Aristotle Foundation

At Toronto Metropolitan University medical school, some students are more equal than others

READ THE REALITY CHECK

By Bruce Pardy

A new Aristotle Foundation Reality Check from Queen’s University law professor Bruce Pardy details how Canada’s courts reinterpreted even the clear equality clause in the constitution to read in anti-individual “equity.” That hollowed out a founding Canadian principle of equality before the law.

|

|

|

Aristotle Foundation

We’re all “settlers”

By Mark Milke and Tom Flanagan

The settler-indigenous distinction is false. We all originated in Africa.

If Canadians care to understand why our country is increasingly fractured, one key driver is the notion that non-Indigenous Canadians — “settlers” as they are called — should be grateful to live anywhere in the Americas.

The “settler” label is mostly directed at those of British and European ancestry. But it can apply to anyone whose families arrived from anywhere — Africa, Asia, the Levant, the Pacific — who were not part of the prior waves of migration to the Americas.

According to the most recent scientific knowledge, human settlement in the Americas began about 15,000 to 20,000 years ago. These pioneers of settlement must have arrived from Asia by boat and hopscotched along the Pacific coast because the interior land was glaciated. They migrated as far south as modern-day Chile, but it is unknown how far inland they penetrated and whether they survived to merge with later migratory settlers.

Another wave of migration started around 13,000 years ago when an ice-free corridor opened through Alberta between the two great glaciers covering North America. This made it possible for people from the now submerged land of Beringia to move south through Alaska, Yukon and Alberta across North America.

Later, but at an unknown date, came the movement of the Dene-speaking peoples now living mostly in Alaska and Canada’s North (though the Tsuut’ina got to southern Alberta and the Navajo to the southwestern United States). Their languages still show traces of their relatively recent Siberian origins.

The Inuit migrated from Siberia across the Arctic to Greenland around AD 1000. Another group inhabited the Arctic starting around 2500 BC, but their relationship to the Inuit is uncertain.

In short, the Americas were settled in waves from Asia. Everyone alive today is descended from settlers. The latest “Indigenous” settlers arrived barely ahead of the first European settlers, the Vikings, who settled in Greenland and Newfoundland, and of Christopher Columbus, who started Spanish settlement in the Caribbean.

Singling out Europeans as “settlers” drives land acknowledgments, as well as demands for compensation and reconciliation. It plays on guilt about the actions of actors long since dead, while the concurrent demands for land, decision-making power and financial settlements occur on an open-ended basis. Internationally, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) also assumes the Indigenous vs. settler-colonial divide is valid.

Why does this matter? Because peaceful, relatively prosperous nation-states are not guaranteed to last. In fact, they’re the exception, not the rule. To make actual progress in unifying Canada as opposed to watching it break down and fragment into hundreds of inconsequential principalities (a separate Quebec, a separate Alberta, and multiple First Nations with state-like powers, of which there would be up to 200 in British Columbia alone), it is overdue to dissect these assumptions, and the related belief that Canadians have done little to make up for some of the wrongs done in history.

Language clarifications

Let’s begin with language.

The notion that some groups in the Americas have been here since “time immemorial” and thus are indigenous in the truest sense of that term is evolutionarily and historically false. The evolutionary origin of every human being lies in Africa, where Homo sapiens evolved as a distinct species about 315,000 years ago. Also, as Encyclopædia Britannica notes, “we were preceded for millions of years by other hominins, such as Ardipithecus, Australopithecus, and other species of Homo.”

The fact that all of us jointly link back to origins in Africa should be enough to stop using the “time immemorial” phrase, as well as any artificial distinction between those considered “Indigenous,” whose ancestors arrived in separate waves of migration separated by thousands of years, and those considered “settlers,” whose ancestors arrived during the last 500 years.

That some people’s ancestors beat others by 19,500 years or less to what we now call Canada does not create a permanent obligation on the part of later arrivals, or their progeny, to those whose families arrived first, just as Indigenous people today are not responsible for the actions of their own ancestors against other tribes over thousands of years. In the grand scheme of evolutionary time, all our ancestors’ lives were but a relative blip.

The ‘stolen land’ assertion

A stronger argument might be that later settlers owe the families of earlier settlers for stealing their land, which is a popular claim. However, that assertion ignores the multitude of treaties signed across Canada as well as the very approach by the colonial British and Sir John A. Macdonald that treaties were preferable to brazen conquest, as happened with other empires throughout history, including those now labelled Indigenous.

Further, that not every inch of Canada is covered by treaty still does not negate how the Canadian nation-state provided funds even to those First Nations not covered by treaty — in British Columbia, for example. Or how the 1982 constitutional amendments recognized Aboriginal and treaty rights, which are being constantly expanded by Canadian courts.

