman-Grant directed X to remove the posts, but X had only blocked them from access in Australia pending a legal challenge. The government then demanded that the posts be removed world-wide.

That the Australian political class thinks it has the right to issue edicts in countries where it has no legal jurisdiction is a demonstration of the lack of clarity in their thinking, and the intensity of their obsession with censoring.

Musk accurately characterised the situation in a post: “Should the eSafety Commissar (an unelected official) in Australia have authority over all countries on Earth?” It seems that many Australian politicians think the answer to that question is “Yes.”

The childish personal attacks on Musk, typical ad hominem attacks (going at the person rather than the argument) are revealing. What does the fact that Musk is a billionaire have to do with the legal status of the posts? Does having a lot of money somehow disqualify him from having a position?

If he is “egotistical” or “arrogant” what does that have to do with his logical or legal claims? How does exposing Musk as a narcissistic cowboy” have any relevance to him allowing content on the platform? Wouldn’t a narcissist be more likely to restrict content? The suspicion is that the politicians are resorting to such abuse because they have no argument.

The Australian government’s attack on Musk, which borders on the absurd, is just one of many being directed at X. An especially dangerous initiative is coming from the European Union’s Digital Services Act, which can apply fines of up to 6 per cent of the worldwide annual turnover, a ridiculously punitive amount. The United Kingdom’s communications regulator, Ofcom is even worse. It will have powers to fine companies up to 10 per cent of their global turnover.

Western governments are mounting an all out push to censor the internet, and Australia’s aggressive move is just part of that. What is never considered by governments and bureaucrats is the cost of such censorship.

The benefits of “protecting” people are always overstated and inevitably infantilize the population. The price is a degradation of social institutions and a legal system that does not apply equally to the citizenry and to the government. It is a step towards tyranny: rule by law rather than rule of law.

Censorship Industrial Complex

Canadian university censors free speech advocate who spoke out against Indigenous ‘mass grave’ hoax

From LifeSiteNews

Dr. Frances Widdowson was arrested and given a ticket at the University of Victoria campus after trying to engage in conversation about ‘the disputed claims of unmarked graves in Kamloops.’

A Canadian academic who spoke out against claims there are mass unmarked graves of kids on former Indigenous residential schools, and who was arrested on a university campus as a result for trespassing, is fighting back with the help of a top constitutional group.

Dr. Frances Widdowson was arrested and given a ticket on December 2, 2025, at the University of Victoria (UVic) campus after trying to engage in conversation about “the disputed claims of unmarked graves in Kamloops,” noted the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms (JCCF) in a recent news release.

According to the JCCF, Widdowson was trying to initiate a “good faith” conversation with people on campus, along with the leader of OneBC provincial party, Dallas Brodi.

“My arrest at the University of Victoria is an indication of an institution that is completely unmoored from its academic purpose,” said Widdowson in a statement made available to LifeSiteNews.

She added that the “institution” has been “perpetuating the falsehood” of the remains of 215 children “being confirmed at Kamloops since 2021, and is intent on censoring any correction of this claim.”

“This should be of concern for everyone who believes that universities should be places of open inquiry and critical thinking, not propaganda and indoctrination,” she added.

UVic had the day before Widdowson’s arrest warned on its website that those in favor of free speech were “not permitted to attend UVic property for the purpose of speaking publicly.”

Despite the warning, Widdowson, when she came to campus, was met with some “100 aggressive protesters assembled where she intended to speak at Petch Fountain,” noted the JCCF.

The protesters consisted of self-identified Communists, along with Antifa-aligned people and Hamas supporters.

When Widdowson was confronted by university security, along with local police, she was served with a trespass notice.

“When she declined to leave, she was arrested, detained for about two hours, and charged under British Columbia’s Trespass Act—an offence punishable by fines up to $2,000 or up to six months’ imprisonment,” said the JCCF.

According to Constitutional lawyer Glenn Blackett, UVic actions are shameful, as it “receives hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars annually while it facilitates the arrest of Canadians attempting to engage in free inquiry on campus.”

Widdowson’s legal team, with the help of the JCCF, will be defending her ticket to protect her “Charter-protected freedoms of expression and peaceful assembly.”

Widdowson served as a tenured professor at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta, before she was fired over criticism of her views on identity politics and Indigenous policy, notes the JCCF. She was vindicated, however, as an arbitrator later found her termination was wrongful.

