Addictions

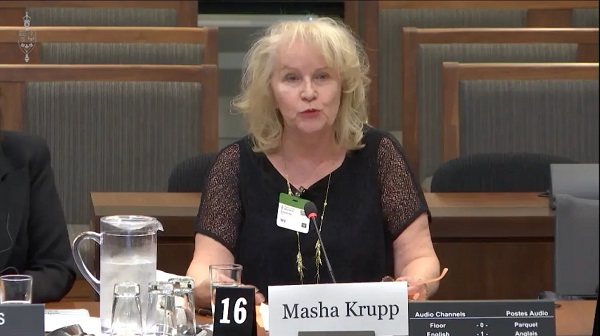

‘Our Liberal Government Is Acting Like A Drug Lord’: A Mother’s Testimony

By Adam Zivo

“As soon as [my son] was put on safe supply, he started diverting his safe supply” Mom tells Parliament safer supply isn’t working

“The whole purpose of the safer supply program was to divert addicts from using harmful street drugs, but that’s not happening,” testified Masha Krupp, an Ottawa-based mother, at the House of Commons Health Committee last week. Exhausted and blunt, she described how her son has, in the past, diverted his “safer supply” drugs to the black market and how she has personally witnessed widespread diversion, by other patients, outside the clinic her son attends.

Safer supply programs distribute free addictive drugs – typically hydromorphone, a heroin-strength opioid – under the belief that this stabilizes addicts and dissuades them from consuming riskier street substances. Addiction experts and police leaders across Canada, however, say that recipients regularly divert these taxpayer-funded drugs to the black market, fueling new addictions and gang profits.

The Liberals and NDP have denied that widespread safer supply diversion is occurring, despite ample evidence to the contrary – but Krupp’s lived experiences underline the folly of their willful blindness.

“As soon as he was put on safe supply, he started diverting his safe supply,” she testified. “You’ve got drug dealers – I know this for a fact through my son; I’ve seen it – they will come to your home, 24/7, you can call two in the morning. They take your hydromorphone pills.”

According to Krupp, her son’s addiction issues have not improved despite him being enrolled in a safer supply program for more than two years. He still uses fentanyl and crack cocaine, which led to yet another overdose just last month, she said, adding that diversion and a lack of recovery-oriented services contribute to his instability.

“The Dilaudid (brand name hydromorphone) is a means of currency for my son to continue using crack cocaine – so it’s not safe, because he’s still using unsafe street drugs,” she said in parliament.

Krupp further explained that, on multiple occasions, she witnessed and photographed patients selling their safer supply in front of the clinic where her son has been a patient since June 2021. The transactions were not subtle: she could see them counting and exchanging white pills.

Over time, Krupp corroborated these observations by acquainting herself with some of these patients, who would admit to selling their safer supply: “I get to know all these people that are diverting and using right in front of the clinic, in front of all the tourists, parents walking by with kids.”

She believes that safer supply could have a role in addiction care if it were better regulated, but feels that the current model, where supervised consumption of these drugs is rarely required, is only “flooding the market, using taxpayers’ dollars, with lethal opiates…”

“It’s unsafe supply, in my view, as a mother with lived experience,” said Krupp. “Our Liberal government, right now, is acting like a drug lord.”

Her testimony was consistent with what was described in a CBC investigative report published last February, wherein Ottawa’s police officers confirmed that safer supply diversion is rampant.

One constable quoted in the story, Paul Stam, said that virtually anytime police would pull up to Rideau and Nelson street, where the clinic Krupp’s son attends is located, “they would observe people openly trafficking in diverted hydromorphone.” The officer further told the CBC that the “street is flooded with this pharmaceutical grade hydromorphone” and that there has been a dramatic, province-wide reduction in the drug’s blackmarket price – from $8-9 per 8-mg pill to just $1-2 today.

Although Krupp gave her parliamentary testimony last week, I interviewed her in July and kept her story private at her request – at the time, she worried that going public could interfere with her son’s attempts at recovery.

In the July interview, Krupp explained that, not only had her son told her that safer supply diversion is ubiquitous, she had also heard this from two acquaintances of his, who were also on the program: “The information that I’ve received is that the drug dealers have operations set up 24/7 across the city, buying legal dillies (the slang term for hydromorphone).”