Moreover, the first Europeans and later British did not come to the Americas and “steal” a $2.5 trillion economy (Canada’s GDP in 2025). Rather, the earlier inhabitants were followed by French fur traders, Scottish explorers, Western farmers, Toronto financiers, Atlantic and Pacific fishermen, British and Asian workers, entrepreneurs in the 19th and 20th centuries and many other arrivals. All of them built Canada up. They did so with their own sweat, time and investment. That’s why farms feed Canadian families, mines provide steel for automobiles, natural gas and hydroelectricity heat homes, and skyscrapers can be built on First Nations reserves — because all “settlers” together made modern-day Canada possible.

Reconciliation considerations: Money flows and tax exemptions

Whenever reconciliation conversations begin, they inevitably assume “stolen” land as per above and ignore the significant past and present cash transfers as well as generous tax exemptions — many of which are not constitutionally required but exist as a result of the Indian Act, and thus could have been eliminated at any point in our collective history but were not.

Let’s follow the money. In 2013, one of us (Milke) authored the first comprehensive Fraser Institute report on the money spent in just the postwar world until 2012, at the federal and provincial levels, on Indigenous Canadians, including those once called “treaty Indians” but also others.

The results? In 2013 dollars (i.e., adjusted for inflation), in what was then known as the Department of Indian Affairs, spending on Canada’s Aboriginal peoples rose to almost $7.9 billion by 2011-12 from $79 million annually in 1946-47. That was an increase from $922 per Indigenous person per year to $9,056 — a rise of 882 per cent. By comparison, total federal program spending per person on all Canadians in the same years rose by 387 per cent. Of course, Indigenous Canadians are also eligible for and receive other government spending because they are Canadians.

Another one of us (Flanagan), updated that report and published several of his own for the Fraser Institute, which echoed the findings of the 2013 report on Aboriginal spending: ever-higher budgetary spending, plus eye-popping recent settlements of lawsuits. The largest of these was a $40 billion settlement in 2022 for children taken from reserves into foster care.

Spending on Indigenous programs and services in the 2024-25 budget was $32 billion, nearly triple what it was 10 years ago, even as outcomes have not measurably improved. Multiple multi-billion-dollar financial settlements also continue to be awarded every year, on top of the program and services funding itemized in the budget.

In addition to the child welfare settlement noted above, ponder a $10 billion settlement in 2023 related to the Robinson Huron Treaty (including individual payments of at least $110,000 per person), and an $8.5 billion agreement in 2025 to reform First Nations child and family services in Ontario, among others.

Much of the above spending on Indigenous peoples goes beyond traditional treaty and constitutional requirements. There is also much more to come. In the federal departments of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, beyond “routine” spending on Indigenous Canadians, several transfer programs explicitly provide funds to Indigenous Canadians and/or to support further claims upon the public purse.

That’s the spending side. Now the tax exemptions. In 2024, Flanagan published a report for the Aristotle Foundation on tax exemptions given to First Nations under Section 87 of the Indian Act. That’s the longstanding tax exemption for real and personal property owned by “Indians,” including employment income, on reserves. One incomplete estimate from 2015 quantified the value of those exemptions at roughly $1.3 billion a year.

At some point — we suggest now — all this should count towards the “paid” column in the reconciliation ledger.

The mistaken morality play

Financial matters aside, what drives one-sided reconciliation talk in Canada is not only the mistaken claim that those now labelled “Indigenous” have existed in the Americas from “time immemorial,” a creationist myth, but that pre-contact, First Nations were unlike all other human beings in history — peaceful with each other, and at one with the environment.

This image is ludicrously far from historical fact. Amerindians were environmentalists only because their small numbers limited the environmental damage they caused. And warfare was endemic among them. At the time of the American Revolution, the Iroquois were waging war to create an empire in Ontario and the American Midwest. The Ojibwe and Cree, originally woodland peoples, blasted their way onto the prairies after they got guns from the Hudson’s Bay Company. As late as 1870, the Cree and Blackfoot, both weakened by smallpox, fought a lethal battle near the site of modern Lethbridge, which is still remembered in tribal lore.

As the Romans said, Vae victis (“woe to the conquered.”) If the losers in intra-Indigenous wars did not die in battle, they were often tortured to death or enslaved. Slavery was practiced on a particularly large scale on the Pacific coast, where slaves could be put to work cutting wood. Indigenous slavery persisted in British Columbia even after that province joined Confederation and still has echoes today. And in other parts of the Americas, pre-contact, human sacrifice was practiced. It was of course colonialists — the British in Canada as only one example — who ended such practices.