In 2021 and 2022, the mainstream media ran with inflammatory and dubious claims that hundreds of children were buried and disregarded by Catholic priests and nuns who ran some Canadian residential schools. The reality is, after four years, there have been no mass graves discovered at residential schools.

However, as the claims went unfounded, over 120 churches, most of them Catholic and many of them on Indigenous lands that serve the local population, have been burned to the ground, vandalized, or defiled in Canada since the spring of 2021.

Last year, retired Manitoba judge Brian Giesbrecht said Canadians are being “deliberately deceived by their own government” after blasting the former Trudeau government for “actively pursuing” a policy that blames the Catholic Church for the unfounded “deaths and secret burials” of Indigenous children.

As reported by LifeSiteNews, new private members’ Bill C-254, “An Act To Amend The Criminal Code” introduced by New Democrat MP Leah Gazan, looks to give jail time to people who engage in so-called “Denialism.” The bill would look to jail those who question the media and government narrative surrounding Canada’s “Indian Residential School system” that there are mass graves despite no evidence to support this claim.

Censorship Industrial Complex

Top constitutional lawyer warns against Liberal bills that could turn Canada into ‘police state’

From LifeSiteNews

‘Freedom in Canada is dying slowly and gradually, not by a single fell swoop, but by a thousand cuts,’ wrote John Carpay of the JCCF.

One of Canada’s top constitutional legal experts has warned that freedom in the nation is “dying slowly” because of a host of laws both passed and now proposed by the Liberal federal government of Prime Minister Mark Carney, saying it is “up to citizens” to urge lawmakers to reverse course.

In an opinion piece that was published in the Epoch Times on December 15, John Carpay, who heads the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms (JCCF), gave a bleak outlook on no less than six Liberal laws, which he warned will turn Canada into a “police state.”

“Freedom in Canada is dying slowly and gradually, not by a single fell swoop, but by a thousand cuts,” he wrote.

Carpay gave the example of laws passed in the United Kingdom dealing with freedom of online speech, noting how in Canada “too few Canadians have spoken out against the federal government gradually taking over the internet through a series of bills with innocuous and even laudable titles.”

“How did the United Kingdom end up arresting thousands of its citizens (more than 30 per day) over their Facebook, X, and other social media posts? This Orwellian nightmare was achieved one small step at a time. No single step was deemed worthy of fierce and effective opposition by British citizens,” he warned.

Carpay noted how UK citizens essentially let it happen that their rights were taken away from them via mass “state surveillance.”

He said that in Canada Bill C-11, also known as the Online Streaming Act, passed in 2023, “undermines net neutrality.” Bill C-11 mandates that Big Tech companies pay to publish Canadian content on their platforms. As a result, Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, blocked all access to news content in Canada.

“The Online Streaming Act undermines net neutrality (all online content being treated equally) and amounts to an aggressive expansion of government control over the internet and media companies. The CRTC now has broad power over what Canadians watch, hear, and access online, deciding what is discoverable, permissible, or even visible,” noted Carpay.

Carpay also warned about two recent bills before the House of Commons: Bill C-2, the Strong Borders Act, Bill C-8, and Bill C-9, as well as the Combating Hate Act.

He cautioned that Bill C-2, as it reads, “authorizes warrantless demands for subscriber data and metadata from online providers.”

“Bill C-2 should be called the Strong Surveillance Act, as it gives sweeping powers to a host of non-police government officials to conduct warrantless searches,” warned Carpay.

He observed how Bill C-2 would grant law enforcement “unprecedented powers to monitor Canadians’ digital activity,” without any “judicial oversight.”

“Any online service provider—including social media and cloud platforms, email domain hosts and even smaller service providers—would be compelled to disclose subscriber information and metadata,” he warned.

When it comes to Bill C-8, or The Critical Cyber Systems Protection Act, Carpay warned that if passed it would “allow government to kick Canadians off the internet.”

“The government’s pretext for the Critical Cyber Systems Protection Act is to ‘modernize’ Canada’s cybersecurity framework and protect it against any threats of ‘interference, manipulation, disruption or degradation,’” wrote Carpay.

“Sadly, it remains entirely unclear whether ‘disinformation’ (as defined by government) would constitute ‘interference, manipulation, disruption or degradation’.”

Lawyer warns new laws ‘grant government unprecedented control’

Bill C-9, the Combating Hate Act, has been blasted by constitutional experts as allowing empowered police and the government to go after those it deems have violated a person’s “feelings” in a “hateful” way.