She explained that she had been able to witness and document safer supply diversion because, on most Friday mornings, she would take her son to his clinic appointments and wait for him outside in her car. As she was often parked just two or three metres away from where many drug deals occurred, she had a line of sight into what was going on: clearly-identifiable dillies being handed over for other drugs.

She estimated that, by that point, she had cumulatively witnessed at least 25 safer supply patients engage in diversion.

“[Safer supply patients] would trade their dillies for fentanyl and/or crack cocaine and smoke or inject it right in front of me. They would just huddle in a corner. It’s all done very openly,” she said. “What I witness, to me, is a human tragedy on the sidewalks of the nation’s capital, with Parliament Hill eight or nine blocks away, and all the politicians sitting there singing praises to safer supply.”

She pushed back on the narrative, popular among Liberal and NDP politicians, that criticism of safer supply is conservative fear mongering and said that she had voted NDP in the past, and had even voted for Trudeau in 2015. Her disgust with safer supply was simply her “speaking from the heart as a mother.”

While harm reduction activists claim that safer supply is a form of compassionate care, Krupp vehemently disagreed: “How is it compassionate to fuel somebody’s addiction? How is it humane to keep a perpetual cycle of drug abuse and dependence?”

Subscribe to Break The Needle. Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

Addiction experts demand witnessed dosing guidelines after pharmacy scam exposed

By Alexandra Keeler

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

An addiction medicine advocacy group is urging B.C. to promptly issue new guidelines for witnessed dosing of drugs dispensed under the province’s controversial safer supply program.

In a March 24 letter to B.C.’s health minister, Addiction Medicine Canada criticized the BC Centre on Substance Use for dragging its feet on delivering the guidelines and downplaying the harms of prescription opioids.

The centre, a government-funded research hub, was tasked by the B.C. government with developing the guidelines after B.C. pledged in February to return to witnessed dosing. The government’s promise followed revelations that many B.C. pharmacies were exploiting rules permitting patients to take safer supply opioids home with them, leading to abuse of the program.

“I think this is just a delay,” said Dr. Jenny Melamed, a Surrey-based family physician and addiction specialist who signed the Addiction Medicine Canada letter. But she urged the centre to act promptly to release new guidelines.

“We’re doing harm and we cannot just leave people where they are.”

Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter also includes recommendations for moving clients off addictive opioids altogether.

“We should go back to evidence-based medicine, where we have medications that work for people in addiction,” said Melamed.

‘Best for patients’

On Feb. 19, the B.C. government said it would return to a witnessed dosing model. This model — which had been in place prior to the pandemic — will require safer supply participants to take prescribed opioids under the supervision of health-care professionals.

The move follows explosive revelations that more than 60 B.C. pharmacies were allegedly participating in a scheme to overbill the government under its safer supply program. The scheme involved pharmacies incentivizing clients to fill prescriptions they did not require by offering them cash or rewards. Some of those clients then sold the drugs on the black market.

In its Feb. 19 announcement, the province said new participants in the safer supply program would immediately be subject to the witnessed dosing requirement. For existing clients of the program, new guidelines would be forthcoming.

“The Ministry will work with the BC Centre on Substance Use to rapidly develop clinical guidelines to support prescribers that also takes into account what’s best for patients and their safety,” Kendra Wong, a spokesperson for B.C.’s health ministry, told Canadian Affairs in an emailed statement on Feb. 27.

More than a month later, addiction specialists are still waiting.

According to Addiction Medicine Canada’s letter, the BC Centre on Substance Use posed “fundamental questions” to the B.C. government, potentially causing the delay.

“We’re stuck in a place where the government publicly has said it’s told BCCSU to make guidance, and BCCSU has said it’s waiting for government to tell them what to do,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

This lag has frustrated addiction specialists, who argue the lack of clear guidance is impeding the transition to witnessed dosing and jeopardizing patient care. They warn that permitting take-home drugs leads to more diversion onto the streets, putting individuals at greater risk.

“Diversion of prescribed alternatives expands the number of people using opioids, and dying from hydromorphone and fentanyl use,” reads the letter, which was also co-signed by Dr. Robert Cooper and Dr. Michael Lester. The doctors are founding board members of Addiction Medicine Canada, a nonprofit that advises on addiction medicine and advocates for research-based treatment options.