How Indigenous identity politics imitate … Europe

Chopping up Canada into ever-more tribal enclaves is historically reminiscent of the continent often vilified in modern-day discourse: Europe. Both before the Roman Empire and after its collapse into the medieval age and until at least 1945 in various forms, the innate tribalism of Europe has long been costly in blood and treasure.

Mid-20th century historian Will Durant described the after-effects of the collapse of that empire and how Europe retreated into today what we could call “balkanization”: “half-isolated economic units in the countryside,” “state revenues declined as commerce contracted and industry fell,” and “impoverished governments could no longer provide protection for life, property, and trade.”

Of course, most people in human history have endured what the philosopher Thomas Hobbes described as nasty, brutish and short lives precisely because human beings have, for much of our history, found reasons to divide from each other. They did so most often for less-than-ideal reasons and with even less ideal results. But unlike those under most empires (at one end of possible political organization) or tribes (at the other), what mostly began as a British colonial experiment and is now modern-day Canada increasingly gave rights and prosperity to a diverse set of peoples — all of us “settlers.”

Of those who wish to turn Canada into a thousand mini-fiefdoms, we ask the same question Pierre Trudeau asked during a speech to a Montreal crowd during the 1980 referendum on separation. After describing Canada’s virtues and also the interdependent world we live in, Trudeau challenged the separatist-isolationists this way: “These people in Quebec and in Canada want to split it up? They want to take it away from their children? They want to break it down? No! — that’s our answer!” to which the crowd roared their approval.

What about one Canada for all?

The mostly peaceful northern country of Canada was not an accident but a conscious creation, mostly of the British, after their win on the Plains of Abraham in 1759 (with Indigenous allies, it should be noted). That led to the eventual victory of the British in 1763 and Canada’s eventual creation as a nation-state in 1867. Its success over centuries, pre- and post-Confederation, but especially in the postwar world, is also due to 19th-century British presumptions which fully flowered in the last century. That included expanded freedoms for all, including in 1960 when Indigenous Canadians were rightfully restored the right to vote.

Canada’s accomplishments include individual rights, including equality before the law and in policy (with the noted exception of reverse discrimination and DEI); legal protection of property rights (albeit not constitutionalized), a mostly open, free economy; the rule of law and independent courts; and democratic rule, among other achievements rare in human history.

There are thus two questions every Canadian today should ask.

First, was the arrival of later settlers, be they French or British in the 16th and 17th centuries and beyond, and later arrivals from Africa and Asia, mostly a positive development? We would argue that the answer is “yes” for all the above-noted reasons: Increasing freedoms for all over time, more prosperity, and peace on the northern half of the North American continent.

Second, the most fundamentally important question we can ask of each other in 2025 is not “When did your ancestors arrive here?” but “What kind of Canada do we want in the future?” Little good and much harm will come from destroying our inheritance, including private property, or ramping up identity politics which comes at the expense of equality of the individual, or continuing down the path of balkanization.

The better future for Canada is one where all are treated as equal in law and policy as much as practically possible. It is one where property rights are secure and the economy thrives, and where the “fusion” of peoples from all over the world continues what the first settlers began 20,000 years ago: A near-miraculous project where Canada is renewed to be a free, flourishing country where all are welcome.

Mark Milke is the president of the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. Tom Flanagan is a senior fellow at the Aristotle Foundation. Photo credit: iStock.

Aristotle Foundation

B.C. government laid groundwork for turning private property into Aboriginal land

It claims to oppose the Cowichan decision that threatens private property, but it’s been working against property owners for years

A City of Richmond letter to property owners in the Cowichan Aboriginal title area recognized by the B.C. Supreme Court has brought the judgment’s potential impacts into stark reality.

“For those whose property is in the area outlined in black,” the letter explained, “the Court has declared Aboriginal title to your property which may compromise the status and validity of your ownership.”

While Premier David Eby has been quick to disavow the decision, the reality is his government helped set the stage for it in multiple ways. Worse, it quietly supported a similar outcome in a related case, even after the concerning implications of the Cowichan judgment were well-known.

The problematic nature of the Cowichan decision has been well-established. It marks the first time a court has declared Aboriginal title over private property in B.C., and declares certain fee simple land titles (i.e., private property) in the area “defective and invalid.”

Understandably, the letter raised alarm bells not only for directly-affected property owners, but also for British Columbians generally, who recognize that the court’s findings in Richmond may well be replicated in other areas of the province in the future.

As constitutional law professor Dwight Newman pointed out in August, if past fee simple grants in areas of Aboriginal title claims are inherently invalid, “then the judgment has a much broader implication that any privately owned lands in B.C. may be subject to being overridden by Aboriginal title.”