Carpay, who has warned about this bill and others, noted that when it comes to Bill C-9, it affects Canadians’ right to religious freedom, as it “removes needed protection from religious leaders (and others) who wish to proclaim what their sacred scriptures teach about human sexuality.”

“Marc Miller, Minister of Canadian Identity and Culture, has stated publicly that he views certain Bible and Koran passages as hateful. Bill C-9 would chill free speech, especially on the internet where expression is recorded indefinitely, and particularly for activists, journalists, and other people expressing opinions contrary to government-approved narratives,” he wrote.

“This law also vastly increases the maximum sentences that could be imposed if a judge feels that the offence was ‘motivated by hatred,’ and creates new offences. It prohibits merely displaying certain symbols linked to hate or terrorism in public, and extends criminal liability to peaceful protest activity.”

Carpay said that both C-8 and C-9 together “collectively grant government unprecedented control over online speech, news, streaming services, and digital infrastructure.”

He said that the Liberal federal government is “transforming Canada’s centuries-old traditions of free speech and privacy rights into something revocable at the pleasure of the CRTC, politicians, and bureaucrats,” adding that Canadians need to wake up.

“Laziness and naivete are not valid reasons for failing to rise up (peacefully!) and revolt against all of these bills, which are slowly but surely turning Canada into a police state,” he wrote.

Carpay said that Canadians need to contact their MPs and “demand the immediate repeal of the Online Streaming Act and the Online News Act,” and “reject” the other bills before the House.

When it comes to Bill C-9, as reported by LifeSiteNews, the Canadian Constitution Foundation (CCF) launched a petition demanding that a Liberal government bill that would criminalize parts of the Bible dealing with homosexuality under Canada’s new “hate speech” laws be fully rescinded.

The amendments to Bill C-9 have been condemned by the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, who penned an open letter to the Carney Liberals, blasting the proposed amendment and calling for its removal.

-

Crime2 days ago

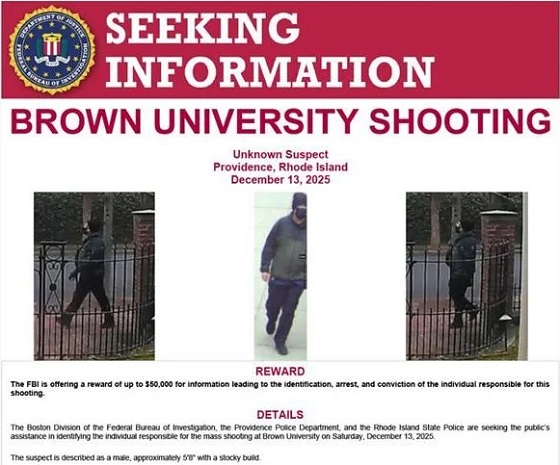

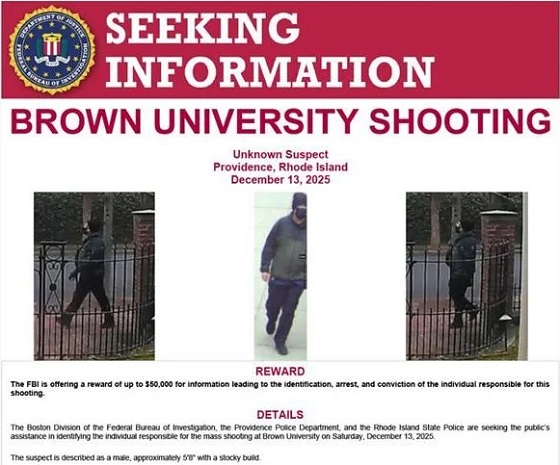

Crime2 days agoBrown University shooter dead of apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta’s new diagnostic policy appears to meet standard for Canada Health Act compliance

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoRFK Jr reversing Biden-era policies on gender transition care for minors

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoTrump signs order reclassifying marijuana as Schedule III drug

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoCanadian university censors free speech advocate who spoke out against Indigenous ‘mass grave’ hoax

-

Business21 hours ago

Business21 hours agoGeopolitics no longer drives oil prices the way it used to

-

Business21 hours ago

Business21 hours agoArgentina’s Milei delivers results free-market critics said wouldn’t work

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoEx-FDA Commissioners Against Higher Vaccine Standards Took $6 Million From COVID Vaccine Makers