“We have had people come in [to our clinic] and say they’ve accessed hydromorphone on the street and now they would like us to continue [prescribing] it,” Melamed told Canadian Affairs.

A spokesperson for the BC Centre on Substance Use declined to comment, referring Canadian Affairs to the Ministry of Health. The ministry was unable to provide comment by the publication deadline.

Big challenges

Under the witnessed dosing model, doctors, nurses and pharmacists will oversee consumption of opioids such as hydromorphone, methadone and morphine in clinics or pharmacies.

The shift back to witnessed dosing will place significant demands on pharmacists and patients. In April 2024, an estimated 4,400 people participated in B.C.’s safer supply program.

Chris Chiew, vice president of pharmacy and health-care innovation at the pharmacy chain London Drugs, told Canadian Affairs that the chain’s pharmacists will supervise consumption in semi-private booths.

Nathan Wong, a B.C.-based pharmacist who left the profession in 2024, fears witnessed dosing will overwhelm already overburdened pharmacists, creating new barriers to care.

“One of the biggest challenges of the retail pharmacy model is that there is a tension between making commercial profit, and being able to spend the necessary time with the patient to do a good and thorough job,” he said.

“Pharmacists often feel rushed to check prescriptions, and may not have the time to perform detailed patient counselling.”

Others say the return to witnessed dosing could create serious challenges for individuals who do not live close to health-care providers.

Shelley Singer, a resident of Cowichan Bay, B.C., on Vancouver Island, says it was difficult to make multiple, daily visits to a pharmacy each day when her daughter was placed on witnessed dosing years ago.

“It was ridiculous,” said Singer, whose local pharmacy is a 15-minute drive from her home. As a retiree, she was able to drive her daughter to the pharmacy twice a day for her doses. But she worries about patients who do not have that kind of support.

“I don’t believe witnessed supply is the way to go,” said Singer, who credits safer supply with saving her daughter’s life.

Melamed notes that not all safer supply medications require witnessed dosing.

“Methadone is under witness dosing because you start low and go slow, and then it’s based on a contingency management program,” she said. “When the urine shows evidence of no other drug, when the person is stable, [they can] take it at home.”

She also noted that Suboxone, a daily medication that prevents opioid highs, reduces cravings and alleviates withdrawal, does not require strict supervision.

Kendra Wong, of the B.C. health ministry, told Canadian Affairs that long-acting medications such as methadone and buprenorphine could be reintroduced to help reduce the strain on health-care professionals and patients.

“There are medications available through the [safer supply] program that have to be taken less often than others — some as far apart as every two to three days,” said Wong.

“Clinicians may choose to transition patients to those medications so that they have to come in less regularly.”

Such an approach would align with Addiction Medicine Canada’s recommendations to the ministry.

The group says it supports supervised dosing of hydromorphone as a short-term solution to prevent diversion. But Melamed said the long-term goal of any addiction treatment program should be to reduce users’ reliance on opioids.

The group recommends combining safer supply hydromorphone with opioid agonist therapies. These therapies use controlled medications to reduce withdrawal symptoms, cravings and some of the risks associated with addiction.

They also recommend limiting unsupervised hydromorphone to a maximum of five 8 mg tablets a day — down from the 30 tablets currently permitted with take-home supplies. And they recommend that doses be tapered over time.

“This protocol is being used with success by clinicians in B.C. and elsewhere,” the letter says.

“Please ensure that the administrative delay of the implementation of your new policy is not used to continue to harm the public.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle

2025 Federal Election

Poilievre to invest in recovery, cut off federal funding for opioids and defund drug dens

From Conservative Party Communications

Poilievre will Make Recovery a Reality for 50,000 Canadians

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre pledged he will bring the hope that our vulnerable Canadians need by expanding drug recovery programs, creating 50,000 new opportunities for Canadians seeking freedom from addiction. At the same time, he will stop federal funding for opioids, defund federal drug dens, and ensure that any remaining sites do not operate within 500 meters of schools, daycares, playgrounds, parks and seniors’ homes, and comply with strict new oversight rules that focus on pathways to treatment.

More than 50,000 people have lost their lives to fentanyl since 2015—more Canadians than died in the Second World War. Poilievre pledged to open a path to recovery while cracking down on the radical Liberal experiment with free access to illegal drugs that has made the crisis worse and brought disorder to local communities.