In response to media questions about the City of Richmond’s letter, Eby re-stated his previous commitment to appeal the decision, saying, “I want the court to look in the eyes … of the people who will be directly affected by this decision, and understand the impact on certainty for business, for prosperity and for our negotiations with Indigenous people.”

While the words were the right ones, his government helped lay the groundwork for this decision in at least three ways.

First, the province set the policy precedent for the recognition of Aboriginal title over private property with its controversial Haida agreement in 2024. The legislation implementing the agreement was specifically referenced by the plaintiffs in the Cowichan case, and the judge agreed that it illustrated how Aboriginal title and fee simple can “coexist.”

Eby called the Haida agreement a “template” for other areas of B.C., despite the fact that it raised a number of democratic red flags, as well as legal concerns about private property rights and the constraints it places on the ability of future governments to act in the public interest.

While the agreement contains assurances that private property will be honoured by the Haida Nation, private property interests and the implementation of Aboriginal title are ultimately at odds. As Aboriginal law experts Thomas Isaac and Mackenzie Hayden explained in 2024, “The rights in land which flow from both a fee simple interest and Aboriginal title interest … include exclusive rights to use, occupy and manage lands. The two interests are fundamentally irreconcilable over the same piece of land.”

Second, the provincial and federal lawyers involved in the Cowichan proceedings were constrained by the government in terms of the arguments they were allowed to make to protect private property. In August, legal expert Robin Junger wrote, “One of the most important issues in this case was whether Aboriginal title was ‘extinguished’ when the private ownership was created over the lands by the government in the 1800s.”

The Cowichan judgment expressly notes that B.C. and Canada did not argue extinguishment. In B.C.’s case, this was due to civil litigation directives issued by Eby when he was attorney general.

Finally, provincial legislation implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) also played a role in supporting the judge’s conclusions, a point Newman wrote about in August. “They’re used in support of (even if not as the main argument for) the idea that Aboriginal title could yet take priority over current private property rights,”

In addition to setting the stage for the Cowichan decision, and despite their stated concerns with that judgment, the B.C. government has actively sought judicial recognition of Aboriginal title over private property elsewhere.

The overlaying of Aboriginal title over private property with the Haida agreement was already problematic enough prior to the Cowichan decision. However, even after the serious implications of the Cowichan decision were clear, the provincial and federal governments quietly went before the B.C. Supreme Court in support of a consent order that would judicially recognize the Aboriginal title over the entirety of Haida Gwaii.

The successful application had the effect of constitutionally entrenching Aboriginal title for the Haida Nation, including over private property, with the explicitly stated goal of making it near-impossible for future democratically elected governments to amend the agreement.

The reality is, the B.C. government claims to oppose the Cowichan decision even as it laid the groundwork for it, and it has actively pursued similar outcomes on Haida Gwaii. Repeated claims of seeking certainty and protecting private property have been belied by this government’s actions again and again.

Caroline Elliott, PhD, is a senior fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy and sits on the board of B.C.’s Public Land Use Society.

-

Alberta1 hour ago

Alberta1 hour agoFrom Underdog to Top Broodmare

-

Agriculture2 days ago

Agriculture2 days agoHealth Canada indefinitely pauses plan to sell unlabeled cloned meat after massive public backlash

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoAmerica first at the national parks: Trump hits Canadians and other foreign visitors with $100 fee

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoMexico’s Constitutional Crisis

-

Energy23 hours ago

Energy23 hours agoPoilievre says West Coast Pipeline MOU is no guarantee

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoB.C.’s First Money-Laundering Sentence in a Decade Exposes Gaps in Global Hub for Chinese Drug Cash

-

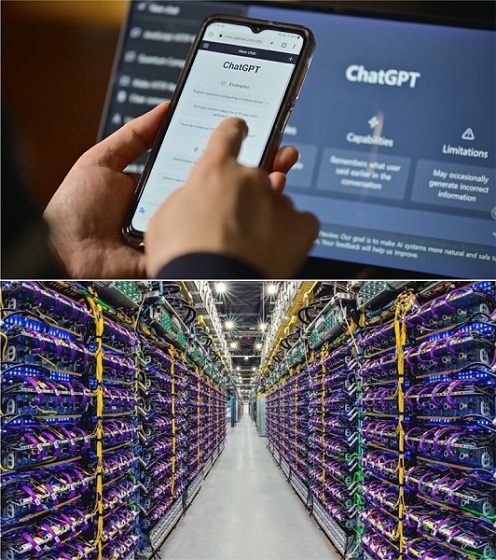

Artificial Intelligence2 days ago

Artificial Intelligence2 days agoTrump’s New AI Focused ‘Manhattan Project’ Adds Pressure To Grid

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoAfghan Ex–CIA Partner Accused in D.C. National Guard Ambush