Specifically, Poilievre will:

- Fund treatment for 50,000 Canadians. A new Conservative government will fund treatment for 50,000 Canadians in treatment centres with a proven record of success at getting people off drugs. This includes successful models like the Bruce Oake Recovery Centre, which helps people recover and reunite with their families, communities, and culture. To ensure the best outcomes, funding will follow results. Where spaces in good treatment programs exist, we will use them, and where they need to expand, these funds will allow that.

- Ban drug dens from being located within 500 metres of schools, daycares, playgrounds, parks, and seniors’ homes and impose strict new oversight rules. Poilievre also pledged to crack down on the Liberals’ reckless experiments with free access to illegal drugs that allow provinces to operate drug sites with no oversight, while pausing any new federal exemptions until evidence justifies they support recovery. Existing federal sites will be required to operate away from residential communities and places where families and children frequent and will now also have to focus on connecting users with treatment, meet stricter regulatory standards or be shut down. He will also end the exemption for fly-by-night provincially-regulated sites.

“After the Lost Liberal Decade, Canada’s addiction crisis has spiralled out of control,” said Poilievre. “Families have been torn apart while children have to witness open drug use and walk through dangerous encampments to get to school. Canadians deserve better than the endless Liberal cycle of crime, despair, and death.”

Since the Liberals were first elected in 2015, our once-safe communities have become sordid and disordered, while more and more Canadians have been lost to the dangerous drugs the Liberals have flooded into our streets. In British Columbia, where the Liberals decriminalized dangerous drugs like fentanyl and meth, drug overdose deaths increased by 200 percent.

The Liberals also pursued a radical experiment of taxpayer-funded hard drugs, which are often diverted and resold to children and other vulnerable Canadians. The Vancouver Police Department has said that roughly half of all hydromorphone seizures were diverted from this hard drugs program, while the Waterloo Regional Police Service and Niagara Regional Police Service said that hydromorphone seizures had exploded by 1,090% and 1,577%, respectively.

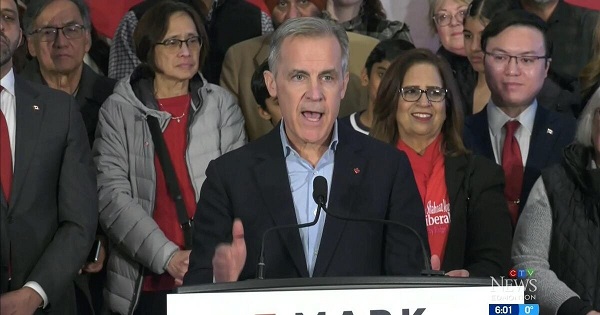

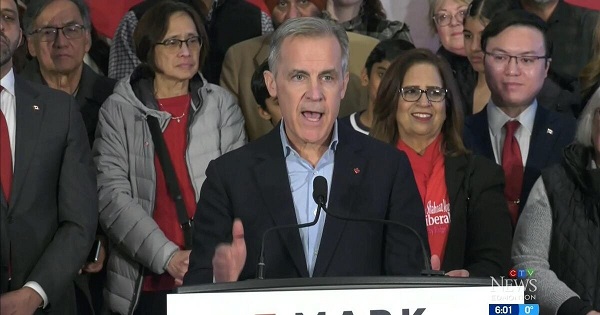

Despite the death and despair that is now common on our streets, bizarrely Mark Carney told a room of Liberal supporters that 50,000 fentanyl deaths in Canada is not “a crisis.” He also hand-picked a Liberal candidate who said the Liberals “would be smart to lean into drug decriminalization” and another who said “legalizing all drugs would be good for Canada.”

Carney’s star candidate Gregor Robertson, an early advocate of decriminalization and so-called safe supply, wanted drug dens imposed on communities without any consultation or public safety considerations. During his disastrous tenure as Vancouver Mayor, overdoses increased by 600%.

Alberta has pioneered an approach that offers real hope by adopting a recovery-focused model of care, leading to a nearly 40 percent reduction in drug-poisoning deaths since 2023—three times the decrease seen in British Columbia. However, we must also end the Liberal drug policies that have worsened the crisis and harmed countless lives and families.

To fund this policy, a Conservative government will stop federal funding for opioids, defund federal drug dens, and sue the opioid manufacturers and consulting companies who created this crisis in the first place.

“Canadians deserve better than the Liberal cycle of crime, despair, and death,” said Poilievre. “We will treat addiction with compassion and accountability—not with more taxpayer-funded poison. We will turn hurt into hope by shutting down drug dens, restoring order in our communities, funding real recovery, and bringing our loved ones home drug-free.”

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoPope Francis has died aged 88

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoPope Francis Dies on Day after Easter

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoJD Vance was one of the last people to meet Pope Francis

-

2025 Federal Election18 hours ago

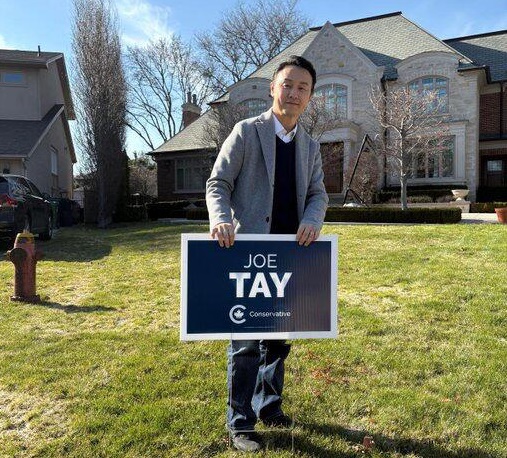

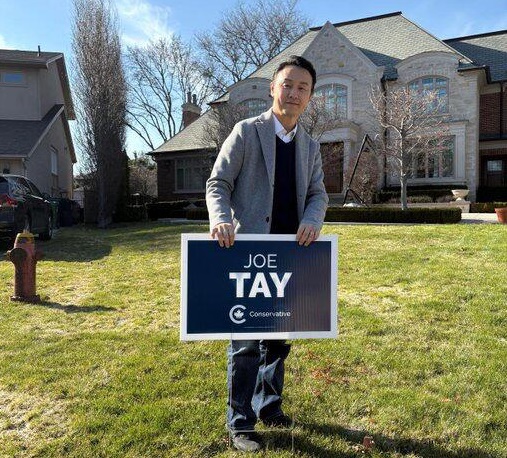

2025 Federal Election18 hours agoOttawa Confirms China interfering with 2025 federal election: Beijing Seeks to Block Joe Tay’s Election

-

2025 Federal Election17 hours ago

2025 Federal Election17 hours agoHow Canada’s Mainstream Media Lost the Public Trust

-

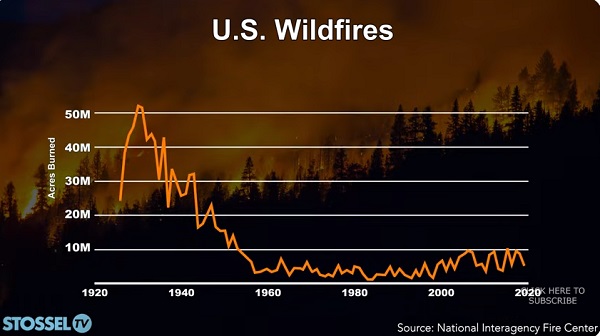

John Stossel10 hours ago

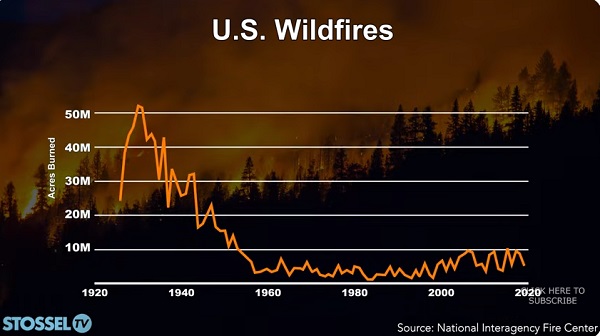

John Stossel10 hours agoClimate Change Myths Part 2: Wildfires, Drought, Rising Sea Level, and Coral Reefs

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada Urgently Needs A Watchdog For Government Waste

-

2025 Federal Election7 hours ago

2025 Federal Election7 hours agoCHINESE ELECTION THREAT WARNING: Conservative Candidate Joe Tay Paused Public Campaign